D-Lib Magazine

May/June 2017

Volume 23, Number 5/6

Table of Contents

The Digital Public Library of America and the National Digital Platform

Emily Gore, Michael Della Bitta and Dan Cohen

Digital Public Library of America

{emily, michael, dan} [at] dp.la

https://doi.org/10.1045/may2017-gore

Abstract

The Digital Public Library of America brings together the riches of America's libraries, archives, and museums, and makes them freely available to the world. In order to do this, DPLA has had to build elements of the national digital platform to connect to those institutions and to serve their digitized materials to audiences. In this article, we detail the construction of two critical elements of our work: the decentralized national network of "hubs," which operate in states across the country; and a version of the Hydra repository software that is tailored to the needs of our community. This technology and the organizations that make use of it serve as the foundation of the future of DPLA and other projects that seek to take advantage of the national digital platform.

Keywords: Digital Public Library of America, DPLA, National Digital Platform

1 Introduction

The Digital Public Library of America launched in April 2013 with the goal of maximizing access to our shared culture. Although numerous digitization efforts began early in the history of the web, in the mid-1990s, and have continued to the present day, there was not much coordination between these efforts and no easy, unified way to find what was available. Furthermore, there are types of materials, such as ebooks and audiovisual works, that have structural issues to access due to copyright, technology, or other issues.

DPLA was founded to solve these problems and to increase access as much as possible. Currently, the Digital Public Library of America holds over 15 million items from over 2,000 libraries, archives, and museums in the United States. When we launched in April of 2013, we had only 2.4 million items from approximately 500 institutions. While we are proud of this rapid and significant growth, we still have thousands of institutions that would like to join DPLA, and likely hundreds of millions of items, ranging from digitized books, photographs, manuscripts, and maps, to audio and video, to paintings and sculpture, to works from all fields of the natural sciences. So in a sense we are still at just the beginning of an important, multi-decade effort.

Unlike single libraries, even those of great size, we do our work in a highly distributed way. We have what we call state-based "Service Hubs," and it is through those hubs that we are able to assemble a very large-scale virtual library. These hubs help us gather materials from across the country, ensure that there is good metadata about those materials, and store and serve the digital content to audiences from around the world.

In addition to this distributed model, we have more recently endeavored, through the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) funding and through a partnership with Stanford and DuraSpace, to provide a new digital infrastructure for our hubs that is robust and modern. Leveraging the Hydra Project, we have created Hyku, which can act as a turnkey solution for our hubs to host and to more seamlessly share their content with DPLA, and thus the world.

Our work therefore connects with the National Digital Platform in two main ways. First, it creates for the first time a highly networked digital library system that unites and makes maximally available the content from thousands of institutions; and second, it uses cutting-edge technology to serve that material in contemporary, advanced ways.

2 The National Network of Hubs

DPLA would not exist without the collaboration of our Content Hubs and Service Hubs, the organizations that both aggregate metadata from their partners — the library, museum, archive, and cultural heritage institutions from across the US — and then contribute it to DPLA. Combined, these institutions bring together millions of records about digital texts, photographs, manuscript materials, artwork, and more, available for use through the DPLA portal and application programming interface (API).

Content Hubs are large institutions, like the National Archives or The Library of Congress, that work with DPLA to share cultural heritage data on a one-to-one basis through a single data feed. Service Hubs, in contrast, work to share data with DPLA on a one-to-many basis through a single feed. Service Hubs, currently geographically focused, represent cultural heritage institutions in a single state or region of the country.

When launching DPLA, we worked with a number of states who had existing statewide digital collections, including the Digital Library of Georgia and the Minnesota Digital Library. Through participation in DPLA, both Georgia and Minnesota have been able to significantly expand their collections and the number of institutions that participate in their statewide effort. In 2013, when Minnesota joined DPLA as one of the initial Service Hubs, 175 cultural heritage organizations, largely small libraries, archives, museums and historical societies, contributed 46,000 records from a centralized database. Since that time, Minnesota has added an aggregation layer, which includes the digital collections of seven large institutions, and they now contribute over 500,000 items to DPLA.

Other Service Hubs, like the Empire State Digital Network (which as the name suggests covers New York), were not pre-existing, and were instead formed with the goal of sharing content with DPLA. New York had a number of collaborative digital cultural heritage projects, but not one that had statewide coverage. The Empire State Digital Network, administered by The Metropolitan New York Library Council (METRO), now has over 200 partners and contributes over 350,000 items to DPLA.

At launch, DPLA represented a collaborative of eighteen Content and Service Hubs, who together provided free and open access to 2.4 million digital objects. As of March 2017, DPLA is a collaborative of forty-five Content and Service Hubs, providing access to over 15.5 digital objects and is growing regularly. Within the next two years, we hope to complete the national network by having an on-ramp to DPLA in every state in the country. At that time, we will work to improve collection gaps and seek targeted content in order to round out the network.

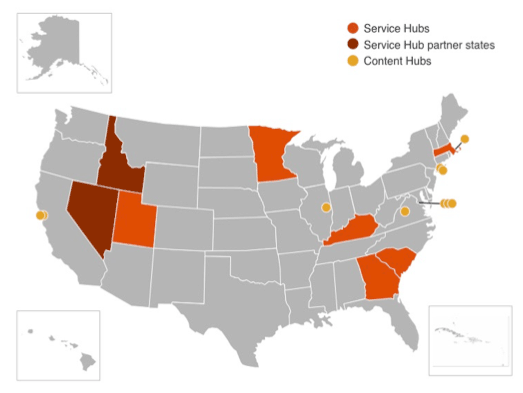

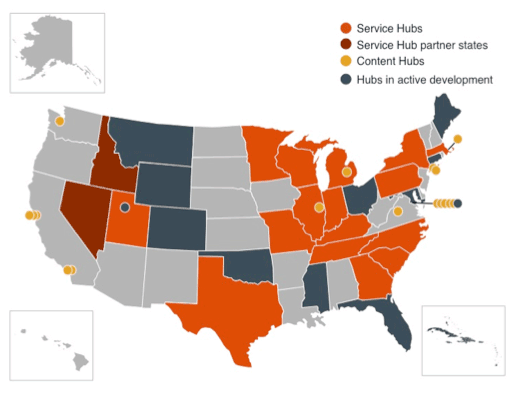

Figure 1 below shows the locations of hub participants at the launch of the Digital Public Library of America website in April of 2013. Figure 2, by contrast, shows the current status of hub participants and highlights the growth of the network over the past four years.

Figure 1: DPLA Hub locations, April 2013

Figure 2: DPLA Hub locations, March 2017

3 Digital Infrastructure

When DPLA was first conceived, there was no stream of digital items ready and waiting. The first task was to build out the network of hubs that would together provide this stream of the nation's cultural heritage. Since most of these hub organizations were yet to be founded, an early strategy to scale DPLA's network involved meeting hubs where they already were in terms of technology and metadata, rather than dictate that the hubs provide data in a specific format via a specific channel.

As a result, the digital infrastructure of DPLA and constituent hubs is highly heterogeneous. On a regular basis, DPLA consumes metadata via diverse channels including OAI-PMH, bespoke APIs, and data dumps. This data arrives in a variety of formats, typically JSON or XML, that can correspond to numerous schemas and interpretations thereof. And the systems providing this data range from open source, off the shelf software, to proprietary services, to software custom-built for the purpose of participating in DPLA. No two DPLA hubs are alike.

Even with this polyglot take on metadata aggregation, DPLA does encounter providers that do not have the technological resources available to easily participate in the hubs network. Our hubs and providers have diverse quantities of funding and personnel, and the task of maintaining the niche infrastructure and technological know-how to participate in DPLA can be costly and time-consuming. Even well-resourced hubs have potential providers of their own who hold amazing items in their collection but lack the resources to share them digitally.

A solution that made it simple for these partners to contribute their collections to DPLA by providing them with the tools to record, preserve, and syndicate their metadata would be of utmost use. DPLA, along with partner organizations DuraSpace and Stanford University, banded together to develop a plan to satisfy this need.

Thanks to a generous grant from the IMLS, DPLA and its partners have embarked on a multi-pronged project to create a robust application for next-generation digital asset management. A core pillar of this project is to devote significant effort toward enhancing Hydra, which brings together several important platforms to form a coherent but flexible repository solution.

Hydra's architecture is based on the availability of several key components, including Fedora Commons Repository for data preservation, Apache Solr for full-text indexing of repository content, Blacklight for search and discovery, Hydra-Head, a Ruby on Rails Engine for primary content management operations, and numerous Ruby gems to provide a variety of additional end-user interfaces and workflows.

However, because Hydra was never meant to be a one-size-fits-all solution for digital repositories, but rather an extensible and reconfigurable constellation of components, uptake can be daunting for new users, and turnkey installs were never meant as a deliverable for the general Hydra project.

Enter the Hydra-In-A-Box project. This effort strives to produce a polished, feature-complete, easy-to-install and maintain, turnkey Hydra-based application for next-generation digital asset management. This is being accomplished by standardizing and combining some components in the Hydra infrastructure into a unified release that is easy to install and highly cohesive. The main output of the Hydra-In-A-Box project has recently been named Hyku.

Another chief aim of this effort is to offer Hyku as a hosted service named HykuDirect. A customer of this service would be given access to a competitively-priced instance of the Hyku application in the cloud that will be fully managed and maintained by DuraSpace, which hopes to offer HykuDirect service after a pilot period to occur in 2017. Onboarding new institutions would be as simple as registering for any common software-as-a-service product, and costs would be minimized by economies of scale realized by hosting multiple customers in the same infrastructure. To avoid vendor lock-in, Hyku's codebase will remain entirely open source and freely available, and migrations of content to and from this service will remain unfettered. The Hyrda-In-A-Box partners are holding conversations with other potential service vendors who could offer Hyku as a service as well. Ideally, a potential customer will be able to choose from several vendors who in turn might tailor their services to specific markets or use cases.

DPLA sees immense potential for a federation of data providers armed with Hyku. ResourceSync, the new metadata syndication format conceived as a replacement to OAI-PMH, will be baked in, which means that parallel harvests and incremental updates are available out of the box. And the Hyku team has committed to producing exports in DPLA's Metadata Application Profile, which will greatly reduce the friction in bringing in new providers to DPLA's platform. Finally, Hyku features built-in IIIF (International Image Interoperability Framework) support, which will offer providers a great way to allow users to see zoomable, full resolution views of their content no matter where users encounter it on the Internet.

These advances will help our hubs harvest their providers as well, but potentially most important is the fact that they promote a national network of content access, aggregation, and analytics. DPLA hopes that the Hyku product will produce a vibrant, participatory community of adopters and contributors.

Alongside participating in work on Hyku, DPLA has engaged in ongoing work to improve and generalize DPLA's metadata aggregation tools into more reusable components. DPLA's aim is that the result of this work is generally useful for metadata aggregation, enrichment, analysis, and publishing.

4 Conclusion

DPLA's quickly growing national network of hubs and the new technologies we are working on with partners will directly and greatly contribute to the dream of a national digital platform. It has been exciting to see that platform develop, and to make large-scale contributions to it. DPLA's open and extensible structure was always envisioned as a critical and helpful part of the knowledge ecosystem in the United States and beyond. The millions of items we serve to millions of students, teachers, researchers, and members of the general public every year are a testament to the strength of that model and the progress that has been made thus far.

About the Authors

Emily Gore is the Director of Content for the Digital Public Library of America, a position she has held since the inception of DPLA. Gore's 17 year career in libraries has focused largely on digital cultural heritage collaboration.

Michael Della Bitta is Director of Technology at DPLA. Michael has worked in software development and publications and in the startup, library, and education spaces for nearly twenty years.

Dan Cohen is the founding Executive Director of the Digital Public Library of America. A historian by training, he has worked on large-scale digital projects to increase access and expand research opportunities.