|

D-Lib Magazine

November/December 2012

Volume 18, Number 11/12

Table of Contents

Viewshare and the Kress Collection: Creating, Sharing, and Rapidly Prototyping Visual Interfaces to Cultural Heritage Collection Data

Lauren Algee, National Gallery of Art

l-algee@nga.gov

Jefferson Bailey, Metropolitan New York Library Council

jbailey@metro.org

Trevor Owens, Library of Congress

trow@loc.gov

doi:10.1045/november2012-algee

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

Visualization tools for digital cultural heritage collections allow users to discover connections between artifacts over time and across space. Created using curators' and collection stewards' unique knowledge of their collections, visualizations empower users to discover meaning and patterns within digital collections using dynamic, interactive displays. Viewshare, a free, open-source visualization platform developed by the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program at the Library of Congress and its partners, is such a tool. Viewshare's primary function is as a platform for generating and customizing views that enable users to creatively experience digital cultural heritage collections. But Viewshare can also be used by institutions as a testbed for development of web requirements and as a step in the larger workflow of managing collection data and testing its potential augmentation and exhibition. This article explains the conceptual framework behind Viewshare's development and its specific functions and affordances. The article then explicates a specific, detailed use case of Viewshare by the National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives, demonstrating both how Viewshare offers a new way for collection managers and users to understand collections and also how Viewshare can serve as a rapid prototyping tool by which content managers can refine their existing practices around digital collection management, description, and display.

Introduction

Empowering users has long been a goal of digital collection stewards. Supporting discovery, use, and navigation of digital collections is a fundamental part of providing access and encouraging inquiry, interpretation, and knowledge. Digital collections, however, are dependent upon the interfaces through which they are explored and those interfaces do not necessarily encourage the modes of discovery that can provide new insights. As data analysis and computational tools become more common and more familiar to users, digital collection managers will need to ask whether traditional interfaces truly support the increasingly novel and exploratory ways that users engage with online collections. For cultural heritage institutions, digital collections are often built around the same path-based information-seeking behaviors that characterize online public access library catalogs. If you want a specific item, those catalogs are powerful tools by which to narrowly refine your query within the extensive bibliographic data associated with individual resources. But such directed searching often fails to complement the ability to iteratively explore, compare data trends, and engender the accidental wisdom that comes from visualizing collections in new ways. We have the tools to build and create visual interfaces that allow for exploration: navigating collections on maps, charting relationships between information in collections, and navigating through a range of faceted browsing techniques. With this said, it is both cumbersome to develop these kinds of interfaces and it is difficult to know exactly what will be valuable once presented within them. Viewshare, a tool developed by the Library of Congress, offers some interesting aid in both of these respects.

Consideration of Visualization Product and Process

Viewshare is a free, open software platform developed by the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program (NDIIPP) of the Library of Congress that enables collection managers and users to create new ways of seeing and navigating digital collections. Viewshare was originally developed to provide access to digital collections selected for preservation as part of NDIIPP through a shared interface. Once it became evident how the tool could accentuate the use and understanding of a diverse range of digital content from disparate repositories, it was clear the software would be of value to the broader cultural heritage community. Viewshare's primary function is as a platform for generating and customizing views that allow users to dynamically and creatively experience digital collections. We have written about the value of developing and sharing these interfaces to collections elsewhere (Bailey & Owens, 2012); in this essay we hope to explore more deeply an emergent use case for the tool that we think demonstrates its unique benefits.

As the development of the platform progressed, we saw an interesting trend in our own use of Viewshare as well as how our test account users were working with the tool. The process of rapidly creating these interfaces turned out to be more valuable in many cases than the final product of the views. The tool is first and foremost a platform for prototyping interfaces and thinking about cultural heritage collection data. For many users, the interfaces created with the tool are useful ends in and of themselves. Particularly at smaller institutions, or for smaller collections, we see Viewshare as a platform for providing more sophisticated modes of access to collection content. However, at larger organizations we have seen the tool serving as a stepping-stone toward developing larger cultural heritage projects for online collections. Instead of wireframing an expansive, costly collection portal, it is possible to, in a matter of minutes, create an interface to a collection and uncover both the limitations of a collection dataset and also potential ways to enhance its presentation.

Viewshare's ability to expose the possibilities and limitations of a collection as a dataset is a function of its design, which recognizes a number of emerging technical and intellectual trends in the cultural heritage community. Viewshare acknowledges the heterogeneity of metadata types across a diverse group of repositories and thus supports a variety of collection ingest methods. Viewshare also adheres to linked open data principles by making the metadata that powers its interfaces open and exportable in a variety of formats. Viewshare's own code, being open-source, is also available for download and re-use. By prioritizing the openness of data, it provides an easy means of data ingest and facilitates quick and easy experimentation with visualizations and interfaces. Viewshare's open data principles also allow multiple users to create different views off of the same collection dataset. Viewshare also allows sharing of collection views through links, encouraging collaboration and group prototyping; the interfaces created using the software can also be embedded in third-party websites. The platform features a drag-and-drop view-building workspace and multiple preview options that allow users to test and refine their views prior to making them public. Most importantly, by allowing content stewards to create new visual interfaces to their collections, it capitalizes on the affordances of richly cataloged items and situates them in the nexus of an overall collection. The unique and detailed contextual knowledge of collection managers is accentuated by Viewshare's features — features that allow those managers to present digital collections as a corpora, an interconnected set of items sharing significant, meaningful properties, by creating dynamic interfaces that form a bridge between their curatorial understanding and users' exploratory, generative behavior.

This paper is a collaborative effort between two of the project's staff at the Library of Congress, Jefferson Bailey and Trevor Owens, and one of the users, Lauren Algee, Project Archivist for the Samuel H. Kress Collection Database at the The National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives. Lauren developed a view that we think exemplifies some of the most valuable cases for using the tool. After providing some context for the idea behind the Viewshare platform, we describe how Lauren came to work with the tool, what she used it for, and an explication of the value it provided her in her ongoing work on the Samuel H. Kress Collection Database project. Our goal in presenting this essay is to provide an introduction to the tool, demonstrate its powerful visualization features, and offer a specific worked example of how it can fit into the workflow of a large project at a cultural heritage institution.

From Visualizations to Revelations

Visualizations offer a framing device, an interpretation of how both curators and users can think about and understand a collection of materials (Staley, 2003). Visualization allows users to ask new questions and explore the connections between artifacts over time and across space; it is also increasingly being understood not only as a means to provide access, but also as a potential mode of scholarly inquiry. Visualization can be thought of as part of a hermeneutic research process — a process that is "generative and iterative, capable of producing new knowledge through the aesthetic provocation" (Jessop, 2008; Drucker, 2010). In this respect, visualizations function as tools for a distant reading that focuses on the development of aggregate abstractions of information from objects which can help to warrant and provoke novel interpretations (Moretti, 2005). In short, the development of an interface to a collection is itself an interpretive act which surfaces particular pathways for exploration and interpretation by end users. At its heart, Viewshare aims to empower both the end user and the librarian, archivist, curator or scholar creating the interface to undertake, a "highly serendipitous journey replacing the ordered mannerism of conventional search" (Ramsey, forthcoming). This view of visualization from the humanities also has significant resonances with emerging approaches to visualization tools more broadly. As Heer and Sinderman suggest in their recent development of a "taxonomy of tools that support the fluent and flexible use of visualizations," visualization "typically progresses in an iterative process of view creation, exploration, and refinement." Importantly, from their perspective, "meaningful analysis consists of repeated explorations as users develop insights about significant relationships, domain-specific contextual influences, and causal patterns" (2012). In short, there is an emerging consensus of the value of tools that support this kind of exploratory process from a range of disciplinary perspectives.

Those intellectual foundations are meaningless without building a tool designed for broad, easy use by a community with a wide range of technical skills. Bridging the ideals of open data, serendipitous discovery, and the didactic power of data visualization with a functional tool that is easy to use has been the fundamental challenge in building the Viewshare platform. In developing Viewshare the goal remains to create an application that is open, beneficial, and widely adopted. Viewshare was also designed to provide collection managers without deep technical skills an intuitive way to articulate and expose their significant knowledge of the digital collections they manage. It needed to balance the complex demands of being "sophisticated, robust, transparent, and easy to use" in order to attract a broad user base (Borgman, 2009). Software tools, especially in the cultural heritage community, need to promote, encourage, and support an interpretive provocation. They need to empower both collection stewards and collection patrons to explore and understand, support both conventional curation activities as well as interactivity, be easy to use, and encourage both close and distant reading, and facilitate iteration and demonstration (Gibbs & Owens, 2012).

The Kress Collection as a Viewshare Use Case

Funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, the Samuel H. Kress History and Conservation Database Project began at the National Gallery of Art's Gallery Archives in 2009 with the goal of creating a relational database to hold information on the development and dispersal of the Samuel H. Kress Collection. Beginning in the 1920s, department store magnate Samuel H. Kress, his brother Rush, and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation spent nearly three decades amassing and giving away over 3,600 paintings, sculptures, medals, and decorative art, primarily focusing on works from the Italian Renaissance. The largest segment of the collection was donated to the National Gallery. Kress works comprised three-quarters of the works on display at the Gallery's opening in 1941 (Perry, 1994), which were augmented (and in some cases exchanged) with other Kress objects during the following decades. By the end of the 1960s, the remainder of the Kress Collection had been distributed to nearly 100 different museums, universities, and other institutions across the United States, making great European art widely accessible to average Americans.

The database was built primarily upon data gathered from the Kress Foundation and the Gallery Archives by Lauren's predecessor Fulvia Zaninelli, with substantial help from other gallery staff. At the beginning 2012, Lauren participated in an hour long webinar on using Viewshare. After participating in the workshop Lauren decided to experiment and use Viewshare with some of the data from the Kress History and Conservation Database Project to explore the potential uses of the platform. In a matter of hours Lauren had created this interface and visualization of the collection, shown in Image 1 below. (Interact with the functioning view which will open in a separate window). It is important to note that while the database is largely complete, its data is not yet final or comprehensive and should not be cited for scholarly use. We will briefly describe the process Lauren worked through to build the view and then explicate what the resulting view communicates about the collection data.

Exporting, Uploading, Describing and Augmenting Data

Lauren began by exporting data on a subset of database objects, the 887 paintings in the Kress Collection for which purchase price information is known. Once in a spreadsheet, the data could easily be opened, examined, changed, and saved before upload. For example, Lauren collected image URLs for a selected group of paintings from thumbnails on the Kress Foundation website and collection catalogs of Kress institutions, which she added to the spreadsheet before importing the data to Viewshare. For documentation and examples of the data import process you can review the documentation for importing collection data. After uploading collection data, it was possible to quickly describe the data by identifying those fields containing URLs, image URLs, and numerical data. After identifying existing city and state data as locations, Lauren chose to use Viewshare's data augmentation function to derive place names from points of latitude and longitude for each of the museums where a painting is located. Data augmentation is one the built-in features of Viewshare that allows the platform to facilitate the use of heterogeneous metadata and convert that data into standardized formation to enable its use in creating dynamic interfaces. Similar to Viewshare's ability to derive place names into geo-coordinates for map interfaces, it can also derive dates in the ISO 8601 standard format for creating timelines and converts replicated data element metadata fields into a single field array. Once Lauren's dataset had been described and augmented, it was possible to begin building interfaces to her collection.

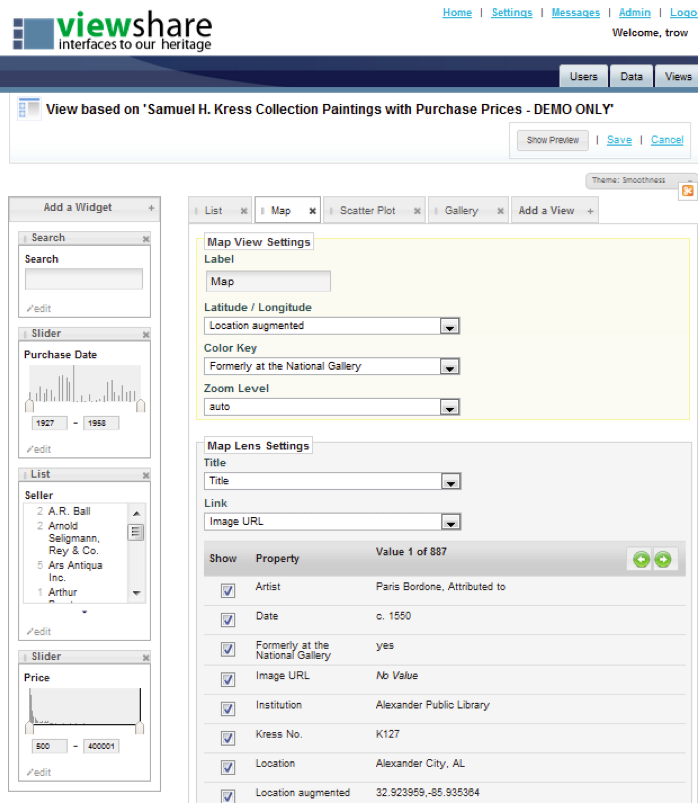

Building the View

If you request a Viewshare account, you can follow these directions to build out your own copy of this interface from the demo Kress collection data set. In Image 2 below you can see a screenshot of the view building workspace, in this case the screen for building a map display. Using simple drag and drop features and basic menus, you add widgets (like a search box, histogram sliders, lists and weighted tag clouds) that will control what is displayed in any of the displays. As you add each individual widget you are presented with the available data fields that can be used with that facet and a preview of what the resulting widget would look like with the given data field. A Viewshare view can be composed of many different displays, located on tabs at the top of the platform window. In the center pane, users can click between the tabs for each of the views and click the "add view" tab to create additional displays (maps, pie charts, scatter plots, lists, and image galleries). Each display can show different metadata elements from the overall dataset. Once you create a new display, you then set what data fields you want to use to power it, for example by selecting which data field has latitude and longitude information in it. You can drag and drop the data fields to reorder them and use the checkboxes to decide which data fields you do and do not want to appear in each display. At any point in the process, users can click the "show preview" button at the top-right of the workspace to see what the final view will look like. This iterative workflow — toggling back and forth between display previews and the display builder — is key to the design process and the act of exploring the relations within collection metadata.

Now that we have explained how one can build this view, we will take some time walking through exactly what this interface communicates and offers. The reader is also advised to open the Kress Collection view in a new tab (using this link) in their browser in order to easily toggle between this article's elucidation of the view's meaning and the fully functioning view itself.

Image 2: Viewshare View Building Workspace (Map Display)

Image 2: Viewshare View Building Workspace (Map Display)

What the Demo Kress Collection View Accomplishes and Communicates

Viewshare's power lies in evidencing collection trends while maintaining item-level accessibility. The Kress database unites information for nearly every collection object to create a resource for object-based study of the complex relationships between Kress, his dealers, the works themselves, the National Gallery, and the other institutions that possess Kress-donated items. Viewshare helps tell the wider story of the collection as a body of objects with a shared history, making otherwise hidden data patterns evident and creating new knowledge through an iterative design and use process. Its data visualizations empower user interpretations, but are built upon the core knowledge of the content stewards who define the dataset and create the tools, and thus the potential and limitations, of the views and facets.

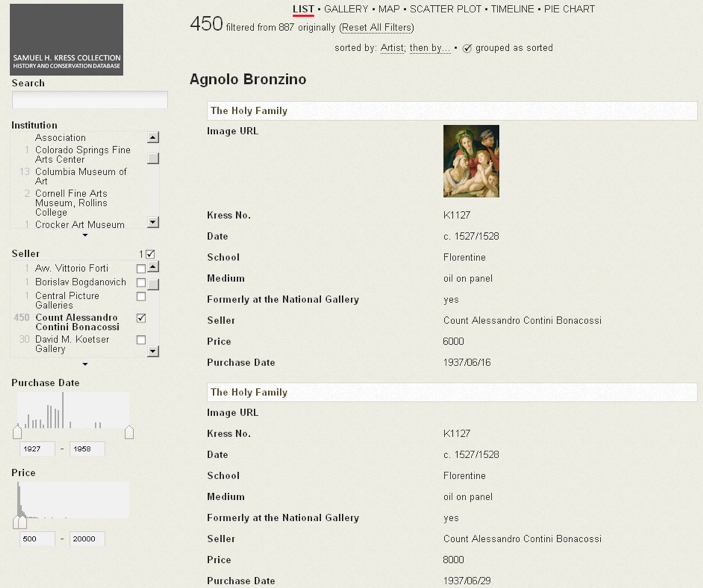

Image 3: The Kress Collection View (List Display)

Image 3: The Kress Collection View (List Display)

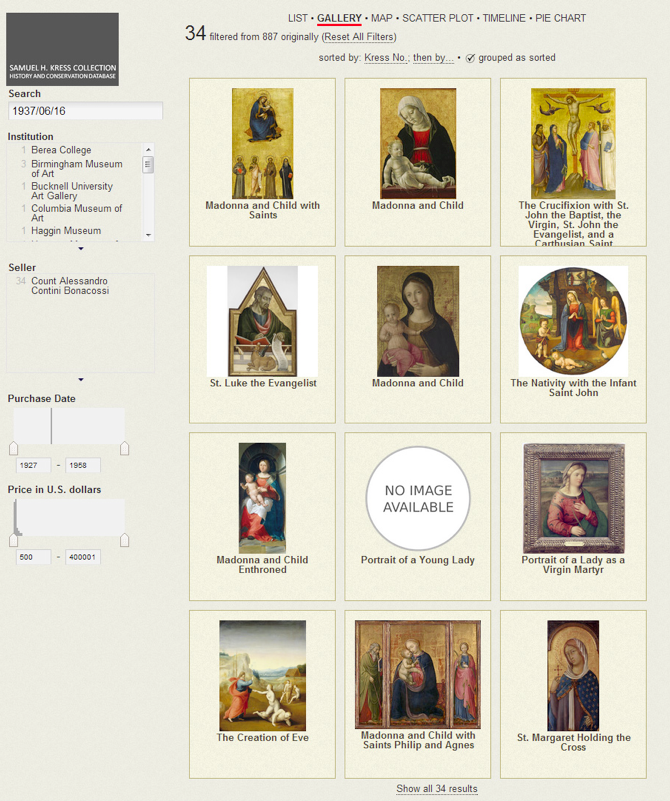

Image 4: The Kress Collection View (Gallery Display)

Image 4: The Kress Collection View (Gallery Display)

On the surface, the list and gallery displays (Image 3 and Image 4) are simple inventories of all the imported records. However, these views expand the existing object-based framework of the data by allowing users to easily create complex queries exposing found sets for immediate analysis. This exploration of the collection occurs through the use of the widgets which allow faceted sorting and other tools. In the Kress Collection displays shown above, users can choose to look only at objects tied to a specific institution or sold by a specific dealer, such as Count Alessandro Contini Bonacossi. At the same time, users can use the histograms and numeric sliders to further define their query by purchase date and purchase price. As an example, a histogram widget of the date span of Contini purchases shows that the Kress purchases from the seller peaked in 1940 and then ceased for nearly a decade, as seen in Image 3 (note the checked box in the Seller facet and the resulting histogram in the Purchase Date widget). This gap in purchases from the Italian dealer can be linked to the impact of World War II on the art market. The found set can also quickly be moved to look only at objects purchased after 1948 so that the specific details of these later purchases can be examined.

Switching over to a gallery display (Image 4), users can see the images of their found set and investigate if a shared purchase history results in common aesthetic attributes or offers novel insights into features of the collection not immediately evident in the metadata or objects themselves. This view shows images of the paintings and allows Lauren to easily link back to the image sources by designating the image title as a hyperlink. The facets and histogram widgets update automatically as the selection of objects is widened or narrowed to show related information including custodial institutions, sellers, purchase dates and a price range for only the current group of paintings. Advanced search and faceted selection will be familiar to many users from other web tools such as traditional online public access catalogs. Viewshare augments these tools by allowing users to see the results of such searching automatically displayed in a variety of visualizations and to toggle between multiple visualizations of the same data set to reveal shared characteristics, leading to a new understanding of the collection objects.

For example, all of the items purchased on a single date can be examined in each display, highlighting shared and/or disparate characteristics among the same group. Image 4 shows a gallery of objects purchased by Kress from Contini on June 16, 1937 (all of which appear on the same bill of sale); in this display one can easily see the visual connections between the works. All but 5 of the 34 paintings are of religious subjects and many feature a gold background. By toggling to pie chart view and looking at the same group of works by media used, one can find that their similar appearances were achieved through similar means — most of them painted using oil or tempera paints, often on wood panel and sometimes with gold leaf applied.

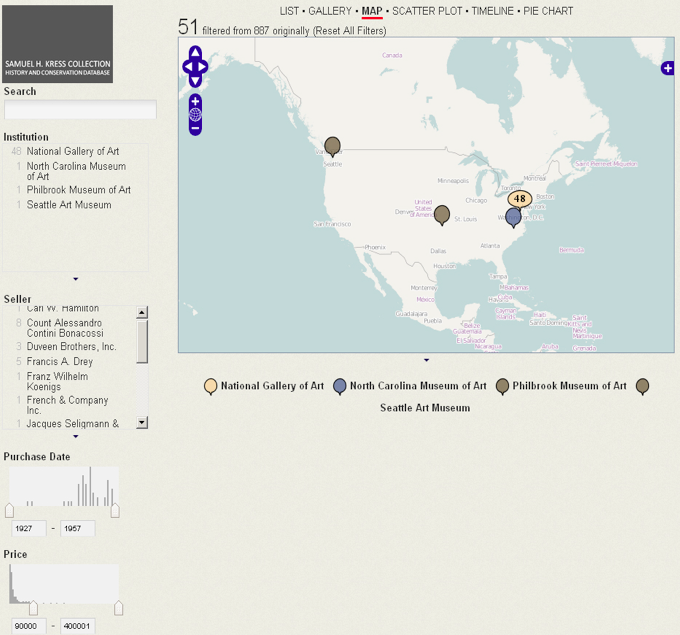

Image 5: The Kress Collection View (Map Display)

Image 5: The Kress Collection View (Map Display)

The map display allows users to observe how Kress objects are geographically dispersed by attribute. Using the numeric slider widget to define a price range of $90,000 and above, as seen in Image 5, one can learn that all but 3 of the 51 most expensive works were given to the National Gallery of Art. Gallery staff, particularly chief curator John Walker, worked closely with the Kress Foundation to evaluate the collection and indicate which works they wished to come to the Gallery (Perry, 1994). Examining the data within the historically close relationship between the Gallery and the Kress Foundation highlights that while widespread, distribution of Kress art was not uniform.

The map display engenders other avenues of exploration since, as in all of the views, when one facet is defined, the information available in the other facets is updated along with the view itself. In the above example (Image 5), one can see within the Purchase Date histogram that most of these expensive works were purchased later in the time span of this collection. The Seller list widget shows the names of the dealers of these 51 works and a quick look at the number of entries by each name shows which seller handled primarily high-priced works. Playing with these widgets in the map view exposes how the collection was dispersed over the time frame in which Kress bought and donated the items in this collection. For distributed collections like the Kress Collection, Viewshare's displays unify the items in a way not feasible in traditional catalogs and offers new methods of analysis and interpretation.

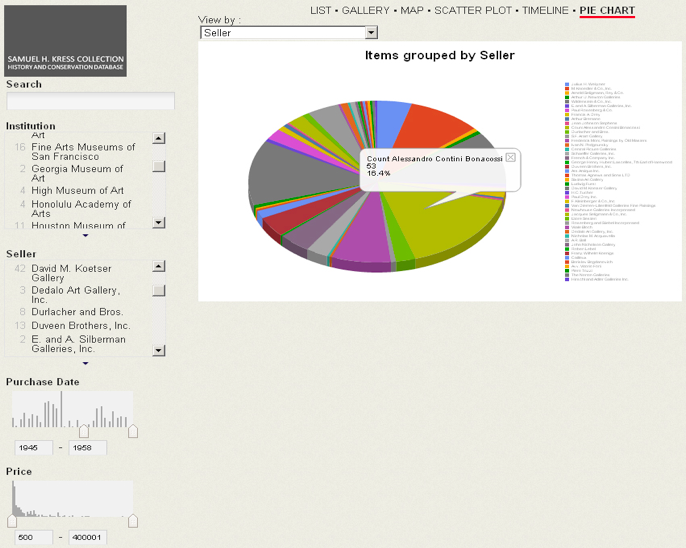

Image 6: Kress Collection View (Pie Chart Display)

Image 6: Kress Collection View (Pie Chart Display)

Pie charts show the distribution of object facets among the data set. For example, in the Kress Collection users can continue to explore the relationship between seller and collector by looking at the percentage of paintings sold by specific art dealers. Overall, Count Contini sold 64.5% of the paintings. By using a date slider widget, we can determine that among paintings purchased by Kress before 1945, Contini was the seller for 92%. Conversely, as seen in Image 6, he sold only 19.6% of the paintings purchased by the Kress Foundation from 1945 to 1955. By placing this data of the context of known Kress history (and keeping in mind the difficulty of buying from the Italian dealer during World War II), the shift aligns closely with Rush Kress taking on leadership of the Foundation from his ailing brother and transforming the collection in terms of quality, focus, and scope (Bowron, 1994).

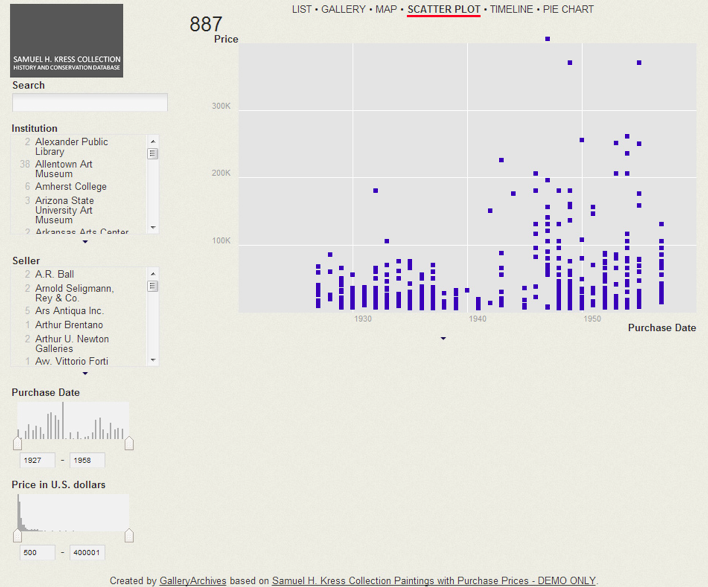

Image 7: Kress Collection View (Scatterplot Display)

Image 7: Kress Collection View (Scatterplot Display)

Another informative Viewshare interface to the collection is the scatterplot view. Scatterplots illustrate the relationship between two quantifiable sets of data. In the case of the Kress Collection, a scatterplot charting paintings' purchase prices in relation to their purchase dates creates a visual representation of Kress collecting habits over time. Looking at the entire data set as shown in the scatterplot in Image 7, it appears that Kress purchased more expensive works later in the formation of the collection, with the upwards distribution of prices beginning in the mid-1940s. One notes that this willingness to pay more for paintings, like the decline in purchases of paintings from Contini, coincides with Rush Kress becoming president of the Kress Foundation.

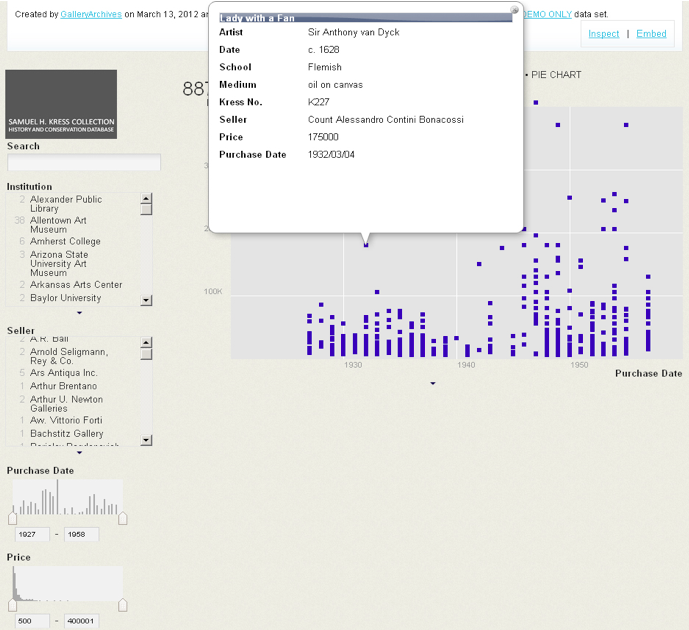

Image 8: Kress Collection View (Scatterplot Display, with outlier information)

Image 8: Kress Collection View (Scatterplot Display, with outlier information)

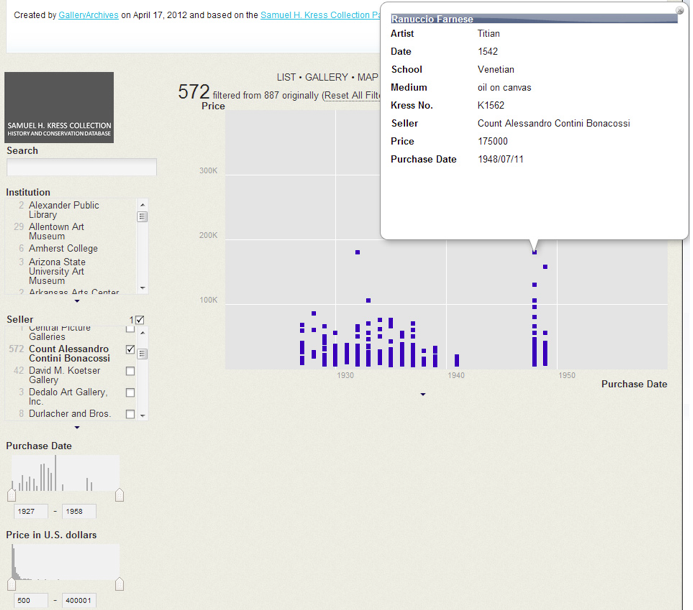

Image 9: Kress Collection View (Scatterplot Display, with seller facet selected and outlier information)

Image 9: Kress Collection View (Scatterplot Display, with seller facet selected and outlier information)

The scatterplot also makes it easy to find and probe outliers, giving users an analytical entry-point organized around knowledge formation, not directed query. As seen in Image 8, by clicking on an outlier early in the Kress Collection formation, a 1932 purchase of a painting for $175,000, the user sees that the work is Lady with a Fan by Sir Anthony van Dyck, sold by Count Contini. Continuing to browse and using the Seller widget to view only purchases from Contini, one can find that this price is matched in the 1948 purchase of Titian's portrait of Ranuccio Farnese (as seen in Image 9). Though this piece is another outlier among Contini sales, the Titian does not stand out as a particularly expensive piece among the higher prices paid by the Kress Foundation to most dealers during the 1940s and 1950s.

Taken together, these tools and display provide a method of interacting with the Kress collection that unearths new and unforeseen contextual detail about the relationships between items, their provenance, and the collection's origins and evolution. Viewshare allowed Lauren to quickly build views which define and combine very granular information — such as items within a specific price, date of purchase, sold by a single seller, and held by a single institution — and then see the results in a variety of interfaces, including charts, image galleries, and catalog records. Lauren's knowledge of the collection was essential to creating the views. Viewshare amplified and refined that knowledge while creating new methods to explore the Kress collection.

What the Implementation of Viewshare Accomplishes and Communicates

The final results, the interface composed of multiple displays, is invaluable in exploring and understanding the Kress Collection. But Viewshare as a tool and a process ended up having additional benefit both for this dataset and for the National Gallery of Art itself. Viewshare can be used for "poking around" in data and uncovering its hidden potential and contexts. Data becomes relational in entirely new ways, both as an iterative process of discovery and as a visualized set of connections and dependencies. Viewshare thus creates a product but also frames a workflow for metadata management. The exploratory process of building views reveals the inconsistencies and limitation within datasets while at the same time showing new ways that it can be used. In addition to creating new access points and perspectives on the data, Viewshare served the Kress Project as a testbed for development of web requirements, as the relational database built by the project is likely destined for public accessibility through a more robust, scalable web portal. Viewshare allowed staff a free and easy way to play with web features and presentation, to reveal new themes and patterns around which descriptive metadata can be improved, and to help imagine how future web display and content management systems would handle existing collection information. Viewshare became a piece of the larger workflow around managing collection data, testing its possible augmentation, management, exhibition, and interactivity.

The Kress collection also demonstrates the collaborative possibilities emphasized in the Viewshare interface. Post-custodial, distributed collections are dependent upon the work and contributions of multiple institutions and not all of them will have a single archivist or collection manager dedicated to sanitizing and administering collection-wide data. In this sense, unifying distributed collections in Viewshare prompts institutions to ensure that collection information is transferable and standardized. Once they started using Viewshare to explore their data, the National Gallery of Art discovered other ideas for potentially linking with distributed collections held partially at the National Gallery and partially at different institutions. Other Viewshare users have similarly explored building views that serve as a collection of collections or a unified point of entry to disparate, but related, groups of materials. In these cases, the implementation of Viewshare has both created a dynamic, interactive way for users to visualize and explore digital collections and also allowed institutions and content managers themselves to discover more about their own institutional workflows and processes. The platform can serve as both a gateway and a testbed, a dynamic interface to a collection and a proof of concept or proving ground for what is possible when exhibiting digital collections. Using Viewshare empowers creators to better understand their collections and to better refine their existing practices around digital collection management, description, and display.

Conclusion

The use case explicated in this article shows both the external and the internal benefits possible through data visualization and procedural testing using Viewshare. The views created in Viewshare give external users an interactive interface that can be employed for generative interpretation and investigation of online digital collections. At the same time it provides the collection managers building those views a free, easy-to-use tool to probe the strengths and limitations of collection metadata. It also aids them in prototyping new workflows for digital collection management, generating new ideas for providing single points of entry to distributed collections, and exploring the possibilities for linking and uniting collections. The affordances of using Viewshare are manifold, helping institutions better serve their users, better understand their collections, and better plan and test new methods of exhibition and access.

References

[1] Bailey, Jefferson and Trevor Owens. "From Records to Data with Viewshare: An Argument. An Interface. A Design." Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. Vol 38, No. 4 (April/May 2012), 41-44 .

[2] Borgman, C.L. (2009) The Digital Future is Now: A Call to Action for the Humanities. Digital Humanities Quarterly.

[3] Bowron, Edgar Peters. "The Kress Brothers and Their 'Bucolic Pictures'" in A Gift to America: masterpieces of European painting from the Samuel H. Kress Collection, Ishikawa, Chiyo, Marilyn Perry, and Edgar Peters Bowron, 41-59. Abrams, New York. 1994.

[4] Drucker, J. Graphesis: Visual Knowledge Production and Representation. Poetess Archive Journal 2, No. 1 (December 10, 2010).

[5] Gibbs, F., Owens, T. Hermeneutics of Data and Historical Writing in Dougherty, J. and Nawrotzki, K. ed. Writing History in the Digital Age, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, forthcoming.

[6] Heer, J., & Shneiderman, B. (2012). Interactive Dynamics for Visual Analysis. Queue, 10(2), 30.

[7] Jessop, M. (2008) Digital Visualization as a Scholarly Activity. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 23, no. 3. 281 -293.

[8] Moretti, F. Graphs, Maps, Trees. Verson, London, 2005.

[9] Perry, Marilyn. "The Kress Collection" in A Gift to America: masterpieces of European painting from the Samuel H. Kress Collection, Ishikawa, Chiyo, Marilyn Perry, and Edgar Peters Bowron, 12-35. Abrams, New York. 1994.

[10] Ramsey, S. (Forthcoming) The Hermeneutics of Screwing Around. in Kee, K. ed. PastPlay: History, Technology and the Return to Playfulness. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver.

[11] Staley, D. Computers, Visualization, and History: How New Technology Will Transform Our Understanding of the Past. M.E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY, 2003.

About the Authors

|

Lauren Algee is the Kress Project Archivist at the National Gallery of Art, Gallery Archives in Washington, DC. In her current position, she manages the Samuel H. Kress Collection History and Conservation Database and is planning the large-scale digitization of documents pertaining to the Kress Collection's acquisition, dispersal, and conservation. A Certified Archivist, she received her Masters of Information Studies and a Certificate of Advanced Study in Preservation Administration from the University of Texas School of Information.

|

|

Jefferson Bailey is Strategic Initiatives Manager at Metropolitan New York Library Council. He previously worked in the Office of Strategic Initiatives at the Library of Congress in the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program (NDIIPP) and Digital Preservation Outreach and Education (DPOE) program. He has managed digital projects at Brooklyn Public Library and the Frick Art Reference Library and has done archival work at NARA and NASA.

|

|

Trevor Owens is a Digital Archivist with the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program (NDIIPP) in the Office of Strategic Initiatives at the Library of Congress. At the Library of Congress, he works on the open source Viewshare cultural heritage collection visualization tool, as a member of the communications team, and as the co-chair for the National Digital Stewardship Alliance's Infrastructure working group. Before joining the Library of Congress he was the community lead for the Zotero project at the Center for History and New Media and before that managed outreach for the Games, Learning, and Society Conference.

|

|