D-Lib Magazine

November/December 2013

Volume 19, Number 11/12

Table of Contents

2012 Census of Open Access Repositories in Germany: Turning Perceived Knowledge Into Sound Understanding

Paul Vierkant

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

paul.vierkant@hu-berlin.de

doi:10.1045/november2013-vierkant

Printer-friendly Version

Abstract

Germany's open access repository landscape is one of the largest in the world. It is shaped by institutional, subject and cross-institutional repositories serving different needs which range, for example, from a mere theses server to a repository integrated into an institutional information infrastructure. To date this landscape has never been fully surveyed. This article presents and interprets the results of a 2012 Census of Open Access Repositories in Germany. This Census covered crucial issues ranging from repository size and software, various value-added services, to general aspects of open access. The key findings of this survey shall help stakeholders in their decision making by identifying trends in the development of open access repositories in Germany.

Introduction

In early 2012 I came across an interesting study that investigated deposit rates in Dutch open access repositories. The so called "Census of Open Access repositories in the Netherlands" covered among other aspects issues such as location and document type of deposit. [1] The data used in this study was collected from NARCIS, the National Academic Research and Collaborations Information System [2], a national information infrastructure which also facilitates easy information gathering, such as this sort of study. This was a perfect example of a study influencing other ideas: it made me wonder about the situation of publication deposits in German open access repositories.

Several extensive studies on institutional repositories have been conducted in North America [3,4]. However, although I have worked as an open access professional and advocate for a number of years, I had never heard of such a comparative study in Germany. This was especially irritating since Germany and its repositories had seemed to be at the forefront of the open access movement for quite sometime. The more I thought about the development of open access repositories in Germany, and my alleged knowledge of it, the more I was convinced that my thoughts did not have any kind of empirical basis. Looking back into the mist of the past it seemed unclear whether it was just a few steps that we progressed, or rather a long and winding road that we had taken.

This uncertainty as to how to evaluate earlier achievements is best described by Ulrich Herb's critical article on how Germany's open access community has become too harmonic lacking friction and self-reflection [5]. In this context, the absence of a study covering Germany's green road — its open access repositories — seems odd given the fact that Germany has a strong open access community. Hence, the present 2012 Census of Open Access Repositories (hereinafter "Census") tries to fill this knowledge gap by assessing different characteristics of open access repositories in Germany. It is fully recognized that other surveys have previously been conducted in Germany. The data collected, however, concentrated on just a small amount of repositories and less issues — too small to draw general conclusions for all of Germany [6], [7]. Having taken a holistic approach from the start, it soon became clear that the Census would need future iterations to improve its structure and broaden its horizon, providing a solid basis for future evaluations of open access repositories in Germany.

The goal of the Census was therefore to analyze as many aspects of an open access repository from different perspectives as possible. It should be noted that this survey is not flawless, but rather a first effort to be improved in future iterations. The results of this effort shall point out best practice examples and help stakeholders to improve open access repositories on different levels in Germany.

Materials and Methods

Realizing the idea of a Census of open access repositories at the Information Management Department at the Berlin School of Library and Information Science was only possible due to the diligent and (voluntarily) effort of Michaela Voigt, Jens Dupski, Sammy David and myself. Designing the Census from scratch, all kinds of questions touching technical, functional as well as structural issues were raised, collected and discussed. We soon discovered that in order to be able to answer all questions raised, we would have to do a survey interviewing repository managers. Due to limited resources however, we opted not to interview repository managers. Instead, we decided to autonomously check the web pages of the open access repositories for issues that could be addressed (semi-) automatically or where citable resources offered reliable data. This approach was certainly a more laborious one, yet by doing so we did not depend on the answers of repository managers, as that would have very likely resulted in a low response rate adversely affecting the data collected.

Even at this stage in the Census we discovered that any future Census should cover the following issues (not exhaustive):

- Is the repository integrated into a CRIS (Current Research Information System) or University bibliography?

- Is the upload form of the repository open to users or is it restricted (e.g. registration, fee, etc.) or even closed (e.g. institutional affiliation)?

- Which persistent identifier system (e.g. DOI, URN, etc.) does the repository support?

- Which licenses (Creative Commons, deposit licenses, etc.) does the repository support?

- Does the repository offer "enhanced publications"?

- Does the repository support versioning of publications?

- Which author identifier system (ORCID, PND, etc.) does the repository support?

- Does the institution responsible for the repository have a corresponding open access policy?

In addition, we discovered the urgent need for an adequate definition of what actually makes up an open access repository. This should differentiate between institutional and subject repositories. Despite extensive research no definition suited the need of our study to classify open access repositories. We therefore developed the following definition:

The Census "[...] definition of Open Access Repository includes repositories that are institutional, cross-institutional or disciplinary providing (in the majority of cases) full-text open access scientific publications together with descriptive metadata through a GUI (with search/browse functionality). The repositories are registered with a functioning and harvestable base URL in at least one of the following registries: ROAR, OpenDOAR, OAI, DINI and BASE." [8]

It is worth noting that we did not take into account digital collections, open access journal (aggregators) or research data repositories, despite the fact that these services are listed in open access repository registries, and despite fitting a broader interpretation of an open access repository. Our decision not to include them was based on the fact that because the structure, scope and content of these services are very different in character, they are difficult to compare.

Altogether, 293 services (including several duplicates) were found in all five registries, out of which the total number of 141 (date of survey: 2012-02-14) offered a functioning and harvestable base URL and at the same time suited our definition of an open access repository (Data was collected from 2012-03-09 until 2012-09-20.) [9].

It is worth returning to the aforementioned questions raised in the design of the Census. The following aspects of an open access repository were addressed in the study:

- size of open access repositories by means of amount of content

- geographical distribution of open access repositories on a national level

- open access repository hosting services

- value-added services

- language support of open access repositories

- open access repository software

- metadata formats

- open access repository registries

- support of the open access movement (e.g. Open Access Fund)

Results and Discussion

Size of Open Access Repositories

To get an overview of how much content German open access repositories really provide, we looked to the most important service provider of open access resources: the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) which supplied us with the number of open access items held in each German open access repository. The repository size of open access repositories not listed in BASE (BASE covered 94%, see also Registries of Open Access Repositories) or with a temporarily unavailable base-URL were manually checked on the websites of the respective repository the very same day (date of survey 2012-09-14).

We preferred using the term "item" in contrast to "document" or "publication" due to several reasons. First of all, despite the focus on publications there might be all kinds of data formats (e.g. audiovisual and PowerPoint files) in a repository. Secondly and even more important a harvesting service cannot verify whether a metadata entry has a full text or not. BASE states that "[a]bout 70-80% of the indexed documents in BASE are open access, the rest are mere metadata entries without full text or can only be accessed, if you are authorized for accessing this particular data source." [10]

Due to the enormous difference in size between the smallest and the largest repository and to keep up comparability we categorized them into three size ranges each covering a similar number of open access repositories (see Table 1).

Table 1: Size ranges of open access repositories in Germany

| Size ranges of open access items |

Total number of open access repositories (%) |

| 1 — 1,000 (small) |

57 (41%) |

| 1,001 — 5,000 (medium) |

47 (33%) |

| 5,001 — 50,000 (large) |

37 (26%) |

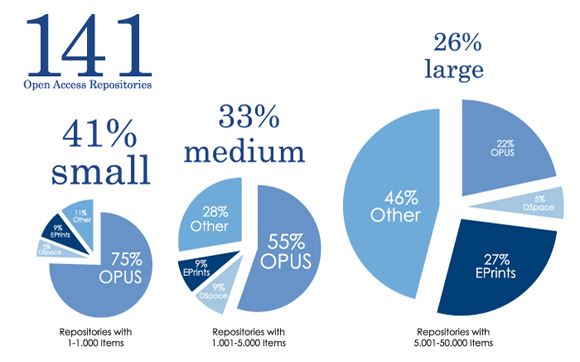

Repositories containing 1-1,000 open access items make up the biggest share (41%) of all 141 German open access repositories. This might result from limited (financial) resources to promote the local service but also the fact that the institutions running these repositories are indeed small. To identify the reasons for this correlation, a future Census will have to classify the repositories according to their function (see the Materials and Methods section above). Such a future Census could categorize a responsible institution according to its type [11]. Knowing the type of higher education institution or research institution (both hereinafter: "institution") could tell us which institutions actually run a repository.

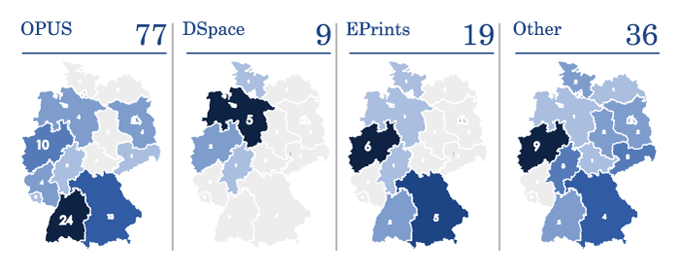

Figure 1: Size ranges of and software used for open access repositories in Germany.

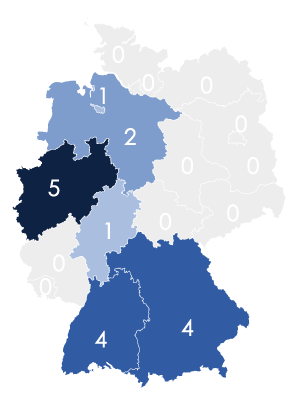

Taking all 141 open access repositories in Germany into account, the total number of items is 704,121, resulting in an average size of 4,994 items. Most of Germany's open access repositories can be found in the most heavily populated Länder North Rhine-Westphalia (27), Baden-Württemberg (28) and Bavaria (22). A possible correlation between the number of institutions in a Land and the number of repositories per Land will again be assessed in a future Census.

Among the top five of the largest open access repositories there are four subject based repositories (see Table 2). This result supports the hypothesis that researchers — due to higher visibility in their community — are more willing to deposit their works in subject based repositories than in the repository of their home institution. However, a closer look at the big players reveals that the large number of working papers, conference proceedings, etc., seems to inflate the size of subject based repositories. This is probably due to the publishing behaviour of the researchers in the respective fields such as economic science (EconStor).

Table 2: Top 5 largest open access repositories in Germany

| Repository |

Number of Items |

| 1. elib Publikationen des DLR |

46,136 |

| 2. EconStor |

45,268 |

| 3. German Medical Science |

41,753 |

| 4. PUB - Universität Bielefeld |

32,695 |

| 5. ePIC — AWI |

29,480 |

Hosting of Open Access Repositories

An interesting aspect of hosting open access repositories is how many, and what kind of, institutions are clients of hosting services. To find out how many open access repositories are hosted, the websites of hosting services in Germany were used as a reference (date of survey 2012-04-24) [12-15].

The main findings were that about one third of Germany's open access repositories are hosted — this reflects the key role hosting services play. Of these 53 repositories nearly all installations (51) are running the German repository software OPUS. This result confirms the impression that Germany is an "OPUS country". Especially the southern Länder geographically reflect the history of the OPUS software which originated from a research project (see the Software section below). Moreover, looking at the size of hosted repositories it becomes clear that about 60% of the small repositories are hosted, whereas only a minor part of the larger repositories use this service (see Table 3).

Table 3: Share of hosted open access repositories in Germany

| Size ranges of open access items |

Total number of

open access repositories |

Total number of hosted

open access repositories (%) |

| 1 — 1,000 (small) |

57 |

34 (60%) |

| 1,001 — 5,000 (medium) |

47 |

14 (30%) |

| 5,001 — 50,000 (large) |

37 |

5 (14%) |

Language Support

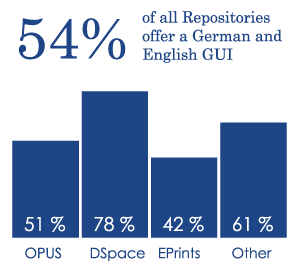

Since open access knows no borders, and since most German institutions claim to be international, we studied how many open access repositories offer a German and English GUI. One in two of all open access repositories offer a bilingual user interface (76 of 141 repositories, representing 54%, see Figure 2 above). The bigger a repository the more likely it supports both languages. Main factors might be that smaller institutions do not have an international scope or do not have the resources to maintain all provided information (policies, FAQ, deposit license, etc.) in English. Furthermore, it is questionable that users searching for publications use an open access repository as a primary search entry and therefore an English GUI would not justify the effort needed.

Figure 2: Repositories running the respective software offering a German and English GUI.

Nonetheless, to improve the repository service for non-German researchers at their institution who deposit their publications in the repository, it is recommended that repositories and hosting services should make some effort to internationalize their services.

Value-added Services

Most value-added services that have been around for years are not common in several German open access repositories. The present census covers basic services of an open access repository within the following parameters:

- Bibliographic export (at least one format, e.g. RIS) is available on item or collection level.

- Usage statistics (e.g. downloads, views) are available for unregistered users on item level.

- Checksums (e.g. MD5, SHA1) of full-text publications are available on item level.

- A functioning RSS feed is available on the home or browsing page.

- Social bookmarking (at least one service, e.g. delicious) is available on item level.

- Social networking (at least one service, e.g. Facebook, Twitter or AddThis) is available on item level.

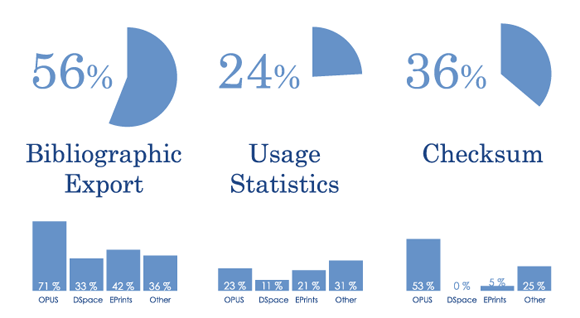

Bibliographic Export

Bibliographic export is supported by only 56% of all open access repositories offering standard formats like RIS or BibTeX (meaning that at least one format, e.g. RIS is available on item or collection level). It is noteworthy that OPUS is by far the best repository software to choose when looking for bibliographic export (71% of all OPUS repositories, see Figure 3). This result is confirmed by the rather astonishing discovery that the smaller a repository, the more likely it supports bibliographic export. Giving back the metadata to the researchers that often painstakingly produced them, makes bibliographic export the most important value-added service of an open access repository. Repository operators should therefore consider offering bibliographic export, especially for researchers that use reference management systems.

Figure 3: Value-added services supported by open access repositories and repository software.

Usage Statistics

Interest in alternative metrics to measure the impact and importance of scientific works is growing. It thus seems rather odd to find that only one quarter of all open access repositories in Germany offer usage statistics, such as the number of downloads or views available for unregistered users on item level (see Figure 3). The following is less surprising, though: the bigger a repository, the more likely it is to offer usage statistics. This may be due to the fact that larger institutions try to find new ways to measure and quantify the success of their publication output. This kind of institutional evaluation is also asked for by funding organizations. The small number of repositories offering public usage statistics for its users clearly shows the need for projects such as Open Access Statistics that try to promote internationally comparable usage statistics in Germany [16].

Besides bibliographic export, providing usage statistics is another crucial value-added service that researchers can directly benefit from. In times of "publish or perish" such metrics are more than just numbers. They can influence hiring and promotion of researchers or funding of research projects. Moreover, such statistics could provide new arguments for the potential impact of open access publications that once had the status of being closed access.

Checksums

The provision of checksums to detect integrity and authenticity is offered by repositories (a somewhat technical service, focusing on long term archiving aspects). Availability of checksums (e.g. MD5, SHA1) of full-text publications on item level is supported by 36% of open access repositories in Germany. One in two OPUS installations offers checksums; making the German repository software the leading product in this category [17]. This finding is supported by the surprising correlation that the bigger a repository, the less likely it is to publicly provide a checksum. Larger institutions seem to question the spirit and purpose of checksums as a basic tool for researchers when they decide not to publicly offer this information although their software supports it. Repository operators should internally track the integrity and authenticity of their stored documents, however from a researchers point of view the relevance of checksums seems questionable.

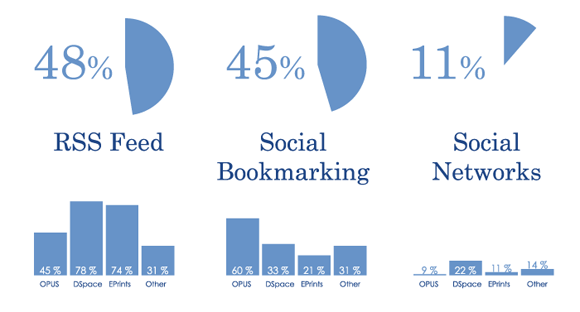

Figure 4: Value-added services supported by open access repositories and repository software.

RSS Feed

If a website offers an RSS feed it provides a common service to regularly supply users with information. Almost half of all German open access repositories support this tool for researchers to monitor repository content on the home or browsing page (see Figure 4). When it comes to RSS feeds, size doesn't matter: Small, medium and large repositories are equally likely to offer this basic service. Since the usual usage of an RSS feed is subject oriented the need for such a service depends on the kind of repository. It is unlikely that researchers subscribe to an RSS feed from their institutional repository which already covers publications from all academic fields present at the institution. However, an RSS feed of a subject repository is certainly a realistic use case that the repository operators should consider.

Social Bookmarking

Social bookmarking is an informational tool of the Web 2.0 era. As with RSS feeds, about one in two German open access repositories support social bookmarking, meaning that at least one service, e.g. delicious, is available on item level (see Figure 4). Most repositories running OPUS provide social bookmarking for their users, since older versions of the software offer this service out of the box. Strangely enough, the bigger a repository the less likely it is to support social bookmarking. One reason why the majority of institutions running an open access repository do not support such a tool of information supply and sharing might be that users prefer social bookmarking plugins in their browsers to social bookmarking buttons on websites.

Social Networks

What is true for social bookmarking is even truer for social networks: a mere 11% of all open access repositories in Germany offer at least one service, e.g. Facebook, Twitter or AddThis button on item level (see Figure 4). However, larger institutions use the social web in the academic sphere to enhance the visibility of the publications in their repository. A conclusion one could draw from the correlation is — the bigger a repository, the more likely it has integrated social network functions.

Overall, the Census reveals that the above examined tools are to a large extent not supported as value-added services in German open access repositories. A lack of resources might be one of the main causes for small repositories. Large repositories might be reluctant to offer these services because they might fear the possible efforts needed to set up and maintain them every time there is a software update. Another reason might be that institutions running an open access repository (rightly) question the utility of the examined value-added services.

Open access repositories should aim to be an integrated part of the research and publishing process by offering basic services such as bibliographic export or usage statistics. Services such as social bookmarking and social networks integration could be easily provided by adding an html snippet to the repository web pages. There is still room for improvement in the realm of value-added services in most open access repositories in Germany. Whether this improvement is sought after depends not so much on the resources available, but rather on the self-acceptance by the institutions that they run a repository primarily as a service to their researchers.

Software

Repository software is an issue that touches almost all aspects of the Census: a repository can only be as good as its software. Looking at the different software solutions in Germany, three major players — OPUS, DSpace and EPrints — can be identified apart from several smaller proprietary developments.

With 77 out of 141 repositories using OPUS, a software developed via a joint project of several German Universities funded by the German Research Foundation DFG, Germany can truly be called an "OPUS-country". As mentioned before, due to hosting services, OPUS installations are spread over Germany, though with a strong focus on Southern Germany. Despite difficulties in the development of the latest version, OPUS remains the preferred software mainly because it already is compliant with German specific requirements such as the obligatory deposit of theses to the German National Library (DNB). Additionally, OPUS is used by 75% of all small and 55% of all medium open access repositories (see Figure 1). This could either indicate that OPUS seems to fit the need of smaller institutions or just represent the aforementioned number of OPUS hosted repositories.

DSpace repositories can only be found in the Northwest of Germany (see Figure 5). Only 9 out of 141 are running DSpace — the most widely used repository software in the world. This seems like a rather contradictory situation: Whereas Germany is one of the top three countries regarding the total number of repositories [18], the internationally leading software DSpace (40.6%) is comparatively underrepresented (4.6%). This might stem from the dominance of OPUS.

EPrints is used by 19 institutions primarily from the western and southern parts of Germany (see Figure 5). EPrints was developed in Southampton, UK and seems to be an adequate solution for larger repositories (see Figure 1): five repositories in the top ten of the largest open access repositories in Germany are running the software.

In Germany one in four institutions uses a repository software other than OPUS, DSpace or EPrints to run their open access repository. There are repositories all over Germany running with proprietary developments or less well-known repository software. This is also true for most large repositories with 46% of them running "other" software.

Figure 5: National distribution of repository software in Germany.

[These maps were created using "Locator map Berlin in Germany.svg" by NordNordWest, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC-BY-SA-3.0-DE.]

The 2012 repository landscape of Germany can be characterized by "the national software" OPUS and minor proprietary regional or local developments such as MyCoRe [19]. Furthermore, the software maps also indicate a regional concentration of DSpace and EPrints installations which might stem from possible networking of institutions in the respective Länder.

The development of new features and sustainability are fundamental issues in the choice for a repository software, not least because funding and resources for open access repositories are notoriously low, as a small survey during a DINI repository management workshop in 2012 in Göttingen, Germany, confirmed [20]. This situation will eventually bring German repository operators to choose software that is in use internationally. First steps towards this goal can be seen in:

- the networking of DSpace and EPrints repositories using national mailing lists and workshops to spread their software to build a community that would make new developments of features more feasible;

- the fact that from early 2012 on the Library Service Centre Baden-Wuerttemberg (BSZ), one of the three major hosting services in Germany, offers a DSpace hosting service [21].

With future needs, such as implementing semantic web standards or the integration of repositories into Current Research Information Systems (CRIS), this concentration and evolution of repository software will continue in Germany and beyond.

Metadata Formats

From a librarian's perspective, even more important than size, value-added services and software of an open access repository, are the supported metadata formats. Studying the offered metadata formats gives a bigger picture of which metadata standards are de facto or just theoretical. Prerequisite was that repositories offer their metadata formats via OAI-PMH. The listed metadata formats ("?verb=ListMetadataFormats") were validated. Only de facto functioning metadata formats were taken into account (Period of survey: 2012-06/07).

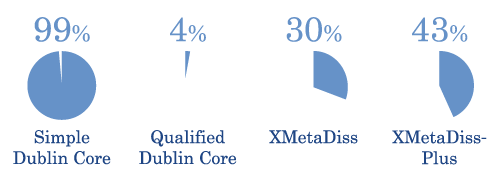

Figure 6: Metadata formats supported by German open access repositories.

Simple Dublin Core is supported by 99% (see Figure 6) of all German open access repositories, which makes it the only de facto metadata standard. Two reasons for the widespread dissemination of Simple DC might be its simplicity and the fact that is has been around many years (dating back to 1998) [22]. Its simplicity is also a reason for the development of more complex metadata formats in the past. However, with a dissemination of merely 4%, Qualified Dublin Core does not seem to have found its way into Germany's open access repositories. Although compatible with Dublin Core, XMetaDiss is supported by less than one third of all German open access repositories (see Figure 6). XMetaDiss is a German metadata format that was introduced in the late 1990's as a national standard for the submission of doctoral dissertations to the German National Library [23]. Its successor XMetaDissPlus did not become a national standard either (43% support XMetaDissPlus, see Figure 6). These figures suggest that either open access repositories use other methods to submit their thesis metadata to the national library or that these repositories do not contain theses and thus do not need this metadata format.

Figure 7: Linked open data supported by German open access repositories.

When it comes to linked data, German open access repositories tend to support semantic web standards such as the Resource Description Framework, RDF [24] (7%) or Open Archives Initiative Object Reuse and Exchange, ORE [25] (2%, see Figure 7). This suggests that there is still a long journey ahead to reach the realm of the semantic web. In sum, the dissemination of metadata standards in German open access repositories is less a result of the number of years of existence than its supposed complexity. Hence, Dublin Core Simple via OAI-PMH is the general rule today, and linked data the exception.

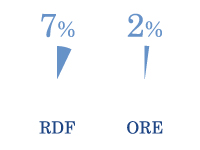

Registries of Open Access Repositories

When it comes to visibility of open access repositories, registries play an essential role. However, the coverage ranges from 56% in the OAI Data Provider List to 94% in BASE (see Figure 8, date of survey: 2012-04-04). In addition to the small number of registered open access repositories, the number of duplicates and outdated base URLs confirm the impression that some of these registries are obsolete. For example, the following repositories have duplicates in ROAR: "Hochschulschriftenserver der Katholischen Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt" is indexed three times (ID: 958, 2391, 3126), the "GKSS Publication Database for Open Access Full Text Documents" twice (ID: 3406, 579), and "Goescholar" twice (ID: 3904, 590). The base URL of the "Volltextserver der Fachhochschule Würzburg-Schweinfurt" is outdated in ROAR (ID 974) and in the OAI Data Provider List (Last checked on 2013-03-14).

Figure 8: Coverage of all 141 German repositories in repository registries.

As a "living" registry depending heavily on the reliability of its sources, the meta search engine BASE is the only registry covering almost all German open access repositories. In order to be listed in the Census, a repository would have to be registered in at least one of the four registries. Bearing that in mind it is surprising that only 40% of Germany's open access repositories were registered in all five registries.

Open Access

The final section of the Census deals with selected issues of the open access movement in Germany. Not the repositories as such but the institutions running an open access repository were examined according to the following measures:

- Signing the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities. (If an umbrella organization, e.g. Helmholtz Association of National Research Centers signed the Berlin Declaration, all subsidiary institutions running an open access repository were counted (date of survey: 2012-04-27) [26].

- Offering an open access publication fund supported by the German Research Foundation DFG, a special fund for articles in fully gold open access journals. (Institutions taking part in the funding program "Open Access Publizieren" date of survey: 2012-04-26) [27].

- Being a member of the Confederation of Open Access Repositories (COAR). (If an umbrella organization, e.g. Helmholtz Association of National Research Centers is a member of COAR, all subsidiary institutions running an open access repository were counted (date of survey: 2012-04-26) [28].

Constituting a reasonable share, more than one quarter of all institutions running open access repositories took at least one of the three measures. Institutions running large repositories are in the majority among those in all three categories. This might be due to the fact larger institutions have either enough staff or resources to support open access at their institution in different ways (e.g. with an open access publication fund) or the administration of these institutions regards open access to be important enough to support it ideologically (e.g. by signing the Berlin Declaration).

Figure 9: Dissemination of DFG supported open access publication funds in Germany.

[This map was created using "Locator map Berlin in Germany.svg" by NordNordWest, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC-BY-SA-3.0-DE]

Looking at the geographical distribution of open access publication funds supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation, DFG) one might think that the German border still existed (see Figure 9). It is surprising that by Spring 2012 not one institution running an open access repository came from the new Länder, i.e., the former East. However, since spring 2012 TU Dresden, TU Chemnitz and FU Berlin offer a DFG-supported open access publication fund. One reason might be that open access plays a minor part and stakeholders in institutions of the German East thus set other priorities than applying for DFG funding. However, it is more likely that most institutions from this region have difficulty meeting the application requirements for DFG funding (e.g. a University bibliography documenting the institutional publication output). These requirements particularly exclude smaller institutions with limited resources from DFG funding. This funding strategy leaves researchers at smaller institutions behind, and benefits researchers working at institutions tha are probably already "open access players." Remedy could be found if the DFG provided open access funds on Länder or even national level so that all researchers in Germany have equal chances to receive funding for their open access publications.

Yet the strength of Germany's open access movement cannot be measured using the present criteria. There is massive support for open access at many German institutions that goes beyond simply being signatories of the Berlin declaration and providing open access funds. With networks such as the Deutsche Initiative für Netzwerkinformation e.V. (German Initiative for Network Information, DINI) [29], Schwerpunktinitiative "Digitale Information" der Allianz der Wissenschaftsorganisationen (Priority Initiative Digital Information) [30], Aktionsbündnis Urheberrecht für Bildung und Wissenschaft (Coalition for Action "Copyright for Education and Research") [31] the German community is at the global forefront of open access. Funding organizations such as the DFG promote open access by funding projects that support the setup of repositories and other services. Open access repositories are a vibrant part of this movement with ever changing roles, ranging from being solely a thesis server to being an integrated part of library retrieval or research information systems.

Conclusions

Touching several essential aspects of an open access repository the 2012 Census of Open Access Repositories in Germany leaves us with the following seven key findings:

- OPUS is the most used repository software in Germany, however a trend towards globally used software such as DSpace and EPrints is visible.

- Simple Dublin Core is by far the only metadata format supported by German open access repositories that deserves to be called a standard.

- In comparison to all other repository registries the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) has the best coverage of German open access repositories.

- More than one quarter of institutions running a repository support open access, in a variety of ways.

- Most small open access repositories in Germany are hosted.

- One in two of all open access repositories in Germany have a bilingual GUI supporting German and English.

- There is a need for more basic value-added services in Germany's open access repositories.

To sum up, the 2012 Census of Open Access Repositories in Germany represents an unprecedented snapshot of Germany's repository landscape providing the community with substantial information about crucial issues of repository management. The Census revealed shortcomings and strengths of repository software supporting institutions with future decisions concerning the development of their repository. Furthermore, the Census indicated the strong and growing open access movement in Germany. Ultimately, the Census points out that most open access repositories in Germany lack basic functions such as bibliographic export, usage statistics, social media or multilingual support today.

The present study provided us with unprecedented findings but left many questions unanswered. The Information Management Department at the Berlin School of Library and Information Science will conduct a future Census of Open Access Repositories in Germany in the course of a seminar that will attempt to address unresolved issues and critically assess its structure and scope [32].

The ascent of the green road to open access heavily depends on visibility, features, and functionalities leading to the acceptance of open access repositories. If uploading, searching and exporting of references is integrated into the everyday life of a researcher, the promotion and uptake of open access will be facilitated. However, the advent of open access in research does not only depend on the repository itself but also on the enduring will of repository managers, funders and other stakeholders to tackle the issues presented in this article.

Acknowledgements

Michaela Voigt, Jens Dupski and Sammy David, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, conceived and performed the study. Credit also goes to Mathias Lösch, University Library Bielefeld, Germany providing essential data from the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) and Maxi Kindling, Prof. Dr. Peter Schirmbacher and Najla Rettberg for their extensive feedback.

References

[1] Gerritsma W (2012) A census of Open Access repositories in the Netherlands. WoW! Wouter on the Web: Comments on the library and information science world.

[2] NARCIS: The gateway to scholarly information in the Netherlands (2013). NARCIS - National Academic Research and Collaborations Information System.

[3] Rieh SY, Markey K, St Jean B, Yakel E, Kim J (2007) Census of institutional repositories in the US: A comparison across institutions at different stages of IR development. D-Lib Magazine 13: 4. http://doi.org/10.1045/november2007-rieh

[4] Markey K, Rieh SY, St. Jean B, Kim J, Yakel E (2007) Census of Institutional Repositories in the United States: MIRACLE Project Research Findings. CLIR Publication No. 140. Council on Library and Information Resources.

[5] Herb U (2012) Die Open-Access-Community: Harmonie, fehlende Reibung und die Vorstellung des goldenen Open Access. Telepolis - Science News.

[6] Windisch N (2009) Repositorien an wissenschaftlichen Einrichtungen: Bestandsaufnahme und Ausblick Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

[7] Offhaus N (2012) Institutionelle Repositorien und Universitätsbibliotheken — Entwicklungsstand und Perspektiven.Köln: Fachhochschule, Institut füür Informationswissenschaft.

[8] Vierkant P, Voigt M, Dupski J, David S, Lösch M (2012) 2012 Census of Open Access Repositories

[9] Vierkant P, Voigt M, David S, Lösch M, Dupski J (2013) 2012 Census of Open Access Repositories in Germany. figshare. http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.677099.

[10] Bielefeld University Library (2013) FAQ — Bielefeld Academic Search Engine. BASE.

[11] German Rectors' Conference (2013) Higher Education Institution. Hochschulkompass.

[12] BSZ (2013) OPUS im Bibliotheksservice-Zentrum Baden-Württemberg.

[13] KOBV (2013) Opus & Archivierung — Referenzen/Teilnehmer.

[14] HBZ (2011) hbz — OPUS.

[15] Open Repository (2013) Customers | Open Repository - Registered DSpace Provider.

[16] DINI e.V. (2013) Why OA-Statistics?.

[17] KOBV (2013) OPUS 4: Überblick.

[18] OpenDOAR (2013) Proportion of Repositories by Country - Worldwide.

[19] MyCoRe (2013) MyCoRe.

[20] DINI e.V. (2012) DINI-Workshop: Repositorymanagement 2012.

[21] BSZ (2013) DSpace.

[22] Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (1998) Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, Version 1.0: Reference Description.

[23] Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (2005) XMetaDiss - eine xml-basierte Struktur für das Metadatenformat MetaDiss.

[24] W3C — RDF Working Group (2004) Resource Description Framework (RDF).

[25] Open Archives Initiative (2013) Object Reuse and Exchange.

[26] Max Planck Society (2013) OA MPG Signatories.

[27] DFG (2013) GEPRIS - Geförderte Projekte Informationssystem.

[28] COAR (2012) Members and Partners by Country.

[29] Deutsche Initiative für Netzwerkinformation e. V. (2013) About DINI.

[30] Allianz der deutschen Wissenschaftsorganisationen (2013) Schwerpunktinitiative "Digitale Information".

[31] Aktionsbündnis "Urheberrecht für Bildung und Wissenschaft" (2013) Coalition for Action "Copyright for Education and Research".

[32] Schirmbacher P, Kindling M (2013) "Die digitale Forschungswelt" als Gegenstand der Forschung. Lehrstuhl Informationsmanagement. Information — Wissenschaft & Praxis 64: 127—136.

About the Author

|

Paul Vierkant is working at the Berlin School of Library and Information Science of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany in the re3data.org project creating a global registry of research data repositories. Prior to his current position he was project manager at the University of Konstanz building a research data repository and institutional repository.

|

|