From her own lifetime onwards, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, has been one of the most controversial historical figures. The gamut of responses to her ranges from admiration for a martyr of the Catholic faith to disgust with the wickedness of an irresistible femme fatale or pity for the defenceless victim of vile machinations on the part of the Scottish and English nobles and/or the Queen of England. The polarisation of opinions about her was particularly prominent in nineteenth-century Britain where she became the subject of historical accounts as far apart as James Anthony Froude's vitriolic History of England (1893, vols. vi-xii), which does not stop short of personal insults, and John Hosack's enthusiastic vindication in Mary Queen of Scots and her Accusers (1870-74). This confrontation is anything but surprising for this period as the Mary Stuart can be understood to embody a cluster of its key anxieties, namely the question of the appropriate feminine role and the character traits with which 'woman' could be taken to be automatically endowed. In official gender concepts like Coventry Patmore's "angel in the house" and John Ruskin's model of "separate spheres", these issues were addressed by proclaiming the inherent and unqualified moral goodness and sexual purity of 'woman', whose activities were naturally grounded in the domestic realm. Recent feminist criticism, however, refuses to take these answers at face value and considers their absoluteness and polished smugness an indication that the real situation was far less comfortable. The dominant image is then given a prescriptive force meant to curb actual or anticipated feminine transgressions and the threat they implied for the social order (e.g. Vickery 1993: 6; Hartnell 1996: 466-473). Quite apart from such a reading against the grain, official conduct books and advice manuals themselves made it clear that a single deviation from the norm would lead to an irrevocable exclusion from the status of 'woman'. They thus implicitly created a second category with darker images of female human beings, which could only gradually be referred to explicitly in humanitarian and sociological treatments of criminal and "fallen" members of the sex.

A brief overview of the most contentious points in the life of Mary Stuart reveals a close relationship between her story and nineteenth-century British gender ideology: It has often been alleged that she had passionate affairs with some of her courtiers during her betrothal and marriage to Lord Darnley. The most notable lovers are said to have been the French poet Chastelard, who followed Mary Stuart to Scotland, her Catholic Italian secretary David Rizzio and the Earl of Bothwell, who then became her third husband. These images violate the ideological requirement of sexual purity not only by the transgressive act of adultery but also - still more subversively - by suggesting the possibility of active sexual desire in a female human being. In addition, the Queen's association with Bothwell led to her implication in the murder of her second husband Darnley at Kirk o'Field in February 1567, even though indisputable evidence was neither found at the time nor when English lawyers tried to procure it towards the end of her life. A similar web of potential forgery and fabrication surrounds Mary's involvement in the failed conspiracy of 1586 by which Anthony Babington wanted to do away with Elizabeth, make the Queen of Scots the new ruler and re-establish Catholicism in England. From a nineteenth-century point of view, it is thus possible to see Mary Stuart as personifying all the characteristics that disqualified a female human being from the title of 'woman'. At the same time, it is equally obvious at which points this image can be inverted to result in a model 'woman' whose inability to penetrate into the power games played by the (obviously existent) different factions of her court only underlined her perfect domesticity. She might also be considered an equally exemplary woman who - along Ruskin's lines - tried to carry the values of home including her deep religious convictions into the public sphere but failed because she was surrounded by enemies. All of the transgressions imputed to the Queen of Scots then turn into slander carefully arranged to be as damaging as possible. Just as the dominant concept of 'woman' in nineteenth-century Britain was constituted by projecting all possible negative traits on to the anti-image, these two contrary characterisations are drawn up one against the other. Factually, they are thus very close and even interdependent, but at the same time there was an acute need in the nineteenth century to stress their utter incompatibility, because otherwise one of the most basic oppositions in social mythology would have collapse - hence the vehemence of the debate about Mary Stuart.

Apart from historical works, the dispute also manifested itself in the drama of the period. As well as lending herself well to the creation of a colourful protagonist, the Queen of Scots after all offered dramatists the advantage of treating a historical subject with a well-established plot outline and the potential for spectacle and lavish period costume without losing topical relevance. Against the background of the polarised debate about Mary Stuart the intertextual context always loomed large, and a play about her could hardly escape being interpreted as a statement in favour of one or the other side. Indeed, when dramatic works are written for performance, they have a particular bearing on an ongoing dispute as they constitute public contributions in the effective form of visual images. This power of the stage has pervasively been acknowledged by state officials through theatrical censorship, which was often - and also in Victorian Britain - still in operation after the control over printed works had been relinquished.

The present analysis will focus on key images of Mary Stuart created in nineteenth-century British plays with regard to her three (possible) love affairs and the murder plot against Darnley. Her potential involvement in Anthony Babington's conspiracy is marginalised in the drama of this period and will therefore be omitted here in favour of the different ways in which the plays end their representation of her life. Whereas endings are of great importance in fictional plots, their centrality in this historical case with a certain and definite final event may not be immediately obvious. However, already a cursory glance at important dramatic works about the Queen of Scots reveals how considerably their last scenes vary, so that one is tempted to assume a relationship between the overall image of Mary Stuart presented in a play and the ending chosen for it.

1. Mary Stuart and Chastelard

This relationship is treated in three very different nineteenth-century works: Francis A.H. Terrell's David Rizzio, Algernon Charles Swinburne's Chastelard (the first part of his Mary Stuart trilogy) and the anonymous Marie Stuart in the Lord Chamberlain's Collection of Plays which was written by William Gorman Wills. Even though Terrell's tragedy of 1882 deals with the period in question, Mary Stuart's possible affair with the Frenchman (here called Chatelar) is not the focus of the drama. Indeed, the Queen herself only appears in Act I, Scene 3, and far more space is given to the disputes among the nobles of her court. The Earl of Morton is particularly prominent, and as the play unfolds, one gradually realises that he is the driving force behind the plot and uses the other characters as ciphers in his power games. This also holds true for the love affair: As Chatelar tells David Rizzio, Morton had him believe that he had found the Queen's favour, which made him go to her and led to his arrest by Rizzio's men. The exact nature of Chatelar's feelings for Mary is not at issue here, and her response does not play a role at all. Although she can thus be pronounced innocent of transgressive passion, the Queen of this tragedy feels guilty that her beauty has brought about the incident, which, however, does not prevent her from giving in to Morton when he urges her to sign Chatelar's death warrant as the only means of vindicating her honour. Without her knowledge, Morton then has the prisoner executed, so that the Queen can no longer change her mind: "I would not trust your honour in the care / Of your compassion" (49). Mary Stuart thus emerges as a puppet queen in this representation who is ruled by Morton and provides ample evidence for woman's general unfitness for the public realm.

Swinburne's poetic tragedy of 1865 gives her much greater scope for independent action and has her reign without an overriding character in the background. She even repeatedly claims she would have preferred to be a man, but it is quite characteristic that she turns out to be unable to wear Chastelard's sword, which she wants to try on (51): Confronted with important decisions, especially with regard to Chastelard's execution, the Queen is disqualified from purposeful procedures by typical womanly wavering between her feelings and her reputation with its bearing on the welfare of the state. In this respect, Swinburne's portrait therefore hardly violates the boundaries of conventional femininity. As far as the actual relationship with Chastelard is concerned, on the other hand, his Mary has transgressive elements in that she is clearly passionately attracted to the Frenchman, which sometimes gets the better of her especially when she visits him in prison: "What if we lay and let them take us fast, / Lips grasping lips? I dare do anything" (144). Chastelard, however, does not seem to recognise these feelings in her, as immediately before his death, he - apparently sincerely - supports her assertion that she never encouraged him. He even swears to the Scottish lords that she is "stainless toward all men" (146). Still more interestingly, he is convinced from the very beginning of the play that his love of Mary will mean death for him but he does not seem to hold her responsible for this. The metaphors of a deadly "sea-witch" (63) or "Venus" (128) he associates with her turn the fatal consequences of her beauty from a conscious decision on her part into an innate quality which she herself is powerless to change; as he prognosticates, "though you would, / You shall not spare one [man who loves her]; all will die of you" (142). Chastelard's view thus approaches the femme fatale image of the Scottish Queen in accordance with established critical opinions on Swinburne's female characters, but it seems to shift responsibility from the individual to some higher force. This, however, does not appear to preclude retribution directed at the human being herself: Mary's lady in waiting Mary Beaton, who loved Chastelard dearly, feels sure that "if I live then shall I see one day / When God will smite her lying harlot's mouth" (153) to punish the Queen for her lover's death.

Wills's 1874 play differs from the other two works in the way it relates to the genre system of the time. Nineteenth-century British drama was characterised by the opposition between an abundance of theatrical activity and the consensus in critical circles about the poor quality of these products. Playwrights were thus forced to decide whether to opt for popular or literary success, as the two were mutually exclusive. Whereas the indication "tragedy" shows a clear orientation towards "high art" in the previous two examples, which for Swinburne even included opposing performances of his works, Wills's drama was submitted to the Lord Chamberlain for inspection, licensed for production and successfully performed at the Princess's Theatre from February 1874 as Mary Queen o' Scots; or, The Catholic Queen and the Protestant Reformer.

| The Princess's Theatre | Programme | |

|  |

Despite its use of verse structure, this work can thus be designated a popular play, whose focus on dramatic confrontations, suspense and plot rather than character development demonstrates that it in the first place aims at providing entertainment for the audience.

This different orientation seems to go together with a new perspective on the protagonist: Mary Stuart's passion for Chastelard is presented much more openly than in Swinburne's drama, and she herself recognises its illicit nature: "Must not - perhaps 'tis why I crave to do it" (f. 8). When Chastelard emphasises her irresistible fascination (f. 12), this attraction therefore does not appear to originate beyond her control as in Swinburne's image; the Queen seems to know what she is doing and can even be seen to play with Chastelard in some scenes (ff. 2, 8). This confident handling of her effect on men becomes still more obvious in the second strand of the plot which confronts Marie with the Protestant reformer John Knox.1 Knowing his hatred of her and the danger it could entail to her position in Scotland, she cleverly uses her womanly charms to draw her enemy over to her side,2 so that she can then even call upon him to oppose Chastelard's execution.

The Queen of this drama thus personifies all fears about the darker female side by combining independent activity, specifically in the public realm, with conscious and self-determined sexual passion. Putting such a character on stage in nineteenth-century Britain meant using the power of the theatre with a very transgressive effect. Wills let the audience experience not only a marginalised social existence but a contradiction in terms: According to the received gender definitions of the period, the protagonist's actions placed her outside the honorary category of 'woman', while on the other hand her bodily presence on stage induced both male and female spectators to perceive her and respond to her as such. Marie Stuart reinforces this impact by allowing the audience to follow the thoughts of the unruly female, and her declarations of love to Chastelard are given a certain poetic beauty and dignity that make one feel for her. Even more importantly, the play shows her as deeply religious and willing to defend her Catholic faith against John Knox, thus mixing positive qualities with the characteristics of the female anti-image, especially when in the final scene Marie declares her love to Chastelard more or less in public and immediately afterwards defies Knox by finding comfort at the foot of the crucifix:

This portrait threatens the basic opposition in Victorian gender mythology, which has the uncanny implication that - inversely - it might indeed be possible for a 'good woman' to have certain (hidden) wicked traits. It is thus striking that such an image of the Queen can be found in a play meant and officially approved for performance and that contemporary reviewers unanimously stressed the good quality of the work and were only worried about whether the actors were able to render it adequately on stage.

Reviews

The Athenaeum, no. 2418 (28 Feb. 1874)

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 28 Feb. 1874

The Illustrated London News, 28 Feb. 1874

The Illustrated London News, 7 March 1874

The Illustrated London News, 14 March 1874

2. Mary Stuart and David Rizzio

A great number of nineteenth-century British plays focus on the period in which the Rizzio affair developed, but interestingly enough most of them do not address the question whether or not the Queen had an adulterous relationship with him. As the title indicates, James Redding Ware's drama Bothwell of 1871 is interested in this issue only in so far as Mary's attitude to Bothwell is affected by her public humiliation through Rizzio's murder and her husband's involvement in this incident. The same is true of a play with a rather different generic label, James Wimsett Boulding's 1873 historical tragedy Mary Queen of Scots, where the Queen is already close to Bothwell when she is suspected of unfaithfulness with Ritzio (sic) and hardly bothers to deny this charge as she wants to concentrate on planning her revenge against her husband (15). In M. Quinn's 1884 tragedy, which presents the whole of Mary Stuart's life in a total of 47 pages, the Rizzio affair appears as one illustration among many that, as the Queen herself recognises, her "feeble woman's hand" is "powerless to sway the sceptre in these turbulent times"; "[t]he task is beyond womanhood" (14-15). Again, the question of Mary's sexual purity or guilt does not play a role.

Works that treat her relationship with Rizzio in greater detail tend to find her innocent: Just as Terrell's David Rizzio, William Sotheby's 1814 tragedy The Death of Darnley shows the Queen as a helpless woman lost among the cunning enemies at her court, this time with Bothwell as the key schemer. In both dramas, the Italian secretary is set up as Mary's only friend for whom she clearly feels nothing but the most virtuous affection. In the 1814 tragedy, she explicitly states that he has become really dear to her only after his death when she began to recognise his role as "a guardian saint" in her life (64), while in Terrell's work, Rizzio does love the Queen but can only devote his life to assisting her knowing his feelings will never be requited. Thus, although Rizzio is murdered because of his attachment to Mary, the two plays emphasise that this is not the fault of her attraction but of the malevolent lords who pursue the Queen and all who are close to her.

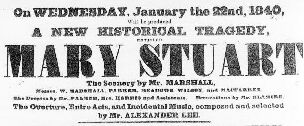

An equally victimised woman is the protagonist of James Haynes's historical tragedy Mary Stuart, which was successfully put on at the Drury Lane theatre from 22 January 1840.3 The evil machinations at court in this case originate with Ruthven, whose "fierce grandeur" constituted the chief attraction of the Rizzio material for Haynes ("Advertisement", 5). For the first performances, the part of Ruthven accordingly went to the star actor Macready, who overshadowed the female lead Mrs. Warner already on the playbill:

Just as in the other two plays, Haynes's Mary is the proverbial domestic woman displaced from her sphere whose ideal softness is repeatedly used against her and makes her unable to hold her own in the public realm. This aspect is foregrounded by the plate on the frontispiece of the 1886 Dicks' Standard Plays edition of the drama where a determined Ruthven in full armour intrudes into Mary's chamber, so that the futility of her feeble attempt to shield Rizzio becomes manifest:4

Haynes's portrait, however, differs slightly from the other two tragedies as far as the nature of the relationship with Rizzio is concerned. As the "advertisement" explains, Haynes considered it impossible to evade "Mary's attachment to her favourite" (as would have been necessary in order to keep the conventionally prescribed image of femininity intact), because that would have meant "suppressing the only circumstance, that could palliate, or indeed account for the sanguinary act [Rizzio's murder]" (6). Interestingly enough, it is thus the author's focus on a male protagonist that makes him blur ideological boundaries with regard to the female character. At the same time, however, Haynes senses that "the greatest danger" (6) is involved in combining model feminine characteristics with sexual impurity and therefore opts for a compromise. While his Rizzio loves Mary and she seems to reciprocate his affection (73), she does not respond openly to him and both of them feel a higher influence ruling their lives: Rizzio vows, "whate'er thou art, / That in mysterious thraldom hold'st my soul [i.e. it is not Mary Stuart as a person]; / I'm thine" (47), and the Queen feels that "[t]here is an envious malice in the stars, / That will not let me smile, but I must weep for 't" (72). As in Swinburne's Chastelard, however, the shift away from individual responsibility does not preclude retribution; while she is sure that she has acted "[l]ightly, not guiltily", Haynes's Mary is equally convinced that this is "hell's device / To plunge it's [sic] victim into hopeless crime" (97), i.e. into a state which calls for retributive justice. In terms of social gender mythology, this combination makes doubly sure that the threat to the prescribed ideal of femininity is kept minimal - the character herself did not infringe social standards but these norms are asserted again just in case by her anticipated punishment.

The second work in Swinburne's Mary Stuart trilogy, Bothwell of 1874, is equally reticent with regard to the Rizzio affair. The author cannot leave it out completely because of its relevance for the Queen's attitude to Bothwell, and convinced as he is of her superior intelligence and ability (see Swinburne 1905e: 212, 237; 1905d: 247, 256), he cannot represent her as innocent either, as that would have logically entailed making her the victim of court intrigues she did not see through. Instead of dramatising the relationship between the Queen and Rizzio, however, Swinburne confines himself to one piece of reported evidence - Darnley has found the secretary in his wife's room en déshabillé - and keeps the actual dialogues between the apparent lovers perfectly within the bounds of propriety. The reader is not allowed to witness any more than s/he would be told about the fall of a female human being in the "real" world and is "spared" observing transgressive actions in progress.

Plays that focus on Mary Stuart's relationship with David Rizzio thus show an overall continuity throughout the nineteenth century in both famous and more or less obscure works. Their preference is clearly for the figure of the innocent victim outside her proper sphere, which fits in very well with social concepts of what 'woman' should be like. Divergent images only seem to appear when absolutely necessary and are toned down as far as possible.

3. Mary Stuart, Bothwell and the murder of Darnley

This period of the Queen's life, which can be interpreted as involving her in both sexual and criminal guilt, provides the plot for the greatest number of nineteenth-century Mary Stuart plays in Britain. Apart from a few almost inadvertent hints, all of these works support the basic opposition between the social ideal and the anti-image by portraying the character either as guilty of all possible transgressions or as completely innocent. The analysis can therefore proceed from the same fundamental distinction.

The first group of plays absolve the Queen of Scots from both charges and include some works that are already familiar from conveying a similar image with respect to the other two accusations. In keeping with her role in the Rizzio affair, Sotheby's Mary is a model wife who forgives her husband's part in the murder of her secretary and wants to protect him when she feels his life might be threatened by the nobles of her court. Typically, she comes too late and falls to the ground, wishing for death - a final scene that makes her feminine powerlessness against her opponent Bothwell as graphic as possible. In Quinn's tragedy, the Darnley conspiracy appears as part of the Queen's memories at a later stage of her life when she laments that her "accomplished" husband was "torn from" her "through the machinations of [the] evil men" surrounding her (28).

The follow-up of Terrell's David Rizzio, Bothwell, then contains an interesting disjunction between the representation of Mary Stuart in the preface and in the play itself. In the plot of the drama, the Queen and Bothwell are so far from entertaining the "guilty attachment" (81) ascribed to them in the preface that Bothwell still repeatedly declares his love for his wife. Similarly, Mary's historical reference to David Rizzio's assassination immediately before Darnley's murder, which has often been used to demonstrate her familiarity with his impending fate, is given to Bothwell in the play and is only answered by her with the vaguest of premonitions that something might happen to avenge Rizzio (124) - certainly not the secure "knowledge" attributed to the character of the Queen in the preface. One can only conclude that the author fell short of his avowed intention to represent a guilty female because - as expounded in the same preface (81) - he believed the historical Mary to be innocent of the charges brought against her.

In The Tragic Mary, which Edith Cooper and Katherine Bradley published in 1890 under the pen name of Michael Field (see the review in The Spectator as an example of the mixed contemporary response to this work), the protagonist is an almost equally stereotypical 'good woman', even though female authorship combined with the preface's declared impartiality (vi) might lead one to expect a less conventional portrait.5 Mary Stuart is shown to be far more interested in her sewing than in affairs of the state, especially when this domestic occupation is undertaken to please her husband. She is beloved by all the women of her court including Lady Bothwell, who voluntarily sets her husband free when she believes this will make her sovereign happy.6 Although the Queen indeed realises uncomfortably at one point during Darnley's illness that she likes Bothwell's attentions, she is at the same time so far from any transgressive passion for him that she only agrees to marry him after he has more or less held her prisoner for seven days and she can only act like someone in deep sleep (202). In case Mary's involuntary response to Bothwell's wooing should be considered a lapse from virtue, the two authors take great care to introduce the motif of the overruling power of fate.7 After prognosticating in the first moments of the drama that the two of them will get married even though she is now banishing him, Bothwell later on tells the Queen, "We were one / Before the stars were broken to their spheres" (179). The relationship thus does not develop because of the protagonist's individual characteristics but is imposed on her according to the plan of an outside force, either as a test of her endurance set by God or as the work of malevolent fate. When Mary Stuart claims near the end of the play that she has never "[w]orn mask to God; before Him I could lie / As a white effigy, and let Him probe / Through my soul" (258), this profession of continuous religiosity consequently seems to be a faithful rendering of her subjective experience of the inevitable process. It only deepens the reader's sympathy for her and has none of the transgressive force of the final scene in Wills's play. As to criminal responsibility, the murder plot is clearly planned and carried out by Bothwell, Lethington and Morton without the Queen's knowledge in this drama; indeed, Darnley is killed just when she has got over his participation in the assassination of her secretary. This, however, does not prevent the model of femininity from feeling guilty momentarily because she "besought God's pity on [Rizzio's] soul" and "a reticence, / A strange dissatisfaction" remained in her heart even though she had (dutifully) forgiven her husband (144) - self-reproaches which only serve to highlight her complete dissociation from all genuine offences.

Works representing Mary Stuart as guilty of both sexual and criminal transgressions form the second group. Most cautiously, the historical drama Mary Stewart of 1801, which the Scot James Grahame specifically designated "a popular play" (161), refers to the murder only in the Queen's memories when she is trying to regain power in Scotland after escaping from Lochleven Castle. Troubled as she is by an apparition of her late husband, she only admits to having had knowledge of the planned assassination before it was committed and not having tried hard enough to dissuade Bothwell from it. Similarly, Mary clearly loves Bothwell in this play but they do not meet in the period selected by the playwright and - as a kind of safety valve - she is herself ashamed of her feelings: "Even to myself I will not own I love / A murderer - the murderer of my husband" (39). Standards of feminine behaviour are thus re-affirmed at the same time as they are threatened by the actions of the individual. In addition, Grahame's protagonist repeatedly invokes the malice of fate working against her (112, 142, 159), which can be taken to diminish her personal responsibility to some extent.

Boulding's historical tragedy is more daring in presenting an energetic Queen fired by insatiable ambition and so apt at playing the political game that she succeeds in outwitting the Scottish lords by turning her husband Darnley into her own puppet rather than theirs: "No man shall pull again / The strings which Mary has within her grasp" (35). When Bothwell offers to manage her revenge for her, she cleverly refrains from giving an explicit command. She only tells him to "remove / This adder [Darnley] from [her] path" in whichever way he likes and offers him her hand and heart in return (49). A bit further on, the play makes it clear that she is well-aware of the plan eventually adopted by Bothwell and does nothing to prevent it, on the contrary: "methinks / Rather than it should not be done I'd put / My own hand to it" (52). At exactly this point, however, the portrait of a transgressive Mary Stuart is given a certain didactic twist, which is - paradoxically - connected with her second offence. Boulding's Queen is strongly attracted to Bothwell and does not shy away from recognising the true nature of these feelings: "What would I give for the untainted joy / Of the young bride, [...] / By lust unblighted" (59, my emphasis). This avowal of sexual passion clearly places her outside the category of 'woman' in social terms. Within the play, however, it at the same time puts an end to her self-confidence and ambition, so that she concludes, "My own revenge / Could not so move me. Nothing but your love" (52), and is worried about the loss of her reign in the end only because she fears Bothwell might not be interested in her any more after that. Even though she is still far removed from the gentle submissiveness of 'woman' in terms of gender mythology and indeed will never be able to get back to that status, her rapid shift to obedience and dependence once she has found her master shows just how instinctively this behaviour is adopted by all members of the female sex. A socially prescribed gender role is thus "naturalised" in the typical manner of mythology and ideology described by Roland Barthes (1993: 129-131) and Louis Althusser (1971: 161) respectively.

Swinburne's Bothwell takes a few more (relatively small) steps towards the direct confrontation of the audience with female evil. Again, Mary Stuart is proves herself transgressively energetic and courageous in making Darnley aid her escape after Rizzio's murder, and in the first half of the play her illicit affair with Bothwell is foregrounded by love scenes which far surpass Boulding's in length and intensity. This rather more daring portrait is again followed by a change in the protagonist; she suddenly seems listless and gives herself up completely to Bothwell's will. With Swinburne, however, this development carries a different (though none the less conservative) ideological message, as the Queen's new behaviour clearly does not come "naturally" but is imposed on her: Maitland relates how Mary was forcefully abducted by Bothwell when out riding and - almost like Michael Field's protagonist - subdued to a "doglike" state (vol. III, 76). As her faithful follower Melville describes, she looked very unhappy at the ensuing marriage ceremony, while Bothwell appeared triumphant: "now / I think would one of them to free herself / Give the right hand she hath given him" (vol. III, 89). The play thus has transgressive passion bring about its own swift punishment, which re-affirms the prescriptive social standards of gendered behaviour. As regards the murder plot, Swinburne also goes further than Boulding: His Queen plays an active role in the plan by dissembling to Darnley to make him believe he is safe, and she does so successfully, even though - as she expounds in a lengthy message to Bothwell - the part is hateful to her and she only takes it on for his sake: "But I remit me to my master's will / In all things wholly" (vol. II, 377). Tellingly, it is Mary rather than Bothwell in this play who reminds Darnley of Rizzio's death shortly before the murder (vol. II, 431; cf. Terrell's Bothwell), i.e. she is given a fair share of criminal responsibility, so that the portrait painted of her differs from Chastelard. When Darnley recounts a dream of his about a siren luring sailors away from the safe route and into death, it seems as if Swinburne had tried to take up the central image of the earlier play. The Queen's involvement in the assassination is, however, too obvious here for the concept of fatality to preclude individual guilt, especially as the motif is at the same time less prominent than in Chastelard. The reassuring familiarity of established rules comes in only once in the murder plot: While Mary Stuart prepares for her part, she automatically concentrates on small household details like curtains which social mythology considered appropriate for every member of the female sex and which are indeed described as such in the play (vol. II, 407). As in Boulding's tragedy, prescribed gender characteristics are thus ideologically naturalised.

Three plays from outside the realm of tragedy can be seen to remove the "safety valves" that still protect the audience to a certain degree with Swinburne: Ware's Bothwell, William D.S. Moncrieff's Mary Queen of Scots of 1872, which he calls a "historical drama" with reference to Dr Samuel Johnson in order to escape the genre conventions of both tragedy and comedy, and John Watts de Peyster's American Bothwell (1884) omit both the element of absolving fatality and the subjection of the Queen to Bothwell. Ware and Moncrieff have Mary Stuart express her weariness of state affairs, but it quickly becomes clear that what the protagonist is really tired of is her marriage to the cowardly Darnley: She immediately becomes a proud Queen again when passion enters her life in the character of Bothwell - exactly the opposite effect from Boulding and Swinburne's tragedies. In the two non-tragic works, Bothwell is trying to gain ruling power in the state through Mary, so that it would have been very easy to present her as the victim of a scheming man parallel to her role in the tragedies by Terrell and Haynes. Ware and Moncrieff, by contrast, stress the equal status of the Queen and Bothwell in their relationship and, by implication, also their equal shares of criminal responsibility. Ware's protagonist inverts the usual feminine expression of allegiance to highlight their mutual dependence: "Bothwell, thy life is mine. / We live, or fall together" (48, my emphasis), while Moncrieff shows Mary Stuart as having her own way with regard to the murder plot. Whereas Bothwell wants her to agree to the plan more or less publicly together with the Scottish lords, she recognises the detrimental effects such a procedure would have on her relations with the rulers of England and France and orders Bothwell to prepare a secret bond with the lords' signatures. With political acumen that far surpasses her lover's and proves her weariness of power games to have been only a very passing one, she then remembers to make Bothwell keep a duplicate of the incriminating bond, which she uses against the lords towards the end of the play. The Queen's personal responsibility is also foregrounded when Moncrieff has her quote the image of the fatal siren - but in this case not in order to describe her own impact on the men around her but to illustrate the allure of crime and its inescapable consequences for those involved in it. Both playwrights moreover round off the transgressive portrait by intensifying Mary's energy and independence compared with Swinburne. Ware's Queen is so far removed from wifely submissiveness that she tells Darnley not to "forget that thou art not / The king. The queen's husband now, and nothing more", and she even strikes him on the shoulder when she surprises him with masked women (41). Interestingly enough, the publisher seems to have avoided a visual representation of these unfeminine traits in the printed text: the plate on the frontispiece shows Mary shocked at the duel between Bothwell and Douglas but does not include the turning point a few moments later when she purposefully intervenes to protect her lover (45). Moncrieff's play emphasises the physical side of unwomanly activity when his protagonist comfortably rides twenty miles to see Bothwell - a feat from which Swinburne's Mary falls severely ill. As Wills's Marie Stuart, these two works thus endow the Queen with all the traits of the female anti-image without any counterbalancing elements to reassure the audience, while at the same time making her the central female character. Her sex is therefore as continuously obvious as her infringements of the code of behaviour prescribed for the feminine gender.

To conclude the panorama of representations of Mary Stuart and Bothwell the analysis will now turn briefly to the American example cited above. John Watts de Peyster claims that his historical drama is a completely accurate rendering of facts apart from one minor exception (9), thus demonstrating - as already the title of one of his historical accounts of the Queen's life indicates (de Peyster 1883) - how vehemently the admissibility of different versions and the close relationship between them had to be denied in nineteenth-century America as well as in Britain. The play itself goes still further than Ware and Moncrieff's portraits: Mary Stuart eagerly absorbs all details of the murder plot, and when she meets Bothwell and the conspirators immediately before the assassination, he finds her pulse "strong, full and regular" - to which she replies, "So holds my purpose" (35). The Queen's passion is intensified in her numerous declarations of love to Bothwell, which dissociate her completely from the prescribed womanly modesty and reticence, and the story of Mary's abduction by Bothwell is turned into a clever strategy on her part to make the Lords allow her to become his wife officially, which she has already been "a twelvemonth in very deed" (51). Apart from making the Queen's criminal and sexual transgressions as explicit as possible, de Peyster also allows her to be even more active than in the most daring British plays: She not only rides to see Bothwell but lets herself down from a window thirty feet high and takes a sword and pistols with her (65), thus contrasting sharply with Swinburne's Mary, who cannot wear Chastelard's sword, and with the conviction of Quinn's protagonist that her only weapons are embroidery needles (25). At the same time, the illustrations in the printed text are again much more conventional: de Peyster reproduces an engraving taken from a sixteenth-century picture by Frederico Zucchero (after 14; cf. de Peyster 1883) and a portrait of Mary Stuart from the Hermitage Palace, St. Petersburg (71), both of which show a dignified but apparently not very energetic Queen.

On the whole, representations of Mary's relationship with Bothwell and her role in the murder of Darnley thus show an interesting polarisation according to dramatic genre, which expands the result reached with regard to the Chastelard affair: Tragedies show a marked preference for either absolving her of all charges or - if they opt for a guilty protagonist - reassuring the audience by curbing personal responsibility or re-affirming social standards at the same time as they are being infringed by the individual. Dramas with a more popular appeal, on the other hand, do not seem to be interested in the version of an innocent Mary but focus on characteristics excluded from the accepted gender type. Even though the plays analysed in this section do not threaten the basic distinction between 'women' and "other" females by mixing the respective traits, accumulating all possible kinds of female evil and confronting the audience with them directly nevertheless has an enormous transgressive force. This genre division can be used to account for the low profile of Mary Stuart's possible affair with David Rizzio in nineteenth-century British drama: The plays that concentrate on this period of her life are all tragedies and therefore shy away from conveying an image of female guilt. Interestingly enough, the distinction according to dramatic genres seems to remain in force throughout the whole of the nineteenth century, and it also does not seem to vary according to whether a play was written to be performed, i.e. to meet the scrutiny of theatrical censorship, or to be read. One can thus conclude tentatively that the nineteenth-century popular imagination seems to have been fascinated with the female anti-image which was only allowed an implicit presence in official gender mythology. On second thoughts, this result does not seem too surprising: The vicarious indulgence in transgression generally permits the audience to enter forbidden territory and enjoy a momentary superiority over established rules. On stage, but also on the page, a guilty female moreover allowed nineteenth-century male addressees to experience sexual attraction otherwise only available outside the bonds of respectable society, while women could share fantasies of female power that offered them a brief respite from the restrictions of their official gender role. Despite its relative obviousness, this background seems to have remained hidden from society's scrutiny in nineteenth-century Britain, as quite apart from licensing for performance, almost all of the popular dramas analysed here were published, often in established theatrical series. It will perhaps be easier to address this apparent paradox after an analysis of how the plays deal with the final phase of Mary Stuart's life and bring their own plot to a conclusion.

4. Ending Mary Stuart's life (story)

When one briefly recalls the basic genre laws of tragedy, it becomes clear why Mary Stuart's biography was so popular with nineteenth-century British dramatists working in this field. After all, the tragic protagonist is usually placed in a situation where he or she can only take wrong decisions, so that a life story leading to an execution is an obvious choice. The "pity and fear" evoked in the audience are heightened when this ending descends upon a relatively innocent character, who is then given the chance to undergo an internal development. From the tragedies analysed above, this ideal type of plot is realised most fully in Quinn's work where the subdued Mary grows to die a heroic death in the last few scenes. Two other tragedies focus specifically on the last phase of the Queen's life to be able to represent such a process in greater detail: In October 1880, Lewis Wingfield's Mary Stuart gave the star actress Madame Helena Modjeska the possibility of excelling in the role at the Royal Court Theatre.

| Review: The Illustrated London News 9 Oct. 1880 | Review: The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News 16 Oct. 1880 |  |

Even more than the theatrical reviews of her performance, illustrations highlight the majestic dignity of her presence on stage as Mary Stuart.

|  |  |  |

Wingfield's play is a faithful rendering of Schiller's Maria Stuart down to the level of phrasing and - as the reviewer of The Athenaeum notes - tries to make the German work succeed in London at last by adapting it to the requirements of the British stage.8 Interestingly enough, this also means leaving out the Queen's confession of her part in the murder of Darnley and her sinful passion for Bothwell in Act V, Scene 7. Mary Queen of Scots, performed at the Theatre Royal, Richmond in December 1894, was written by Robert Hely Thompson under the pseudonym of Robert Blake in order to "do battle for [Mary Stuart's] reputation", which the author perceived to be endangered especially by Swinburne's trilogy (4). In this work, the Queen is as innocent as Wingfield's and dies just as courageously: when she goes to her death, "[a]ll present instinctively rise and uncover" (54). Both dramas are moreover linked by a common element of fatality (Wingfield, 1880: f. 137; Blake, 1884: 15) that can be considered to distinguish nineteenth-century British tragedy from tragedy in general which tends to reject such obvious intrusions of fate; indeed, the respective passage from Wingfield's play is added compared with Schiller. Tragic fatality foregrounds the inevitability of the protagonist's destiny, and it is thus clear that although it reduces or even cancels out individual responsibility for transgressions, this will not preclude the "unhappy" ending. This almost paradoxical effect is most obvious in Swinburne's trilogy. By repeatedly voicing her trust in retributive justice, Mary Beaton gradually begins to personify the Queen's impending punishment in Chastelard. Disregarding historical facts, Swinburne has this attendant stay with Mary Stuart and accompany her to England, where in the last part of the trilogy (Mary Stuart) Mary Beaton sends a slanderous letter to the Queen of England which her mistress had once written but afterwards meant to be destroyed. This communication reaches Elizabeth when she seems about to pardon Mary and makes her sign the death warrant immediately. In the play, the Queen of Scots is thus punished for the death of Chastelard where the motif of absolving fatality is much stronger than for instance with regard to Darnley's murder. This stresses that with a guilty protagonist as well as with an innocent one, the focus is on the sense of fatal inevitability and not on a just penalty commensurate with the offence.

Despite the suitability of Mary Stuart's execution as the most graphic fatal ending possible, some of the tragedies discussed prefer to conclude at different points. Haynes's Mary faints after Rizzio's murder, Sotheby's collapses when her beloved Darnley is assassinated; in the last moments of Terrell's Bothwell, the Queen is about to be imprisoned at Lochleven Castle, and Boulding and Michael Field's works end when the execution has almost but not quite been decided upon. In all these cases, however, the ending conveys an atmosphere of complete hopeless and finality, which is put into words by the Queen of Terrell's Bothwell: "Then farewell life and empire! all is lost, / When once I enter its [Lochleven's] ill-omened walls" (140, my emphasis). Even though the death warrant has not yet been signed with Boulding and Field, Mary is surrounded by enemies, and the audience's knowledge of her historical fate will hardly permit them to entertain any hopes for her. It is thus possible to say that - shying away from the representation of an actual execution on stage or on the page - these tragedies opt for an equivalent state of death-in-life as the end of the life story. Interestingly enough, this procedure is adopted both by tragedies with a blameless protagonist and by those presenting a guilty Queen, which again shows that the emphasis is not on just punishment but on the sense of an inescapable fate. With a culpable Mary Stuart, this strategy moreover makes sure that the fatal conclusion of the drama does not evoke unsuitable emotions in the audience with regard to the evil female, as might have happened with a violent death and its obvious potential for causing sympathy or admiration respectively.

The endings of popular nineteenth-century plays, by contrast, on the whole distinguish sharply between guilt and innocence. This becomes especially graphic when comparing the last scenes in Grahame, Ware and Moncrieff with William Murray's Mary Queen of Scots; or, The Escape from Loch Leven, an adaptation of Guilbert de Pixérécourt's French dramatisation9 of Sir Walter Scott's The Abbot, which was first performed at Edinburgh in October 1825 and subsequently revived at the Olympic (1831) and Drury Lane Theatres (1850).10 All of the plays conclude at Lochleven Castle, and for Grahame and Moncrieff's Queens the final moments clearly bring about the end of their lives as rulers. The former is separated from the last attendant still left to her from better days, while the latter is forced by the Scottish lords to sign a deed of resignation "and throws away her crown" (111). Ware's drama ends with Mary's escape from Lochleven, which, however, conveys a similar feeling of dejection and loss: It takes place immediately after the Queen has been made to agree to her abdication under threat of physical violence, and the plan is nearly ruined by the appearance of Bothwell in an advanced state of mental decay. Mary then falls into the boat prepared for her, while he throws himself into the water. For the female protagonists of these plays the conclusions thus hold the prospect of a death-in-life state similar to that of the tragic Queens treated above. In contrast to the indiscriminate imposition of this fate in tragedy, however, these three characters are all guilty of criminal and sexual transgressions. Murray's work, on the other hand, shows Mary Stuart innocently imprisoned in the Castle by evil jailers and assisted by only a few faithful friends. Throughout, the audience is on her side as she actively works for her own escape, which is carried out successfully in the final moments of the play and brings with it a feeling of relief and triumph for the spectators. Despite the historical facts of the Queen's life, the ending thus cannot be other than "happy" for a good character in British popular drama of the nineteenth century, and in order to achieve this impression, the representation simply terminates at a convenient point. The guilty heroine, on the other hand, has to come to grief even if the same historical period is selected. This basic genre law of individual accountability means that a sense of fatality is generally not part of these works. When it does play a role - as in Grahame's drama - it is very obviously secondary to the judgement of the main character according to her actions and therefore does not entail an inevitable catastrophe. As it mitigates her personal responsibility for transgressions, it can even diminish the punishment accordingly, so that Grahame's Queen is not forced to give up her reign officially. Henry Roxby Beverly's dramatisation of Scott's Abbot, which was staged at the Theatre of Variety, Tottenham Street in September 1820, illustrates this aspect from the opposite point of view: The play follows the novel very closely and consequently includes passages where an innocent Mary Stuart laments her own "fatal charm" (60). This untypical element has tellingly disappeared both in Murray's drama and in his French model, but even with Beverly, it does not interfere with treatment of the protagonist according to her individual merits, i.e. the blameless woman escapes from her unjust imprisonment at Lochleven in the end.

All in all, the popular nineteenth-century British plays analysed here thus fit in with fundamental genre characteristics of 'melodrama' as they have for instance been described by Michael R. Booth (1965: 15) and Johann N. Schmidt (1986: 153-154): The genre proceeds from an absolute opposition between 'good' and 'evil', and these moral positions are represented by clearly recognisable character types. The struggle between the two sides is the moving force of the plot, which is without fail brought to a "happy" ending. This convention is synonymous to a triumph of virtue in melodrama, i.e. the 'good' characters are "happy" in the end, whereas the villains suffer the punishment they have brought onto themselves by offences for which they are personally responsible. In nineteenth-century Britain, audiences had internalised this pattern to such a degree that they could not only recognise the character types immediately but also had the secure knowledge that virtue would win again in the end. This assured return to moral standards may be the reason why popular drama was able to focus on the threatening female anti-image which social mythology could only acknowledge implicitly and why this practice even seems to have escaped the scrutiny of theatrical censors. At the same time the framework of the audience's emotional security helps to explain why the popular plays discussed above on the whole seem to be able to keep the sentence of the guilty Queen conspicuously light: de Peyster's work - typically the play with the most wicked protagonist - is the only one that includes her execution. Interestingly enough, this penalty is not even represented in detail but only appears in a final image of Mary with her head on the block (81), so that just retribution seems to have turned into a token punishment designated to reassure the audience and absolve them from all feelings of shame for having indulged in the fascination of female evil throughout the play.

The conventions of melodrama can also be used to account for other ways in which popular plays presented more daring female portraits than tragedies in nineteenth-century Britain. Although works of this genre did not necessarily have to subject a guilty female to capital punishment, there does not seem to have been any need either to avoid such a representation for fear of evoking inappropriate emotions; the overall opposition of moral values was apparently perceived as so stable that it could not be endangered. Thus, Albany Wallace's historical drama The Death of Mary, Queen of Scots of 1827 and the 1837 historical play Mary, Queen of Scots by Thomas Francklin 1837 both focus on the last phase of Mary Stuart's life like Wingfield and Blake's tragedies but work with a guilty protagonist: In Wallace's drama, criminal responsibility and sexual passion are attributed to her even by her friends (14-16), while Francklin has her understand her execution as just retribution for her affair with Bothwell and all the offences it involved (87). This, however, does not prevent the character from dying a courageous death in both plays which can hardly have failed to arouse admiration in the audience.

The two works moreover include an even more dangerous element by presenting Mary Stuart's insistence on dying as a Catholic as a genuine expression of deep religiosity (Wallace, 1827: 140; Francklin, 1837: 90) rather than the act of protest as which it in the first place appears in Swinburne's Mary Stuart. Thus, they give positive qualities to an embodiment of the anti-image and thereby undermine the most basic opposition of nineteenth-century gender mythology, as was already noted above with regard to Wills's representation of the Chastelard affair. The full transgressive impact of his portrait of the Queen now becomes clear in comparison: Expressions of religious belief and sexual passion stand side by side here rather than being assigned to different parts of the drama as with Wallace and Francklin, and Wills's Marie does not even suffer any punishment at all but is last seen deriving comfort from prayer. The fact that such images seem to have escaped notice in the nineteenth century may - slightly speculatively - be explained by a kind of "optical illusion" fostered by genre conventions. Nineteenth-century British melodrama was specifically produced to affect and entertain a popular audience. In contrast to abstract definitions of the genre, its opposition between 'good' and 'evil' was thus extended to the realm of audience response, i.e. the "sense of wholeness" Robert Bechtold Heilman attributes to the dramatis personae of melodrama in general included the wholeness of "appeal" in the nineteenth-century which is bracketed off in Heilman's description (1973: 54). A character presented as a 'good' one was therefore automatically perceived as a focal point for audience identification, and this convention may sometimes have precluded the recognition of exactly which traits came together in this particular figure. A suitable example is the phenomenon of the active melodrama heroine, whose existence is often denied in critical literature but confirmed by even a cursory perusal of popular nineteenth-century plays. Of the works analysed here, Murray's melodrama contains an active Mary Stuart who is at the same time shown to be 'good' by well-established dramatic conventions for signifying high moral quality: She feels Providence assisting her deliverance and has a relationship of mutual trust with her servant Catherine (25, 26). The infringement of standards represented by female activity thus no longer seemed threatening to contemporary spectators and its fascination could be indulged in without fear, to which the successful productions and revivals of the play testify.11 The censors were apparently convinced that no danger could proceed from this 'good' heroine - though from an outside perspective it is of course clear that such an audience response to transgression only increases the danger to established principles.

As regards a guilty Mary Stuart with deep religious convictions, familiarity with the established character outlines of melodrama may have induced the guardians of propriety to respond to the two theatrical types invoked in the different sections Wallace and Francklin's works as two distinct persons. Still more importantly, it now becomes a little clearer how the subversive potential of Wills's protagonist could go unnoticed in the nineteenth century: According to the genre laws of melodrama, she is cast as a 'good' heroine by the plot structure, as she triumphantly fights off the persecutions of her enemies and defends her faith while the spectators are made to follow the action from her perspective. Although contemporary audiences could thus enjoy the allure of unfeminine sexuality to the full, they were at the same time protected from consciously recognising the violation of norms involved. The anonymous reviewer of The Era provides abundant evidence for this effect when he calls the "general tone" of the play "charmingly pure and graceful" (my emphasis) and takes great care to dissociate Wills's Mary from Swinburne's relatively transgressive portrait in Chastelard:

On the whole, the comparative analysis of how the Queen of Scots is portrayed in nineteenth-century British drama has shown that melodrama, a genre often denigrated for its stereotypes and lack of innovative tendencies by contemporary and modern critics alike, can be much more daring in its choice of female protagonists than the accepted dramatic form of tragedy. Indeed, it seems to be the same well-worn conventions that both cause the critics' aversion and open up the genre towards images of female transgression, so that - paradoxically - the established preference for character types can be seen to have assisted the dissemination of transgressively differentiated and complex female dramatic images.

References

1 See the description of their first encounter given by the reviewer of The Athenaeum:

In the second act Knox appears. He bars Mary's entrance into the city, bidding her remove from her breast the cross she wears. Though urged by Murray and others to consent to this demand, Mary refuses. In the end her dignity triumphs over all obstacles, and she passes in front of the reformer, who has not before met with such an antagonist. (no. 2418 [28 February 1874], 302)

2 See the perspective on this process given in The Era:

So successfully does she use her power that the stern Reformer relents, and - though unwillingly - the mob retires at his request. Then Mary exerts her utmost influence over Knox himself, who struggles hard to resist her, but eventually yields. It is quite amusing to hear the grim Iconoclast wrestling with his own weakness in such phrases as "Get thee behind me, Satan," "John Knox, thy place is in the pulpit." He tells her that "she is not simple but strong - that there is nothing secret or sacred against a woman's white hand - no honour so well tempered that the flash of a woman's eye will not blunt it, no faith so fixed that it cannot be shaken by a woman's voice." (vol. 36, no. 1849 (1 March 1874), 11)

3 See The Theatrical Journal of 25 January 1840 (no. 6) and The Theatrical Observer; and Daily Bills of the Play of 1 February 1840 (no. 5652). "Drury Lane: The new Tragedy drew an excellent house yesterday evening."

4 Apart from the plate, this edition refers the reader to The Monastery and The Abbot by Sir Walter Scott for detailed descriptions of the characters' costume (2). The following illustrations made for The Abbot by D. Chamberlain (Scott 1831) can therefore give us some idea of how the publisher John Dicks meant Mary Stuart to appear in Haynes's play.

| '"Where is your colleague, my lord?"' | 'They both kneeled down before her.' | '"Not there - not there - these walls will I never enter more!"' |

|  |  |

5 See also The Athenaeum, no. 3282 (20 September 1890), 395:

The Mary Stuart of Michael Field answers to the hackneyed description of woman by Virgil, or that given of her own sex by Rosalind. She comes under the spell of Bothwell, whose brutal passion for her seems equally compounded of love and of hate, and she meets him in varying moods of repugnance and surrender. To extract, however, an intelligible theory of her character from her disjointed phraseology and her general extravagance of speech is a task sufficiently puzzling to the masculine intellect.

6 All of these relationships with women are obvious signs of the Queen's moral goodness in a nineteenth-century context. Together with the fact that the men at her court generally attempt (and manage) to subdue Mary Stuart, they have led Jayne Elizabeth Lewis to read the drama as "an allegory of lesbian desire" (1998: 196-197).

7 As noted in The Athenaeum's plot summary: "Bothwell has from the first a gloomy presage of coming events worthy of a Highland seer" (395).

8 For an example of how critics tended to respond to an unadapted rendering of Maria Stuart see an unattributed review (in the files of the Theatre Museum, London) of the translation staged at The Theatre Royal, Haymarket in May 1876.

9 The "mélodrame" L'Evasion de Marie Stuart (1822).

10 At the Edinburgh Theatre, the title role was acted with great success by the author's sister, Mrs. Henry Siddons (s. Macleod (n.d.), 329). In January 1831, Madame Vestris opened the Royal Olympic Theatre with this work, billing it (see playbill) as an "entirely New Historical Burletta" and foregrounding the star appearance of Miss Maria Foote as Mary Stuart. The play was then revived at the Drury Lane Theatre in March 1850 with Miss Laura Addison as the Queen of Scots. It was announced as an "Interesting Drama" for the "first time at this theatre". A contemporary engraving gives some idea of Laura Addison in the role, even though it - probably erroneously - considers her to be performing Schiller's tragedy.

| Miss Maria Foote |

Miss Laura Addison |

11 See fn. 10. The play was also revived in the provinces. The characters' names in the anonymous "new Historical Drama" Mary, Queen of Scotland put on at the New Theatre, Bridgnorth in January 1832, for instance, clearly reveal it to be a version of Murray's work adapted to the smaller company of a provincial theatre (see the playbills in the John Johnson Collection of The Bodleian Library, Oxford: Bridgnorth III.C.177, 177a and 180).