Chapter X:

The Search for Atomic Age Division

Since we cannot equal our

potential enemies on a man, for

man basis, we must give

our soldiers the means of increasing their effective firepower and we

must create an organization to control it.

Col. Stanley N. Lonning 1

After the Korean War the

Eisenhower administration adopted a military posture that emphasized

nuclear capability through air power rather than ground combat. Three

considerations dictated this change: limited resources, a worldwide

commitment to contain communism, and the desire to reduce defense

spending. Given the declining number of ground combat troops, the Army

fielded fewer divisions, but because the possibility of nuclear war

remained, Army leaders wanted to devise units that could fight and

survive on a nuclear as well as on a conventional battlefield. The

divisions developed by the Army for the two combat environments were

smaller than in the past, and they were authorized weapons and equipment

still under development and not yet in the inventory. The newly designed

divisions, however, staked out a role for the Army on the atomic

battlefield, which justified appeals for funds to develop new weapons.

Some Army planners thought a

general war would be too costly to wage by conventional means because

the Communist bloc could field more men and resources than the United

States and its allies. Firepower appeared to be the answer for

overcoming the enemy. Ever since the United States dropped the first

atomic bomb in 1945, American military planners had pondered the use of

nuclear weapons on the battlefield. The Army, however, was hampered in

its effort to understand the effects of tactical nuclear weapons by the

lack of data. Studies suggested that nuclear weapons could be used much

like conventional artillery. To achieve the aim of increased firepower

with decreased manpower, the Army began to take a closer look at that

proposition in the early 1950s.2

As had happened between World

Wars I and II, the new divisional studies began with the infantry

regiment. Army Field Forces initiated the studies in 1952,

[263]

when it asked the Infantry

School to examine both infantry and airborne infantry regiments. Four

goals were to guide the effort: elimination of nonfighters; expansion

and more effective use of firepower; simplification and improved

organization and control; and a reduction in the size of the regiment.

Army Field Forces dropped the last goal when it decided austerity should

begin in service and support units before being applied to infantry and

airborne infantry regiments. Both regiments were to be alike except for

the number of antitank weapons.3

The infantry regiment

recommended by the Infantry School consisted of three rifle battalions,

a headquarters and headquarters company, a service company, an antitank

company, and a weapons company armed with .50-caliber machine guns.

Removed from the regiment were the medical, heavy mortar, and tank

companies. Assets of the tank company were transferred to the division

and those of the heavy mortar company to the division artillery; instead

of the medical company, medical personnel were assigned directly to the

infantry battalions. The study proposed merging the heavy weapons

company of each infantry battalion with the battalion headquarters

company, except for the heavy .50-caliber machine guns, which were to be

integrated into each battalion's three rifle companies. Additional

automatic rifles were placed in the battalions, and more communication

personnel were assigned throughout the regiment.4

Maj. Gen. Robert N. Young,

Commandant of the Infantry School, had many reservations about the

proposed changes and believed that thorough field testing was needed to

evaluate them. As a result, an underequipped and understrength 325th

Infantry, an element of the 82d Airborne Division, began testing the

organization in May 1953 and completed the evaluation in September. The

results indicated that the proposed regimental organization was less

effective than the one then being used in Korea.5

In the meantime, the Tactical

Department of the Infantry School had also begun work on a new type of

infantry division. The redesign effort also sought to eliminate

nonfighters and to increase firepower as well as to simplify the

organization and improve control at the divisional level by using task

force organizations similar to those in the armored division. A fixed

organization such as an infantry regiment, the studies noted, forced the

commander to base his operational plans on the organization rather than

on the mission. Task force structures would permit him to organize his

forces to accomplish a broader variety of missions. The division that

evolved consisted of three brigade headquarters, nine infantry

battalions, two armored battalions, division artillery, and combat and

combat service support. The brigade headquarters elements had no

permanently assigned combat or support units. No reduction resulted in

the size of the division, which totaled 18,762 officers and enlisted

men.6

In April 1954 Army Chief of

Staff Ridgway shifted the emphasis of divisional studies. Under pressure

from the Defense Department for smaller units, he noted that divisions

had increased firepower and capabilities but were larger and less mobile

than their World War II counterparts. The possibility existed, he

[264]

General Ridgway

believed, to make divisions more

mobile, more flexible, and less vulnerable to atomic attack. To achieve

such goals he directed Army Field Forces to explore the following seven

objectives: (1) greater combat manpower ratios; (2) greater combat to

support unit ratios; (3) greater flexibility and greater mobility in

combat units; (4) maximum use of technological improvements; (5)

improvements in the Army's capability to sustain land combat; (6)

development of tactical doctrine to support the changes; and (7)

reorganization of the units by 1 January 1956.7

Although Army Field Forces

became the executive agent for the study, the Command and General Staff

College at Fort Leavenworth did much of the work required to meet the

tight schedule. The study centered on infantry and armored divisions

because of the similarity between infantry and airborne divisions.

Changes in the infantry division would automatically apply to major

aspects of the airborne division. By the fall of 1954 Army Field Forces

had developed the Atomic Field Army, or "ATFA-1," which it

believed could be organized in 1956.8

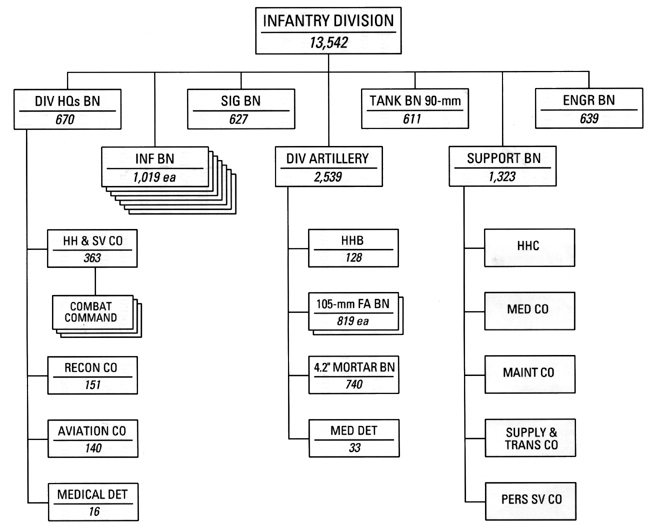

Under ATFA-1 infantry and

armored divisions were as similar as possible (Chart 26). The infantry

division included a separate headquarters battalion; signal, engineer,

and tank battalions; seven infantry battalions; division artillery; and

a support command. Within the division headquarters battalion were

aviation and reconnaissance companies, and within its headquarters and

service company were three combat command headquarters along with the

divisional staff. One 4.2-inch mortar and two 105-mm. howitzer

battalions made up the division artillery. The support command, a new

organization, comprised a battalion, which included medical,

maintenance, supply and transport, and personnel service companies.

Divisional elements lost all administrative functions except those

needed to maintain unit efficiency. Personnel for administration, mess,

and maintenance functions were concentrated in battalion headquarters

companies throughout. All staffs were minimal; the divisional G-1 and

G-4 functions were reduced to policy, planning, and coordinating

activities. Routine administrative and logistical matters were moved to

the support command. Infantry divisions, similar to armored divisions,

were to use task force organizations as situations required. Combat

command headquarters, the combat arms battalions, and the support units

were the building

[265]

Atomic Field Army Division, 30 September 1954

[266]

blocks. The strength of the

division stood at approximately 13,500 officers and enlisted men, a cut

of nearly 4,000 from the 1953 division.9

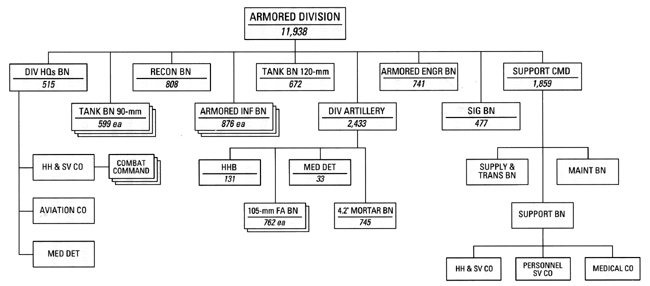

The armored division (Chart

27)

retained its task force structure. It consisted of headquarters, signal,

engineer, and reconnaissance battalions; three medium and three heavy

tank battalions; three armored infantry battalions; division artillery;

and a support command. The headquarters battalion was the same as in the

infantry division except for the reconnaissance unit, which was a

separate battalion. The artillery was also similar to that in the

infantry division, but the 105-mm. howitzers were self-propelled rather

than towed. A maintenance battalion and a supply and transport battalion

were assigned to the support command, but the division had no separate

medical or personnel service units, those functions being integrated

into the support battalion. The strength of the division was

approximately 12,000 officers and enlisted men, a drop of almost 2,700

soldiers.10

Within both divisions the

designers of the Atomic Field Army -1 introduced some significant changes. All

aircraft were gathered into an aviation company in the headquarters battalion. The

signal battalion, rather than maintaining communications along various axes,

provided a grid system that encompassed the entire division area. New FM (frequency

modulation) radios permitted that change. Antiaircraft guns were placed in

the field artillery battalions, and the military police functions were split

between the personnel service and the supply and

transport units in the support

commands. Separate antiaircraft artillery battalions and military police companies

disappeared from both divisions. Neither division fielded nuclear weapons, which

were instead located at the field army level.11

In February 1955 the 3d Infantry

Division in Exercise FOLLOW ME and the 1st Armored Division in Exercise

BLUE BOLT tried out these new organizations. The results of the infantry

division test showed that independent infantry battalions and the combat

commands added flexibility and that the support command provided an

acceptable base from which to improve logistical functions. Generally,

however, the division lacked the capability to wage sustained combat

operations. It needed more on-the-ground strength to execute normal

battlefield missions during an atomic war and larger reconnaissance

forces to cover the extended frontages and depths envisaged for the

nuclear battlefield. Additional antitank and artillery weapons were also

required. Staffs at division, combat command, and battalion levels were

too small to be fully effective. BLUE BOLT neither proved nor disproved

that the 1st Armored Division possessed less vulnerability to atomic

attacks. But the use of the same command posts for combat command

headquarters and tank battalions increased the division's vulnerability

to air attacks, as did the omission of the antiaircraft artillery

battalion. 12

Following the exercises Army

Field Forces revised the two organizations, and the 3d Infantry Division

and 1st Armored Division again tested them, this time in Operation

SAGEBRUSH, a joint Army and Air Force exercise. Both divisions retained

combat commands, but their staffs were increased to allow them to

conduct operations from separate command posts. The infantry division

had two tank

[267]

Atomic Field Army Armored Division, 30 September 1954

[268]

battalions and eight

four-company infantry battalions, while the armored division had one

heavy and three medium tank battalions and four infantry battalions of

four companies each. To improve command and control, separate division

headquarters, aviation, and administration companies replaced the

headquarters battalion. The division's artillery reverted to its

traditional structure of a headquarters and headquarters battery, a

medical detachment, and one 155-mm. and three 105-mm. howitzer

battalions with an antiaircraft artillery battery in each battalion. A

reconnaissance battalion, identical to the one in the armored division,

improved the "eyes and ears" of the infantry division.

Engineer resources were increased in both divisions, and a bridge

company was restored to the armored division. The support commands in

both organizations were restructured to consist of a headquarters and

headquarters company, a band, military police and medical companies, a

maintenance battalion, and a supply and transport unit. In the infantry

division the supply and transport unit remained a company, while in the

tank division it was a battalion. The signal battalion in both divisions

continued to furnish an area system of communications. These changes

increased the strength of the infantry division from 13,542 to 17,027

troops and the armored division from 11,930 to 13,971.13

Maj. Gen. George E. Lynch, the

"Marne" Division commander, and Maj. Gen. Robert L. Howze,

commanding "Old Ironsides," reached different conclusions

about the revised divisions. Lynch found that the infantry division

operated in much the same manner as a conventional division with an

improved logistical system. He nevertheless concluded that the Army

should return to the traditional- division organization with three

regimental combat teams, which, he believed, were as flexible as combat

commands. Furthermore, Lynch thought regimental organization fostered

morale; encouraged teamwork between subordinate and superior commanders,

as well as their staffs; provided knowledge about capabilities and

weaknesses of units and their leaders; and stimulated cooperative

working methods. Lynch's proposed changes raised the divisional strength

to 21,678 officers and enlisted men. Howze, on the other hand, found the

armored division generally acceptable. He suggested returning all mess

and second-echelon maintenance to the company level, converting the

medical unit to a battalion, forming headquarters and service companies

or batteries for battalions in all the arms, concentrating antiaircraft

resources into one battalion, and augmenting maintenance throughout the

division. Howze did not specify the strength of his proposed division,

but Lt. Gen. John H. Collier, Fourth Army commander, in whose area the

operation was conducted, reported on the test and recommended 15,819 of

all ranks.14

In 1956 the U.S. Continental

Army Command, which had replaced Army Field Forces, distributed revised

tables of organization for Atomic Field Army divisions throughout the

Army for review and comment. While controversies persisted, the command

noted that gains had been made in the infantry division's ability to

carry out a variety of missions and to protect itself against atomic

attack. The Atomic Field Army studies refrained from making any

revolutionary changes

[269]

General Taylor

in the armored division.

Recommended changes incorporated such desirable features as the area

system of communications, the administrative services company as a home

for special staffs and the replacement section, an aviation company for

more flexibility in the use of aircraft, and the new support command for

better logistical support.15

At this point Chief of Staff General Maxwell D. Taylor called a

halt. On 10 April 1956, he decided

the Army would not adopt the recommendations of the Atomic Field Army studies. They were not achieving

more austere divisions, but, in fact,

were recommending units that were

larger than the post World War II ones.

He

directed the Continental Army

Command to terminate all initiatives concerning the Atomic Field Army but to complete

reports for future reference.16

The Army's search for austere

units that could survive on both conventional and nuclear battlefields

thus appeared to have gone nowhere. Those who had tested or commented on

the Atomic Field Army divisions either disagreed with or had

misunderstood the overall objectives of Ridgway and the Army Staff. Maj.

Gen. Garrison H. Davidson, Commandant of the Command and General Staff

College, opposed a "lean" division because he thought it would

sacrifice training between the combat arms and services. He also thought

that such a division was inappropriate for use as a mobilization base.

The college, he noted, preferred "a very flexible outfit, which

could be beefed up or skinned down as necessary on deployment."17

Furthermore, those who evaluated

the divisions paid little heed to use of tactical atomic weapons. Over

250 simulated tests had been conducted in the SAGEBRUSH exercise. Taylor

concluded after the exercises that "we in the Army have a long way

to go before we understand the problems of using these weapons,"

noting that "we would have probably destroyed ourselves and all our

friends had we tossed atomic weapons about a real battlefield in the way

we did in this maneuver."18

In response to Ridgway's

directive in November 1954, the Army War College had begun work on a

study entitled "Doctrinal and Organizational Concepts for Atomic-Nonatomic

Army During the Period 1960-1970," which had the short title

[270]

101st Airborne Division simulates

an atomic bomb blast, Fort Campbell, Kentucky, 1957.

of PENTANA. Ridgway wanted the

study to outline broad doctrinal and organizational concepts applicable

to sustained ground combat on the Eurasian land mass during the period

1960-70. While the study was to make use of the maximum technological

developments, including nuclear weapons of all types, Ridgway also

desired that the Army retain a capability for conventional warfare.19

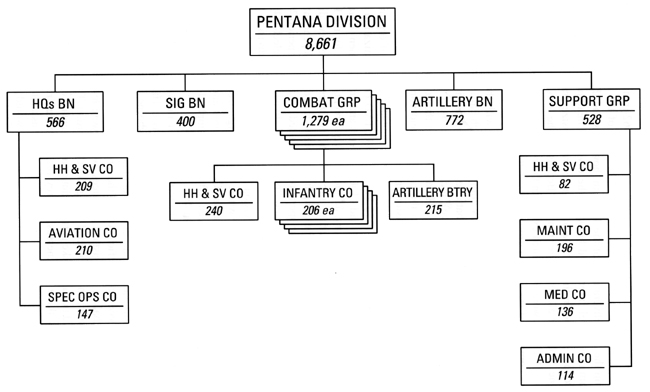

Completed in December 1955, the

Army War College study called for a completely air transportable

8,600man division to replace infantry, airborne, and armored divisions.

The new division was to be built around five small, self-sufficient

"battle groups" that would include their own artillery. The

battle groups were to meet the tactical requirements for dispersion of

forces, operations in depth, and increased flexibility and mobility on

the atomic battlefield. Organic division artillery, although meager,

included the Honest John, a surface-to-surface rocket with a nuclear

warhead. The division had minimal logistical and administrative support

and lacked tanks, antiaircraft artillery, engineer, and reconnaissance

units (Chart 28).20

Not surprisingly, many Army

leaders found the PENTANA division unacceptable. When General John E.

Dahlquist, commander of the Continental Army Command, forwarded the

study to Washington, he noted that the reaction of the arms and services

to the division was directly related to the impact of the proposal on

their strengths and missions. Those who perceived an increase in

responsibility endorsed the idea, those who saw no change acquiesced,

and those who discerned a diminution of strengths and responsibilities

violently opposed it. The Armor School objected to the lack of

divisional tanks, the Artillery School desired more conventional

artillery, and the Command and General Staff College questioned the

division's staying power. The most damning comment came from Chief of

Engineers Lt. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis, Jr., who considered the concept

"completely unacceptable intellectually and scientifically."21

Nevertheless, Chief of Staff

Taylor approved the PENTANA study on 1 June 1956 as a goal for future

research and development of new weapons, equipment, and organizations.

It was not an entirely new idea for him. As the commander of the Eighth

Army he had experimented with a division having five subordinate

elements in the Korean Army. In the meantime, the Army was to fill the

gap

[271]

Honest John rocket launcher

between what it had and what it

wanted by adopting modified versions of the concept, using new weapons

and equipment as they became available. He believed that until the goal

of a PENTANA division could be reached, the Army would continue to need

infantry, airborne, and armored divisions.22

Before Taylor approved the

PENTANA study, he had directed the reorganization of the airborne

division using a modification of the concept. He judged the existing

airborne division incapable of functioning effectively either in an

airborne role or in sustained ground combat. It could neither be divided

into balanced task forces nor be airlifted. Taylor suggested a division

of 10,000 or 12,000 men organized into five battle groups that fielded

nuclear weapons. Including such arms in the division, he believed, would

both stimulate their development and assist in developing doctrine for

their use.23

On 15 December 1955, the

Continental Army Command submitted a proposal for an airborne division

that incorporated features of both the PENTANA and ATFA studies. Each

one of its five battle groups would consist of four infantry companies;

a 4.2-inch mortar battery; and a headquarters and service company

comprising engineer, signal, supply, maintenance, reconnaissance,

assault weapons, and medical resources. A divisional support group made

up of a maintenance battalion and administrative, medical, and supply

and transport companies provided logistical services. The divisional

command and control battalion assets included the division headquarters,

a headquarters and service company, an aviation company, and a

reconnaissance troop. A signal battalion furnished a grid communication

system, and a small engineer battalion provided the resources needed to

construct an airstrip within forty-eight hours. The artillery fielded

three

[272]

PENTANA Division

[273]

105-mm. howitzer batteries

(eight pieces each) for direct support and one nuclear weapons battery,

equipped with two cumbersome 762-mm. Honest John rockets, for general

support. Planners sacrificed the range of the 155-mm. howitzers to gain

the air deliverability of the 105-mm. howitzers and their prime movers.

No command level intervened between the division headquarters and the

battle groups or between the battle groups and company-size units,

speeding response time. Staffs for all units were minimal. Because of

the lean nature of the division, mess facilities were eliminated except

in the medical company and the headquarters company of the support

group. Instead, the Continental Army Command recommended the attachment

of a food service company in garrison.24

Taylor approved the concept in

February 1956 with the following modifications: the addition of a fifth

infantry company to each battle group, an increase in the number of

105-mm. howitzer batteries from three to five (while reducing the number

of pieces from eight to five), inclusion of a band, and the elimination

of the attached food service company. He also wanted the administration

company moved from the support group to the command and control

battalion and the artillery group redesignated as division artillery.25

Following Taylor's guidance, the

command published tables of organization and equipment on 10 August 1956

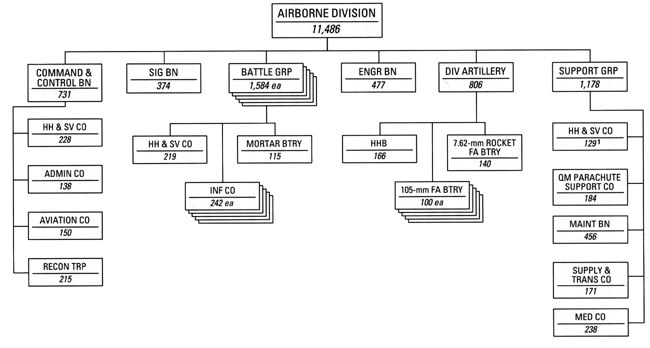

known as ROTAD (Reorganization of the Airborne Division). The division

had 11,486 officers and enlisted men (Chart 29), and, for the first time

in its history, all men and equipment, except for the Honest Johns,

could be carried on existing aircraft. The designers of the new division

thought that it was capable of operating from three to five days

independently, but it would need to be reinforced for operations that

lasted for a longer period.26

To test what Taylor called the

new "pentomic" 27

division, he selected his former unit, the

101st Airborne Division, then serving as a training division at Fort

Jackson. On 31 April 1956, the division moved without its personnel and

equipment to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where it was reorganized,

acquiring personnel from the 187th and 508th Regimental Combat Teams and

equipment from the 11th Airborne Division that had been left at Fort

Campbell after the unit had participated in the GYROSCOPE program.28

The "Screaming Eagles"

conducted a series of individual unit evaluations rather than one

divisional exercise. Lt. Gen. Thomas E Hickey, the test director, judged

the new division suitable for short-duration airborne assaults, with

improved prospects for survival and success during either an atomic or a

conventional war. However, he noted major deficiencies in the direct

support artillery-its short range and lack of lethality; in logistical

resources, which were less effective than in the triangular division;

and in the total strength of the division. The division was so austere

that it could not undertake garrison duties and maintain combat

readiness.29

To remedy these weaknesses,

Hickey recommended replacing the 105-mm. howitzers with 155-mm. pieces

except for parachute assaults. Instead of five howitzer batteries, he

proposed four. The larger howitzer would give the direct support

artillery the range he believed that the division required. Also, since

the fifth battle

[274]

Airborne Division (ROTAD), 10 August 1956

1 Includes the Division band.

[275]

group in the division was to be

held in reserve, he proposed deleting its direct support artillery

battery. Other recommendations included eliminating the support group

and reorganizing the logistical resources, except for maintenance

organized along functional lines, in a pre-Atomic Field Army

configuration. A 10 percent increase in divisional strength was

suggested, as well as an enlarged garrison complement wherever a

pentomic division was stationed. Hickey wished to move the

administration company to the rear because its functions did not require

the unit's presence in the forward area; he thought the infantry platoon

should be eliminated from the reconnaissance troop because it lacked the

mobility of the troop's other elements; and he wanted a military

intelligence detachment added to the division's headquarters battalion

to help with order of battle, photographic interpretation, and other G-2

duties. Finally, he advocated an increase in the grades of the

commanders of the rifle companies, mortar batteries, and howitzer

batteries to make their rank commensurate with the responsibilities

associated with independent actions required on the "pentomic

battlefield."30

The test findings and Hickey's

recommendations worked their way through the Continental Army Command.

Dahlquist agreed with most of Hickey's proposals except for the

artillery and support group. He believed that 105-mm. howitzers should

be retained as direct support weapons because they could be airlifted in

two helicopter loads or towed by 3/4-ton trucks. Rather than decreasing

the number of artillery batteries, he wanted the division to retain

five, each with six pieces. He opposed changes in the support group

because its structure had not been fully tested, and he felt that

Hickey's recommendation to eliminate it was premature.31

The Army Staff agreed with

Dahlquist's views regarding the number of artillery batteries but not on

increasing the number of pieces in each battery. No change in the

support group won approval, and the staff opposed the elimination of the

infantry platoon from the reconnaissance troop, the addition of the

military intelligence detachment, and alterations in the rank of company

and battery commanders. The Continental Army Command published tables of

organization for the pentomic airborne division reflecting the views of

the Army Staff in June 1958 without a change in unit's overall strength.

Both the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions adopted them by December.32

Shortly after the 101st Airborne

Division began testing ROTAD, Taylor directed the Continental Army

Command to develop a new infantry division along similar pentagonal

lines. It was to have five battle groups (a headquarters and service

company, one mortar battery, and four infantry companies each);

conventional and nuclear artillery; tank, signal, and engineer

battalions; a reconnaissance squadron with ground and air capabilities;

and trains. The trains, who commander was responsible for the activities

of the service troops in the rear area, were to include a transportation

battalion, an aviation company, and an administration company. The

transportation battalion was to have sufficient armored personnel

carriers to move an entire battle group at one time, and the aviation

company was to be placed in the trains for better supervision of its

maintenance. Taylor wanted to

[276]

optimize the span of control in

the division by giving each commander the maximum number of subordinate

elements that could be controlled effectively. He believed such a

division could be organized with 13,500 men of all ranks, a reduction of

nearly 4,000 from the 1955 infantry division.33

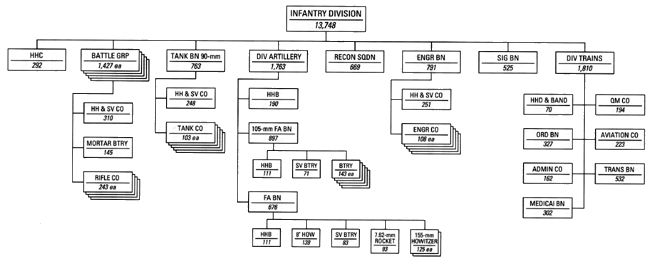

On 15 October 1956 the

Continental Army Command forwarded manning charts (Chart 30) for

"ROCID" (Reorganization of the Current Infantry Division) to

Washington. The planners followed Taylor's general guidance but

recommended a division slightly larger than expected. They provided the

tank and engineer battalions with five companies each and the division

artillery with two battalions-five batteries of 105-mm. howitzers in one

and an Honest John rocket, one 8-inch howitzer, and two 155-mm. howitzer

batteries in the other. Each 105-mm. howitzer battery fielded six pieces

and boasted of its own fire direction center, and each mortar battery in

the battle group had assigned liaison, fire direction, forward air

controller, and forward observer personnel. In addition to headquarters

and headquarters detachment and band, the division trains included

medical, ordnance, and transportation battalions and aviation,

administrative, and quartermaster companies.34

Taylor hesitated to adopt the

pentagonal structure for the armored division because he feared that

such a change would make the organization too large. Nevertheless, Lt.

Gen. Clyde Eddleman, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Military Operations,

instructed the Continental Army Command to modernize the division by

adding atomic weapons, increasing target acquisition capabilities, and

reducing the number of vehicles. To carry out his wishes, the command

added a reconnaissance and surveillance platoon to the reconnaissance

battalion, provided aircraft in the aviation company to support it, and

replaced the 155-mm. howitzers in one battery of the general support

battalion with 8-inch howitzers that could fire nuclear rounds. No

significant reduction in the number of vehicles took place because the

atomic and conventional battlefields required more transportation

resources than authorized in the existing division. A command and

control battalion that included administration and aviation companies

was added. To offset increases in the divisional elements, the command

eliminated the antiaircraft artillery battalion.35

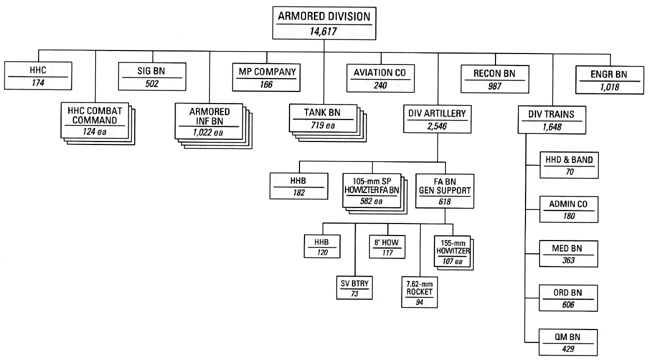

On 5 November 1956 the Army

Staff approved the pentomic armored division with some exceptions. The

staff directed the formation of separate divisional headquarters,

aviation, and administrative companies in place of the suggested command

and control battalion and moved the administration company to the

trains. The former 155-mm. howitzer battalion was reorganized as a

composite unit comprising an Honest John, an 8-inch howitzer, and two

155-mm. howitzer batteries. The Army published the "ROCAD"

(Reorganization of the Current Armored Division) tables reflecting these

changes in December 1956. They called for a division of 14,617 officers

and enlisted men (Chart 31), 34 fewer than included in the 1955

tables. The tank count stood at 360, of which 54 were armed with 75-mm.

guns and 306 with 90-mm. guns. All the medium tanks were in four tank

battalions.36

[277]

Infantry Division (ROCID), 21 December 1956

[278]

After the Continental Army

Command completed the tables of organization for infantry and armored

divisions, Taylor met with Army school commandants on 28 February 1957

to sell them on the pentomic reorganization of the Army. He noted that

the doctrine of massive retaliation ruled out nuclear war, but that the

chance existed that war might stem from unchecked local aggression or

error. The Army had to be prepared to prevent or stop a small war as

well as conduct a nuclear conflict. He believed that the new divisions,

although controversial, could meet both challenges.37

More important was what Taylor

did not say about the pentomic divisions and why the Army was adopting

them. The Army's budget called for unglamorous weapons and equipment

such as rifles, machine guns, and trucks, which had little appeal for

Congress or the nation. Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson earlier

had returned the Army's budget to Taylor, directing him to substitute

"newfangled" equipment that Congress would support.

The Army's literature soon

reported on such ideas as "convertiplanes," which combined the

advantages of rotary-wing and fixed-wing aircraft; one-man "flying

platforms"; and the adoption of pentomic divisions, which fielded

nuclear weapons. Later Taylor wrote, "nuclear weapons were the

going thing and, by including some in the division armament, the Army

staked out its claim to a share of the nuclear arsenal.." 38

When reorganizing Regular Army

infantry and armored divisions in 1957 under the pentomic structure,

several major changes were made in the force to accommodate a cut of

100,000 men and changing world conditions. In the Far East, the United

States agreed to withdraw all ground combat troops from Japan.

Subsequently the 1st Cavalry Division moved to Korea, where it replaced

the 24th Infantry Division. While the 7th Infantry Division remained in

Korea, the 24th was eventually reorganized in Germany to replace the

11th Airborne Division. Also in Germany, the 3d Infantry Division

replaced the 10th Infantry Division, which was returned to Fort Benning

as part of GYROSCOPE. With these changes U.S. Army, Europe, still

fielded five divisions, the 3d and 4th Armored Divisions and the 3d,

8th, and 24th Infantry Divisions. The European command also retained an

airborne capability by reorganizing two battle groups in the 24th

Infantry Division as airborne units. At Fort Benning, Georgia, the 2d

Infantry Division, which earlier had been reduced to zero strength,

replaced the 10th Infantry Division, which was inactivated. The 5th

Infantry Division was also inactivated at Fort Ord; the 1st Armored

Division, less its Combat Command A, was reduced to zero strength; and

the 25th Infantry Division was cut one battle group. When the game of

musical chairs with divisions was over, the Regular Army consisted of

fifteen divisions. In most cases only the division names and flags

moved, not the personnel and equipment. These changes in the divisional

designations reflected the desire of Army leaders to keep divisions with

outstand-

[279]

Armored Division (ROCAD),1956

[280]

ing histories on the active

rolls. Most soldiers, however, did not understand the rationale, and

unit morale suffered.39

As the Army reorganized and

shuffled divisions around the world, it adopted the Combat Arms

Regimental System (CARS) for infantry, artillery, cavalry, and armor.

During the ATFA and PENTANA studies a debate arose regarding unit

designations. Traditionally regiments were the basic branch element,

especially for the infantry, and their long histories had produced deep

traditions considered essential to unit esprit de corps. The new

divisional structure, replacing infantry regiments with anonymous battle

groups, threatened to destroy all these traditions. Secretary of the

Army Wilber M. Brucker settled the question on 24 January 1957 when he

approved the Combat Arms Regimental System. Although regiments would no

longer exist as tactical units except for armored cavalry, certain

distinguished regiments were to become "parent" organizations

for the combat arms. Under the new concept, the Department of the Army

assumed control of regimental headquarters, the repository for a unit's

lineage, honors, and traditions, and used elements of the regiments to

organize battle groups, battalions, squadrons, companies, batteries, and

troops, which shared in the history and honors of their parent units.40

When infantry regiments were

eliminated in divisions as tactical units, they were also eliminated as

nondivisional organizations. The Army replaced the nondivisional

regimental combat teams with separate, flexible combined arms

"brigades," shifting the concept of a brigade. Instead of

being composed of two or more regiments or battalions of the same arm or

service, the concept encompassed a combined arms unit equivalent to a

reinforced regiment. Initially only two brigades were formed. First was

the 2d Infantry Brigade, activated at Fort Devens on 14 February 1958 to

replace the 4th Regimental Combat Team. No tables of organization

existed for the unit, which at the time consisted of a headquarters, two

battle groups, one artillery battalion, a reconnaissance troop, two

engineer and two armor companies, and trains. The last element was an

adaptation of the trains of an infantry division and consisted of a

headquarters element and administration, ordnance, quartermaster, and

medical companies. A miniature division, the 2d Brigade had 4,188

officers and enlisted men commanded by a brigadier general. To support

the Infantry School at Fort Benning, the Third United States Army

organized the 1st Infantry Brigade on 25 July 1958. It contained two

battle groups; one artillery battalion (one Honest John, one 155-mm.

howitzer, and two 105-mm. howitzer batteries); armor, transportation,

and engineer companies; and signal and chemical platoons, but no trains.

A colonel commanded the 3,600 officers and enlisted men assigned to the

unit. 41

After completing the pentomic

reorganization in the Regular Army, the Continental Army Command

conducted further tests of the new organizations. In

[281]

general, such efforts elicited

favorable reports, finding the divisions to be adequate for atomic and

conventional warfare. In particular, the command noted the new infantry

division's flexibility, unity of command, mobility, and decisive combat

power in terms of nuclear firepower. The infantry division, however,

suffered from deficiencies in four areas-staying power, ground

surveillance, artillery support, and staff organization. To correct

these problems, the command made several recommendations: adding a fifth

rifle company and a radar section to each battle group; eliminating the

4.2-inch mortar as an artillery weapon (but retaining some in the

headquarters company of the battle group); reorganizing the artillery

into one divisional composite battalion (one Honest John and two 8-inch

howitzer batteries) and five 105/155-mm. howitzer battalions (two

self-propelled and three towed); and bolstering the aviation company

with an aircraft field maintenance element, an avionics repair team, and

approach control teams. More staff officers were essential, particularly

for the G-3 operation sections. The transportation battalion's truck

company was found to be inadequate, and officers in the field suggested

that all companies in the battalion be equipped with armored personnel

carriers.42

As in the development of the

pentomic airborne division, rank structures also came under scrutiny.

Because of the increased command responsibility, the Continental Army

Command recommended that the commander of the headquarters company of

the battle group be raised from a captain to a major and that commanders

of the smaller artillery battalions be reduced from lieutenant colonels

to majors. Compared to an infantry regiment, the new battle group lacked

billets for majors, a circumstance that would adversely affect the

career pattern of infantry officers.43

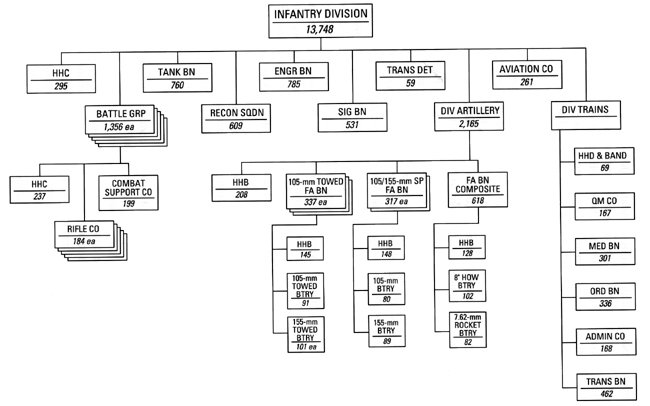

On 29 December 1958 Deputy Chief

of Staff for Military Operations Lt. Gen. James E. Moore approved the

recommendations for reorganizing the infantry division with some

changes. He rejected changes in the grades of the commanders of

artillery battalions and the headquarters company of the battle groups

and vetoed additional armored personnel carriers for the transportation

battalion. He dropped an 8-inch howitzer battery from the composite

artillery battalion, leaving it with only one 8-inch howitzer battery

and one Honest John battery, and split the headquarters company of the

battle group into two organizations, a headquarters company and a combat

support company. All tactical support, including the radar section and

the reconnaissance, heavy mortar, and assault weapons platoons, were to

be contained in the battle group's combat support company to achieve

improved command and control. A separate transportation detachment was

added to provide third-echelon aircraft maintenance. With this guidance

in hand, the Continental Army Command published new tables of

organization for the division, without a change in its overall

strength-13,748 of all ranks (Chart 32).44

For the armored division,

further tests led to a number of minor adjustments. These included

moving the reconnaissance and surveillance platoon in the recon-

[282]

Pentomic Infantry Division, 1 February 1960

[283]

naissance squadron to the

aviation company, providing a transportation aircraft maintenance

detachment to support the aviation company, and reorganizing the

reconnaissance squadron as in the infantry division. Observers also saw

the need for an alternate, or backup, divisional command post, a larger

staff for the artillery coordination center, and the establishment of a

radiological center to detect radioactive contaminates. Minor

alterations were also to be made in the service units to support these

new alignments. All changes in the armored division were made without

increasing its strength of 14,617.45

In 1959 and 1960 the Army placed

Regular Army infantry and armored divisions under the revised tables

that resulted from the field tests. Also, to meet a Department of

Defense manpower ceiling of 870,000, the Army Staff decided to eliminate

the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Carson, Colorado. The Fifth United

States Army reduced the division to zero strength and later inactivated

it, cutting the number of active Regular Army divisions to fourteen. In

Korea the Army continued to resort to the Korean Argumentation to U.S.

Army (KATUSA) program, begun during the Korean War, to keep the 1st

Cavalry Division and the 7th Infantry Division at full strength; each

division was assigned about 4,000 South Koreans.46

The Army Staff had delayed

reorganization of the reserves, but in 1959 it decided to realign

National Guard and Army Reserve divisions under pentomic structures. A

controversy immediately surfaced over the required number of reserve

divisions. Secretary of Defense Neil H. McElroy decided on 37 divisions,

27 National Guard and 10 Army Reserve. By 1 September 1959 the

twenty-one infantry and six armored divisions in the Guard had

reorganized, and one month later ten Army Reserve infantry divisions

completed their transition, but at a reduced strength. The eleventh

combat division, the 104th, in the Army Reserve was converted to

training, for a total of thirteen training divisions, all of which were

in the Army Reserve.47

Following the pattern

established by the regulars, the states eliminated nondivisional

regimental combat teams from the Guard and replaced them with separate

combined arms brigades. Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Arizona organized the

29th, 92d, and 258th Infantry Brigades, respectively. These units had

varying numbers of combat arms elements but lacked trains needed to

support independent operations.48

When reserve units began to

adopt pentomic configurations, the Continental Army Command developed

separate organizational tables for training divisions. These tables

permitted the Army Reserve to retain the existing authorization of three

general officers-the commander and two assistant commanders-and ensured

standardization of these noncombat divisions. Each training division

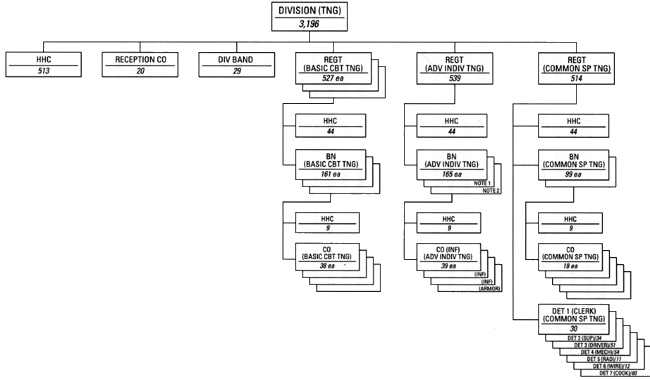

consisted of a headquarters and headquarters company, five regiments (an

advanced individual, a common specialist, and three basic combat

training regiments),49

a receiving company, and a band (Chart 33). Each

division in reserve status had about 3,100 of all ranks and on

mobilization would run a replacement training center capable of training

12,000 men. The continental armies reorganized the

[284]

Training Division, 1 April 1959

Note 1 2d Bn (Adv Indiv Tng) includes:

(AD Arty) (Adv Indiv Tng)

(FA) (Adv Indiv Tng)

2 (Engr) (Adv Indiv Tng)

Note 2 3d Bn (Adv Indiv Tng) includes:

(Cml) (Adv Indiv Tng)

(Ord) (Adv Indiv Tng)

(Med) (Adv Indiv Tng)

(MP) (Adv Indiv Tng)

[285]

training divisions in 1959, and

the adjutant general officially redesignated them as "divisions

(training)."50

One of the objectives of the

pentomic reorganization was to enable the units to absorb new equipment.

The M14 rifle, a 7.62-caliber rifle that could fire in semiautomatic or

automatic modes, replaced the vintage M1 rifle, the carbine, the

submachine gun, and the Browning automatic rifle; the 7.62-caliber M60

machine gun replaced the heavy water-cooled and light air-cooled

Browning .30caliber machine guns. These new weapons simplified

production; reduced spare parts, maintenance, and training time; and

used standard NATO cartridges, permitting greater compatibility with

Western European weapons. The diesel-powered M60 tank, armed with a

105-mm. gun, and the low silhouette, air-transportable M113 armored

personnel carrier also entered the Army's inventory. Work began on new

antiaircraft weapons, recoilless rifles, and 4.2-inch mortars, but most

did not become available for several more years.51

When the Army completed the

pentomic reorganization in 1960, it had 51 combat divisions in its three

components (14 in the Regular Army, 10 in the Army Reserve, and 27 in

the National Guard), 5 infantry brigades (2 in the Regular Army and 3 in

the Guard), and 1 Regular Army armored combat command. Although

divisions were organized for nuclear warfare, only a few were actually

ready for combat. Some Regular Army divisions continued to conduct their

own basic training courses to reduce costs and personnel, and Korean

nationals served in the divisions in Korea. Guard units ranged between

55 and 71 percent of their authorized strengths, while Army Reserve

organizations varied from 45 to 80 percent.52

In sum, as the Eisenhower

administration reduced the Army's budget from $16 billion to $9.3

billion between 1953 and 1960, the total force dropped to the lowest

number of divisions since the beginning of the Korean War. On the

surface, changing concepts of warfare during this period led the Army to

adopt pentomic divisions, structures that fell outside traditional

organizational practices. But whatever the concerns of Army leaders for

operating on a nuclear battlefield, Taylor, the primary force behind the

new divisions, clearly was using the pentomic concepts to get increases

in the military budget from political leaders who were less interested

in supporting more conventional military systems. Nevertheless, the

fertile ideas of this period resulted in new organizational concepts and

new equipment and weapon systems, all of which were to see further

development in the next two decades.

[286]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-