- President John F. Kennedy 1

- President John F. Kennedy ushered in the era of "flexible response" in 1961, deciding that the threat of a general nuclear war had become remote, but that the possibility of brush-fire wars had increased. To meet the varied challenges of the era, the Army soon abandoned pentomic structures and struck out in new directions. Eventually divisions with a standard divisional base and interchangeable maneuver elements-infantry, mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, and armor battalions-emerged as a means of tailoring units for service in diverse environments. The idea theoretically resulted in more flexible forces and divisions that took full advantage of new equipment, in particular new tanks, armored personnel carriers, and helicopters. International events delayed immediate reorganization, and when the Army was able to act, constraints on personnel and funds forced the adoption of many compromises in the structure of the divisions that emerged.

-

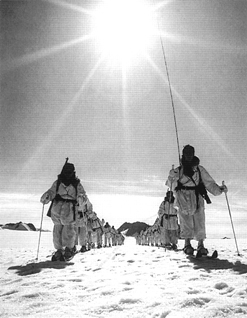

MOMAR-I - To move beyond the unrealistic PENTANA concept of a universal division, General Bruce C. Clarke, commander of the Continental Army Command, put his staff to work in early 1959 on a new organizational model, the "Modern Mobile Army 1965 (MOMAR-1)." Clarke, who had served as General Maxwell D. Taylor's deputy in Korea, believed the Army of the future had to be capable of operating effectively on both nuclear and nonnuclear battlefields anywhere in the world against a variety of threats. Its units had to be capable of fighting independently or semi-independently under a diverse set of geographical and climatic conditions. Furthermore, he believed that conventional firepower had to be increased and tactical mobility and maneuverability improved, primarily by using armor-protected vehicles and aircraft.2

- [291]

- The M60 and, below, M48 tanks

- [292]

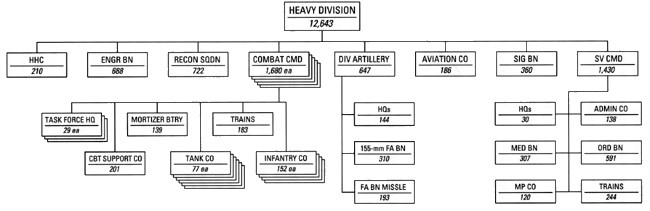

- When completed, MOMAR-1 called for heavy and medium divisions (Charts 34 and 35). Both types had five combat commands, but within the commands were three task force headquarters to which commanders could assign tank and infantry companies and elements of a train (support) company and "moritzer" battery. The proposed moritzer was to be a cross between a mortar and howitzer. Thus, the new models retained the flexible command structure of the armored division and foreshadowed the idea of "building blocks" around which to organize forces. Every man and every piece of equipment in both divisions was to be carried or mounted on vehicles.3

- War games indicated that medium and heavy MOMAR-1 divisions could not meet the Army's needs in many potential trouble spots throughout the world, and they were never field tested. In December 1960 the Vice Chief of Staff, General Clyde Eddleman, rejected the concept entirely. He noted that MOMAR-1 divisions lacked the simplicity, homogeneity, versatility, and flexibility that the Army needed to fulfill its worldwide responsibility in the coming decade.4

-

The Development of ROAD - General Eddleman set the Army on a new organizational course on 16 December 1960 when he directed General Herbert B. Powell, who had replaced Clarke as commander of the Continental Army Command, to develop divisions for the period 1961-65. The vice chief wanted the command to consider infantry, armored, and mechanized divisions. The heart of his mechanized division was to be armored infantry units that had the mobility and the survivability needed for the nuclear battlefield. But all divisions were to have both nuclear and conventional weapons, as well as any other new weapons or equipment that might become available by 1965. Because of the many areas for potential employment throughout the world, Eddleman suggested that divisions be tailored for different environments. However, since he still wanted to make the types of divisions as similar as possible, Eddleman instructed the planners to weigh the retention of battle groups or their replacement with infantry battalions in both infantry and airborne divisions. He questioned whether those divisions should have a combat command or a regimental command level between the division commander and the battalions as in the armored division. Furthermore, preliminary evidence suggested the possibility of interchanging battalion-size armor, mechanized infantry, infantry, and artillery units within the divisions. No set strengths were established for divisions, but Eddleman expected none to exceed 15,000 men.5

- Eddleman's instructions reflected many of the organizational ideas he had developed after leaving the position of deputy chief of staff for military operations in May 1958 and before returning to Washington as the vice chief of staff in November 1960. In the intervening period he served as commander of US. Army, Europe, and Seventh Army, becoming involved with the establishment of the West German Army. That army, unlike those of some NATO countries that had adopted

- [293]

- Medium Division (MOMAR), 1960

- [294]

- Heavy Division (MOMAR), 1960

- [295]

- General Eddleman

- pentagonal divisions, employed a building-block approach to organization. Rather than establishing permanent infantry and armored divisions, the Germans relied on infantry and armored brigades that would be formed into divisions tailored for specific missions. The German brigades, although fixed organizations, could also control additional battalions. To increase flexibility, elements of armor and mechanized infantry battalions could be interchanged to form combat teams heavy in infantry or armor.6

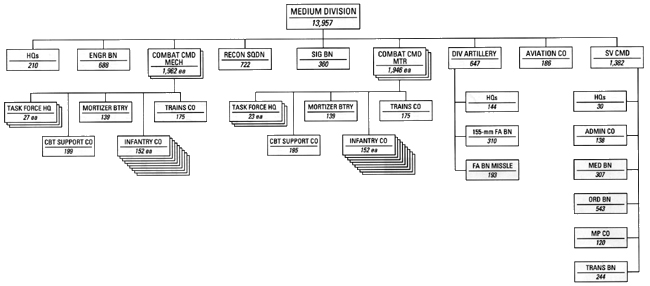

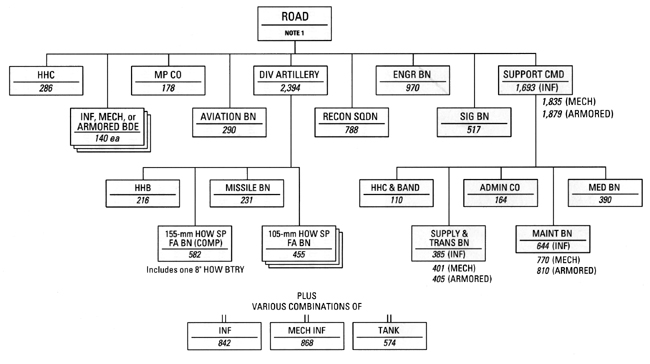

- In less than three months Powell submitted a study entitled "Reorganization Objective Army Divisions (1961-1965)," usually called ROAD, to the Army Chief of Staff, General George H. Decker. Unlike the PENTANA and MOMAR-I studies, ROAD did not address the general reorganization of the Army; it dealt only with infantry, mechanized infantry, and armored divisions. Using the armored division as a model, the study called for all three to have a common base to which commanders could assign varying numbers of "maneuver" (i.e., ground combat) elements-infantry, mechanized infantry, and tank battalions. The predominant maneuver element determined whether the division was classified as infantry, mechanized infantry, or armor.7

- The base for every ROAD division would consist of a headquarters element, which included the division

- commander and two assistant division commanders; three brigade headquarters; a military police company; aviation, engineer, and signal battalions; a reconnaissance squadron with an air and three ground troops; division artillery; and a support command. The division artillery included three 105mm. howitzer battalions, an Honest John rocket battalion, and a composite battalion (one 8-inch and three 155-mm. howitzer batteries). All artillery was self-propelled. The division artillery commander, however, was reduced from a brigadier general to a colonel. The support command embodied a headquarters and headquarters company, an administration company, a band, and medical, supply and transport, and maintenance battalions. Although structured alike in all divisions, the supply and transport and the maintenance battalions varied in strength and equipment to accommodate the missions of the divisions. The commander of the support command assumed responsibility for all divisional supply, maintenance, and medical services and the rear area activities, including security. Supply and maintenance

- [296]

- functions were to be provided at one-stop service points. Elements of the support command were designed so that they could be detached and sent to support task forces in independent or semi-independent operations. The brigade headquarters, like the combat commands in the existing armored division, were not to have permanently assigned units and were not to enter the administrative chain of command; instead, they were to function exclusively as command and control headquarters, supervising from two to five maneuver elements in tactical operations.8

- Responding to Eddleman's wishes, the designers of ROAD determined that an infantry battalion was more appropriate than a battle group as the main building block of the infantry division. Benefits of a battalion included a better span of control, simpler training procedures, greater dispersion on the battlefield, and more career opportunities for infantry officers. In the battle group, the commander's effective span of control was too great. He had so many diverse elements to supervise (infantry, artillery, engineer, medical, signal, reconnaissance, supply, and maintenance) that he found it difficult to manage the unit. A return to the infantry battalion would simplify command and control, logistics and maintenance, and also training. Given the need for dispersion on the battlefield, the study noted that 20 percent of the pentomic infantry division's combat strength was in each battle group. The loss of a single battle group in combat would be significant. With nine infantry battalions, the new division would lose only 11 percent of its battle strength if one of its battalions were hit by nuclear fire. In addition, many situations in combat required a greater variety of responses than the battle group could easily provide. Some tasks were too large for a company but too small for a battle group; others called for a force larger than one battle group but smaller than two. The smaller-size infantry battalions appeared to answer those needs. Finally, the battle group provided little opportunity for infantry officers to gain command experience. If the battle group were retained, only 5 percent of the Army's infantry lieutenant colonels would receive command assignments and only 4 percent of the majors would serve as second-in-command. Weighing all these aspects, the planners recommended that infantry battalions replace battle groups.9

- In an effort to provide maximum homogeneity, simplicity, and flexibility, the maneuver battalions were kept as similar as possible consistent with their individual roles. Each infantry, mechanized infantry, and armor battalion comprised a headquarters, three line companies, and a headquarters and service company. Similarity among the maneuver battalions extended to the reconnaissance platoons, which were the same in all battalions, and to the platoons in the reconnaissance squadrons. Given battalions of this nature, companies and platoons could be used to build task forces for specific operations with a minimum of turbulence. Taking advantage of the latest weapons, all infantry battalions and reconnaissance squadrons had two Davy Crocketts, low-yield nuclear weapons that were considered the "Sunday punch" of the ROAD divisions. Infantry and mechanized infantry battalions also had the new ENgin-Teleguide Anti-Char (ENTAC) missile, a French-designed antitank weapon.10

- [297]

- Davy Crockett rocket launcher

- With fixed bases and varying numbers and types of maneuver battalions, planners envisaged that divisions could be tailored in three ways. The first, "strategic tailoring," gave the Army Staff the opportunity to design units for a particular environment; the second, "internal tactical tailoring," allowed the division commander to build combat teams for specific missions; and the third, "external tactical tailoring," permitted army or corps commanders to alter divisions according to the circumstances. In the past, divisions had been adapted in all three ways, but ROAD made such tailoring easier at all levels.11

- On 4 April 1961 officers from the Continental Army Command and the Army Staff briefed Decker on the concept, and he approved it nine days later. He told Powell, however, that divisions were to be largely fixed organizations because the Army lacked the resources to maintain a pool of nondivisional maneuver battalions for intra- or inter-theater tailoring. In Decker's opinion, the interchangeable characteristics of the battalions were sufficient to provide tailoring within and among divisions without keeping extra units. He asked Powell only to consider substituting towed artillery for self-propelled artillery, eliminating the 155-mm. howitzers, and reorganizing the rocket battalion so that it would include both an Honest John rocket and two 8-inch howitzer batteries. The amount of organic transportation in the infantry battalion also seemed excessive, and Decker wanted reductions if possible. The study provided only two Davy Crocketts for each infantry battalion and reconnaissance squadron; Decker suggested adding a third, making one available for each line company or troop in those units. As a priority, Decker wanted doctrine and training literature to be quickly developed, particularly for the support command. Doctrine for the employment of nuclear weapons remained unclear.12

- Within a few months the Continental Army Command published draft tables for ROAD infantry, mechanized infantry, and armored divisions (Chart 36). They called for 105-mm. howitzers in the infantry division to be towed and a 30 percent reduction in the organic transportation of the infantry battalions. The 155mm./8-inch howitzer battalion remained as planned, but a new rocket battalion was designed consisting of a headquarters and service element and two Honest John batteries. Each infantry battalion and reconnaissance squadron had three, instead of two, Davy Crocketts. 13

- Before briefing Chief of Staff Decker on ROAD, Eddleman asked Powell's Continental Army Command to have available a concept for reorganizing the airborne division along similar lines. The vice chief of staff believed that ROAD could be modified to incorporate lighter equipment for such forces. For

- [298]

- ROAD Division Base, 1961

- Note 1 Strength will vary depending on the combination of maneuver elements assigned.

- [299]

- Little John rocket launcher

- example, the airborne division would not need as many infantry or tank battalions as other units, towed artillery could be substituted for self-propelled, the 8inch howitzer battery could be eliminated, and a lighter rocket could be used in place of the Honest John.14

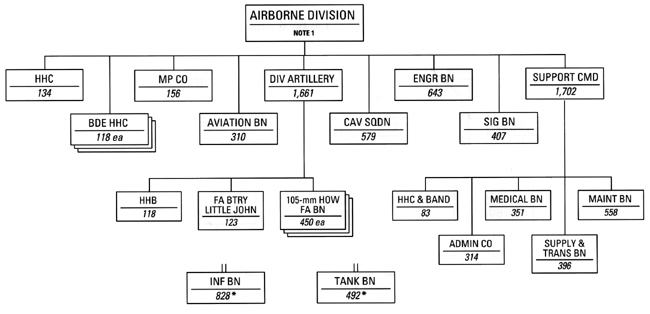

- After the approval of ROAD, the Continental Army Command quickly applied the concept to the airborne division. Its airborne study called for a division base similar to ROAD units. For the artillery, the 318-mm. Little John rocket replaced the larger Honest John, and two batteries of Little Johns along with a battery of 155-mm. howitzers formed a composite artillery battalion. They recommended deleting the bridge company from the ROAD engineer battalion and reducing the airborne division's reconnaissance squadron by one ground troop. The light tank battalion was to be equipped with new M551 Sheridans, armored reconnaissance airborne assault vehicles, but, pending their availability, the unit would employ 106-mm. recoilless rifles mounted on 1/4-ton trucks.15

- In September 1961 the Army Staff approved the concept in principle with minor modifications. The new 90-mm. self-propelled antitank guns (M56 SPATs) would replace the recoilless rifles, and the number of vehicles was cut throughout the division. When the tables (Chart 37) were published, the airborne division also lacked the composite artillery battalion because the 155-mm. howitzer was not air-transportable. Instead, the Little John rockets were organized into a two-battery battalion.16

- The doctrine of flexible response required combined arms units smaller than divisions, and the Continental Army Command responded by developing an air-

- [300]

- Airborne Division, 1961

- * Number and type of maneuver battalions may vary.

- Note 1 Strength will vary depending on the number and type of maneuver elements assigned.

- [301]

- Airborne Brigade, 1961

- * Number and type of maneuver battalions may vary.

- Note 1 Strength will vary depending on the combination of maneuvers elements assigned.

- [302]

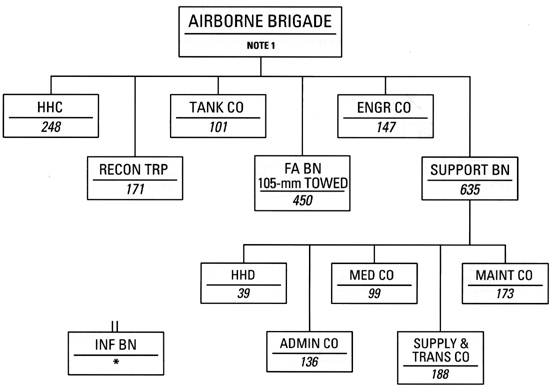

- borne brigade. Like divisions, the brigade had no fixed structure but consisted of a base, which could command and control from two to five maneuver battalions. The brigade base consisted of a headquarters company; a reconnaissance troop; light tank and engineer companies; a 105-mm. howitzer battalion; and a support battalion (Chart 38). Within the latter organization were administrative, medical, supply, transport, and maintenance resources that allowed the brigade to conduct independent operations. The brigade, however, had limitations, including inadequate air defense artillery and airlift resources. Its mobility on land was restricted by its limited number of organic vehicles. Nevertheless, the brigade met most of the Army's requirements for a small airborne combat team. At the Army Staffs direction, the idea was extended to armor, infantry, and mechanized infantry brigades. Since such units could operate independently or reinforce divisions, they promised to greatly increase the overall flexibility of the field army.17

- Powell suggested to Eddlemen during the early development of ROAD that if it were approved the Army should have a comprehensive information plan explaining the rationale for such a major reorganization. Both the military and the general public had to be reminded that organizations evolved in response to past experience and new equipment. Furthermore, political implications had to be considered. General Taylor, the primary advocate of pentomic divisions, then serving on the White House staff, might question the radical shift. Also, the reserve community might object to the turbulence so soon after completing the pentomic reorganization.18

- Powell's desire for a publicity plan received a boost when the new Kennedy administration, reacting to the worldwide struggle with communism, decided to improve the readiness of the nation's military forces. On 25 May 1961, President John F. Kennedy announced to a joint session of Congress that the Army's divisional forces would be modernized to increase conventional firepower, improve tactical mobility in any environment, and ensure flexibility. In addition, separate brigades would be organized to help meet direct or indirect threats throughout the world.19

-

ROAD Delayed - Kennedy's statement implied an immediate reorganization, but international events delayed changes. During the summer of 1961 relations between the Soviet Union and the United States deteriorated, particularly over the status of Berlin, and on 25 July the president asked Congress for funds to fill existing pentomic divisions and modernize their equipment. He also sought authority to order the reserves to a year of active duty. Congress agreed, and the Army postponed the ROAD reorganization.20

- To answer Soviet initiatives in Berlin, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara directed that the five divisions in Europe be brought to full table of organization strength and that the 3d, 8th, and 24th Infantry Divisions each be

- [303]

- Elements of the 32d Infantry Division train at Fort Lewis, Washington, during the Berlin crisis; below, pre-positioned equipment in Germany awaits the arrival of the 4th Armored Division in Operation Big Lift.

- [304]

- authorized an additional 1,000 troops. The troop increase permitted the complete mechanization of the divisions with additional armored personnel carriers. The readiness of the Strategic Army Force was increased in the United States and the training base was expanded, eliminating the basic training mission in combat divisions.21

- In the summer of 1961 Congress also authorized the Defense Department to order 250,000 reservists (individuals as well as those in units) to active duty for twelve months. The subsequent closing of the Berlin border on 13 August 1961 sparked another series of mobilization measures. In October the Army Reserve's 100th Division (Training) was ordered to active military duty to open the training center at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas. That same month the Kennedy administration approved the deployment of two additional combat divisions to the European command. Two National Guard divisions were federalized in October to replace the divisions programmed to be deployed from the strategic force, bringing the total number of divisions on active duty to sixteen. The 32d Infantry Division (Wisconsin) was sent to Fort Polk, Louisiana, and the 49th Armored Division (Texas) reported to Fort Hood, Texas. In all, 113,254 officers and enlisted men of the Army National Guard and Army Reserve were ordered into active military service.22

- During the crisis no division deployed to Germany, but during the next few months the Army took other steps to strengthen its forces in Europe. Measures included equipping the troops with new M14 rifles and M60 machine guns and accelerating production of M60 main battle tanks and M 113 armored personnel carriers, actions that permitted the Army to field those systems earlier than planned. To shorten the time required to move units to Europe, the Army positioned sufficient materiel in Germany to equip one armored division, one infantry division, and several nondivisional battalions. To maintain the equipment, personnel from the 2d Armored and 4th Infantry Divisions moved to Germany, but eventually permanent caretaker units replaced these men. Shortly after the equipment was placed in Germany, the Army launched Operation BIG LIFT, with units from the United States traveling to Europe and conducting exercises with the stockpiled equipment, a precursor of similar exercises that were soon to become a regular fixture in the Army.23

- The Army also increased combat readiness in other commands. It replaced the cumbersome Honest Johns with Little Johns in the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions and 4th and 25th Infantry Divisions, a step directed toward improving the ability to move these units by air. The 25th Infantry Division was brought to full strength in Hawaii, and the reinforced airborne battle group that had been sent to Okinawa in June 1960 was relieved from assignment to the division but remained in Okinawa. In Korea the strength of two divisions was also increased.24

- Following the call-up of the reserves for the Berlin crisis, Congress authorized a modest permanent increase in the strength of the Regular Army, and in January 1962 Secretary McNamara approved the activation of the first two

- [305]

- ROAD divisions, which were eventually to replace the two National Guard units in the strategic force. On 3 February the Fourth U.S. Army reorganized the 1st Armored Division, using its Combat Command A as its nucleus, at Fort Hood. The division became a mechanized infantry unit having four armor and six mechanized infantry battalions. Sixteen days later the Fifth U.S. Army reactivated the 5th Infantry Division (less its 2d Brigade and a tank battalion) at Fort Carson, Colorado, by absorbing the personnel of the training center there. The 2d Brigade, 5th Infantry Division, was activated at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, using the resources of the 2d Infantry Brigade, which was inactivated. The brigade continued to support reserve training In the First U.S. Army area, while one of the 5th Division's tank battalions stationed at Fort Irwin, California, supported the Combat Developments Command's test and evaluation programs. Stretched from coast to coast, the 5th Infantry Division had three infantry battalions at Fort Devens, one armor and six infantry battalions at Fort Carson, and one tank battalion at Fort Irwin.25

- When McNamara approved the activation of the two Regular Army divisions in early 1962, he decided to delay reorganization of the remainder of the Army until fiscal year 1964 because of the Berlin crisis. But events soon overtook that decision. For example, during the spring of 1962 Powell directed that all instruction at the Infantry School after 1 July reflect ROAD doctrine. Therefore, the Infantry School asked for permission to reorganize the 1st Infantry Brigade under a ROAD structure. Instead, the Army Staff decided to inactivate the pentomic-structured brigade and replace it with a new ROAD unit, the 197th Infantry Brigade, which resolved a unit designation issue.26

- The ROAD reorganization once again brought up the matter of unit designations. Divisional brigades had not appeared in the Army force structure since the demise of the old square division. Army leaders decided that two out of the three new brigade headquarters In each infantry division would inherit disbanded or inactivated infantry brigade headquarters associated with the former square divisions. With the designation 1st Infantry Brigade slated to return to the 1st Infantry Division when it converted to ROAD, the existing unit at Fort Benning required a new name. For it and other separate brigades, the staff selected infantry brigade numbers that had been associated with Organized Reserve divisions that were no longer in the force. For the new ROAD brigade at Fort Benning, Georgia, for example, the adjutant general on 1 August 1962 restored elements of the 99th Reconnaissance Troop, which thirty years earlier had been organized by consolidating infantry brigade headquarters and headquarters companies of the 99th Infantry Division, as Headquarters and Headquarters Companies, 197th and 198th Infantry Brigades. The following month the 197th Infantry Brigade was activated at Fort Benning. For the third brigade in each infantry division, the staff redesignated the division headquarters company, which had been disbanded during the pentomic reorganization, as a brigade headquarters. For example, the 3d Brigade, 5th Infantry Division,

- [306]

- perpetuated Headquarters Company, 5th Infantry Division, which had been inactivated in 1957. In the armored division, Combat Commands A, B, and C were redesignated as the 1St, 2d, and 3d Brigades.27

- When the Third U.S. Army activated the 197th Infantry Brigade at Fort Benning to support training at the Infantry Center, it consisted of a composite artillery battalion (105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzers and Honest Johns), an armor battalion, a mechanized infantry battalion, two infantry battalions, an engineer company, and a chemical platoon, but no support battalion. The strength of the brigade was approximately 3,500 men.28

- After the aborted Bay of Pigs invasion and rumors of Soviet assistance to Cuba, McNamara decided to

- bolster available Army forces in the Caribbean area. The Army replaced the battle group in the Canal Zone with the 193d Infantry Brigade, which was activated on 8 August 1962. Initially it consisted of only one infantry battalion and one airborne infantry battalion, but shortly after activation an artillery battery and an engineer company were added.29

- By mid-August 1962 the 1st Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions attained the approved readiness status for the strategic force, and the Army readjusted its divisions by releasing the reserve units three months early. Subsequently the National Guard's 32d Infantry Division and 49th Armored Division left federal service and reverted to state control, and the 100th Division (Training) also reverted to reserve status, closing the training center at Fort Chaffee.30

- In October 1962, less than three months after the 1stArmored Division had become part of the strategic force, the Army used it as part of an emergency assault force being assembled to counter the buildup of Soviet missiles in Cuba. For more immediate access to port facilities, the division moved from Fort Hood to Fort Stewart, Georgia, where it conducted a series of amphibious exercises. As tensions eased during the late fall, "Old Ironsides" returned to Fort Hood without conducting any active operations against Cuba.31

- When the Army put off reorganizing the remainder of the Regular Army divisions under ROAD until January 1963, the delay permitted the 1st Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions to evaluate the concept. General Decker reported to Secretary of the Army Cyrus R. Vance that "ROAD provides substantial improvements In command structure, organization flexibility, capability for sustained combat, tactical mobility (ground and air), balanced firepower (nuclear and nonnuclear), logistical support, and compatibility with Allied forces (particularly NATO)." 32 The chief of staff added that commanders of the 1st Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions had not identified any major problems that would require changes In the general concept.33

- Decker saw advantages and disadvantages In the pending ROAD reorganization. A comparison between the ROAD infantry and mechanized infantry divisions with the augmented pentomic infantry division showed some significant gains for the new organization. With only a 2 percent increase in manpower strength, the ROAD organization exhibited a profound growth in combat power, which in some

- [307]

- weapons systems was over 200 percent. But the new divisions were going to be costly and the full implementation of ROAD would have to await the arrival of new equipment. Until then fixed-wing aircraft would have to be used in place of helicopters, and infantry battalions would substitute for mechanized infantry battalions until armored personnel carriers were available. Furthermore, because of insufficient personnel, the divisions would be maintained at less than ideal strength.34

-

The ROAD Reorganization - The Army Staff began planning for the ROAD reorganization during the summer of 1962. It set the combination of maneuver elements as follows: for the armored division, six tank and five mechanized infantry battalions; for the mechanized infantry division, three tank and seven mechanized infantry battalions; for the infantry division, two tank and eight infantry battalions; and for the airborne division, one assault gun (tank) and eight airborne infantry battalions. The planners anticipated difficulty in finding the men to fill the units because the authorized strength of the Regular Army was only 960,000. Decker recommended that Secretary of the Army Cyrus Vance seek Department of Defense approval for an increase in Army strength as well as the retention of 3,000 KATUSA personnel in both the 1st Cavalry and 7th Infantry Divisions stationed in Korea. If no increase could be obtained, then Decker recommended that divisions in the United States and Korea have fewer maneuver battalions than outlined in the plan.35

- Reorganization of the remaining divisions took place between January 1963 and May 1964 (Table 24). But, as feared, the Department of Defense decided not to seek an increase in the size of the Army, and the reorganization left the Army's divisions at reduced strength except for the units in Europe. Infantry, mechanized infantry, and armored divisions ranged between 14,000 and 16,000 men each, except for the 1st Cavalry and 7th Infantry Divisions, which were authorized about 12,000 men each plus their KATUSA personnel. In the airborne divisions, nine airborne infantry battalions and a tank battalion replaced the eight airborne infantry battalions and assault gun (tank) battalion, but the airborne tank battalion was allotted only experimental equipment. The 82d and 10 1st Airborne Divisions fielded about 13,500 men each. In Germany the airborne capability was moved from the 24th Infantry Division at Augsburg to the 8th Infantry Division at Bad Kreuznach, with one brigade containing all the airborne assets.36

- As the Regular Army completed the ROAD reorganization, the Army made further revisions in the division organizations. Headquarters and service batteries in all artillery battalions except for the Honest John unit were combined to save personnel. More important, the Davy Crocketts were restricted to infantry battalions, and the weapons were to be issued only in response to specific instructions. The Army had debated the appropriate level at which to control nuclear weapons since their Introduction. Like its predecessors, the Kennedy administration continued to stress political control of such weapons.37

- [308]

- Departing from past practice, the Defense Department decided to reorganize the reserve divisions concurrently with the Regular Army's conversion to ROAD. Immediately the old question arose about the number of divisions needed in the reserves to meet mobilization requirements. Studies after the pentomic reorganization suggested that the Army needed forty-three divisions, including twenty-nine in the reserves. The new numbers gave the Army a surplus of eight reserve divisions, but Army leaders also wanted more separate brigades to add flexibility to the force. Late in 1962 the Defense Department approved reorganizing reserve units under ROAD.38

- Following the Defense Department's guidance, the Army Staff decided to retain one Army Reserve division in each of the six Army areas and to eliminate four divisions. Army commanders selected the 63d, 77th, 8 1st, 83d, 90th, and 102d Infantry Divisions for retention and reorganized them under ROAD by the end of April 1963. Each division had two tank and six infantry battalions. With the elimination of the 79th, 94th, 96th, and 103d Infantry Divisions, the An-fly decided to retain their headquarters as a way to preserve spaces for general and field grade officers. It reorganized the units as operational headquarters (subsequently called command headquarters [division]) and directed them to supervise the training of combat and support units located in the former divisional areas and to provide for their administrative support. If an extensive mobilization were to occur, the staff believed that these units could become the nuclei for new divisions.39

- In December 1962 Secretary Vance asked the states and territories to accept a new National Guard troop allotment containing 23 divisions (6 armored and 17 infantry). The Army Staff initially planned to mechanize two of the seventeen infantry divisions, but shortages of equipment forced their retention as standard infantry organizations. Somewhat reluctantly, the governors accepted the new troop basis. By 1 May 1963 the states completed the reorganization, a month ahead of schedule, with the infantry divisions having two tank and six infantry battalions and the armored divisions controlling five tank and four mechanized infantry battalions.40

- Because of equipment shortages each National Guard infantry division lacked its full ROAD base. The states were allowed to omit two company-size units in each division base from the following menu: an airmobile company in the aviation battalion, an air cavalry troop in the reconnaissance squadron, or the Honest John battery in the composite artillery battalion. They chose not to organize a total of 16 air cavalry troops, 13 airmobile companies, and 5 Honest John batteries.41

- In planning the ROAD reorganization, the Army Staff determined that the Regular Army needed one airborne and five infantry brigades for unique missions not appropriate for a division. The airborne brigade was to replace the battle group on Okinawa, thus significantly increasing the forces there, and the infantry brigades were to serve in Berlin, Alaska, the Canal Zone, and the United States. No fixed combination of maneuver elements was established for the brigades, which were, instead, to be tailored for their special missions.42

- [309]

- Maneuver Element Mix of Divisions ROAD Reorganization, 30 June 1965

- [310]

- TABLE 24-Continued

- a Equipment only.

- b Reorganized as an airmobile division 30 June 1965.

- [311]

- 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry, at Fort Richardson, Alaska

- Eventually four more Regular Army brigades were organized in addition to the 193d and 197th Infantry Brigades (Table 25). To test new materiel at Fort Ord, California, the Combat Developments Command formed the 194th Armored Brigade, which assumed the mission of the 5th Infantry Division element. United States Army, Alaska, organized the 171st and 172d Infantry Brigades at Forts Wainwright and Richardson, and U.S. Army, Pacific, organized the 173d Airborne Brigade in March 1963 on Okinawa. The 2d Battle Group, 503d Infantry, stationed there since 1960, and the 1st Battle Group, 503d Infantry, deployed from Fort Bragg, formed the nucleus of that brigade. Shortly thereafter the 173d's battle groups were reorganized as airborne infantry battalions. Berlin, however, did not receive a table of organization infantry brigade but retained the Berlin Brigade organized in 1961 under a mission-oriented table of distribution and allowances.43

- In the Army Reserve some former divisional units assigned to the 79th, 94th, 96th, and 103d Infantry Divisions were used to organize four brigades, which added flexibility to the force as well as provided four general officer reserve billets. In January and February 1963 the 157th, 187th, 191st, and 205th Infantry Brigades were organized with headquarters in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Montana, and Minnesota, respectively (see Table 25). As with the Regular Army brigades, the number and type of maneuver elements in each Army Reserve brigade varied.44

- The 34th, 35th, 43d, and 51st Infantry Divisions, multistate National Guard units, dropped out of the force during the reorganization, and in part were replaced by the 67th (Nebraska and Iowa), 69th (Kansas and Missouri), 86th (Vermont and Connecticut), and 53d (Florida and South Carolina) Infantry Brigades. Each brigade fielded five maneuver elements. In addition, the governors also agreed to maintain the 34th (Iowa), 35th (Missouri), 43d (Connecticut), 51st (South Carolina), and 55th (Florida) Command Headquarters to supervise the training of combat and support units located in the former divisional areas. The states also reorganized the 29th, 92d, and 258th Infantry Brigades, which had been formed in 1959.45

- [312]

Maneuver Element Mix of Brigades ROAD Reorganization, 30 June 1965 - a Company-size unit

- [313]

- The following year, to increase further flexibility in the reserves, the National Guard's 53d and 86th Infantry Brigades were converted to armored brigades, and the 67th Infantry Brigade was reorganized as mechanized infantry. The 53d and 67th retained their five maneuver elements, but the 86th lost one battalion. The 1964 reorganization also provided the 258th Infantry Brigade in Arizona with an armor battalion from Missouri and a field artillery battalion from far-away Virginia.46

-

Airmobility - The ROAD reorganization sought flexible forces to meet worldwide commitments on various battlefields, but by April 1962 McNamara had become concerned about unit mobility. He believed that firepower had been favored over maneuverability and that more aircraft could achieve a better balance. The Army's earlier explorations had focused primarily on the number of aircraft, airplanes and helicopters, needed for observation and transportation, but some championed a tactical role for the latter. McNamara wanted the Army to take a new look at the employment of aircraft in land warfare, particularly the helicopter.47

- In the spring of 1962 the Continental Army Command appointed the Mobility Requirements Board, often referred to as the Howze Board after its president, Lt. Gen. Hamilton H. Howze, to study the matter. After three months of frantic work, including field exercises, the board came to the general conclusion that the adoption of airmobility, the capability of a unit to deploy and receive support from aircraft under the control of a ground commander, was necessary and desirable. In some ways, the transition seemed as inevitable as that from animal to motor transport.48

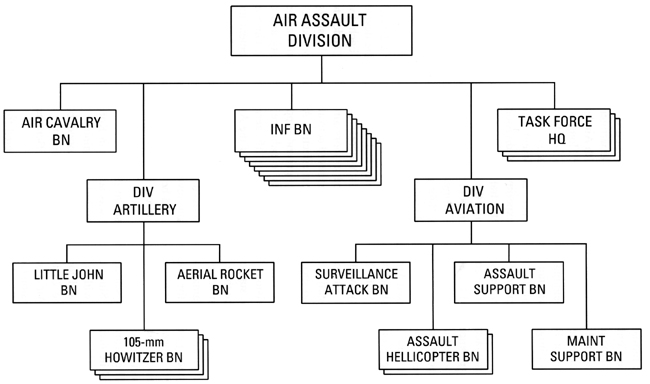

- The Howze Board recommended sweeping changes in the use of aircraft, including the organization of air assault divisions. Although combat support elements were not identified, these divisions were to resemble ROAD organizations (Chart 39) and were to have sufficient aircraft to lift one-third of the divisional combat elements at one time. The division had some fixed-wing aircraft, but most were to be in an air transport brigade, a nondivisional unit, which was to reinforce the transport capabilities of the division. To keep the division as light as possible, the board suggested the use of new, lighter 105-mm. howitzers, Little John rockets, and air-to-ground rockets mounted on helicopters as replacements for the 155mm. howitzers. In addition, infantry was to be relieved of all burdens except for those associated with combat. The board's estimates for divisional aircraft ranged between 400 and 600, but ground vehicle requirements fell from 3,400 to 1,100. Air assault divisions were to replace airborne divisions, and the board recommended assigning airborne-qualified personnel to the new units. Air cavalry combat brigades (ACCB) were endorsed for classic cavalry missions-screening, reconnoitering, and delaying actions. Such brigades were to be strictly air units, and they were to employ attack helicopters in antitank roles. The board also rec-

- [314]

- Howze Board - Air Assault Division, 1963

- [315]

- ommended more aircraft for infantry, mechanized infantry, and armored divisions, and the formation of aviation units for corps, army, and special warfare units.49

- The Continental Army Command developed tables of organization for a ROAD-type air assault division, which the Department of the Army decided to test. The first step was the activation of the 11th Air Assault Division (the former 11th Airborne Division) on 1 February 1963, along with the 10th Air Transport Brigade, at Fort Benning, Georgia. As proposed by the Howze Board, the air transport brigade was not organic to the division, but was to serve as a lines of communications unit for hauling men, equipment, and supplies in the field. In October and November 1964 the experimental division, including 3,250 soldiers from the 2d Infantry Division, and the transport brigade conducted full-scale tests of assault tactics. At the conclusion of the test the director, Lt. Gen. Charles W G. Rich, recommended the addition of both units to the permanent force structure. He reported that the integration of Army aircraft into the ground units provided the crucial maneuver capability for light mobile forces to close with and destroy the enemy. Operating with other divisions, airmobile units offered a balance of mobility and increased Army combat readiness on a theater level.50

- The recommendation to organize an airmobile division set off a debate within the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The U.S. Air Force had been watching the development and growth of Army aviation for years with increasing concern. Each divisional reorganization after World War II resulted in more aircraft being added to these units. The chief of staff, U.S. Air Force, believed activation of the division premature and judged it too specialized to be cost effective. Although not stated, the Air Force felt that airmobility infringed on its ground support mission. Earlier in the 1960s the Air Force had conducted tests to enhance the mobility and combat effectiveness of divisions by improving troop lift, aerial resupply, close air support, and aerial fire support, but found most of the Army's equipment too large for its aircraft. At the time the Air Force had recommended that the Army develop equipment in the infantry division that ,vas more compatible with existing Air Force planes. McNamara now disagreed. He and the Defense Department staff had been pushing for greater Army involvement in aviation since 1962. The Army's proposal met his approval, and he directed the formation of an airmobile division as part of the permanent force. The air transport brigade, however, did not win a place in the force.51

- The Army Staff selected the 1st Cavalry Division to become the Army's first airmobile division. Since that unit was serving in Korea, this resulted in a massive paper shuffle, with men and materiel remaining in place and unit designations moving back and forth. In the end the Korean-based 1st Cavalry Division was replaced by the 2d Infantry Division while the assets of the 2d Infantry Division and 11th Air Assault Division at Fort Benning were used to reorganize the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile).52

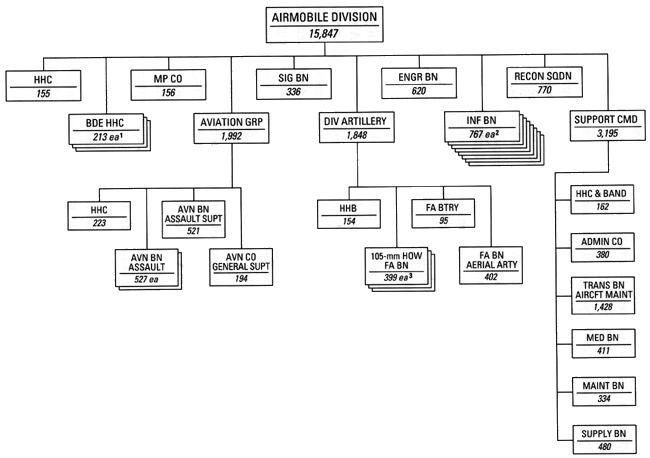

- The 1st Cavalry Division's configuration differed from the test unit (Chart 40). It had no Little John rocket battalion or attack helicopter battalion because the Air

- [316]

- Airmobile Division, 10 July 1965

- 1 One airborne brigade.

- 2 Three airborne battalions.

- 3 One airborne battalion.

- [317]

- Force or other organic divisional weapons assumed the nuclear fire support mission of the rockets. The division fielded an aviation group (a general aviation support company and one assault support and two assault aviation battalions). Divisional helicopters numbered 335. Although the Howze Board believed the number of ground vehicles could be cut by two-thirds, the division was authorized 1,500, or approximately half the number in the other types of ROAD divisions. The vehicles moved supplies, artillery, and antitank weapons and helped in ground reconnaissance. The airmobile infantry battalion had one combat support company (reconnaissance, mortar, and antitank resources) and three rifle companies. Although the battalion lacked ENTACs, 4.2-inch mortars, and .50-caliber machine guns, the infantrymen had a number of new weapons. The M14 rifle was superseded by the lighter MX 16E I (M 16), which put out more firepower and was supplemented by the M79 40-mm. grenade launcher with a dedicated grenadier.53

- The question as to whether the airmobile division should replace the airborne division had not been resolved. Planners decided that one brigade-three infantry battalions and one artillery battalion-was to be authorized airborne-qualified personnel as an interim measure.54

- In summary, the ROAD reorganization ensured the Army's ability to offer flexible responses to changing world conditions. On 1 July 1965, the Army's division and brigade forces consisted of 45 divisions (16 in the Regular Army, 23 in the National Guard, and 6 in the Army Reserve) and 17 brigades (6 in the Regular Army, 7 in the National Guard, and 4 in the Army Reserve). Of the Regular Army divisions, eight served outside the continental United States and eight within. Divisions and brigades in the three components had more flexibility than ever before. As in the past, personnel problems prevented the Army from fielding divisions at their ideal strength, but ROAD's inherent capability for interchanging battalions meant that, if necessary, some units could be brought to wartime standards quickly. The divisions, however, still awaited their true test-combat.

- From the Army's point of view the Kennedy era had produced measurable organizational gains. The budget-driven pentomic divisions had been adopted primarily for political purposes and had never been popular within the Army. While Army leaders were enamored of the new airmobile concept backed by McNamara and others, the ROAD divisions were more popular, providing the Army with solid standard divisional bases and the ability to tailor brigade-size task forces within the division using a variable mix of combat battalions. And with Kennedy's support for expanding the ground components and technological capabilities, the future of the Army seemed more secure in the budget-driven defense community

- [318]

| DivisionRegular Army | Locationof Headquarters | Date | Maneuver Battalions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inf | Mech | Abn | Ar | Amb | Total | |||

| 1st Armored | Ft. Hood, Tex. | Feb 62 | 5 | 4 | 9 | |||

| 1st Cavalry | Ft. Benning, Ga. | Jul 63 | 5 | 2 | 2 | (8b) | 9 | |

| 1st Infantry | Ft. Riley, Kans. | Jan 64 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | ||

| 2d Armored | Ft. Hood, Tex. | Jul 63 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |||

| 2d Infantry | Ft. Benning, Ga. | Apr 64 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | ||

| 3d Armored | Germany | Oct 63 | 5 | 6 | 11 | |||

| 3d Infantry | Germany | Aug 63 | 7 | 3 | 10 | |||

| 4th Armored | Germany | Aug 63 | 5 | 6 | 11 | |||

| 4th Infantry | Ft. Lewis, Wash. | Oct 63 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | ||

| 5th Infantry | Ft. Carson, Colo. | Feb 62 | 8 | 2 | 10 | |||

| 7th Infantry | Korea | Jul 63 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | ||

| 8th Infantry | Germany | Apr 63 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 10 | ||

| 24th Infantry | Germany | Feb 63 | 7 | 3 | 10 | |||

| 25th Infantry | Hawaii | Aug 63 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||

| 82d Airborne | Ft. Bragg, N.C. | May 64 | 9 | la | 10 | |||

| 101st Airborne | Ft. Campbell, Ky. | Feb 64 | 9 | la | 10 | |||

| National Guard | ||||||||

| 26th Infantry | Boston, Mass. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 27th Armored | Syracuse, N.Y. | Apr 63 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |||

| 28th Infantry | Harrisburg, Pa. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 29th Infantry | Baltimore, Md. and Staunton, Va. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 30th Infantry | Raleigh, N.C. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 31st Infantry | Birmingham, Ala. and Jackson, Miss. | Apr/May 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| DivisionNational Guard (cont.) | Locationof Headquarters | Date | Maneuver Battalions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inf | Mech | Abn | Ar | Amb | Total | |||

| 32d Infantry | Milwaukee, Wisc. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 33d Infantry | Urbana, Ill. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 36th Infantry | Austin, Tex. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 37th Infantry | Columbus, Ohio | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 38th Infantry | Indianapolis, Ind. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 39th Infantry | New Orleans, and Little Rock, Ark. | La. May 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 40th Armored | Los Angeles, | Calif Mar 63 | 4 | 6 | 9 | |||

| 41st Infantry | Portland, Ore. and Seattle, Wash. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 42d Infantry | New York, N.Y. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 45th Infantry | Oklahoma City, | Okla. Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 46th Infantry | Lansing, Mich. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 47th Infantry | St. Paul, Minn. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 48th Armored | Macon, Ga. | Apr 63 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |||

| 49th Armored | Dallas, Tex. | Mar 63 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |||

| 49th Infantry | Alameda, Calif. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 50th Armored | East Orange, | N.J. Jan 63 | 4 | 5 | 9 | |||

| Army Reserve | ||||||||

| 63d Infantry | Bell, Calif. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 77th Infantry | New York, | N.Y. Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 81st Infantry | Atlanta, Ga. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 83d Infantry | Cleveland, | Ohio Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 90th Infantry | Austin, Tex. | Mar 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| 102d Infantry | St. Louis, Mo. | Apr 63 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Component | Brigade | Locationof Headquarters | DateReorganized | Maneuver Battalions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inf | Mech | Abn | Ar | Total | ||||

| NG | 29th Infantry | Honolulu, Hawaii | Apr 63 | 3 | 3 | |||

| NG | 53d Armored | Tampa, Fla. | Feb 63 | 2 | 3 | 5 | ||

| NG | 67th Infantry | Lincoln, Neb. | Apr 63 | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| NG | 69th Infantry | Topeka, Kans. | Apr 63 | 2 | 2 | |||

| NG | 86th Armored | Montpelier, Vt. | Apr 63 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| NG | 92d Infantry | San Juan, Puerto Rico | May 64 | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| AR | 157th Infantry | Upper Darby, Pa. | Jan 63 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| RA | 171st Infantry | Ft. Wainwright, Alaska | Jul 63 | 1 | 1 | 1a | 3 | |

| RA | 172d Infantry | Ft. Richardson, Alaska | Jul 63 | 1 | 1 | 1a | 3 | |

| RA | 173d Airborne | Okinawa | Mar 63 | 2 | 1a | 2 | ||

| AR | 187th Infantry | Boston, Mass | Jan 63 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| AR | 191st Infantry | Helena, Mont. | Feb 63 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| RA | 193d Infantry | Ft. Kobbe, Canal Zone | Aug 62 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| RA | 194th Armored | Ft. Ord, Calif. | Dec 62 | 1 | 2 | |||

| RA | 197th Infantry | Ft. Benning, Ga. | Sep 62 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| AR | 205th Infantry | Ft. Snelling, Minn. | Feb 63 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| NG | 258th Infantry | Phoenix, Ariz. | Mar 63 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the Table of Contents