-

-

- In May 1965 President Johnson committed

Regular Army combat units to South Vietnam to halt North Vietnamese incursions

and suppress National Liberation Front insurgents. The 173d Airborne Brigade

from Okinawa was the Army's first combined arms unit to arrive in Southeast

Asia. In July the 2d Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, and the 1st Brigade,

101st Airborne Division, also deployed from the United States. The brigade

from the 101st was originally planned to replace the 173d Airborne Brigade

but, with the need for additional combat units, both brigades remained in

Vietnam. Two months later the 1st Cavalry Division, recently reorganized

as an airmobile unit, reported in country, and the remainder of the 1st

Infantry Division arrived in October.2

-

- As the Army responded to its new

mission, divisions were reorganized using ROAD's tailoring concepts. Before

the 1st Infantry Division deployed, it had field-

- [323]

- Elements of the 173d Airborne Brigade arrive in Vietnam, May 1965.

-

- ed five infantry, two mechanized

infantry, and two armor battalions. With the change in assignment from NATO

reinforcement to counterinsurgency in Vietnam, the division was restructured.

Honest Johns and Davy Crocketts disappeared while requirements for infantry

rose. As no pool of unassigned maneuver battalions existed, two infantry

battalions from the 2d Brigade, 5th Infantry Division, at Fort Devens, Massachusetts,

were relieved and assigned to "The Big Red One." The 1st Division

also reorganized two of its mechanized infantry battalions as standard infantry,

bringing the number of infantry battalions in the division to nine.3

-

- The commander of the 1st Infantry

Division, Maj. Gen. Jonathan O. Seaman, wanted to take a tank battalion

to Vietnam, but General Harold K. Johnson, Chief of Staff since July 1964,

overruled him. Tanks were too vulnerable to mines, and no major enemy armor

threat existed. Furthermore, Johnson thought that the tempo of the battlefield

might be slowed by the limitations of the tank, whose presence might foster

a conventional war mentality rather than the light, fast-moving, unconventional

approach needed. General William C. Westmoreland, commander of U.S. Army,

Vietnam, agreed, reporting that few places existed in Vietnam where tanks

could be employed. Johnson, however, granted Seaman permission to take the

reconnaissance squadron's M48A3 tanks to test the effectiveness of armor

units.4

- [324]

- The decision to commit divisions

and separate brigades to Vietnam triggered a debate within the administration

about the means of expanding the Army to maintain the strategic force. Proposals

ranged from calling up the reserves to increasing the draft. On 28 July,

however, President Johnson rejected use of the reserves and announced that

the Army would base its expansion on volunteers and draftees. Shortly thereafter,

Secretary of Defense McNamara disclosed that one infantry division and three

infantry brigades would be added to the Regular Army in fiscal year 1966

(between 1 July 1965 and 30 June 1966).5

-

- Expansion of the Army began in September

1965, when the First U.S. Army organized the 196th Infantry Brigade. The

2d Brigade, 5th Infantry Division, less its personnel, moved to Fort Carson,

Colorado, where it was refilled, and the remaining men at Fort Devens became

the cadre for the 196th Infantry Brigade. The 196th eventually consisted

of three infantry battalions and the brigade base, a reconnaissance troop,

an engineer company, a support battalion, and a field artillery battalion.

Recruits were assigned to the brigade under a "train and retain"

program, which lessened the impact of limited mobilization on the training

base.6

-

- The brigade's infantry battalions

used a new light structure designed for counterinsurgency warfare. Each

battalion consisted of a headquarters and headquarters company, three rifle

companies, and a combat support company. The latter organization, similar

to that in the airmobile infantry battalion, had mortar, reconnaissance,

and antitank platoons. These light battalions fielded about half the number

of vehicles assigned to a standard infantry battalion, and the riflemen

carried M14 rifles.7

-

- The Fifth U.S. Army activated the

9th Infantry Division, the second unit in the expansion program, at Fort

Riley, Kansas, on 1 February 1966, also employing the "train and retain"

concept. Filled in three increments, the division included one mechanized

infantry battalion and eight infantry battalions. By the end of July the

division had graduated the last cycle of basic trainees, and it was expected

to be combat ready by the end of the year.8

-

- While organizing the 9th Infantry

Division, the Army decided to use it as a part of the Mobile Afloat (Riverine)

Force in Vietnam. Brig. Gen. William E. DePuy, who was serving on Westmoreland's

staff, had developed the idea of a joint Army-Navy force for use in Vietnam's

Mekong River Delta. Army units were to include a brigade-size element that

would live and move on ships and work with two brigade-size shore contingents.

Learning of the riverine mission, Maj. Gen. George S. Eckhardt, the 9th

Division's commander, requested permission to mechanize one infantry battalion,

which would allow him to have one brigade (three infantry battalions) aboard

naval ships and two brigades (one mechanized infantry and two infantry battalions

each) operating from land bases. The Army Staff in Washington agreed, and

Eckhardt organized the second mechanized infantry battalion in October.

To take advantage of the dry season in Vietnam, the division began departing

Fort Riley at the end of 1966 and by February 1967 elements of the "Old

Reliables" took part in the first U.S. Army-Navy riverine operation

of the war.9

- [325]

- 9th Infantry Division's first

base camp in Vietnam, 1966

-

- Shortly thereafter, the Army's buildup

plan went awry. Army Chief of Staff General Johnson had requested his staff

to consider forming a divisional-type brigade (i.e., without the supporting

units common to a separate brigade) to replace the 25th Infantry Division

at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, which was programmed for deployment to Vietnam

in early 1966. Resources scheduled for one of the remaining brigade authorizations

could then be used for the Hawaiian unit. Another proposal, calling for

organizing both the remaining brigades in McNamara's expansion program in

Hawaii, was presented to the Army Staff. However, the Army had activated

the 199th Infantry Brigade at Fort Benning, Georgia, on 1 June 1966 in response

to a request from Westmoreland for a brigade to protect the Long Binh-Saigon

area. Units in Europe were tasked to furnish the cadre for the brigade,

which fielded three light infantry battalions. In less than six months it

deployed to Vietnam.10

-

- Having authority to organize only

one more brigade, the Army activated the 11th Infantry Brigade, a pre-World

War II element of the 6th Infantry Division, in Hawaii on 1 July 1966. Behind

the selection of the 11th was the assumption that the 6th would be the next

division to be activated. The 11th consisted of three infantry battalions,

a support battalion, a reconnaissance troop, and a military police company.

Because of a shortage of personnel and equipment, the brigade lacked its

field artillery battalion, engineer company, and signal platoon authorized

for an independent brigade. But despite their absence, training began and

the missing units were eventually organized. Rather than remaining in Hawaii

as planned, the 11th Infantry Brigade deployed to South Vietnam in December

1967 in answer to an ever-growing need for forces there.11

-

- As the Army's involvement in Southeast

Asia deepened, more units moved to Vietnam. As noted, the 25th Infantry

Division was alerted for deployment in December 1965, and at that time General

Johnson, Army chief of staff, directed that two new infantry battalions

be added to it. However, almost immediately after their organization began,

the battalions were inactivated and replaced with two existing battalions

from Alaska, a means of speeding the departure of the division. When the

division deployed in the spring of 1966 it fielded one mecha-

- [326]

- Men of the 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, fire from old Viet

Cong trenches.

-

- nized infantry battalion and eight

infantry battalions. In addition, the commander, Maj. Gen. Frederick C. Weyand,

insisted on taking the divisional tank battalion.12

-

- The 4th Infantry Division, the last

Regular Army infantry division available in the United States in 1965 for

service in Vietnam, experienced similar turbulence. The Sixth U.S. Army

relieved one tank battalion from the division, equipped the other with M48

tanks, reorganized one mechanized infantry battalion as standard infantry,

and added two more infantry battalions, giving the division the same maneuver

mix (1-1-8) as the 25th Infantry Division. Shortly after the 4th completed

its reorganization in November 1965, the division received 6,000 recruits

to bring all units up to full strength. From June through August 1966 the

4th also assisted forty-seven nondivisional units in preparing for duty

in Vietnam and helped activate the training center at Fort Lewis, Washington.

Nevertheless, the "Ivy Division" deployed to Vietnam between August

and October 1966.13

-

- As the conflict in Vietnam intensified,

Westmoreland requested additional infantry for the 173d Airborne Brigade

and the 1st Cavalry Division. When the 173d Airborne Brigade arrived in

Vietnam, it had only two airborne battalions and was augmented with an Australian

battalion, while the 1st Cavalry Division had only eight airmobile infantry

battalions, which left one of its brigades short a

- [327]

- Elements of 69th Infantry Brigade, part of the Selected Reserve Force,

train at Fort Riley, Kansas, 1966.

-

- maneuver element. After considerable

deliberation, the Continental Army Command activated one airborne battalion

and one airmobile battalion, using personnel drawn from the 101st Airborne

Division and the 5th Infantry Division. Both battalions deployed to Vietnam

in the summer of 1966 to join the 173d Airborne Brigade and the 1st Cavalry

Division, respectively. 14

-

- With the departure of units for

Vietnam, the reserves took on a more significant role. The nation needed

a reserve contingent that could report to mobilization stations on a seven-day

notice. The Army, therefore, created the Selected Reserve Force in the Army

National Guard that included three infantry divisions and six infantry brigades,

one of which was mechanized. To assure the force's equitable geographical

distribution so that one section of the nation would not be asked to bear

the burden of a partial mobilization, each division consisted of the division

base and one brigade in one state, while the other two brigades were divisional

units from adjacent states (Table 26). The Army selected the 28th,

38th, and 47th Infantry Divisions for the force. For the separate brigades,

the states organized three new units, and again their geographic distribution

played a role. Elements from the 36th, 41st, and 49th Infantry Divisions

were withdrawn to form the 36th, 41st, and 49th Infantry Brigades. The divisions

themselves remained active, but each lacked a brigade. The force's other

three brigades were the 29th, 67th, and 69th Infantry Brigades, which had

been organized earlier.15

-

- To improve the readiness of the

Selected Reserve Force, the Army authorized its units to be fully manned,

increased their number of drill days, and raised their priority for receiving

new equipment. Because of shortages in personnel and equipment, McNamara

achieved a long-standing controversial goal of the Defense Department, a

reduction of the reserve troop basis. Those reserve units that were

- [328]

- Divisions and Brigades

- Selected Reserve Force, 1965

-

| Unit |

State |

| 28th Infantry

Division |

Pennsylvania |

|

3d Brigade, 28th Infantry Division |

Pennsylvania |

|

3d Brigade, 29th Infantry Division |

Maryland |

|

3d Brigade, 37th Infantry Division |

Ohio |

| 38th Infantry

Division |

Indiana |

|

76th Brigade, 38th Infantry Division |

Indiana |

|

2d Brigade, 46th Infantry Division |

Michigan |

|

3d Brigade, 33d Infantry Division |

Illinois |

| 47th Infantry

Division |

Minnesota |

|

2d Brigade, 47th Infantry Division |

Minnesota |

|

1st Brigade, 32d Infantry Division |

Wisconsin |

|

3d Brigade, 45th Infantry Division |

Oklahoma |

| 29th Infantry

Brigade |

Hawaii and

California |

| 36th Infantry

Brigade |

Texas |

| 41st Infantry

Brigade |

Washington

and Oregon |

| 49th Infantry

Brigade |

California |

| 67th Infantry

Brigade (Mechanized) |

Iowa and

Nebraska |

| 69th Infantry

Brigade |

Kansas and

Missouri |

-

- judged unnecessary and others that

were undermanned and underequipped could now be deleted with minimum controversy

and their assets used to field contingency forces. Among the units inactivated

were the last six combat divisions in the Army Reservethe 63d, 77th, 81st,

83d, 90th, and 102d Infantry Divisions-and the 79th, 94th, and 96th Command

Headquarters (Division). The 103d Command Headquarters (Division) was converted

to a support brigade headquarters.16

-

- In the spring of 1965 the Army also

responded to a crisis in the Caribbean area. To help restore political stability

and protect United States citizens and property, President Johnson sent

the 82d Airborne Division and other forces to the Dominican Republic. Subsequently,

the Inter-American Peace Force was organized there, and by the autumn the

only United States combat force left was one brigade of three battalions

from the 82d Division. The Joint Chiefs of Staff asked that the brigade

be returned to the United States so that the 82d could resume its place

in the strategic force as a full-strength unit. In response, the Army selected

the 196th Infantry Brigade to replace the divisional brigade in June 1966.

But by the time the 196th had completed its training, stability had returned

to the Dominican Republic, and the president withdrew all United States

forces from the country. 17

-

- To meet Westmoreland's continuing

demand for more troops in Vietnam, President Johnson then approved the transfer

of the 196th Infantry Brigade to Southeast Asia. As the unit had been trained

for street fighting and riot control,

- [329]

- the 196th had to undergo additional

training for combat in Southeast Asia. Also, support units normally attached

to separate brigades in Vietnam had to be organized, including signal and

military police platoons and chemical, military intelligence, Army Security

Agency, military history, and public information detachments. The training

process began in June, and by August 1966 the 196th had deployed to Vietnam.

18

-

-

- After July 1966 no further increase

took place in the number of divisions and brigades until the spring of 1967.

In March of that year, responding to Westmoreland's request for additional

forces, the Army Staff considered organizing either an infantry or a mechanized

infantry brigade for service along the demilitarized zone between North

Vietnam and South Vietnam. The original request called for a mechanized

infantry brigade with personnel drawn mostly from the 1st and 2d Armored

Divisions at Fort Hood. Before the unit could be activated, Westmoreland

decided that he needed a standard separate infantry brigade. On 10 May the

198th Infantry Brigade was activated using personnel from the 1st and 2d

Armored Divisions. Two days later, at the insistence of General Ralph E.

Haines, Vice Chief of Staff and former commander of the 1st Armored Division,

the brigade's three infantry battalions and artillery battalion were inactivated

and replaced with units taken from regiments assigned to the 1st and 2d

Armored Divisions. In turn, new battalions from those regiments were activated

to replace the units taken from the two divisions.19

-

- Westmoreland's plan to use the 198th

along the demilitarized zone between the two Vietnams went astray. Unable

to wait for the brigade to arrive, he established a blocking force in April

1967 with units already in the theater. Designated "Task Force Oregon,"20

it included the 196th Infantry Brigade; the 3d Brigade, 25th Infantry Division;

and the1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division.21

-

- In August 1967 a complex organizational

exchange took place in Vietnam due in large part to the awkward location

of units in relation to their parent divisions. Both the 4th and the 25th

Infantry Divisions had "orphan" brigades that operated outside

their parent division's areas. To correct the problem, Headquarters and

Headquarters Company, 3d Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, and the brigade's

non-color-bearing elements were transferred (less personnel and equipment)

from Tay Ninh to Task Force Oregon at Chu Lai; Headquarters and Headquarters

Company, 3d Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, and its non-color-bearing units

(less personnel and equipment) concurrently joined the 25th Infantry Division

at Tay Ninh. The color-bearing units (infantry and artillery battalions)

attached to the brigades were relieved from the divisions in place and reassigned.

These administrative actions gave the commander of the 25th Infantry Division

operational control of his 3d Brigade for the first time in Vietnam. The

3d Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, however, remained under the operational

control of Task Force Oregon.22

- [330]

- 3d Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, engages the Viet Cong between

Ban Me Thuot and Pleiku.

-

- Soon after forming Task Force Oregon,

Westmoreland decided to replace it with a division. For the unit's designation,

he selected the Americal Division because it was to be organized under circumstances

similar to those in which that division first had been formed during World

War II with National Guard units from Task Force 6814 in New Caledonia.

Westmoreland had originally planned to assign the 11th and 198th Infantry

Brigades, then preparing to deploy, and the 196th Infantry Brigade, already

in Vietnam, to the division. The Army Staff agreed but insisted that the

unit's official designation be the 23d Infantry Division rather than "Americal"

(the Americal Division had been redesignated as the 23d Infantry Division

in 1954). On 25 September 1967 the division was activated to control the

196th Infantry Brigade; the 1st Brigade, 10 1st Airborne Division; and the

3d Brigade, 4th Infantry Division. The division base was to be activated

as requirements were identified.23

-

- In December 1967 the 23d Infantry

Division received its planned brigades. In addition to the 196th Infantry

Brigade, the 11th and 198th Infantry Brigades, reorganized as light infantry

units, had arrived in Vietnam and replaced the brigades of the 4th Infantry

and 101st Airborne Divisions, which returned to their parent units.24

-

- To strengthen the forces in Vietnam,

Westmoreland had requested the remainder of the 101st Airborne Division

by February 1968. Because of ominous intelligence reports about the enemy's

activities, Westmoreland pressured Washington to advance the division's

arrival date. Thus, by 13 December 1967, following the longest troop movement

by air in history, the "Screaming Eagles" arrived in Vietnam.

The division fielded ten airborne infantry battalions, the three that had

deployed with the 1st Brigade in 1965 and the seven that arrived in 1967.25

- [331]

- To replace the 101st Airborne Division

and the 11th Infantry Brigade in the Army strategic contingency forces,

the Army activated the 6th Infantry Division, with nine infantry battalions,

on 24 November 1967. Initially all units of the division were to be organized

at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, but U.S. Army, Pacific, requested that one brigade

be transferred to Hawaii to take over the property and nondeployable personnel

of the 11th Infantry Brigade. Accordingly, the 6th Infantry Division was

split between Fort Campbell (the division base and two brigades) and Schofield

Barracks (one brigade), Hawaii.26

-

- With the attachment of the 11th

Infantry Brigade, originally a component of the 6th Infantry Division, to

the 23d Infantry Division in Vietnam, a new designation was needed for the

6th Infantry Division's third brigade headquarters. The staff, in an unprecedented

move, decided to use the designation 4th Brigade, 6th Infantry Division,

until the 11th could be returned to the division.

-

- January 1968 turned into a month

of crises for the nation. On 23 January, after a series of incidents in

Korea, the North Koreans seized the intelligence ship Pueblo in the

Sea of Japan and incarcerated the crew. This resulted in the strengthening

of United States air and naval forces there and the authorization of hazardous

duty pay for elements of the 2d Infantry Division in Korea. Shortly thereafter

the North Vietnamese began their expected offensive during the Tet holiday

in Vietnam, shocking both Westmoreland and the nation with its intensity.

President Johnson ordered additional forces to Vietnam, including the 3d

Brigade (three airborne infantry battalions) of the 82d Airborne Division

and a Marine Corps unit. Those units arrived in February, and eventually

the 82d's 3d Brigade, organized as a separate brigade, became a part of

the standing forces in Vietnam.27

-

- Because of other contingency plans

the Marine unit had to return to the United States, and Westmoreland asked

for a mechanized infantry brigade to replace it. Army Chief of Staff Johnson

approved the 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division, as the replacement. The

unit, reorganized as a separate brigade fielding one battalion each of infantry,

mechanized infantry, and armor, arrived in Vietnam in July 1968 and was

the last large Army unit to be sent to Southeast Asia (Table 27).28

-

- The seizure of the Pueblo, the

Tet offensive, and the need to maintain the strategic force prompted the

president to call a limited number of National Guard and Army Reserve units

to active duty in the spring of 1968. The call included two brigades from

the National Guard, the 29th Infantry Brigade (Hawaii), which reported to

Schofield Barracks on 13 May, and the 69th Infantry Brigade (Mechanized)

(Kansas), which took up station at Fort Carson. To ease the burden of mobilization,

the brigades acquired elements not previously associated with them. The

29th got the 100th Battalion, 442d Infantry, from the Army Reserve, and

the 69th included the 2d Battalion, 133d Infantry, from the Iowa National

Guard.29

-

- Following the Tet offensive and

the limited reserve mobilization, the Department of Defense ended the buildup

of divisional and brigade units in the

- [332]

- Deployment of Divisions

and Brigades to Vietnam

-

| Unit |

Date Arrived in Vietnam |

| 1st Cavalry Division |

September

1965 |

| 1st Infantry Division |

October

1965 |

|

2d Brigade* |

July 1965 |

| 4th Infantry Division |

October

1965 |

|

2d Brigade* |

August 1966 |

| 1st Brigade, 5th

Infantry |

Division

June 1968 |

| 9th Infantry Division |

December

1966 |

|

2d Brigade* |

January

1967 |

| 23d Infantry Division |

September

1967 |

|

11th Infantry Brigade* |

December

1967 |

|

196th Infantry Brigade* |

August 1966 |

|

198th Infantry Brigade* |

October

1967 |

| 25th Infantry

Division |

April 1966 |

|

2d Brigade* |

January

1966 |

|

3d Brigade* |

December

1965 |

| 3d Brigade, 82d

Airborne Division |

February

1968 |

| 10 1st Airborne

Division |

December

1967 |

|

1st Brigade* |

July 1965 |

| 173d Airborne

Brigade |

May 1965 |

| 199th Infantry

Brigade |

December

1966 |

-

- * Arrived separately.

-

- active Army. At peak strength the

Army had 19 divisions (counting the 3 brigades attached to the 23d as 1

division), with 7 divisions serving in Vietnam, 2 in Korea, 5 in Europe,

and 5 in the United States, and 11 brigades, of which 4 were in Vietnam,

2 in Alaska, I in the Canal Zone, and 4 in the continental United States.

-

-

- Airmobility gave commanders the

ability to concentrate men and their firepower on the Vietnamese battlefield

quickly, and the Army planned to organize a second airmobile division as

early as 1966. These plans foundered until 1968 because of the aviation

needs of other combat units in Vietnam and the general shortage of aviation

equipment. But after the 101st Airborne Division arrived in Southeast Asia,

U.S. Army, Vietnam, began a phased reorganization of the division into an

airmobile configuration, which took over a year to complete.30

-

- During the conversion of the 101st,

the Army adopted a decentralized approach to aircraft maintenance. Initially

the 101st, like the 1st Cavalry Division, was to have a large aircraft maintenance

battalion, but the need of company-, battery-, and troop-size aviation units

for their own maintenance organiza-

- [333]

- tions resulted in a cellular maintenance

structure. In the 1st Cavalry Division and 101st Airborne Division an aircraft

maintenance detachment was activated to support each company-size aviation

unit.31

-

- When the 101st was reorganized as

an airmobile unit, confusion and contention reigned over its designation.

Instructions from Washington renamed the division the 101st Infantry Division

(Airmobile) because the designation was thought to accurately describe its

mission. Officers in Vietnam opposed the change, and after much discussion

the Army Staff sent new instructions redesignating both the 101st Airborne

Division and the 1st Cavalry Division as "air cavalry." In July

1968 Westmoreland replaced Harold K. Johnson as Army Chief of Staff, and

Westmoreland directed that the divisions retain their historic designations.32

-

- Ever conscious of ways to save personnel,

U.S. Army, Vietnam, requested permission in September 1968 to reorganize

the 23d Infantry Division (the Americal) along the lines of other infantry

divisions to save over 500 personnel spaces. The request proposed that the

11th, 196th, and 198th Infantry Brigades be redesignated as the 1st, 2d,

and 3d Brigades, 23d Infantry Division, and that a complete division base

be organized. Westmoreland, as chief of staff, approved the reorganization

of the division but not the numerical redesignation of the brigades. He

directed that the brigades be attached rather than assigned as organic elements

of the division. His reasons for retaining the separate brigade designations

included the complexity of the units' histories and the desire not to change

the designations of units serving in Vietnam. On 15 February 1969, the 23d

was thus reorganized with a division base resembling that in other infantry

divisions, except for the attached brigade headquarters and the omission

of the organic cavalry squadron. The 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry, an element

of the 1st Armored Division, had been serving with the "Americal"

because General Haines, the former 1st Armored Division commander, had wanted

the squadron to represent "Old Ironsides" in Vietnam. The staff

chose not to tamper with this arrangement.33

-

- To increase firepower, some divisions

and brigades received an additional battalion or battalions of infantry

without upsetting their structure. As noted above, the 1st Cavalry Division

and the 173d Airborne Brigade each had an additional infantry battalion

assigned in 1966. The following year the 173d was assigned a fourth infantry

battalion, and after the 1968 Tet offensive the 9th Infantry Division and

the 11th, 198th, and 199th Infantry Brigades each gained an additional infantry

battalion. At the peak of the buildup the combined arms teams in Vietnam

fielded eighty-three infantry and armor battalions.34

-

- Divisions and brigades deployed

to Vietnam with infantry, light infantry, airborne infantry, and airmobile

infantry battalions but, responding to the demands of the conflict, U.S.

Army, Vietnam, reorganized most of them under modified light infantry tables

of organization. Each of these battalions consisted of a headquarters and

headquarters company, four rifle companies, and a combat support

- [334]

- company. The fourth rifle company

provided a unit for base defense and allowed the battalion to operate with

three companies outside the base camp.35

-

- Combat brought about several changes

in the infantryman's weapons. The light M16 rifle became the standard individual

weapon, and a one-man light antitank weapon (LAW) often replaced the heavy

and awkward 90-mm. recoilless rifle. Because of the nature of the fighting,

heavier infantry weapons, such as the ENTAC, 4.2-inch mortar, and 106-mm.

recoilless rifle, saw little service. When used, both the 81-mm. and 4.2-inch

mortars were usually "slaved" to fire direction centers at American

fire bases. Units did not suffer a loss of effective firepower because their

mobility allowed them to concentrate their remaining weapons, while improved

field radio communications aided in putting tremendous amounts of supporting

fire at their disposal. Given organic, attached, and supporting aviation

and signal units, all divisions and brigades had extensive airmobile and

communications capabilities.36

-

- Although only one armor company,

equipped with 90-mm. self-propelled antitank guns, assigned to a brigade

and three divisional armor battalions, equipped with M48A3 tanks, served

in Vietnam, divisions and brigades there had considerable armor. Each divisional

reconnaissance squadron, except for the two in the airmobile divisions,

had tanks and reconnaissance vehicles. The latter carried additional machine

guns and gun shields, permitting the reconnaissance squadrons to function

as armor. Also, the eight mechanized infantry battalions in Vietnam frequently

performed as light armor units, using modified armored personnel carriers.

By 1969 some reconnaissance and mechanized infantry units employed Sheridans,

the M551 armored reconnaissance assault vehicles, in place of the light

tank and armored personnel carriers. The Sheridan filled the need for a

light tracked vehicle with greater firepower than the M113 armored personnel

carrier.37

-

- Artillery, the third combat arm

assigned to divisions and brigades, also underwent modifications in Vietnam.

In the two airmobile divisions, a 155-mm. howitzer battalion was permanently

attached after the 1st Cavalry Division demonstrated that the heavy howitzer

could be moved by helicopter. Because of the large operational areas of

divisions and separate brigades, their direct support artillery battalions

often had four firing batteries, which were created in various ways. In

the 173d Airborne Brigade, a fourth battery was authorized; in the 23d Infantry

Division, each direct support battalion consisted of two five-gun and two

four-gun batteries; and in the 1st Infantry Division, one or two 4.2-inch

mortar platoons were attached to direct support artillery battalions as

Batteries D and E.38

-

- By mid-1969 the seven divisions

and four separate brigades in Vietnam reached their final configuration

(Table 28). The ROAD building-block concept worked well, particularly

in a war that was fought by brigades with divisions serving in a corps-like

role. The Army, however, had difficulty meeting the demands of commanders

for more tactical maneuver units because there was no pool of separate battalions

to draw upon when needed for additional support.

- [335]

- Maneuver Elements Assigned

to Divisions and Brigades in Vietnam

- 30 June 1969

-

-

| Division/Brigade |

Battalions |

| Inf |

Mech Inf |

Mod lnf |

Armor |

Total |

| 1st Cavalry Division |

|

|

9 |

|

9 |

| 1st Infantry Division |

|

2 |

7 |

|

9 |

| 4th Infantry Division |

|

1 |

8 |

1 |

10 |

| 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry

Division |

|

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

| 9th Infantry Division |

2 |

1 |

7 |

|

10 |

| 23d Infantry Division |

|

|

11 |

|

11 |

| 25th Infantry Division |

|

3 |

6 |

1 |

10 |

| 1st Brigade, 82d Airborne

Division |

|

|

3 |

|

3 |

| 101st Airborne Division |

|

|

10 |

|

10 |

| 173d Airborne Brigade |

|

|

4 |

* |

4 |

| 199th Infantry Brigade |

|

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

Total

|

2 |

8 |

70 |

3 |

83 |

-

- * A company.

-

-

- The Army directed its major effort

in the mid- and late- 1960s toward Vietnam, and divisions and brigades in

other commands supported that endeavor. All active duty divisions and brigades

in the United States furnished units or men for service in Vietnam, and

as a result most fell below combat-ready status. Ultimately the maneuver

element mix in the 1st and 2d Armored Divisions was reduced to four tank

and four mechanized infantry battalions, which was considerably below the

prototype of six tank and five infantry battalions. To maintain them as

fully manned armored divisions, the Army designated one mechanized infantry

and two armor battalions from the National Guard as "round-out"

units for each. Round-out units maintained a close association with their

designated divisions, even taking annual field training with them, but were

not on active federal service.39

-

- Although the Army did not withdraw

any divisions from Europe for service in Vietnam, US. Army, Europe, also

contributed to the combat effort. As already noted, the cadre for the 199th

Infantry Brigade had come from Europe. Beginning in February 1966 the Army

levied the command in Europe for officers and enlisted personnel with specific

skills, particularly junior grade and noncommissioned officers. Within a

year 1,800 soldiers a month were departing for duty in Vietnam to meet the

levy. This drain on the European forces severely affected unit leadership

and the readiness of the remaining forces.40

- [336]

- In the armored and mechanized infantry

divisions designed to fight in Europe, aviation battalions were eliminated

after a study on the use of aircraft rationalized that heavy divisions did

not need extensive air lines of communications. Fifty-seven helicopters

remained in each division, spread throughout the reconnaissance squadron,

maintenance battalion, division artillery, and division and brigade headquarters

companies. The operation of the divisional airfield passed to a new transportation

detachment attached to the supply and transport battalion. Although not

stated, the forty aircraft removed from each armored and mechanized infantry

division were needed in Vietnam.41

-

- Notwithstanding personnel and equipment

problems in Europe, divisions still had to be prepared to counter Soviet

mechanized forces, primarily through increased firepower. In the 3d, 8th,

and 24th Infantry Divisions an armor battalion replaced a mechanized infantry

battalion in 1966. (Armor battalions required fewer people than mechanized

infantry battalions but had more firepower.) The change gave the divisions

a maneuver mix of four armor and six mechanized infantry battalions. In

those battalions, as well as in the reconnaissance squadron and the artillery

battalions, an air defense section that used the new shoulder-fired, low-altitude,

Redeye guided missile was introduced. In the artillery of both the armored

and mechanized infantry divisions, self-propelled 155-mm. howitzers replaced

105-mm. pieces because the larger howitzers could fire both conventional

and nuclear warheads and had a longer range. The capability of firing nuclear

rounds from conventional artillery tubes also eliminated the need for the

jeep-mounted Davy Crocketts.42

-

- Although the military and political

leadership still perceived a Soviet threat in Western Europe, the first

reduction in the number of Army divisions stationed in Europe since the

beginning of NATO took place during the Vietnam conflict. The desire of

the United Kingdom, the Federal Republic of Germany, and the United States

to realign their balance of payments precipitated the reduction. By mutual

agreement one division (less one brigade) and some smaller units in Germany

were to return to the United States but were to remain under the operational

control of the commander in Europe and return periodically to Germany for

training exercises. The divisional brigade that remained in Germany was

to be replaced by one from the United States during each training exercise.

The staff named the plan REFORGER, "Return of Forces to Germany."

During the first half of 1968 the 24th Infantry Division, without its 3d

Brigade, moved to Fort Riley.43

-

- The following December the Department

of Defense announced that the first REFORCER exercise would take place in

early 1969 but, to prevent personnel turbulence, no rotation of brigades

would occur. Since the Warsaw Pact countries had invaded Czechoslovakia

the previous August, the timing of the exercise, between 5 January and 23

March 1969, demonstrated to NATO that the United States would honor its

commitments.44

- Special mission brigades throughout

the world also contributed to the forces in Vietnam. In late 1965 an infantry

battalion of the 197th Infantry Brigade,

- [337]

- which supported the Infantry School,

was inactivated at Fort Benning to provide personnel for expanding the Army

in Vietnam. In a personnel-saving action, the Combat Developments Command's

194th Armored Brigade at Fort Ord was replaced by a battalion-size combat

team and reorganized at Fort Knox to support the Armor School in place of

the 16th Armor Group. Under the new configuration the brigade included one

mechanized infantry and two armored battalions. The 171st and 172d Infantry

Brigades in Alaska each lost their aviation company, and in the 193d Infantry

Brigade in the Canal Zone, the airborne battalion was replaced with a standard

infantry battalion. (Table 29 shows the composition of divisions

and brigades outside Vietnam in 1969.)45

-

- In 1968 Secretary of Defense Clark

Clifford decided to reduce forces in the continental United States to four

divisions because the budget did not permit filling and maintaining five

divisions. He directed the inactivation of the 6th Infantry Division, the

activation of a brigade to replace the 82d's 3d Brigade in Vietnam, and

higher manning levels for the 69th Infantry Brigade attached to the 5th

Infantry Division at Fort Carson and the 29th Infantry Brigade at Schofield

Barracks. The 6th Division was inactivated on 25 July 1968, and the rest

of Clifford's proposals were accomplished by early 1969.46

-

- Four weeks after the 6th Infantry

Division was inactivated, the Vice Chief of Staff, General Bruce Palmer,

Jr., considered reactivating the division in response to the invasion of

Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies. Lacking men to organize the unit,

the staff considered the division's reactivation a "show the flag"

action. The plan was eventually dropped because it was an empty gesture.

Thus, the strategic reserve forces in the United States stood at four divisions

in September 1968 and remained at that level until the close of the Vietnam

era.47

-

- During the 1960s the Department

of Defense continued to scrutinize the reserve forces and to question the

number of divisions and brigades as well as the redundancy of maintaining

two reserve components, the National Guard and the Army Reserve. In 1967

Secretary of Defense McNamara decided that 15 combat divisions in the Army

National Guard were unnecessary and cut the number to 8 divisions (1 mechanized

infantry, 2 armored, and 5 infantry), but increased the number of brigades

from 7 to 18 (1 airborne, 1 armored, 2 mechanized infantry, and 14 infantry).

The loss of the divisions did not set well with the states. Their objections

included the inadequate maneuver element mix for those that remained and

the end to the practice of rotating divisional commands among the states

that supported them. Under the proposal, the remaining division commanders

were to reside in the state of the division base. No reduction, however,

in total Army National Guard strength was to take place, which convinced

the governors to accept the plan.48

-

- The states reorganized their forces

accordingly between 1 December 1967 and 1 May 1968. All remaining divisions

were shared by two or more states (Table 30). Divisional brigades

located in states without the division base consist-

- [338]

- Maneuver Element Mix

of Divisions and Brigades on Active Duty

- Outside Vietnam, 30 June 1969

-

- Battalions

| Unit |

Location |

Inf |

Mech Inf |

Abn lnf |

Armor |

Total |

| 1st Armored Division |

Fort Hood, Tex. |

|

4 |

|

4 |

8 |

| 2d Armored Division |

Fort Hood, Tex. |

|

4 |

|

4 |

8 |

| 2d Infantry Division |

Korea |

5 |

2 |

|

2 |

9 |

| 3d Armored Division |

Germany |

|

5 |

|

6 |

11 |

| 3d Infantry Division |

Germany |

|

6 |

|

4 |

10 |

| 4th Armored Division |

Germany |

|

5 |

|

6 |

11 |

| 5th Infantry Division |

Fort Carson, l Colo. |

|

8 |

|

2 |

10 |

| 7th Infantry Division |

Korea |

5 |

2 |

|

2 |

9 |

| 8th Infantry Division |

Germany |

|

6 |

|

4 |

10 |

| 24th Infantry Division |

Fort Riley,2 Kans. |

|

6 |

|

3 |

9 |

| 82d Airborne Division |

Fort Bragg,3 N.C. |

|

|

9 |

|

9 |

| 29th Infantry Brigade |

Hawaii |

3 |

|

|

|

3 |

| 171st Infantry Brigade |

Alaska |

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

| 172d Infantry Brigade |

Alaska |

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

| 193d Infantry Brigade |

Canal Zone |

3 |

|

|

|

3 |

| 194th Armored Brigade |

Fort Knox, Ky. |

1 |

|

|

2 |

3 |

| |

TOTAL |

17 |

52 |

9 |

39 |

117 |

-

- 1 Does not include the 1st Brigade

in Vietnam, but does include the 69th Infantry Brigade.

- 2 One brigade in Germany.

- 3 Does not include the 1st Brigade

in Vietnam, but does include the 4th Brigade, 82d Airborne Division.

-

- [339]

- National Guard Divisions

and Brigades, 1968

-

| Unit |

Location |

| 26th Infantry

Division |

Massachusetts and Connecticut |

| 28th Infantry

Division |

Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia |

| 30th Armored Division |

Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee |

| 30th Infantry

Division (M)* |

North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia |

| 38th Infantry

Division |

Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio |

| 42d Infantry Division |

New York and Pennsylvania |

| 47th Infantry

Division |

Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota |

| 50th Armored Division |

New Jersey, New York, and Vermont |

| 29th Infantry

Brigade |

Hawaii and California |

| 32d Infantry Brigade |

Wisconsin |

| 33d Infantry Brigade |

Illinois |

| 36th Infantry

Brigade |

Texas |

| 39th Infantry

Brigade |

Arkansas |

| 40th Armored Brigade |

California |

| 40th Infantry

Brigade |

California |

| 41st Infantry

Brigade |

Oregon |

| 45th Infantry

Brigade |

Oklahoma |

| 49th Infantry

Brigade |

California |

| 53d Infantry Brigade |

Florida |

| 67th Infantry

Brigade (M)* |

Nebraska |

| 69th Infantry

Brigade |

Kansas |

| 71st Airborne

Brigade |

Texas |

| 72d Infantry Brigade

(M)* |

Texas |

| 81st Infantry

Brigade |

Washington |

| 92d Infantry Brigade |

Puerto Rico |

| 256th Infantry

Brigade |

Louisiana |

-

- *Mechanized.

-

- ed of the maneuver elements, an

artillery battalion, an engineer company, a medical company, a forward support

maintenance company, and an administrative section. The remainder of each

division was located in the state with the division base. Infantry divisions

had ten maneuver battalions, as did the mechanized infantry divisions, except

the 47th, which had eleven. The 30th and 50th Armored Divisions had ten

and eleven maneuver battalions, respectively. A single state maintained

each of the eighteen separate brigades, except for the 29th (Hawaii), which

had elements in the continental United States.49

-

- The Army Reserve brigades also felt

McNamara's axe. Initially the Defense Department planned no combat forces

for the Army Reserve, but congressional

- [340]

- opposition saved the 157th (Pennsylvania),

187th (Massachusetts), and 205th (Minnesota and Iowa) Infantry Brigades.

All their expensive armor and mechanized infantry battalions, however, were

eliminated, leaving each brigade with only three standard infantry battalions.

In the western part of the country, the poorly manned 191st Infantry Brigade

fell out of the force, with its headquarters being inactivated in February

1968 at Helena, Montana. The following June an armor battalion was restored

to the 157th Infantry Brigade to increase its capabilities.50

-

- Concurrent with reorganizing the

reserves, Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor authorized a new Selected

Reserve Force in 1967 to lessen the heavy burden of the accelerated training

program. All units in the original force retained their equipment but lost

their priority for new equipment. The new "selected reserve" force,

designed specifically to reinforce the Army in Southeast Asia, consisted

of the 26th and 42d Infantry Divisions and the 39th, 40th, 157th, and 256th

Infantry Brigades. But two years later the secretary abolished the force,

seeking to bring all National Guard and Army Reserve units to the same readiness

level.51

-

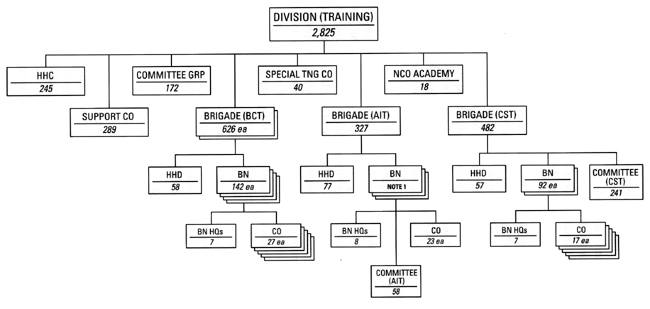

- The Defense Department did not question

the number of training divisions in the Army Reserve, but they were reorganized

to conform to Regular Army training centers. In 1966 the Continental Army

Command developed new tables of organization that eliminated regiments in

training divisions and replaced them with brigades (Chart 41). The

division fielded two basic combat training brigades, each consisting of

four battalions with five training companies each; an advanced individual

training brigade, three battalions with three to six companies or batteries

of field artillery, armor, infantry, and engineers each; and a combat support

training brigade, two battalions of five companies each, and a committee

directorate. All basic training instructors were concentrated in a committee

group. Along with the division headquarters and headquarters company, the

division had support and special training companies and a noncommissioned

officer/drill sergeant academy. These changes enhanced the training division's

ability for self-sustainment in both reserve and active duty status, but

it could not train as many men under the new structure. All thirteen divisions

were organized under the new tables by 1968.52

-

-

- On 8 June 1969, President Richard

Nixon announced that 25,000 men would be withdrawn from Vietnam as part

of a "Vietnamization" effort, which involved transferring increased

responsibility for conducting all aspects of the war to the Republic of

Vietnam. An underlying cause was the disillusionment of the American people

with a war that seemed permanently stalemated. Popular sentiment favored

the return of U.S. forces from Vietnam and a retrenchment of U.S. involvement

in world affairs, particularly in Asia.53

- [341]

- Training Division, 1966

-

- 1 Each battalion will contain 3-6 of any of the following types of companies/batteries

(AIT): Infantry, Field Artillery, Armor, or Engineer.

-

- [342]

- Elements of the 9th Infantry Division begin departing Vietnam, July

1969.

-

- General Creighton Abrams, commander

of U.S. Army, Vietnam, designated two brigades of the 9th Infantry Division

serving in the Mekong Delta to be the first combined arms units to leave.

In July 1969 the 2d Brigade, 9th Infantry Division, departed Vietnam and was

inactivated at Fort Riley. The following month the division base and the 1st

Brigade moved to Hawaii to become a part of the Pacific reserve. The 3d Brigade,

9th Infantry Division, was reorganized as a separate brigade and continued

to serve in Vietnam.54

-

- The incremental redeployments from

Vietnam between 1969 and 1972 caused considerable confusion, but less than

in previous conflicts where demobilization had to be accomplished rapidly.

Shortly after the withdrawal began, Acting Secretary of the Army Thaddeus

R. Beal announced a reduction in total Army forces for economic reasons.

One result was the immediate inactivation of the 9th Infantry Division,

except for its brigade in Vietnam. To replace the 29th Infantry Brigade

in Hawaii, which was to be released from federal service along with

other reserve units in December 1969, the US. Army, Pacific, activated the

4th Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, on 6 December and returned the 29th

Infantry Brigade to state control on 13 December. When disclosing the formation

of the new brigade, Secretary of Defense Clifford stressed that the 25th

Infantry Division was not returning from Vietnam, explaining that the designation

was selected only as a tribute to the division's service in Vietnam. Nevertheless,

the announcement caused some rumors that the 25th would soon be home.55

- [343]

- Meanwhile, in September 1969 President

Nixon announced another troop withdrawal. The only large unit in that increment

was the 3d Brigade, 82d Airborne Division, which returned to Fort Bragg

in December to replace the division's 4th Brigade. As noted, the Army released

the reserve units in December, including the 69th Infantry Brigade. To maintain

a full division at Fort Carson, the Fifth U.S. Army activated the 4th Brigade,

5th Infantry Division, a Regular Army unit.56

-

- A pattern of redeployment soon emerged.57

As one group of units left Vietnam the president announced another reduction.

Under redeployment policies, selected units ceased to receive replacements

sixty days before leaving the command; their equipment was turned in for

storage or redistribution; and personnel were generally reassigned elsewhere

in Vietnam. Usually each returning unit had only a small detachment to safeguard

its colors or flags and essential records. Few soldiers had opportunity

to participate in any welcome-home ceremonies. Unneeded company size or

smaller units were inactivated in Vietnam, while battalion-size and larger

units, including divisions and brigades, returned to the United States for

retention or inactivation. The Army generally followed these policies over

the next two and one-half years as divisions and brigades left Vietnam (Table

31).58

-

- To accommodate some redeploying

units, the Army rearranged the location of divisional designations in the

Regular Army. In 1970 the 1st Infantry Division replaced the 24th Infantry

Division at Fort Riley and in Germany, and the 4th Infantry Division succeeded

the 5th Infantry Division at Fort Carson. The 1st Brigade, 25th Infantry

Division, replaced the 4th Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, in Hawaii. The

1st and 4th Infantry Divisions simultaneously became mechanized infantry

units, adapting to a NATO reinforcement role. In the 1st, the maneuver elements

consisted of 4 armor and 6 mechanized infantry battalions, while the 4th

included 1 infantry, 2 armor, and 7 mechanized infantry battalions.59

-

- Another complex exchange of divisions

took place in 1971 when the 1st Cavalry Division returned to the United

States. At that time the Army planned to test a new air cavalry combat brigade

in conjunction with airmobile and armor units. The staff had programmed

the 1st Armored Division at Fort Hood as the test unit, but when the 1st

Cavalry Division returned from Southeast Asia it replaced the armored division,

which was to be inactivated. Protests by former members of "Old Ironsides"

against taking the unit designation out of the active force led Westmoreland,

now Army chief of staff, to retain the division on the active rolls by transferring

it to Germany where it replaced the 4th Armored Division. The 1st Cavalry

Division, less its 3d Brigade, which remained in Vietnam, was reorganized

at Fort Hood.60

-

- The 173d Airborne Brigade posed

a problem for redeployment planners because it had been the first large

unit sent to Vietnam. They wanted to retain it in the force, but the brigade

was no longer needed in Okinawa as negotiations were under way to return

the island to Japan. Westmoreland decided to station the brigade at Fort

Campbell until the 101st Airborne Division returned and to use the unit

or some of its elements later to reorganize the 101st. The 173d

- [344]

- Redeployment of Divisions

and Brigades From Vietnam

-

-

| Unit |

Date Redeployed |

|

| Remarks |

| 1st Cavalry Division

(less 3d Brigade) |

April 1971 |

Replaced the

1st Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas |

| 3d Brigade |

June 1972 |

Replaced the 4th

Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division |

| 1st Infantry Division |

April 1970 |

Replaced the

24th Infantry Division at Fort Riley, Kansas, and in Germany |

| 4th Infantry Division

(less 3d Brigade) |

December

1970 |

Replaced the 5th

Infantry Division at Fort Carson, Colorado |

| 3d Brigade |

April 1970 |

Replaced the 4th

Brigade, 5th Infantry Division, at Fort Carson, Colorado |

| 1 st Brigade,

5th Infantry Division |

August 1971 |

Inactivated |

| 9th Infantry Division

(less 3d Brigade) |

July 1969 |

Inactivated |

| 3d Brigade |

October

1970 |

Inactivated |

| 23d Infantry Division |

November

1971 |

Inactivated |

| 11th Infantry

Brigade |

November

1971 |

Inactivated |

| 198th Infantry

Brigade |

November

1971 |

Inactivated |

| 25th Infantry

Division (less 2d Brigade) |

December

1970 |

1st Brigade replaced

the 4th Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii;

concurrently division headquarters and 3d Brigade reduced to zero

strength |

| 2d Brigade |

April 1971 |

Reduced to zero

strength |

| 3d Brigade, 82d

Airborne Division |

December

1969 |

Replaced the 4th

Brigade, 82d Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina |

| 101st Airborne

Division (less 1st, 2d, and 3d Brigades) |

March 1972 |

Returned to Fort

Campbell, Kentucky |

| 1st Brigade |

January

1972 |

Returned to Fort

Campbell, Kentucky |

| 2d Brigade |

February

1972 |

Returned to Fort

Campbell, Kentucky |

| 3d Brigade |

December

1971 |

Returned to Fort

Campbell, Kentucky |

| 173d Airborne

Brigade |

August 1971 |

Inactivated at

Fort Campbell, 1972 |

| 196th Infantry

Brigade |

June 1972 |

Inactivated |

-

- [345]

- arrived at its new post in September

1971, and the following January the brigade headquarters was inactivated while

some of the brigade's elements were reassigned to the 101st.61

-

- In June 1972 the last two U.S. combat

brigades, the 3d Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, and the 196th Infantry Brigade,

left Vietnam. The cavalry brigade rejoined its parent unit at Fort Hood,

replacing the 4th Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, while the 196th was inactivated

at Oakland, California. The last brigade element, the 3d Battalion, 21st

Infantry, departed Vietnam in August 1972, marking the end of U.S. Army

divisions' and separate brigades' direct participation in the war in Vietnam.62

-

- Shortly after the withdrawal of

troops from Vietnam had begun in 1969, President Nixon adopted a new doctrine

for military involvement in world affairs. He based the "Nixon Doctrine"

on several principles: the United States would honor all treaty commitments;

it would provide a shield if a nuclear power threatened one of its allies

or a nation whose survival was considered vital to U.S. national interest;

and it would offer military and economic assistance to its allies when requested.

But the United States expected a nation directly threatened to assume primary

responsibility for its own defense. Following these principles, Nixon directed

a 20,000-man reduction of Army forces in Korea by 30 June 1971. To accomplish

that goal, the 7th Infantry Division concluded its 21-year stay in Korea

and returned to Fort Lewis, where it was inactivated on 2 April. Its departure

left only the 2d Infantry Division, now reorganized to consist of two armor

and six infantry battalions, augmented by Korean forces.63

-

- With a smaller Army the nation could

no longer maintain two brigades in Alaska, and Westmoreland decided to eliminate

one. In September 1969 both brigades had been reorganized from mechanized

to light infantry as modernization and cost-saving measures. U.S. Army,

Alaska, chose to inactivate the 171st Infantry Brigade and reorganize the

172d. Under the new alignment a light infantry battalion and the reconnaissance

troop were stationed at Fort Wainwright, while two light infantry battalions

and the remainder of the brigade base were at Fort Richardson. The reduction

of forces in Alaska was completed by November 1972.64

-

- By May 1972 post-Vietnam retrenchment

had cut the active forces by about 650,000 men from its peak wartime figure

of 1.5 million. The number of Regular Army divisions fell to twelve, and

only four special-mission brigades remained. The divisions, particularly

those in the United States, were far from being effective fighting teams.

The vicissitudes of the war in Vietnam and the reductions in the size of

the Army combined to erode combat effectiveness. The decline in unit capabilities

had been less abrupt than in 1919 or 1945-46 but just as alarming.

-

- The years between 1965 and 1972

had been tumultuous for both the Army and the nation. Organizationally,

however, the ROAD concept had proved sound. The active Army increased more

than 66 percent during this period, and divisions

- [346]

- and brigades had been tailored for

various missions within various regional commands. Light units campaigned

effectively in Vietnam, heavy units continued to meet NATO commitments in

Europe, and Army forces in the United States covered contingencies for all

commands. The major problem for the Army was the acquisition of personnel

and equipment. All divisions and brigades, except for those in Vietnam,

suffered a decline in readiness, the price of meeting the demands of the

conflict. Soldiers were withdrawn from Vietnam as individuals, and most

units returned to the United States as paper organizations. The Army appeared

to have solved its organizational problems associated with flexible response,

but it had not come to grips with its perennial difficulty, shortages of

human and materiel resources.

- [347]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-