-

-

- The Nixon doctrine and smaller budgets drove Secretary of Defense Melvin

R. Laird to set an Army goal of 21 divisions, 13 in the Regular Army and

8 in the National Guard, by 1973. Structured and equipped primarily to defend

Western Europe, the divisions were designed for conventional warfare against

the Soviet Union's heavy armor forces. To complement the divisions, the

Army maintained 21 separate combined arms brigades, 18 in the Army National

Guard and 3 in the Army Reserve. In addition, the Regular Army continued

to employ special mission brigades as theater defense forces.2

-

- In October 1969 the Army Staff suspended all new work on revised tables

of organization and equipment for armored, infantry, and mechanized infantry

divisions because the proposed changes required too many men to field them.

Instead, it directed the Combat Developments Command to develop divisions

of fewer than

- [353]

- TOW (tutee-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided) missile

-

- 17,000 men. The project, entitled AIM (armored, infantry, and mechanized

infantry divisions), would occupy Army planners' attention for the next

several years and focus primarily on the European battlefield.3

-

- In their final form the new AIM tables neither altered the overall ROAD

doctrine nor radically modified divisional structures but addressed ways

to counter various types of Soviet threats. To defend against low-altitude

hostile aircraft and surface targets, the tables provided each division

with an air defense artillery battalion equipped with Chaparral missiles

and Vulcan guns, weapons that had been under development since 1964. The

new battalion gave divisions the first dedicated antiaircraft artillery

unit since pentomic reorganization. Aviation companies reappeared in mechanized

infantry and armored divisions to enhance air support. In the divisional

support command, adjutant general and finance companies replaced the administration

company to improve personnel services, and automatic data processing equipment

was added to provide centralized control of personnel and logistics. Eventually

automatic data processing led to the introduction of a materiel (supply

and maintenance) management center in each division.4

-

- In infantry, mechanized infantry, and armor battalions, the tables concentrated

combat support (scouts, mortars, air defense and antitank weapons, ground

surveillance equipment, and maintenance resources) into a combat support

company. Tube-launched, Optically tracked, Wire-guided missiles (TOWS) replaced

ENTACs and 106-mm. recoilless rifles as antitank weapons in the infantry

and mechanized infantry battalions. Since the TOW was only just emerging

from its developmental stage, the tables approved the retention of the 106-mm.

recoilless rifle as a temporary measures.5

-

- Modernization of armored, infantry, and mechanized infantry divisions

became an ongoing process primarily to due to shortages of equipment. Because

of the need for antiaircraft weapons in the divisional area, the Air Defense

Artillery School at Fort Bliss, Texas, inaugurated a program in the spring

of 1969 to activate and train Chaparral-Vulcan battalions, which were assigned

to divisions upon completion of training. After the new divisional tables

were published in

- [354]

- 1970, the Honest John rocket battalions were eliminated as divisional units,

and new Lance missile units replaced them at corps level. The adjutant general

and finance companies were introduced in 1971, the aviation companies returned

in 1972, the materiel management center appeared in 1973, and new combat intelligence

companies were assigned beginning in 1974 (replacing the combat intelligence

unit, which had been regularly attached to every division since the pentomic

reorganization of 1957). The company provided a battlefield information coordination

center to plan and manage the collection of intelligence and consolidated

ground surveillance radar and remote sensors under one commander.6

-

- The standard maneuver element mix of the mechanized infantry division

was also adjusted for the European battlefield. An additional armor battalion

was added to the model division, making the mix five armor and six mechanized

infantry battalions. Subsequently the Army activated additional armor battalions

for the 3d and 8th Infantry Divisions stationed in Germany in 1972. That

same year the Continental Army Command replaced a mechanized infantry battalion

with an armor battalion in the 4th Infantry Division at Fort Carson, Colorado,

and in 1973 made a similar change, giving the division a maneuver element

mix of four armor and six infantry battalions. In the armored division the

maneuver mix remained at five mechanized infantry and six armor battalions.

Infantry divisions fielded one armor, one mechanized infantry, and eight

"foot" infantry battalions.7

-

- To have thirteen Regular Army divisions, the Army Staff directed the 25th

Infantry Division, which fielded only one brigade after leaving Vietnam,

to be reorganized at Schofield Barracks in the spring of 1972. Because of

environmental issues surrounding the use of Schofield Barracks at that time,

the division had only two brigades (six infantry battalions), with the Hawaii

Army National Guard agreeing to "round out" the 25th with the

29th Infantry Brigade. Since the brigade included the 100th Battalion, 442d

Infantry, from the Army Reserve, the division was truly representative of

the "Total Army."8

-

- For the thirteenth Regular Army division in the force, the Continental

Army Command reactivated the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis on 21 April

1972. Over the next few months the division organized one armor, one mechanized

infantry, and seven infantry battalions, which was one less infantry unit

than the standard for an infantry division. The division base had all its

authorized elements except for the Honest John battalion, then under consideration

for elimination in all divisions. Two years later the Army Staff directed

the 9th to establish one brigade as an armored unit to support contingency

plans, and when it became evident that the active Army was unable to field

an additional tank battalion, the Washington Army National Guard agreed

to furnish a tank battalion as a round-out unit.9

-

- While organizing the thirteen-division force, the Continental Army Command

determined that the 197th Infantry Brigade, assigned to the Infantry School

at Fort Benning, Georgia, was overmanned for its training support mission

in the post-Vietnam Army. To provide personnel needed for the school, the

command directed that the school support troops be reorganized and the 197th

be

- [355]

- restructured as a unit in the Strategic Army Force. On 21 March 1973 the

brigade officially joined the strategic force, fielding one battalion each

of infantry, mechanized infantry, and armor. 10

-

- The Regular Army also maintained three other brigades with special missions

in the early 1970s. The 172d and 193d Infantry Brigades served in Alaska

and the Canal Zone, respectively, as theater defense units. At Fort Knox,

Kentucky, the 194th Armored Brigade was a brigade in name only. It had been

reduced to a headquarters, and its infantry, armor, and field artillery

units had been assigned directly to the Armor School. The 194th, however,

remained at Fort Knox as a command and control organization for various

units ranging in size from a finance section to a supply and service battalion.11

-

- In late 1972 the Army approved the reorganization of the 101st Airborne

Division using new airmobile divisional tables. Since returning from Vietnam,

the 101st had comprised two airmobile brigades and one airborne brigade,

with the airborne brigade separately deployable. Defense planners had insisted

that the division serve as a quick reaction force until the thirteen-division

force was combat ready. The existing division employed a conglomeration

of old, new, and test tables of organization and equipment, which created

organizational problems in the division's combat and support units, particularly

in signal resources and medium-range field artillery. After extensive study

Army Chief of Staff Creighton Abrams approved the reorganization of the

division under new tables, which continued to provide two airmobile brigades

and one airborne brigade, with its supporting elements parachute qualified.

Signal, engineer, maintenance, and aviation resources were increased; and

an air defense artillery battalion, adjutant general and finance companies,

and a materiel management center added. A 155-mm. howitzer battalion, which

had been used in Vietnam by the division, was made an organic element in

the tables, but in fielding the new structure, Abrams directed that the

155-mm. towed howitzer battalion be temporarily eliminated as a way to reduce

personnel requirements.12

-

- By early 1974 the thirteen-division Regular Army force was deemed combat

ready, and contingency plans no longer required an airborne brigade in the

101st. United States Army Forces Command, which in part replaced the United

States Continental Army Command in 1973, reorganized the division as a completely

airmobile organization. The reorganization also eliminated internal rivalries

between the higher paid paratroopers (soldiers on "jump status")

and the regular airmobile soldiers. To compensate for its loss of airborne

status in recruiting, Maj. Gen. Sidney B. Berry, the commander of the 101st,

decided to capitalize on the division's air assault training, requesting

that the division's parenthetical designation be changed from "airmobile"

to "air assault" and that the personnel who completed air assault

training be authorized to wear a special badge. The Army Staff approved

the change in designation and eventually authorized the air assault badge.13

- [356]

- General Abrams

-

- The airborne division was the last type of division to be modernized.

As in other divisions, the new tables provided an air defense artillery

battalion, adjutant general and finance companies, and a materiel management

center. The structure also continued to include a much debated light armor

battalion, equipped with reconnaissance airborne assault vehicles, which

had been assigned to the division in 1969. The most significant change,

however, was the replacement of the supply company with a supply and service

battalion, which provided the division with over 500 additional service

personnel. The one remaining active airborne division, the 82d, with nine

airborne infantry battalions and an armor battalion, adopted the new structure

by the fall of 1974.14

-

- After returning from Vietnam the 1st Cavalry Division had been given two

primary missions: evaluate the interaction of armor, mechanized infantry,

airmobile infantry, and air cavalry (armed helicopters); and fill the role

of an armored division in the strategic reserve force. To cover the second

mission, the division continued to use National Guard round-out units, which

had originally been designated for the 1st Armored Division-the unit that

the 1st Cavalry Division replaced at Fort Hood in 1971. To evaluate the

interaction of armor, air cavalry, and mechanized and airmobile infantry,

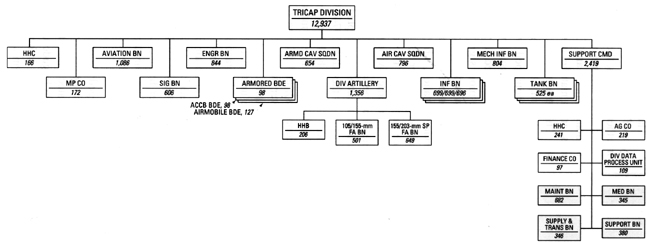

the "First Team" was organized under new tables (Chart 42) that

included resources for an air cavalry combat brigade (ACCB). This was not

to be the type of brigade the Howze Board had suggested in 1962, which was

to be a completely air-fighting unit, but one that troops in Vietnam and

Europe had been testing under limited conditions as a combined arms assault

unit. With the division combining armor, infantry, and air cavalry in one

organization, Westmoreland coined the term "TRICAP" (triple capability)

to describe it.15

-

- During the evaluation of TRICAP two views emerged about the structure

of an air cavalry combat brigade. Some planners saw it primarily as a separate

antiarmor brigade with infantry and air cavalry integrated into attack helicopter

squadrons without organic support. Others desired the brigade to be a strong,

well-balanced, versatile organization with attack helicopter, infantry,

reconnaissance, artillery, and combat support units that could perform a

variety of missions, including an antitank role. During the summer of 1972

Vice Chief of Staff

- [357]

- TRICAP Division

-

-

-

- [358]

- Bruce Palmer noted that a brigade consisting of only attack helicopter squadrons

was an expensive organization. (The table for such a proposed squadron called

for 88 (45 attack, 27 observation, and 16 utility) helicopters. Therefore

he did not envision it as an independent strike force. Nevertheless, he directed

further development of an attack helicopter squadron because of concerns voiced

by General Michael S. Davison, the commander of U.S. Army, Europe, and Seventh

Army. In Europe Soviet armor forces greatly outnumbered their NATO counterparts,

and Davison needed some sort of long-range capability that could destroy,

disrupt, or at least delay enemy mechanized units behind the main battlefield.

Following the development of the squadron, Palmer believed that the planners

could sort out the matter of whether the brigade should be assigned to a division

or a corps. 16

-

- By the end of 1972 the course of the TRICAP/ACCB studies appeared set.

The Combat Developments Command recommended reorganizing the 1st Cavalry

Division to consist of two armored brigades (with two mechanized infantry

and four armor battalions divided between them) and one air cavalry combat

brigade. The latter, to be employed as a part of the division or independently,

was to consist of an airmobile infantry battalion and two attack helicopter

squadrons. The brigade was to have no organic support battalion. Round-out

battalions continued to be assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division so that

it could deploy as a full armored division along with the air cavalry combat

brigade. 17

-

- Before the ink dried on the new instructions, Abrams decided to reorganize

the air cavalry combat brigade as a separate unit for employment at corps

level and to make the division exclusively an armored unit. With one organic

brigade organized as air cavalry, the 1st Cavalry Division with only two

mechanized infantry and four armor battalions lacked the necessary ground-gaining

and holding ability of a normal armored division. On 21 February 1975 the

Army thus organized the 6th Cavalry Brigade (Air Combat) at Fort Hood, Texas.

The first of its type, the brigade consisted of a headquarters and headquarters

troop, an air cavalry squadron (without the armored cavalry troop), two

attack helicopter battalions, a support battalion, and a signal company.

Strictly an air unit, the brigade's mission was to locate, disrupt, and

destroy enemy armored and mechanized units by aerial combat power. In the

summer of that year the 1st Cavalry Division was reorganized wholly as an

armored division with four armor and four mechanized infantry battalions

in the Regular Army. One mechanized infantry and two armor battalions in

the National Guard continued to round out the division.18

-

- Although the 21-division, 21-brigade force did not alter the number of

reserve divisions and brigades, the reserve components underwent numerous

changes after the Army withdrew from Vietnam. Like the Regular Army, the

Guard began increasing its heavy forces in 1971 with the 32d (Wisconsin)

and 81st (Washington) Infantry Brigades being converted to mechanized infantry.

In 1972 the states began modernizing their divisions and brigades using

the recently published tables, but they lacked the materiel to complete

the process.

- [359]

-

- The Chaparral short-range air defense surface-to-air missile system;

below, the Vulcan air defense system.

-

-

- [360]

- To field air defense artillery battalions, Guard units used "Dusters,"

M42 tracked vehicles with dual-mounted 40-mm. antiaircraft guns, rather than

Chaparrals and Vulcans. As only limited numbers of M60 tanks, M551 assault

vehicles (Sheridans), and AH-1 helicopters (Cobras) were available, the Guard

continued to use vintage equipment.19

-

- Shortly after the National Guard reorganized its divisions, a controversy

arose over the command of the 30th Armored Division, a multistate unit supported

by Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama. Tennessee was about to appoint a

new divisional commander, and the governors of Mississippi and Alabama threatened

to withdraw their units from the division unless their officers had the

opportunity to be the divisional commander. Governor Winfield Dunn of Tennessee

objected to rotation of the commander's position, and Secretary of the Army

Robert F. Froehlke supported him. Abrams therefore directed Maj. Gen. Francis

S. Greenlief, Chief of the National Guard Bureau, to review such command

arrangements in all Guard divisions.20

-

- Before Greenlief could propose a solution, other events made the question

moot. The Department of Defense directed the Army to convert six reserve

brigades from infantry to armored or mechanized infantry as reinforcements

for Europe. In the meantime, Mississippi Governor William L. Waller decided

to withdraw his units from the 30th Armored Division. Given the requirement

to convert some brigades, the Army Staff decided to have Tennessee, Mississippi,

and Alabama each organize an armored brigade and to move the allotment of

the armored division to Texas, which could support the necessary units itself.

After much negotiating, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi agreed to organize

the 30th, 31st, and 155th Armored Brigades, and Texas took on the 49th Armored

Division in 1973. For the other three brigades, the Army replaced the 30th

Infantry Division, another tri-state division, with the 30th (North Carolina),

48th (Georgia), and 218th (Louisiana) Infantry Brigades and reorganized

the 40th Infantry Division in California. All were mechanized infantry.

The reorganization did not change the total number of reserve divisions

or brigades, and the National Guard continued to field 8 divisions (1 mechanized

infantry, 2 armored, and 5 standard infantry) and 18 brigades (3 armored,

6 mechanized infantry, and 9 standard infantry), while the Army Reserve

supported 3 brigades (I mechanized infantry and 2 infantry).21

-

- By 30 June 1974, the Army had attained the 21-division, 21-brigade force

(Tables 32 and 33). The 25th Infantry Division at Schofield Barracks,

with two brigades, and the 197th Infantry Brigade at Fort Benning were regarded

as equivalent to one division in the Regular Army. Some Regular Army divisions

in the continental United States, however, had round-out battalions from

the reserves to meet mobilization missions. More serious was the fact that

reserve divisions and brigades continued to experience readiness problems.

Recruitment lagged because of the end of the draft, and equipment shortages

continued due to the lack of money. The "total force" thus exhibited

significant weaknesses.22

- [361]

- The 21-Division Force, June 1974

-

| Division |

Component |

Location of Headquarters |

Maneuver Battalions |

| Inf |

Mech |

Ar |

Abn |

AAST |

| 1st Armored |

RA |

Ansbach, Germany |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

| 1st Cavalry 1&3 |

RA |

Fort Hood, Tex |

|

2 |

4 |

|

|

| 1st Infantry2 |

RA |

Fort Riley, Kans. |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

| 2d Armored3 |

RA |

Fort Hood, Tex. |

|

4 |

4 |

|

|

| 2d Infantry |

RA |

Camp Casey, Korea |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

| 3d Armored |

RA |

Frankfurt, Germany |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

| 3d Infantry |

RA |

Wuerzburg, Germany |

|

6 |

5 |

|

|

| 4th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Carson, Colo. |

|

6 |

4 |

|

|

| 8th Infantry |

RA |

Bad Kreuznach, Germany |

|

6 |

5 |

|

|

| 9th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Lewis, Wash. |

7 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| 25th Infantry3 |

RA |

Schofield Barracks, Hawaii |

6 |

|

|

|

|

| 26th Infantry |

NG |

Boston, Mass. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| 28th Infantry |

NG |

Harrisburg, Pa. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| 38th Infantry |

NG |

Indianapolis, Ind. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| 40th Infantry |

NG |

California |

|

6 |

4 |

|

|

| 42d Infantry |

NG |

New York, N.Y. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| 47th Infantry |

NG |

St. Paul, Mich. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

| 49th Armored |

NG |

Austin, Tex. |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

| 50th Armored |

NG |

East Orange, N.J. |

|

|

5 |

6 |

|

| 82d Airborne |

RA |

Fort Bragg, N.C. |

|

|

1 |

9 |

|

| 101st Airborne |

RA |

Fort Campbell, Ky. |

|

|

|

|

9 |

-

- 1 Does not include the 6th Cavalry Brigade units.

- 2 One brigade deployed forward in Germany.

- 3 Less round-out unit or units assigned.

- [362]

- The 21-Brigade Force, June 1974

-

| Brigade |

Location of Component |

Headquarters |

Maneuver Battalions |

| 1nf |

Mech |

Ar |

Lt Inf |

| 29th Infantry |

NG and AR |

Honolulu, Hawaii |

|

2 |

|

|

| 30th Armored |

NG |

Jackson, Tenn. |

|

1 |

2 |

|

| 30th Infantry (M)1 |

NG |

Clinton, N.C. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 31st Armored |

NG |

Tuscaloosa, Ala. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 32d Infantry (M)1 |

NG |

Milwaukee, Wisc. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 33d Infantry |

NG |

Chicago, Ill. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 39th Infantry |

NG |

Little Rock, Ark. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 41st Infantry |

NG |

Portland, Oreg. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 45th Infantry |

NG |

Edmond, Okla. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 48th Infantry (M)1 |

NG |

Macon, Ga. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 53d Infantry |

NG |

Tampa, Fla. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 67th Infantry (M)1 |

NG |

Lincoln, Neb. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 69th Infantry |

NG |

Topeka, Kans. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 81st Infantry (M)1 |

NG |

Seattle, Wash. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 92d Infantry |

NG |

San Juan, Puerto Rico |

3 |

|

|

|

| 155th Armored |

NG |

Tupelo, Miss. |

|

1 |

2 |

|

| 157th Infantry (M)1 |

AR |

Horsham, Pa. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 172d Infantry2 |

RA |

Fort Richardson, Alaska |

|

|

|

3 |

| 187th Infantry |

AR |

Wollaston, Mass. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 193d Infantry2 |

RA |

Fort Kobbe, Canal Zone |

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 194th Armored |

RA |

Fort Knox, Ky. |

No assigned battalions |

| 197th Infantry3 |

RA |

Fort Benning, Ga. |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

| 205th Infantry |

AR |

Fort Snelling, Minn. |

3 |

|

|

|

| 218th Infantry (M)1 |

NG |

Newberry, S.C. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

| 256th Infantry |

NG |

Lafayette, La. |

3 |

|

|

|

-

- 1 Mechanized unit.

- 2 Special mission brigade.

- 3 The brigade and the 25th Infantry Division with two active brigades counted

as a divisional equivalent.

- [363]

-

- As the Army struggled to meet the 21-division, 21-brigade force, General

Abrams turned his attention to the nation's ability to execute its military

strategy without resorting to nuclear weapons and to the task of providing

the resources needed to deal with a variety of world situations. In testimony

before congressional committees in 1974, he characterized the Regular Army's

portion of the 21-division force as a high-risk, "no room for error"

force.23

He further testified that through more efficient management, cuts

in nonessential support activities, and reorganization of various headquarters

throughout the Army, a 785,000-man Regular Army could support sixteen divisions.

Congress gave no opposition, and the Department of Defense lent its support.

Therefore, Abrams directed his staff to plan for three additional Regular

Army divisions by 1980.24

-

- Although some officers on Abrams' staff were thunderstruck at the directive,

since a 785,000-man force had not been sufficient in the past to maintain

16 Regular Army divisions, the Army Staff eventually developed plans involving

both regulars and reserves to raise a 24-division force. A mechanized infantry

division and two infantry divisions were to be phased into the force over

the next few years. The first increment was to include activating three

new divisional brigades, reorganizing the 1st Cavalry Division as an armored

division (as decided earlier), and adjusting the number of maneuver elements

in other divisions in the United States. Phase two was to provide the base

and an additional brigade for each of the three new divisions. Phase three

was vague, but the divisions were to be completed using reserve round-out

units.25

-

- During the summer of 1974 Forces Command began to implement the 24-division

force. To provide some of the resources, various headquarters throughout

the Army were reorganized, cuts were made in nonessential support activities,

and the 1st and 4th Infantry Divisions each saw one of their Regular Army

maneuver battalions inactivated and replaced by a National Guard round-out

unit. On 21 October the command activated the 7th Infantry Division headquarters

and the 1st Brigades of the 5th, 7th, and 24th Infantry Divisions at Forts

Polk, Ord, and Stewart, respectively. The 7th and 24th were standard, or

"foot," infantry divisions, and the 5th was mechanized infantry.

Because Fort Polk, in Louisiana, lacked adequate housing facilities, the

brigade of the 5th fielded only two maneuver battalions. The larger facilities

at Fort Ord, California, allowed the 7th to support four maneuver battalions,

and the brigade of the 24th at Fort Stewart, Georgia, fielded three. As

noted above, Forces Command organized the 6th Cavalry Brigade (Air Combat)

as a separate corps-level aviation unit and reorganized the 1st Cavalry

Division as an armored division consisting of four armor and four mechanized

infantry battalions in the Regular Army and three round-out battalions from

the National Guard.26

-

- Phase two of the program required organizing the base and a second brigade

for each division. For the 5th and 24th Infantry Divisions elements of the

194th Armored Brigade and the 197th Infantry Brigade were to be used, but

all ele-

- [364]

- Round-out Units, 1978

-

| Division |

Unit |

Component |

| 1st Cavalry |

2d Battalion, 120th Infantry |

N.C. NG |

| |

2d Battalion, 252d Armor |

N.C. NG |

| |

1st Battalion, 263d Armor |

S.C. NG |

| 1st Infantry |

2d Battalion, 136th Infantry |

Minn. NG |

| 2d Armored |

3d Battalion, 149th Infantry |

Ky. NG |

| |

1st Battalion, 123d Armor |

Ky. NG |

| |

2d Battalion, 123d Armor |

Ky. NG |

| 4th Infantry |

1st Battalion, 1 17th Infantry |

Tenn. NG |

| 5th Infantry |

256th Infantry Brigade |

La. NG |

| 7th Infantry |

41st Infantry Brigade |

Wash. NG |

| |

8th Battalion, 40th Armor |

Army Reserve |

| 9th Infantry |

1st Battalion, 803d Armor |

Wash. NG |

| 24th Infantry |

48th Infantry Brigade |

Ga. NG |

| 25th Infantry |

29th Infantry Brigade |

Hawaii NG and Army Reserve |

-

- ments of the second brigade in the 7th Infantry Division were to be newly

organized. On 28 August 1975, however, the Army canceled the plans to use

the 194th Armored and 197th Infantry Brigades because of congressional pressure

to improve the ratio of combat to support troops. All units in phase two

were to be formed new in the Regular Army.27

-

- Forces Command began activating phase two units in the fall of 1975, organizing

all required Regular Army units within two years. While the Regular Army

units were being activated, Louisiana, Washington, and Georgia agreed that

the 256th, 41st, and 48th Infantry Brigades would be assigned to round out

the 5th, 7th, and 24th Infantry Divisions, respectively. Because the 7th

needed an armor battalion, the 8th Battalion, 40th Armor, an Army Reserve

unit, was assigned to it. Hence, in order to raise the 24-division force,

the round-out concept was extended to all divisions except those forward

deployed in Germany and Korea and the airborne and airmobile units (Table

34). 28

-

- Although Forces Command did not use the 194th Armored and 197th Infantry

Brigades to organize the new divisions, both brigades were assigned strategic

missions after 21 October 1975. Responding to General Abrams' congressional

testimony to provide a better balance of combat to support units, the Army

Staff converted 4,000 general support spaces to combat positions in the

continental United States, and the command used some of them to reorganize

the 194th as a strategic reserve unit. The brigade eventually included one

mechanized infantry battalion and two tank battalions. In addition, it continued

to support the Armor School at Fort Knox. 29

- [365]

- In 1974 congressional dissatisfaction led Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia to

sponsor an amendment requiring the Army to reduce the number of support forces

in Europe by 18,000 officers and enlisted personnel but permitting those spaces

to be used to organize combat units there. The new units could include battalions

or smaller units of infantry, armor, field and air defense artillery, cavalry,

engineers, special forces, and aviation, which were to improve the visibility

of the nation's combat power in Europe.30

-

- To execute the Nunn amendment US. Army Forces Command and U.S. Army, Europe,

and Seventh Army agreed to a plan for organizing a mechanized infantry brigade

and an armored brigade for Europe, which were known as Brigade-75 and Brigade-76.

Under the plan the headquarters and a support battalion for each brigade

were to be stationed in Germany while the infantry, armor, and field artillery

battalions, engineer companies, and cavalry troops from the United States

were to rotate every six months. No provisions were made for dependents

to accompany the soldiers since they were to be away from home on temporary

duty for only 179 days. The short duration of the assignment was to be a

cost-saving measure, which indirectly also attacked the balance of payment

problem between the United States and its allies, and a morale booster.

To support the rotation of Brigade-75, the first unit in the program, the

Army selected the 2d Armored Division, at Fort Hood, Texas. Between March

and June 1975 the 3d Brigade, 2d Armored Division, deployed to Germany,

with its headquarters at Grafenwoehr and its elements scattered at various

training areas. A few weeks before each unit departed Fort Hood, Forces

Command activated a similar unit, including Headquarters and Headquarters

Company, 4th Brigade, 2d Armored Division, to maintain the three-brigade

structure of the division in the continental United States. During the deployment

the Army Staff approved a request from Forces Command to use a battalion

from the 1st Cavalry Division, rather than have all elements from the 2d

Armored Division, in order to reduce personnel turbulence in the 2d. Because

of the shortage of tank crews, the Army changed Brigade-75 from an armored

to a mechanized infantry unit. Another factor in the decision to deploy

a mechanized brigade was the shortage of tanks resulting from U.S. replacement

of tanks the Israelis had lost in their 1973 war against the Arabs. In September

1975 the first rotation of brigade elements between Germany and Fort Hood

began.31

-

- Forces Command selected the 4th Infantry Division to support Brigade-76

and in December 1975 activated the 4th Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, at

Fort Carson, Colorado. The following year the brigade moved to Germany.

To lighten the burden of the 4th Infantry Division at Fort Carson, a mechanized

infantry battalion from the 1st Infantry Division at Fort Riley was included

in the rotation scheme. Following the procedure used to send Brigade-75

to Europe, new organizations were activated in the 1st and 4th Infantry

Divisions to maintain their divisional integrity.32

-

- As elements of the 3d Brigade, 2d Armored Division, and the 4th Brigade,

4th Infantry Division, rotated, the Army monitored the effect on the budget,

readiness,

- [366]

- and morale. Evidence soon suggested that the rotation of the brigades improved

neither cost effectiveness nor readiness. Therefore, the Army decided that

the brigades would be assigned permanently to US. Army, Europe, and Seventh

Army. The reassignment of the 4th Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, took place

in the fall of 1976. At that time the 3d Battalion, 28th Infantry, the element

of the 1st Infantry Division supporting the brigade, was reassigned to the

4th Infantry Division. To improve the alignment of Allied forces in Europe,

Army leaders decided to station Brigade-75 (the 3d Brigade, 2d Armored Division)

in northern Germany, where no American combat unit had served since the end

of World War 11. Such problems as the lack of housing, particularly for dependents,

and opposition from German nationals over the impact of the troops on the

environment, caused the elements of the brigade to continue to rotate until

the questions could be resolved. Two years later, after building a new military

complex at Garlstedt, the 3d Brigade, 2d Armored Division, became a permanent

part of the European forces. At Fort Hood the 4th Brigade, 2d Armored Division,

and the battalion of the 1st Cavalry Division that supported the brigade were

inactivated. A new battalion was assigned to the 2d Armored Division from

its traditional regiments to replace the 1st Cavalry Division unit inactivated

in Germany. The net result of the Nunn amendment on divisional forces was

two more brigades forward deployed in Germany but a reduction of one brigade

in the 2d Armored Division in the United States.33

-

- Readiness became the watchword for the seventies. Although some Army leaders

believed that the first battle of any future war might be the last and final

ground battle, a high state of readiness served as a deterrent against aggression.

Improving readiness in the Army's 24-division force thus became the primary

objective of Army Chief of Staff Fred C. Weyand, who was appointed after

Abrams died in office in September 1974. Weyand requested the National Guard

Bureau to explore the consolidation of the 50th Armored and the 26th, 28th,

38th, 42d, and 47th Infantry Divisions into single or bi-state configurations

and to consider the possibility of forming five more brigades. The latter

were to be organized only with the secretary of defense's approval. In 1975

and 1976 the 50th Armored Division was reorganized in New Jersey and Vermont,

the 28th Infantry Division in Pennsylvania, and the 42d Infantry Division

in New York. Former elements of the 28th from Maryland and Virginia supported

the new 58th and 116th Infantry Brigades, respectively. In 1977 Ohio dropped

out of the 38th Infantry Division, leaving Indiana and Michigan to maintain

it. Ohio organized the 73d Infantry Brigade. The only divisional element

not concentrated within each division's new recruiting area was the air

defense artillery battalions. With these changes, the Army reached the 24-division,

24-brigade force (Tables 35 and 36). Also, the 36th Airborne Brigade

and 149th Armored Brigade headquarters were organized and federally recognized

in the National Guard, but they were headquarters only, without assigned

elements.34

-

- The Army Reserve continued to maintain three brigades within the total

force. These brigades were the least combat ready units in the Army. Without

the draft, the

- [367]

- The 24-Division Force, 1978

-

-

| Division |

Component |

Locationof Headquarters |

Maneuver Battalions |

| Inf |

Mech |

Ar |

Abn |

AAst |

Remarks |

| 1st Armored |

RA |

Ansbach, Germany |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

| 1st Cavalry1 |

RA |

Fort Hood, Tex. |

|

4 |

5 |

|

|

See Table 34 |

| 1st Infantry2 |

RA |

Fort Riley, Kans. |

|

5 |

4 |

|

|

See Table 34 |

| 2d Armored3 |

RA |

Fort Hood, Tex. |

|

6 |

5 |

|

|

See Table 34 |

| 2d Infantry |

RA |

Camp Casey, Korea |

4 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

|

| 3d Armored |

RA |

Frankfurt, Germany |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

| 3d Infantry |

RA |

Wuerzburg, Germany |

|

6 |

5 |

|

|

|

| 4th Infantry4 |

RA |

Fort Carson, Colo. |

|

7 |

5 |

|

|

See Table 34 |

| 5th Infantry (-) |

RA |

Fort Polk, La. |

|

3 |

3 |

|

|

See Table 34 |

| 7th Infantry (-) |

RA |

Fort Ord, Calif |

6 |

|

|

|

|

See Table 34 |

| 8th Infantry |

RA |

Bad Kreuznach, Germany |

|

6 |

5 |

|

|

|

| 9th Infantry (-) |

RA |

Fort Lewis, Wash. |

|

7 |

1 |

l |

|

See Table 34 |

| 24th Infantry (-) |

RA |

Fort Stewart, Ga. |

|

4 |

2 |

|

|

|

| 25th Infantry (-) |

RA |

Schofield Barracks, Hawaii |

6 |

|

|

|

|

See Table 34 |

| 26th Infantry |

NG |

Boston, Mass. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 28th Infantry |

NG |

Harrisburg, Pa. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 38th Infantry |

NG |

Indianapolis, Ind. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 40th Infantry |

NG |

Long Beach, Calif. |

|

6 |

5 |

|

|

|

| 42nd Infantry |

NG |

New York, N.Y. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 47th Infantry |

NG |

St. Paul, Mich. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 49th Armored |

NG |

Austin, Tex. |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

| 50th Armored |

NG |

Somerset, N.J. |

|

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

| 82d Airborne |

RA |

Fort Bragg, N.C. |

|

|

1 |

9 |

|

|

| 101st Airborne |

RA |

Fort Campbell, Ky. |

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

-

- 1 One battalion supported the 3d Brigade, 2d Armored Division (Brigade-75).

- 2 The 1st Infantry Division Forward was in Germany.

- 3 Supported 3d Brigade, 2d Armored Division (Brigade-75) in Germany.

- 4 Supported 4th Brigade, 4th Infantry Division (Brigade-76) in Germany.

-

- [368]

- The 24-Brigade Force, 1978

-

| Brigade |

Component |

Locationof Headquarters |

Maneuver Battalions |

| Inf |

Mech |

Ar |

Lt lnf |

Remarks |

| 29th Infantry (RO) |

NG & AR |

Honolulu, Hawaii |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 30th Armored |

NG |

Jackson, Tenn. |

1 |

2 |

|

|

|

| 30th Infantry |

NG |

Clinton, S.C. |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 31st Armored |

NG |

Northport, Ala. |

1 |

2 |

|

|

|

| 32d Infantry (M) |

NG |

Milwaukee, Wisc. |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 33d Infantry |

NG |

Chicago, Ill. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 36th Airborne |

NG |

Houston, Tex. |

No assigned battalions |

| 39th Infantry |

NG |

Little Rock, Ark. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 41st Infantry (RO) |

NG |

Portland, Oreg. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 45th Infantry |

NG |

Edmond, Okla. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 48th Infantry (M) (RO) |

NG |

Macon, Ga. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 53d Infantry |

NG |

Tampa, Fla. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 58th Infantry |

NG |

Pikesville, Md. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 67th Infantry (M) |

NG |

Lincoln, Neb. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 69th Infantry |

NG |

Topeka, Kans. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 73d Infantry |

NG |

Columbus, Ohio |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 81st Infantry (M) |

NG |

Seattle, Wash. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 92d Infantry |

NG |

San Juan, Puerto Rico |

4 |

|

|

|

|

| 116th Infantry |

NG |

Staunton, Va. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 149th Armored |

NG |

Bowling Green, Ky. |

No assigned battalions |

| 155th Armored |

NG |

Tupelo, Miss. |

1 |

2 |

|

|

|

| 157th Infantry (M) |

AR |

Horsham, Pa. |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

| 172d Infantry |

RA |

Fort Richardson, Alaska |

l |

1 |

1 |

|

Special Mission |

| 187th Infantry |

AR |

Fort Devens, Mass. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 193d Infantry |

RA |

Fort Kobbe, Canal Zone |

|

2 |

1 |

|

Special Mission |

| 194th Armored |

RA |

Fort Knox, Ky. |

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

| 197th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Benning, Ga. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 205th Infantry |

AR |

Fort Snelling, Minn. |

|

|

|

3 |

|

| 218th Infantry (M) |

NG |

Newberry, S.C. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 256th Infantry (RO) |

NG |

Lafayette, La. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

-

- [369]

- reserves continued to suffer major recruiting problems. When planning for

the three new Regular Army divisions, some Army Staff members and Secretary

of the Army Howard Callaway had wanted to use an Army Reserve infantry brigade

as a round-out unit, but none of the component's brigades met the required

manning and equipment levels. As an alternative the staff considered moving

either the 157th or the 187th Infantry Brigade, or both, to the southern part

of the United States and shifting the 205th Infantry Brigade to the West Coast,

all areas where recruiting was thought to be better. But congressional opposition

stopped these proposals, and the units remained generally in their existing

areas.35

-

- Despite these difficulties, Forces Command wished to improve the readiness

of the Army Reserve brigades. At first it proposed reducing the number of

units, particularly in the northeast, the First U.S. Army's area, and in

February 1975 it inactivated a battalion in the 157th Infantry Brigade at

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Then, early in 1976, Maj. Gen. Henry Mohr, Chief

of the Army Reserve, submitted a brigade improvement plan that retained

the units in their recruiting areas but eliminated other units from the

areas to limit the competition for scarce personnel resources. As the Army

Reserve staff developed the plan, Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and

Plans (DCSOPS) Lt. Gen. Donald H. Cowles selected the 41st Infantry Brigade,

the only brigade with a northern Arctic mission, as the round-out unit for

the 7th Infantry Division. To replace the brigade in the contingency plans,

Mohr agreed to reorganize the 205th Infantry Brigade as a light unit. The

brigade assumed responsibility for the contingency mission on 4 July 1976.36

-

- As the Army National Guard and Army Reserve shouldered a more active role

in the Total Army's deterrence plans, the Army Staff developed a plan in

the mid-1970s to upgrade the effectiveness of brigade- and battalion-size

units. Known as the Affiliation Program, the initiative had three goals:

improving readiness; establishing a formal relationship between regular

and reserve units; and developing a system of priorities for manpower, equipment,

training, funding, and administrative resources. Within the program five

categories of combined arms brigades existed: round-out units, which gave

Regular Army divisions their full organizational structure; augmentation

units, which increased the combat potential of standard divisions; worldwide

deployable units, which needed assistance to meet deployment schedules;

special mission units, which served as theater defense forces; and units

to support the Army school system. Thus, each brigade in the reserves was

to have a mission and train for it in a "come-as-you-are for war"

mode, which was a far cry from mobilization planning that had existed before

and after World War II.37

-

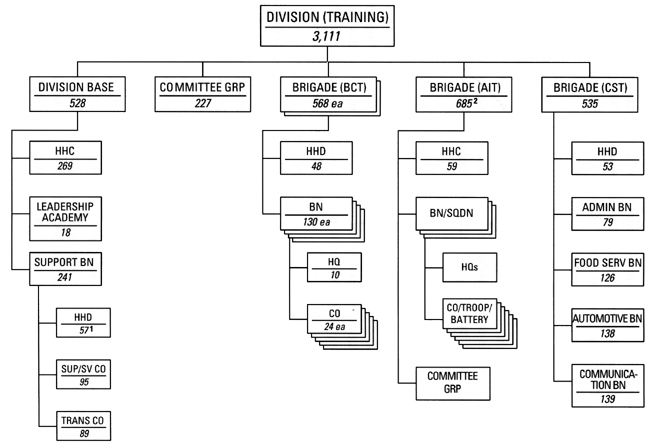

- In 1970 the Army had revised the tables of organization for the administrative

training division so that it could function more effectively in reserve

status. The division consisted of a division base, a headquarters and headquarters

company, a leadership academy, and a support battalion; a committee group;

and four brigades-two brigades for basic training, one for advanced individual

training, and one for combat support training (Chart 43). Basic combat training

brigades

- [370]

- Training Division, 1970

-

-

- 1 Includes the band.

- 2 Structure of the Advanced Individual Training brigade varied depending

upon the type of training (infantry, armor, reconnaissance, field artillery,

or engineer) offered.

-

- [371]

- and the committee group underwent little change, but significant modifications

were made in both advanced individual training and combat support training

brigades. The composition of the advanced individual training brigade varied

with the type of training (infantry, armor, reconnaissance, artillery, or

engineer) offered, and the combat support training brigade was reorganized

to consist of administrative, food service/supply, automotive, and communications

battalions. Upon mobilization the division could train between 12,500 and

14,000 enlisted personnel, depending upon the type of training provided by

each brigade. All thirteen training divisions had adopted the tables by the

end of 1971.38

-

- Two years later, seeking again to improve readiness of the Army Reserve

units, Forces Command inactivated some training division elements. Advanced

individual training brigades in the 76th, 78th, 80th, 85th, and 91st Divisions

and the combat support training brigades in the 89th and 100th Divisions

were inactivated and the spaces used to organize "mini" maneuver

area commands. The new commands planned, prepared, conducted, and controlled

company and battalion exercises for the reserves.39

-

- As in other reserve units, recruiting difficulties caused undermanning

in some training units. In 1975 Forces Command inactivated the 89th Division.

The personnel formerly assigned to it were used to strengthen other Army

Reserve units and to organize the 5th Brigade (Training), an armor training

unit with headquarters at Lincoln, Nebraska, that consisted of one squadron

and two battalions. With the saving in personnel, a nondivisional Army Reserve

combat unit, the 3d Battalion, 87th Infantry, was organized at Fort Carson,

Colorado, to support the 193d Infantry Brigade in the Canal Zone.40

-

- The Army Reserve's 5th Brigade (Training) and the training divisions were

reorganized once again in late 1978. To save both time and money in training,

the active Army had earlier adopted the One Station Unit Training (OSUT)

program, under which recruits received both basic and advanced individual

training at the professional home of their arm or service. The program proved

successful, and Forces Command adopted it for the Army Reserve training

divisions. In addition, the revised structure allowed divisions to be tailored

for specific mobilization stations. To reflect these changes, the Department

of the Army published new tables of organization, which retained as the

division base a leadership academy and a support battalion but broke the

brigades and battalions down into cells that fitted together to meet specific

training requirements. Divisional training brigades no longer conducted

basic combat or advanced individual training but carried out both, the same

as in the Regular Army. The former divisional committee group and the committee

group from the combat support brigade evolved into a training command.41

-

- By October 1978 the Army was fielding the 24-division, 24-brigade force

that Abrams had envisaged five years earlier. But organizational developments

had been eclipsed by even deeper changes in the fabric of the Army. Prior

to its

- [372]

- withdrawal from Vietnam, the Nixon administration had adopted an all-volunteer

force and imposed cuts in money and personnel. To make up for these losses,

Army leaders drew the Regular Army and reserve components closer together,

first through the round-out and then though the affiliation programs. The

Army could no longer enjoy the luxury of general-purpose forces. Every division

and brigade was either forward deployed or assigned a specific mission within

the current contingency and mobilization plans. The Regular Army's special

mission combined arms brigades included the 193d Infantry Brigade in the

Canal Zone and the 172d Infantry Brigade in Alaska. The 194th Armored and

197th Infantry Brigades served both as Strategic Army Force units and as

support troops for the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and the

Armor School at Fort Knox, Kentucky, in the training base. Changes in the

Total Army since the withdrawal from Vietnam stressed combat units at the

expense of support units. The nation did not have the resources for both.

- [373]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-