-

-

- The lightning war between the Arabs

and Israelis in 1973, when the Egyptian and Syrian armies lost more tanks

than the United States had in Europe at the time, caused the Army to rethink

its doctrine and the structure of its divisions and brigades. An examination

of the seventeen-day conflict led to new ideas about how to prepare for

war and how to fight. Known as the "Active Defense," the new doctrine

stressed defense as the principal mode of combat. Other factors embedded

in the new approach were the speed with which decisive actions would take

place and an awareness of the increased lethality of modern weapons on the

battlefield. Both considerations put added pressure on the Army to improve

the combat capabilities of forward-deployed active forces and the speed

with which effective reserve components units could be delivered to overseas

battlegrounds.2

-

- Since the Army was on the threshold

of adopting new equipment and weapons that increased mobility, firepower,

and maneuver, the Army's schools, commands, and agencies examined such issues

as military intelligence organizations; signal and aviation requirements;

and chemical, biological, and nuclear defense, seeking better ways to maximize

the new technology and not just providing "tag alongs" in existing

organizations. Fire support teams for artillery;

- [379]

- General Weyand

-

- bifunctional staffs (the unit commander

serving as a chief of staff with two deputies, one for operations and military

intelligence and the other for personnel and logistics); rearmament, refueling,

and maintenance in the forward area of the battlefield; and consolidation

of administration at the battalion level also came under scrutiny.3

-

- In March 1975 Chief of Staff General

Fred C. Weyand suggested to Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans

Lt. Gen. Donald H. Cowles that the structure of divisions should be reexamined.

Weyand was concerned that new technology had resulted in only "add

ons" to divisions, increasing their weight and complexity and decreasing

their overall flexibility. Cowles turned to General William E. DePuy, commander

of the U. S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), established in

1973 specifically to address training and doctrine issues, for his views.

DePuy assembled a group of officers from his command and the Army's schools

and centers to conduct a division restructuring analysis focused on finding

the optimum antiarmor capability for divisions. Among the areas considered

were the employment of the new armored vehicles coming into service and

the problems associated with exploiting new artillery and target acquisition

systems whose range had been greatly increased. 4

-

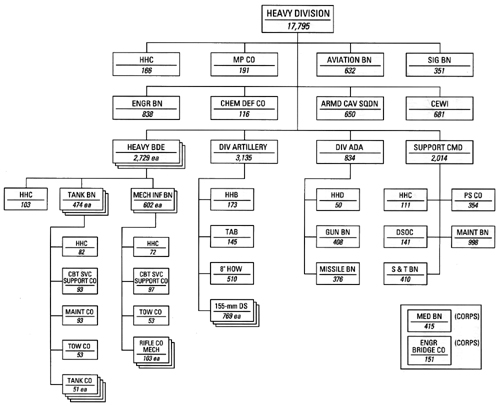

- The major product of the Division

Restructuring Study (DRS) was the "heavy division" (Chart 44),

an organization designed to replace both mechanized infantry and armored

divisions. Headed by Col. (later General) John Foss, from the Training and

Doctrine Command, the planning group believed that the principles underlying

the new organization could be applied to all divisions.

-

- The heavy division included three

brigades, each consisting of a permanent combat team of two mechanized infantry

and three tank battalions. Infantry battalions consisted of one combat support,

one TOW, and three small rifle companies; tank battalions, similar in structure

to the mechanized infantry units, fielded three tank companies and maintenance,

TOW, and combat support companies. A tank company had three tank platoons

with each platoon having only three tanks. The precise location of the TOW

antitank missile launchers posed the old problem of centralized versus decentralized

control for the planners, much as had the introduction of other new weapons

and equipment, such as the machine gun, tank, antitank gun, airplane, and

helicopter. For now they remained under control of the battalion.5

- [380]

- Heavy Division, Division Restructuring Study 1 March 1977

-

-

- [381]

- To increase firepower, the number

of 155-mm. howitzers in each direct support artillery battery was increased

from six to eight, and the number of firing batteries in a battalion rose

from three to four. The number of batteries in the 8-inch howitzer battalion

was also increased to four. Since the group foresaw a larger divisional combat

area in both width and depth, the artillery's counterfire (destroying enemy

artillery) capabilities moved from the corps level to the division, with a

target acquisition battery added to the division artillery to locate those

targets. A smaller cavalry squadron fielded only three ground troops, with

the air cavalry troop moved to a new divisional aviation battalion. For antiaircraft

defense, the study gave the heavy division an air defense artillery brigade

comprising two battalions, one for the forward area of the battlefield and

another for the rear.6

-

- With smaller divisional infantry

and armor battalions, planners envisioned integrating the combat arms at

the battalion rather than at the company level. Under the ROAD concept a

company team had been the principal combat formation. For example, a mechanized

infantry company was normally reinforced with engineers, forward artillery

observers, and possibly tanks, antitank weapons, and helicopters. But the

company commander who integrated these forces had no staff and probably

lacked the experience to achieve the most effective use of all these resources.

A change of focus therefore appeared necessary.7

-

- Combat support within the new division

also underwent radical changes. A combat electronic warfare intelligence

(CEWI) battalion was organized from military intelligence and Army Security

Agency resources. Consisting of an electronic warfare company and a ground

surveillance company, along with a headquarters and operations company,

the battalion greatly expanded the division's intelligence collection and

analysis capabilities. As noted, the reconnaissance squadron's aviation

troop was moved to a new divisional aviation battalion, which consolidated

the attack helicopter company and the division's command and control aviation

resources in one unit. All mess resources were grouped at battalion level,

and a personnel service company merged finance and personnel services into

one company, which was included in the support command. That command also

fielded a supply and transport battalion, a maintenance battalion, and a

support operations center. A chemical company provided the division with

smoke generating resources and the ability to assist in defense against

biological, nuclear, and chemical weapons. In the past no chemical unit

had existed in a division, and all units had been expected to defend against

those weapons as a primary responsibility. Finally, the study moved the

divisional medical battalion and the bridge company from the engineer battalion

to the corps level.8

-

- A field test of the new structure

at Fort Hood by a brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division in 1979 produced mixed

results. Lt. Gen. Marvin D. Fuller, the III Corps commander, who oversaw

the test, found the division overmanned and overequipped in many areas,

giving commanders resources to cover every possible deficiency or contingency.

He thought the additional costs in personnel and equipment would price the

division out of reach. He also found that radios had

- [382]

- proliferated to the extent that communications

were hampered rather than improved, that bifunctional staffs filtered information

needed by commanders, and that air defense coverage was still inadequate.

However, the test validated the belief that tank and mechanized infantry battalions

should be the focal point for the integration of the combined arms.9

-

- During the evaluation of the division

restructuring concept, the Army Staff approved selective improvements in

existing divisions based on lessons learned from the 1973 Arab-Israeli War.

A target acquisition battery was placed in the division artillery to identify

targets up to 50 kilometers in front of the forward edge of the battle area.

Chemical companies were added to divisions to provide nuclear, biological,

and chemical reconnaissance and decontamination support. Because of the

need to acquire and evaluate information about the enemy, divisional military

intelligence battalions of the CEWI type were organized beginning in 1979.

In the armored and mechanized infantry divisions, aviation resources were

again pooled to form aviation battalions. The airborne division was assigned

three antitank TOW companies, one for each brigade, while the infantry division

in Korea was assigned only a company. When the aerial field artillery battalion

was inactivated in the air assault division, antitank resources were concentrated

in an aviation battalion.10

-

- Along with upgrading existing divisions,

the Department of Defense directed the Army to increase its mechanized forces.

In September 1979 the 24th Infantry Division converted from infantry to

mechanized infantry, and the following year elements were assigned to the

previously unmanned 149th Armored Brigade in the Kentucky Army National

Guard, raising the number of brigades in the total force to twenty-five.

By 1980 the Texas Guard had eliminated its unfilled 36th Airborne Brigade,

using its personnel to organize a corps-level combat engineer battalion.

Planners also considered reorganizing all infantry divisions, except the

airborne and the airmobile forces, as mechanized units.11

-

-

- Before the 1st Cavalry Division

completed its evaluation of the heavy division in 1979, the new commander

of the Training and Doctrine Command, General Donn A. Starry, began to develop

another divisional concept that built upon the Division Restructuring Study.

From his experience as the V Corps commander in Europe, Starry believed

that Foss' Division Restructuring Study group had worked too quickly. Units

had conducted tests without proper training, and the opposing forces lacked

adequate knowledge of Soviet tactics. Therefore, he judged that the test

results could not be totally ascribed to deficiencies in tactics, leadership,

or organization. 12

-

- The Division Restructuring Study

had concentrated on the active defense, the lethality of the battlefield,

and the need to win the first battle, but Starry stressed the offense and

"central battle" where all aspects of firepower and maneuver,

air

- [383]

- General Starry

-

- and ground, would come together

over a wide area to produce a decisive action. He believed that analysis

of those elements in the battle area, including the range of weapons and

their rates of fire, the size of the opposing forces, the terrain over which

they would advance, and the speed of that advance, would permit development

of more effective operational concepts. In addition, he thought consideration

had to be given to "force generation," the task of concentrating

the combat power of the division for the central battle. These ideas evolved

into the "AirLand Battle" doctrine, which was published in 1982

in the revised Field Manual, 100-5, Operations.

13

-

- Analysis of combat within the framework

of the AirLand Battle concept led to the development of "Division-86,"

so named because 1986 was as far out as General Meyer and his advisers could

project the threat. Because of the importance of Europe to national security,

Division-86, like the Division Restructuring Study, emphasized a standardized

heavy division, which combined both armored and mechanized infantry divisions,

and focused on maximizing the new equipment entering the inventory. In October

1979, four months after General Edward C. Meyer became Chief of Staff, Starry

presented his Division-86 proposal, which Meyer approved in principle on

the 18th of that month. His final decision about fielding such a division

depended upon studies to be conducted for light divisions (infantry, airborne,

and airmobile), corps, and echelons above the corps level.14

-

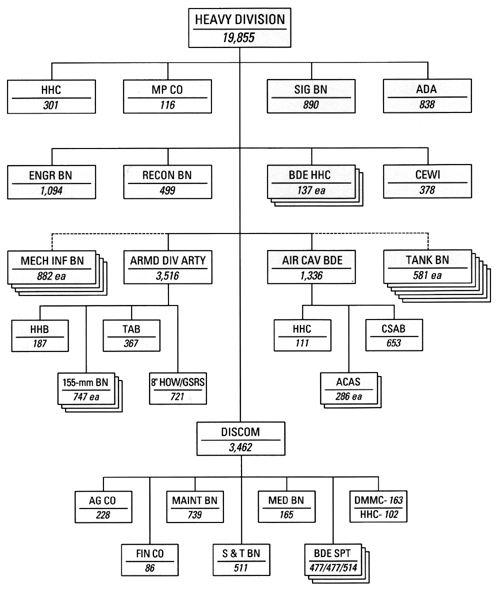

- Division-86, as presented to General

Meyer, retained the flexible ROAD structure. The new heavy division consisted

of a headquarters and headquarters company; three brigade headquarters;

a military police company; signal, air defense artillery, engineer, and

military intelligence battalions; a reconnaissance squadron; division artillery;

an air cavalry attack brigade; a division support command; and a number

of maneuver elements to be determined, possibly four or five mechanized

infantry battalions and five or six armor battalions. The division would

total approximately 20,000 officers and enlisted men (Chart

45).15

-

- Under the "come-as-you-are,

fight-as-you-are" approach to war, combat service support had to be

immediately available in the battle area. To meet the new

- [384]

- Heavy Division (Tank Heavy) As Briefed to General Meyer on 18 October

1979

-

-

- [385]

- General Meyer

-

- logistical requirements, the study

called for a radical reorganization of the division support command, primarily

to address the forward area of the battlefield. The command included a materiel

management center, adjutant general and finance companies, a supply and

transport battalion, a maintenance battalion, and three support battalions,

one for each divisional brigade. Support battalions, which were to "arm,

fuel, fix, and feed forward," included headquarters and headquarters,

supply, maintenance, and medical companies. A small medical battalion supported

the rest of the division. Planners had difficulty deciding whether to place

a chemical company at corps, division, or division support command level,

but gave it to the supply and transport battalion in the support command.16

-

- Evidence of fundamental change existed

within the combat arms. Each tank battalion consisted of a headquarters

element and four tank companies, and each tank company fielded three platoons

of four tanks each. Mechanized infantry battalions contained a headquarters

element along with one TOW and four rifle companies, with the riflemen to

be mounted on new Bradley infantry fighting vehicles. To counter the Soviet

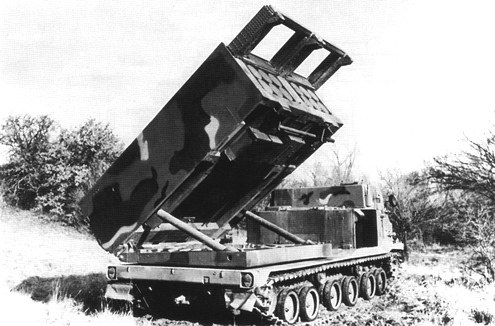

Union's high density of artillery and improved weapons, the Division-86

study, like its predecessor, significantly increased the division artillery.

It fielded three battalions of 155-mm. self-propelled howitzers organized

into three batteries, each having eight pieces; one battalion of sixteen

8-inch howitzers and nine multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS) mounted

on vehicles; and a target acquisition battalion. 17

-

- The reconnaissance squadron called

for three troops, each having two platoons equipped with cavalry fighting

vehicles similar to the Bradley fighting vehicle-and a platoon of motorcycles.

A new organization, an air cavalry attack brigade (later designated as an

aviation brigade), which resulted from the pioneer work of the 1st Cavalry

Division and the 6th Cavalry Brigade at Fort Hood and others, appeared in

the division to provide helicopters for an antitank role. Two attack battalions,

each consisting of four companies with six helicopters each, and a combat

support aviation battalion, which provided resources for command aviation,

aircraft maintenance, and the military intelligence battalion, made up the

brigade. The brigade fielded 134 aircraft.18

- [386]

-

- The Bradley fighting vehicle and, below, multiple launch rocket systems

-

-

- [387]

- Heavy Division, 1 October 1982

-

-

- Note 1 Variation 1-6, 4 mechanized infantry battalions (M113) 18,954.

- Variation 2-5, 5 mechanized infantry battalions (M113) 19,302.

- Variation 3-6, 4 mechanized infantry battalions (BFVS) 19,040.

- Variation 4-5, 5 mechanized infantry battalions (BFVS) 19,407.

- Variation 5-6, 4 mechanized infantry battalions (BFVS) 20,459.

-

- Note 2 Support battalions vary in the number of armor and mechanized

infantry forward support teams: 2 armor and infantry, 377; 2 armor and 2

infantry, 402; and 1 armor and 2 infantry , 363.

-

- [388]

- The distribution of air defense weapons

had haunted the planners. Because of the breadth and depth of the battlefield

one commander could not easily supervise air defense in the division's forward

and rear areas, with each area requiring unique weapons. An air defense artillery

brigade seemed to be one solution, but personnel constraints ruled it out.

Therefore, the division was authorized an air defense artillery battalion

outfitted with a mix of short-range (man-portable Stingers) and mid-range

(Chaparral) missiles, to be supplemented by the still experimental Sergeant

York gun system.19

-

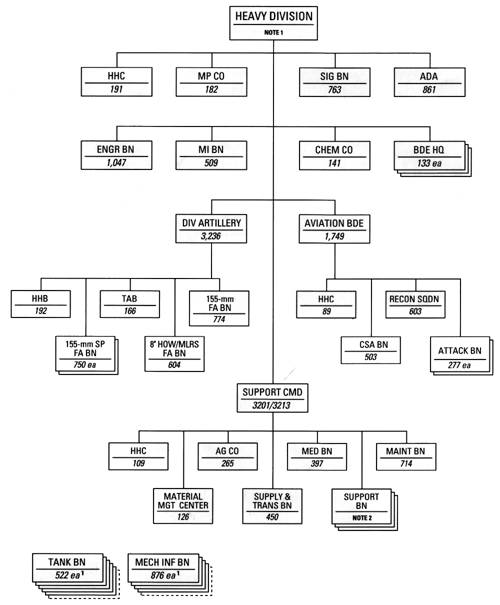

- The Training and Doctrine Command

published tables of organization and equipment for this second try at the

heavy division concept on 1 October 1982 (Chart 46). One set of tables covered

both the mechanized infantry division and the armored division, but with

five variations. Five or six armor and four or five mechanized infantry

battalions were to be assigned to an armored division, and a mechanized

infantry division was to have five armor and five mechanized infantry battalions.

Variations in the tables also covered different equipment, M60 tanks and

M 113 armored personnel carriers or the new M 1 Abrams tanks and Bradley

infantry fighting vehicles. Given the variations, the strength of heavy

divisions ranged between 19,000 and 20,500 officers and enlisted men.20

-

- The published tables differed somewhat

from the proposed heavy division that Meyer had approved three years earlier.

Cavalry fighting vehicles replaced tanks in the reconnaissance squadron,

and the squadron, consisting of two ground and two air troops, had no motorcycles.

Rather than being a divisional unit, it was a part of the aviation brigade.

The finance unit moved to the corps level, and the reorganized military

intelligence battalion fielded electronic warfare, surveillance, and service

companies. In the support command, the medical battalion reappeared, but

the chemical company was returned to divisional level, and the target acquisition

element was reduced to a battery.21

-

- The Army faced complex problems

in fielding Division-86. Over forty major weapons or new pieces of equipment

needed to be procured, and some were still in developmental stages. Doctrinal

literature and training programs required revision, and budgetary limitations

had to be considered. The solution approved by the Army Staff, as in the

past, was to adopt the heavy division concept but with interim organizations

using obsolete equipment until new weapons and equipment were available.

Delivery of many new items was expected to begin in 1983. Therefore, organizational

and equipment modernization was to begin in January of that year. The number

of maneuver elements for a heavy armored division was set at six armor and

four mechanized infantry battalions, while that for a heavy mechanized infantry

division was placed at five armor and five mechanized infantry battalions.22

-

- The Army also faced another problem

in fielding the new heavy division, a shortfall in personnel. The Training

and Doctrine Command estimated that a strength of 836,000 was required to

field Army-86, but only 780,000 was authorized for the foreseeable future.

Therefore to provide manpower spaces for mod-

- [389]

- ernizing the forces in Germany,

the 4th Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, was inactivated in Europe in 1984

along with other units throughout the Army. Shortly thereafter the modernization

plan went awry. Because of various problems involved in funding and procuring

equipment, the Army leadership slipped the completion date for modernizing

heavy divisions to the mid-1990s.23

-

- Early in the planning process for

modernizing divisional forces, Meyer also decided to adopt a new regimental

system. It was to address one aspect of the "hollow Army" (the

problem of having sufficient personnel and equipment to support and sustain

the forward-deployed Army), unit cohesion.24

Patterned after the Combat Arms Regimental System (CARS), the new United

States Army Regimental System assigned each armor, air defense artillery,

cavalry, field artillery, and infantry regiment -later aviation regiments

and special forces 25

were added-a home base from which regimental elements would rotate between

continental and overseas assignments. A soldier could affiliate with a regiment

and expect to serve in it for most of his or her career. By necessity the

new system broke traditional regimental associations with divisions since

fewer regiments could be accommodated in the system because of the linking

of elements between overseas and continental stations. Meyer believed that

the benefits of unit cohesion outweighed the loss of divisional affiliation.

He tied implementation of the new regimental system to modernization of

the force. By 1985 implementation of the regimental system was separated

from force modernization because of production delays, and unit rotation

was abandoned because of personnel turbulence and its adverse effect on

readiness. Nevertheless, designating regiments as part of the system continued,

paced by the number of flags that the US. Army Support Activity, Philadelphia,

could manufacture each month. The flags were needed when the battalion designations

were changed.26

-

-

- In 1979, when Meyer had approved

the heavy division, he also had directed Starry to standardize infantry,

airborne, and airmobile divisions-now called "light divisions."

Meyer, who opposed the total heavy force envisioned by Department of Defense

planners, wanted the Training and Doctrine Command to focus on the infantry

division; airborne and airmobile divisions were to be considered later.

He particularly wanted to know if the infantry division could be designed

to move and fight in contingency areas, such as the Asiatic rim, and still

have sufficient resources to delay and fight Soviet forces in Central Europe.

This question posed the dilemma that had plagued the airborne division community

since World War 11-how to give a unit strategic mobility and still have

it possess the firepower and the resources to sustain itself in combat.

Meyer thought the answer to the problem lay in the use of new technology,

which included advanced radar, intelligence, and satellite resources; containerized

food and equipment; lightweight, high power communications; new lightweight

vehicles; highly accu-

- [390]

- rate and powerful, but lightweight,

weapons; advanced helicopters; and other developments. Two international

events in 1979, the widening of the conflict between the Soviets and the

Afghans and Iran's seizure of American hostages, spurred the need for light,

versatile units.27

-

- An effective structure for the "non-heavy"

infantry division, however, proved elusive. Initially Starry set restrictions

on the division. Its size was not to exceed 14,000 soldiers, it was to be

without organic tank or mechanized infantry units, and it was to be deployable

in Air Force C-141 aircraft. After four tries and a relaxation of the strength

requirement, Starry recommended a division of 17,773 officers and enlisted

men, which Meyer approved for further development and testing on 18 September

1980.28

-

- As planners developed various ideas

for a light division, the Army Staff selected the 9th Infantry Division

at Fort Lewis, Washington, to serve as a "test bed," or a field

laboratory, for equipment, organization, and operations. One objective was

to shorten the equipment developmental cycle typically from five to seven

years-which had frustrated Meyer and others. Although Meyer obviously wanted

the division to experiment with new equipment, difficulties in funding hobbled

the effort from the start. Some of these problems were overcome through

the direct intervention of the Army Staff, but others were never surmounted.

In 1982 Meyer thus changed the emphasis of the 9th Division's mission from

testing highly technical equipment to developing innovative organizational

and operational concepts. The result was the design of a motorized division

of 13,000 men and capable of being airlifted anywhere in the world. Before

the 9th Infantry Division completed its new assignment, however, the Army

set off in a new direction for the light division.29

-

-

- By 1983 planners had reassessed

the nature and direction of world events and the types of conflicts that

could be expected. As Meyer saw a need for a balance between heavy and light

divisions, so did his replacement, Chief of Staff General John A. Wickham.

The successful operations of the British in the Falkland Islands, the Israelis

in Lebanon, and the United States in Grenada all drove home the point that

credible forces did not have to be heavy forces. To have light divisions

within the Army's limited resources, Wickham ordered the replacement of

the 16,000-man standard infantry division with a new light infantry unit

of about 10,000 men and the adaptation of light concepts to airborne and

airmobile divisions. He also wanted the design applied to the motorized

division under development at Fort Lewis. Furthermore, Wickham desired light

divisions to have an improved "tooth-to-tail" (i.e., combat strength

to logistics) ratio and to be deployable three times faster than existing

infantry divisions. With these changes he anticipated that the corps would

be strengthened and made the focus of the AirLand Battle doctrine.30

- [391]

- 9th Infantry Division "dune buggy" used in training

-

- Under Wickham's guidance the Army

specified that corps were to plan and conduct major operations, while divisions

were to concentrate on the tactical battlefield. The revised Field Manual

100-5, Operations, of 1986 defined the corps as the Army's largest

tactical unit. Tailored for a particular theater and mission, the corps

was to contain all combat, combat support, and combat service support required

for sustained operations. In addition to various types of divisions, the

corps was to have available an armored cavalry regiment; field artillery,

air defense artillery, engineer, signal, aviation, and military intelligence

brigades; and a military police group. Infantry and armored brigades and

psychological operations, special operations forces, and civil affairs units

could be attached as needed. When organized for a particular theater and

mission, the corps was thus to be a relatively fixed organization with area

as well as combat responsibilities. The newly defined corps was really a

throwback to the beginning of the century when Field Service Regulations

described a prototype corps.31

-

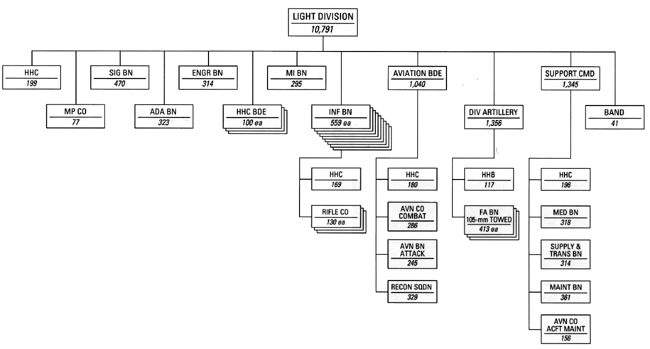

- Wickham's guidance resulted in the

development of units for the "Army of Excellence." 32

Within that rubric, the tables of organization and equipment called for

a 10,220-man light infantry division, which comprised a headquarters and

headquarters company; a military police company; signal, air defense artillery,

and engineer battalions; three brigade headquarters; nine infantry battalions;

division artillery; an aviation brigade; a support command; and a band.

Shortly thereafter a military intelligence battalion was added and additional

personnel autho-

- [392]

- General Wickham

-

- rized for the support command, which

raised the division's strength to 10,791 (Chart 47). All men and

their equipment were transportable in fewer than 550 C-141 sorties in less

than four days, a key feature in Wickham's guidance for the design of the

light division.33

-

- The light division greatly improved

the ratio of combat troops to support personnel. Infantry battalions fielded

three rifle companies and a headquarters company, a total of 559 officers

and enlisted men. The battalion headquarters company included a "footmobile"

reconnaissance platoon (no vehicles in it), an antiarmor platoon (four TOW

launchers), and a heavy mortar platoon (four 4.2-inch mortars). The only

vehicles in the battalions were the new "high mobility multi-purpose

wheeled vehicles" (HMMWVs, or "Hummers") and motorcycles.

Brigades provided mess and maintenance for battalions. The division artillery

consisted of three towed 105-mm. howitzer battalions, three batteries with

six howitzers each and one battery of 155-mm. howitzers fielding eight pieces.

A command aviation company, an attack helicopter battalion, and the reconnaissance

squadron comprised the aviation brigade. The air defense artillery battalion

fielded 20-mm. multibarrel, electrically driven Vulcan guns and the Stinger

missiles fired from a shoulder position, and the engineer battalion had

no bridging equipment. Support elements followed the functional ideas of

ROAD, with the division having a maintenance battalion, a supply and transport

battalion, a medical battalion, and a transportation aircraft maintenance

company, along with the command headquarters and materiel management center.

Support troops totaled about 1,300 men.34

-

- The light division met several needs

of the Army. It cost less and was simpler to maintain and support than the

heavy infantry division. It was well suited for rear area operations if

provided with air and ground transport and could easily adapt to urban operations,

heavily forested or rugged areas, and adverse weather conditions-all circumstances

found in Western Europe. Easily deployed, the division enhanced the Army's

strategic response options. The division's weaknesses included lack of organic

ground and air transport and an inability to face heavy forces in open terrain

because it lacked armor. Also, the division was vulnerable to heavy artillery,

nuclear, and chemical attacks and had only minimal

- [393]

- Light Division, 1 October 1985

-

- [394]

- indirect fire support. To compensate

for those deficiencies, the division was to look to the corps for reinforcements.35

-

- Plans to introduce light divisions

sent reverberations throughout all Regular Army divisions since there was

to be no increase in strength. Wickham directed reductions in the size of

heavy divisions to about 17,000 officers and enlisted men, with armored

divisions maintaining six armor and four mechanized battalions while mechanized

divisions continued to field five armor and five mechanized infantry battalions.

Cuts were therefore made in the combat support and service support elements.

As noted, the motorized division was limited to 13,000 men. He ordered the

reorganization of the 7th Infantry Division at Fort Ord and of the 25th

Infantry Division at Schofield Barracks as light divisions without round-out

brigades and the activation of the 10th Mountain Division at Fort Drum,

New York, and of the 6th Infantry Division at Fort Richardson, Alaska. The

10th was to have a Guard round-out brigade, and the 6th was to draw its

round-out units from both the National Guard and the Army Reserve.36

-

- With the plans to reorganize two

standard infantry divisions as untested light divisions, the Defense Department

decided to add another mechanized infantry division to the National Guard

force. In August 1984 the Guard's 35th Infantry Division, organized from

three existing brigades, returned to the active rolls under the new tables

as a mechanized division. Five states-Colorado, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri,

and Nebraska-contributed units to the division, including a mechanized infantry

brigade each from Kansas and Nebraska and an armored brigade from the Kentucky

National Guard. The headquarters of the new mechanized infantry division

was at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. To preclude the command and control problems

that some multistate divisions experienced after their reorganizations in

1967 and 1968, the five states supporting the division agreed that a division

council (the adjutant generals from the five states) was to select the division

commander and key personnel, who would serve a maximum of three years.37

-

- The 7th Infantry Division began

to transition to light division structure in 1984, and it was followed by

the conversion of the 25th Infantry Division and the activation of the 10th

Mountain and 6th Infantry Divisions. Because Fort Drum lacked facilities

to house even a small division, one Regular Army brigade of the 10th was

stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia, for three years. A new brigade, the

27th Infantry Brigade from the New York Army National Guard, completed the

10th. The 172d Infantry Brigade in Alaska was inactivated, and its personnel

provided the nucleus for the 6th Infantry Division. To retain an airborne

capability in Alaska, one company in each of the initial three infantry

battalions assigned to the 6th remained airborne qualified. Eventually all

airborne assets were concentrated in one divisional battalion. Although

the chief of Army Reserve agreed to have the 205th Infantry Brigade round

out the 6th Infantry Division, the Regular Army still lacked all the resources

to complete the division. Therefore, additional round-out units from the

Alaska Army National Guard and the Army Reserve were assigned. The 6th Division,

howev-

- [395]

-

- Winter training, 205th Infantry Brigade, 1986; below, 29th Infantry

Division reactivation ceremony, 1985.

-

-

- [396]

- er, never met the approved design

for a light division, as one light infantry battalion was not organized because

of the want of resources.38

-

- In addition to the Regular Army

divisions, the Department of Defense authorized the National Guard to organize

one light division, raising the total number of such divisions to five.

The 29th Infantry Division returned to the active force in the Maryland

and Virginia Army National Guard as a light division in 1985. Resources

from the 58th and 116th Infantry Brigades provided the nucleus for the new

division, which was headquartered at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. With the activation

of light infantry divisions, the number of divisions in the force rose to

28 (18 Regular Army and 10 National Guard) and the number of brigades fell

to 23 (16 in the National Guard, 4 in the Regular Army, and 3 in the Army

Reserve).39

-

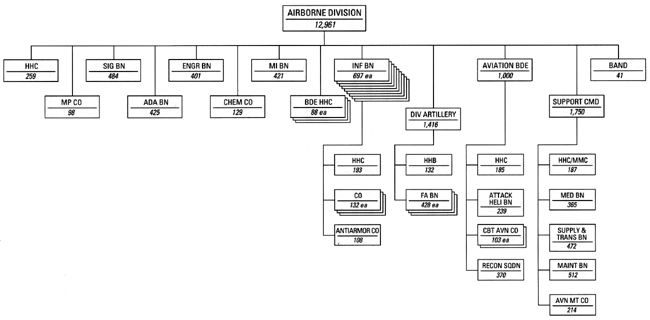

- As part of the Army of Excellence

program, Wickham's directive included cutting and standardizing airborne,

airmobile, and motorized divisions. As a result, the Training and Doctrine

Command published tables for a smaller airborne division, with its strength

plummeting from over 16,000 officers and enlisted men to approximately 13,000

(Chart 48). The new division was built on the light division base

with three brigade headquarters and nine infantry battalions as its major

components. However, it was stripped of both its armor battalion and its

separate TOW equipped infantry companies. Each infantry battalion consisted

of a headquarters and headquarters company, three rifle companies, and an

antitank company fielding five platoons, each equipped with four TOWs. The

one divisional addition, an aviation brigade, contained the reconnaissance

squadron, an attack helicopter battalion, and two combat aviation companies.

The target acquisition battery was eliminated from the division artillery,

and its three 105-mm. howitzer battalions were organized similarly to those

in the light division. No 155-mm. howitzers were assigned.40

-

- The greatest personnel economy in

the airborne division took place in the support command. It embodied a headquarters

and headquarters company; a materiel management center; medical, supply

and transport, and maintenance battalions; and an aviation maintenance company,

a total of about 1,750 soldiers rather than 2,500. Military police and chemical

companies and signal, military intelligence, air defense artillery, and

engineer battalions completed the airborne division. As in the light infantry

division, it had to be reinforced from corps level when engaged in sustained

operations. The 82d Airborne Division began adopting the new structure during

fiscal year 1986 and completed it the following year when the quartermaster

airdrop equipment company, which had been a nondivisional unit at Fort Bragg

since 1952, was added to the supply and transport battalion, almost doubling

its size.41

-

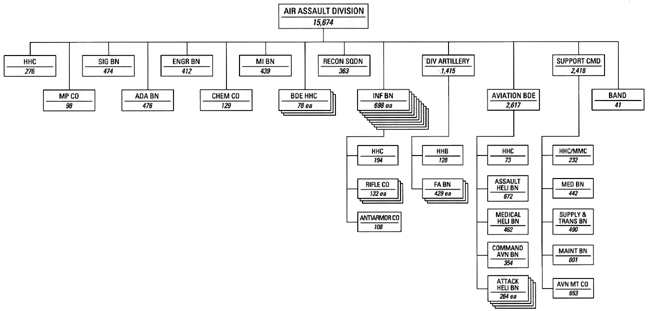

- Along with the airborne division,

the Training and Doctrine Command standardized the air assault division,

which was decreased by about 25 percent (Chart 49). It also was similar

to its old organization, but with a light division base. The division consisted

of three brigades, nine airmobile infantry battalions, division artillery,

a support command, and divisional troops. The one exception was the

- [397]

- Airborne Division, 1 April 1987

-

- [398]

- Air Assault Division, 1 April 1987

-

- [399]

- replacement of the aviation group

by an aviation brigade; the latter consisted of a command aviation battalion,

a combat aviation battalion, a medium aviation battalion, and four attack

aviation battalions. Artillery units were patterned after those in the airborne

division, having three 105-mm. towed howitzer battalions, and the support

command retained medical, supply and transport, and maintenance battalions,

along with an aviation maintenance battalion. The reconnaissance squadron

had a headquarters and four troops plus a long-range surveillance detachment.

The latter was a military intelligence unit manned by infantrymen who were

dependent on the cavalry squadron for transportation; doctrinally its location

created a problem, and the planners had no easy solution for its position

within the division. Each air assault infantry battalion fielded three rifle

companies and an antiarmor company.42

-

- In 1986 Forces Command began to

phase the new structure into the 101st Airborne Division; by 1990, however,

the Training and Doctrine Command changed the aviation brigade. The reconnaissance

squadron, which had been a divisional element, moved to the brigade, which

fielded one command, one medium, two assault, three attack battalions, along

with the reconnaissance unit. A fourth attack battalion was planned for

the brigade, but not active.43

-

- The one type of division that failed

to win a place in the Army of Excellence was the motorized infantry division

(also referred to as the middleweight rather than light division). Motorized

experiments conducted by the 9th Infantry Division had produced unsatisfactory

results because of funding problems created by going outside normal combat

development channels. The kinetic energy assault gun, the division's primary

weapons system, and the fast attack vehicle never got beyond the experimental

stage. In 1988 a reduction in the size of the Army forced the inactivation

of the 9th Division's 2d Brigade. To maintain the integrity of the division,

the 81st Infantry Brigade, from the Washington Army National Guard, was

assigned as a round-out unit. Also, Forces Command transferred the 1st Battalion,

33d Armor, a Regular Army unit, from I Corps to the division. Its new maneuver

element mix, including round-out units, consisted of two light attack infantry,

two mechanized infantry, three armor, and four combined arms (motorized)

battalions. The latter included two rifle companies and an assault gun company

equipped with TOWS mounted on HMMWVs.44

-

- With the reorganization of the Army

into heavy and light divisions, only the 2d Infantry Division in Korea and

the 26th, 28th, 38th, 42d, and 47th Infantry Divisions in the Army National

Guard remained organized under the dated standard infantry division's tables

of organization and equipment. Wickham exempted the 2d Infantry Division

from conversion to either the heavy or light configuration because of its

mission in Korea, the absence of a corps organization there, and Korean

augmentation assigned to it. Working with the Training and Doctrine Command,

Eighth Army devised a unique structure for the 2d that increased its firepower,

especially the artillery and the antiarmor capabilities, and provided a

mix of light and heavy maneuver battalions. The division was planned to

field

- [400]

- two armor, two mechanized infantry,

and two air assault infantry battalions, while the other maneuver elements

were to come from the Korean Army. By September 1990 the 2d Infantry Division

had adopted its Army of Excellence structure.45

-

- The reorganization of the National

Guard divisions under the Army of Excellence concepts, except for the 29th

Infantry Division, which returned to the active force in 1985 as a light

division, proved to be a challenging endeavor. In 1985 the 49th and 50th

Armored Divisions and 35th and 40th Infantry Divisions were reorganized

as heavy divisions with the same maneuver element mix as the Regular Army

divisions. Because of recruiting problems the areas that supported the Guard

divisions were expanded, usually to adjacent states. One exception to the

expansion was the 50th Armored Division, which was headquartered in New

Jersey but had the allotment of one of its brigades moved to the Texas Army

National Guard in 1988. Thus the future of the division in the force was

uncertain.46

-

- The Guard's five infantry divisions

carried on under modified versions of the "H" series tables of

organization and equipment, which were nearly twenty years old. Strengths

for those divisions ranged from 14,000 to 17,000. With uncertainty about

the need for more light divisions, the need for state troops, which the

local authorities were unwilling to lose, and the lack of funds, which did

not materialize, the reorganization of the units was held in abeyance. The

National Guard divisions were, however, truly a part of the "Total

Army." Because of concerns over sensitive equipment in the military

intelligence battalion, the Army Reserve provided that unit for each Guard

division except the 29th Infantry Division, which organized with its guardsmen.47

-

- As the Army modernized its heavy

divisions, it continued to revise their structure. In 1986 the 8-inch howitzers

were transferred from the heavy division to corps level, but the multiple-launch

rockets, organized as separate batteries, remained a part of the division

artillery. The same year the division's support command was reorganized.

Three forward support battalions (one for each brigade), a main support

battalion, and an aviation maintenance company replaced the divisional medical,

support and transport, and maintenance battalions in the support command.

The functions and services provided by the displaced units were performed

by mixed area support battalions. The divisional adjutant general company

was inactivated, and its functions moved to the corps level where they were

reorganized as a personnel service company, and the divisional materiel

management center was absorbed by the headquarters company in the support

command. The reorganization of the support command saved over 400 personnel

spaces. In the National Guard heavy divisions, the air defense artillery

battalions were eliminated because spare parts for antiquated M42 Dusters

were not available. On mobilization the corps was to provide antiaircraft

resources for these divisions.48

-

- By the end of 1989 the only Army

of Excellence structure that the Training and Doctrine Command had developed

for separate brigades was for the heavy one-armored and mechanized infantry.

Like the tables of organization and

- [401]

- equipment for heavy divisions, they

included variations for the types of equipment and the number of maneuver

elements that the brigades fielded. Each brigade, authorized approximately

4,100 soldiers, included a headquarters and headquarters company, engineer

and military intelligence companies, a cavalry reconnaissance troop, a field

artillery battalion (three batteries of six self-propelled 155-mm. howitzers

each), a support battalion, and a combination of armor and mechanized infantry

battalions.49

-

- The reorganization of reserve brigade

forces, both separate and round-out units, also became an ongoing process.

For the 9th Infantry Division (Motorized), the 1st Cavalry Division, and

5th and 24th Infantry Divisions the maneuver element mix of their National

Guard round-out brigades was increased from three to four battalions, two

armor and two mechanized infantry. The light round-out brigades for the

6th Infantry and 10th Mountain Divisions continued to field three maneuver

battalions. The 27th Infantry Brigade, rounding out the 10th Mountain Division,

however, did not have all of its brigade base units. Five other heavy brigades

in the National Guard were also organized under Army of Excellence tables,

while the eight National Guard and the two Army Reserve infantry brigades,

like the National Guard infantry divisions, employed a mishmash of old and

new structures. Although eight Guard infantry brigades were not modernized,

each had the same number of assigned maneuver elements, except for the 92d

Infantry Brigade in Puerto Rico, which had four rather than three infantry

battalions. The 157th Infantry Brigade, the only mechanized infantry brigade

in the Army Reserve, fielded only three maneuver elements as did the 187th

Infantry Brigade.50

-

- The Regular Army brigades continued

to lack uniformity. In 1984 Forces Command reorganized the 194th Armored

and 197th Infantry Brigades under the heavy brigade configuration. The 193d

Infantry Brigade, the special mission brigade in Panama, was reorganized

as a light unit consisting of two infantry battalions (one being airborne

qualified), a field artillery battery, and a support battalion. The 3d Battalion,

87th Infantry, from the Army Reserve was identified as a round-out unit

for the brigade. An additional table of organization brigade was added to

the Regular Army in 1983 when United States Army, Europe, and Seventh Army

organized the Berlin Brigade under a standard separate infantry brigade

table, which provided resources for improved command and control of its

assigned units. It had three infantry battalions, a field artillery battery

(eight 155-mm. self-propelled howitzers), a tank company, and a newly activated

support battalion.51

-

- The cellular organization adopted

in 1978 for the twelve training divisions and two training brigades (a new

brigade, the 4024, had been organized in 1985 for field artillery training)

in the Army Reserve created problems, particularly in accounting for the

personnel assigned to the units. Some positions were authorized within divisional

tables of organization and equipment cells and others were provided for

as a part of the United States Army Reserve centers to which the divisions

and brigades were assigned. Between the two documentation sources,

- [402]

- Forces Command found it difficult

to tell which parts of the reserve centers were dedicated to support the

training units. The command eventually recommended a solution, which the

Army Staff approved on 11 December 1986. The training divisions and brigades

were to be reduced to zero strength to keep the units active and then backfilled

using tables of distribution and allowance. The change allowed Forces Command

to identify specific billets for each division, brigade, and reserve center

for its specific mission. The lineage, honors, and history of the divisions

and brigades continued to be represented in the reserve forces. Units began

adopting the system in September 1988 and completed the process September

1990.52

-

-

- With its light and heavy divisions

and brigades, the Army of Excellence reorganization was expensive, and ultimately

the high cost forced the Army to move in a new direction during the late

1980s. All elements of the military establishment, Army, Navy, Marine Corps,

and Air Force, competed for modernization monies, which helped drive the

national debt to unacceptable levels. In 1988, as a part of its share in

reducing defense costs, the Army inactivated one brigade from the 9th Infantry

Division, as already noted, and replaced it with the 81st Infantry Brigade

from the Washington Army National Guard. The following year the 2d Brigade,

4th Infantry Division, was inactivated, creating a gap that was closed by

the 116th Cavalry Brigade from the Idaho, Oregon, and Nevada National Guard.

The Guard's 116th and 163d Armored Cavalry regiments had been reorganized

by 1989 as armored brigades because no requirement existed for those regiments

in the force. By the end of fiscal year 1989 the Army had twenty-eight divisions

and twenty-five brigades (Tables 37 and 38) in the active Army and

reserve components combined.53

-

- During the summer of 1989 the Warsaw

Pact began to disintegrate. Economic and social issues fired the changes,

and nations in Eastern Europe wrenched control of their affairs from the

Soviet Union. By the end of the year most Soviet client states were set

on a path of self-determination. Given this change, the rationale for the

North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the basis for having United States forces

forward deployed in Europe, and much of the Army doctrine for fighting the

AirLand Battle came under close scrutiny.

-

- Before any reassessment of the defense

establishment in light of these events was completed, in December 1989 the

Army was called upon to deploy the 7th Infantry Division and the 1st Brigade,

82d Airborne Division, to Panama as a part of Operation JUST CAUSE, an effort

to restore democracy to that Latin American republic. Several months later

American divisions and brigades participated in Operation DESERT SHIELD/DESERT

STORM, a multinational endeavor to halt Iraqi aggression in Southwest Asia

and to restore the independence of Kuwait (Table 39 lists the divisions

and brigades that deployed to Southwest Asia).

- [403]

- Divisions, 1989

-

| Division |

Component |

Location of Headquarters |

Maneuver Battalion |

Round-out Unit |

| Inf |

Mech |

Ar |

Abn |

AAST |

LI |

CAB |

| 1st Armored |

RA |

Ansbach,

Germany |

|

4 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1st Cavalry |

RA |

Fort Hood,

Tex. |

|

2 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

155th Armored

Brigade |

| 1st Infantry |

RA |

Fort Riley,

Kans. |

|

4 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

2d Bn, 136th

Infantry |

| 2d Armored |

RA |

Fort Hood,

Tex. |

|

4 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

2d Bn, 252d

Armor |

| 2d Infantry |

RA |

Korea |

|

2 |

2 |

31 |

|

|

|

|

| 3d Armored |

RA |

Frankfurt, Germany |

|

4 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3d Infantry |

RA |

Wuerzburg, Germany |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Carson,

Colo. |

|

4 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

2d Bn, 120th

Infantry |

| 5th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Polk,

La. |

|

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

256th Infantry

Brigade |

| 6th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Richardson,

Alaska |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

205th Infantry

Brigade |

| 7th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Ord,

Calif |

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

| 8th Infantry |

RA |

Bad Kreuznach,

Germany |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 9th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Lewis,

Wash. |

|

|

1 |

|

|

2 |

4 |

81st Infantry

Brigade |

| 10th Mountain |

RA |

Fort Drum,

N.Y. |

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

27th Infantry

Brigade |

| 24th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Stewart,

Ga. |

|

3 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

48th Infantry

Brigade |

| 25th Infantry |

RA |

Schofield

Barracks, Hawaii |

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

| 26th Infantry |

NG |

Buzzards

Bay, Mass. |

8 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 28th Infantry |

NG |

Harrisburg,

Pa. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 29th Infantry |

NG |

Fort Belvoir,

Va. |

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

-

- [404]

- TABLE 37-Continued

-

| Division |

Component |

Location of Headquarters |

Maneuver Battalion |

Round-out Unit |

| Inf |

Mech |

Ar |

Abn |

AAST |

LI |

CAB |

| 35th Infantry |

NG |

Fort Leavenworth,

Kans. |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 38th Infantry |

NG |

Indianapolis, Ind. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 40th Infantry |

NG |

Los Alamitos, Calif |

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 42d Infantry |

NG |

New York, N.Y. |

6 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 47th Infantry |

NG |

St. Paul, Minn. |

8 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 49th Armored |

NG |

Austin, Tex. |

|

4 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50th Armored |

NG |

Somerset, N.Y. |

|

4 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 82d Airborne |

RA |

Fort Bragg, N.C. |

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

| 101st Airborne |

RA |

Fort Campbell, Ky. |

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

-

- 1 One air assault battalion inactivated

in September 1990.

-

- [405]

- Brigades, 1989

-

| Brigade |

Component |

Location of Headquarters |

Maneuver Battalion |

| Inf |

Mech |

Ar |

Abn |

Lt Inf |

| 27th Infantry |

NG |

Syracuse, N.Y. |

|

|

|

|

3 |

| 29th Infantry |

NG |

Honolulu, Hawaii |

31 |

|

|

|

|

| 30th Armored |

NG |

Jackson, Tenn. |

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

| 30th Infantry |

NG |

Clinton, S.C. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 31st Armored |

NG |

Northport, Ala |

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

| 32d Infantry |

NG |

Milwaukee, Wisc. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 33d Infantry |

NG |

Chicago, Ill. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 39th Infantry |

NG |

Little Rock Ark. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 41st Infantry |

NG |

Portland, Oreg. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 45th Infantry |

NG |

Edmond, Okla. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 48th Infantry |

NG |

Macon, Ga. |

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

| 53d Infantry |

NG |

Tampa, Fla. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 73d Infantry |

NG |

Columbus, Ohio |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 81stInfantry |

NG |

Seattle, Wash. |

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

| 92d Infantry |

NG |

San Juan, Puerto Rico |

4 |

|

|

|

|

| 116th Cavalry2 |

NG |

Boise, Idaho |

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

| 155th Armored |

NG |

Tupelo, Miss. |

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

| 157th Infantry |

AR |

Horsham, Pa. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 163d Armored |

NG |

Bozeman, Mont. |

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

| 187th Infantry |

AR |

Fort Devens, Mass. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 193d Infantry |

RA |

Fort Clayton, Canal

Zone |

|

|

|

1 |

23 |

| 194th Armored |

RA |

Fort Knox, Ky. |

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

| 197th Infantry |

RA |

Fort Benning, Ga. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 205th Infantry |

AR |

Fort Snelling, Minn. |

3 |

|

|

|

|

| 218th Infantry |

NG |

Newberry, S.C. |

|

2 |

1 |

|

|

| 256th Infantry |

NG |

Lafayette, La. |

|

2 |

2 |

|

|

| Berlin |

RA |

Berlin, Germany |

3 |

|

|

|

|

-

- 1 One Army Reserve and two National

Guard Battalions.

- 2 Reorganization of the 116th Armored

Cavalry as the 116th Cavalry Brigade not complete.

- 3 One Army Reserve and one Regular

Army battalion.

-

- [406]

- Divisions and Brigades

in Southwest Asia, 1990-91

-

| Unit |

Home Station |

| 1st Armored Division (less1st

Brigade) |

Germany |

| 1st Cavalry Division (less

256th Infantry Brigade) |

Fort Hood, Texas |

| 1st Infantry Division (less

1st Infantry Division Forward) |

Fort Riley, Kansas |

| 1st Brigade, 2d Armored Division |

Fort Hood, Texas |

| 3d Brigade, 2d Armored Division |

Germany |

| 3d Armored Division |

Germany |

| 3d Brigade, 3d Infantry Division |

Germany |

| 24th Infantry Division (less

48th Infantry Brigade) |

Fort Stewart, Georgia |

| 82d Airborne Division |

Fort Bragg, North Carolina |

| 101st Airborne Division |

Fort Campbell, Kentucky |

| 197th Infantry Brigade |

Fort Benning, Georgia |

-

- The nation and the Army reached

a watershed in 1990 with the disintegration of Soviet Union and the deployment

of forces to Southwest Asia. Since the end of the conflict in Vietnam, national

leaders had focused on the countering of the Soviet menace, and the Army's

Division Restructuring Study, the Airland Battle doctrine, and the Army

of Excellence heavy divisions, first and foremost, had addressed that threat.

Although the need for other types of divisions and separate brigades was

recognized, limited resources bridled full implementation of the Army of

Excellence design. Aggression by the small Iraqi nation introduced a series

of new questions about the size, type, and location of division and separate

brigade forces needed. The answers to these questions are left to the future,

but an ever-changing world and ongoing revolution in weapons and information

technology will continue to challenge the designers of the Army force structure

in years ahead.

- [407]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-