Chapter VII:

The Defense Environment of the 1950s

The Secretary of Defense

under the National Security Act of 1947 had little authority over the three

armed services. The first Secretary of Defense, James V. Forrestal, in fact,

had been hoist by his own petard. As Secretary of the Navy he had helped convince

Congress that the new Secretary should have a bare minimum of authority over

the services and only a very small staff. As the first Secretary of Defense,

Forrestal found himself embarrassed and harassed by open interservice rivalries

which he lacked the authority to settle. Twice, in conferences with the joint

Chiefs at Key West in March 1948 and at Newport in September of the same year,

he thought he had negotiated an armistice only to discover that the services

interpreted these agreements in terms of their own parochial interests. Another

discovery was that he had little effective control over defense budgets either.1

Forrestal in 1948

recommended to the President amending the National Security Act of 1947 to provide

the Secretary of Defense with greater authority and control over the military

services. The Commission on the Organization of the Executive Branch of the

Government established by Congress in July 1947 under former President Herbert

C. Hoover agreed with the Secretary in its report. Acting on these recommendations

Congress passed the National Security Act amendments of 1949 (Public Law 216

of 10 August 1949) which redesignated the National Military Establishment as

the Department of Defense, provided the Secretary of Defense with a deputy and

three assistant secretaries, including a Comptroller, and created a nonvoting

chairman of the joint Chiefs of Staff. The service secretaries lost their seats

on the National Security Council,

[271]

their cabinet status,

and their direct access to the President but not to Congress.2

The National Security

Act amendments of 1949 had also granted the Secretary of Defense greater control

over financial management which he used to reorganize the military budgets along

functional lines. The impetus for the reform came from industrialists outside

the military establishment, in particular the Hoover Commission Task Force on

National Security Organization headed by Ferdinand Eberstadt, a New York investment

broker who had assisted Mr. Forrestal earlier in developing the Navy's unification

proposals.3

The Hoover Commission

in its recommendations for reforming federal administrative management to provide

greater executive control over operations had taken-up where President Roosevelt's

Committee on Administrative Management had left off ten years earlier. Before

then the traditional focus of administration generally and of budgets in particular

was honesty, efficiency, and economy epitomized in the Army's doctrine of accountability.

The Roosevelt Committee, opposed at the time by traditionalists, had inaugurated

a new period. of administration where the emphasis was on executive control

over operations through vertical integration along functional lines, management

engineering techniques for work measurement, and functional budgets. The Bureau

of the Budget took the lead in this movement. In the Army the leadership had

come from General Somervell and his Control Division. The demise of Army Service

Forces at the hands of the traditionalists

[272]

stalled the movement

within the Army until the Hoover Commission sparked its renewal, this time under

the leadership of the Comptroller of the Department of Defense.4

The Army's budget

reflected its fragmented organization. There were twenty-five major "projects"

or appropriations classifications based upon the technical services, each with

its own individual budget, which accounted for 80 percent of the funds spent

by the Army. (Table 1) Neither the Secretary of the Army nor the General

Staff possessed any effective control over these funds. Congressionally oriented

procedures for spending and accounting for appropriated funds also made financial

control difficult. The Army's various accounting systems only told Congress

how much of the funds in any appropriation had been committed or obligated,

not how much had been actually spent or when. They contained no information

on what happened to mat6riel or supplies after their purchase. The existence

at all levels of command of unfunded obligations, principally military pay,

and expendable items were added impediments to rational financial control.

Congress emphasized

the independence of the technical services in its traditional restrictions on

transferring funds among major appropriations categories. Technical service

chiefs could and did transfer funds freely among their various activities, functions,

and installations, but neither the Secretary nor the General Staff could legally

transfer funds among the several technical services or other staff agencies

without going to Congress for approval.

Given these conditions

there was no rational means of determining how much the Army's operations cost,

no means of distinguishing between capital and operating expenses in most instances,

and no means of determining inventory supplies on hand. Repeated requests for

deficiency appropriations each year made even control by Congress over spending

difficult.

Finally it was not

possible to correlate budgets and appro-

[273]

LIST OF MAJOR PROJECTS AND SUB-PROJECTS

INCLUDED IN FISCAL YEAR 1949 BUDGET OF THE ARMY MILITARY (ACTIVITIES) FUNCTIONS

Office of the Secretary of the Army

A. Contingencies of the Army

B. Penalty Mail-Military Functions

General Staff Corps

C. Field Exercises

D. National War College

E. Inter-American Relations-Department of the Army

Finance Department

F. Finance Service, Army

1. Pay of the Army

2. Travel of the Army

3. Expenses of Courts-Martial

4. Apprehension of deserters

5. Finance Service-for compensation to clerks and other employees of Finance

Department

6. Claims for damage to or loss or destruction of property, or personal

injury, or death

7. Claims of military and civilian personnel of the Army for destruction

of private property

G. Retired Pay, Army

Quartermaster Corps

H. Quartermaster Service, Army

1. Welfare of enlisted men

2. Subsistence of the Army

3. Regular supplies of the Army

4. Clothing and equipage

5. Incidental expenses of the Army

Transportation Corps

I. Transportation Service, Army

Signal Corps

J. Signal Service of the Army

Medical Department

K. Medical and Hospital Department

Corps of

Engineers

L. Engineer Service, Army

1. Engineer Service

2. Barracks and quarters, Army

3. Military posts

Ordnance Department

M. Ordnance Service and Supplies, Army

Chemical Corps

N. Chemical Service, Army

Army Ground Forces

O. Training and Operation, Army Ground

Forces

P. Command and General Staff College

[274]

TABLE I

LIST OF MAJOR PROJECTS

AND SUB-PROJECTS INCLUDED IN FISCAL YEAR 1949 BUDGET OF THE ARMY MILITARY (ACTIVITIES)

FUNCTIONS-Continued

United States Military Academy

Q. Pay of Military Academy

R. Maintenance and Operation, U.S. Military Academy

National Guard

S. National Guard

Organized Reserves

T. Organized Reserves

Reserve Officers' Training Corps

U. Reserve Officers' Training Corps

National Board for Promotion of Rifle

Practice, Army

V. Promotion of Rifle Practice

Departmental Salaries and Expenses

W. Salaries, Department of the Army

1. Office of Secretary of the Army

2. Office of Chief of Staff

3. Adjutant General's Office

4. Office of Inspector General

5. Office of Judge Advocate General

6. Office of Chief of Finance

7. Office of Quartermaster General

8. Office of Chief of Transportation

9. Office of Chief Signal Officer

10. Office of Chief of Special Services

11. Office of Provost Marshal General

12. Office of Surgeon General

13. Office of Chief of Engineers

14. Office of Chief of Ordnance

15. Office of Chief of Chemical Corps

16. Office of Chief of Chaplains

17. National Guard Bureau

Office of the Secretary

X. Contingent Expenses, Department

of the Army

Y. Printing and Binding, Department of the Army

Source: Cresap,

McCormick and Paget Final Report, 15 Apr 49, p. III-17.

priations with the military plans, missions,

functions, and operations of the Army as a whole.5

After investigating these conditions

Mr. Hoover told Congress that he and his committee thought the military budget

[275]

system had broken

down. The Army and Navy budget structures were antique. "They represent

an accumulation of categories arrived at on an empirical and historical basis.

They do not permit ready comparisons, they impede administration, and interfere

with the efficiency of the Military Establishment. Congress allocates billions

without accurate knowledge as to why they are necessary or what they are being

used for." Both Hoover and Eberstadt agreed that the efficient operation

of the Defense Department required a complete overhaul of the military budget

structure and its procedures and fiscal policies.

Hoover urged reorganizing

the budget "on a functional or performance basis, by which the costs of

a given function can be compared year by year . . . ." Eberstadt recommended

that the Secretary of Defense have full authority and control over the preparation

and expenditure of the defense budget, assuring "clear and direct accountability

to the President...and the Congress through a single official.6

Title IV of the National

Security Act amendments reflected the recommendations of the Hoover Commission

and the Eberstadt Committee on financial management. Section 401 established

the Office of Comptroller in the Department of Defense and delegated broad authority

to him over the financial operations of the department. The Comptroller was

to direct preparation of the department's budget estimates, including the formulation

of uniform terminology, budget classifications, and procedures. He was responsible

for supervising accounting procedures and statistical reporting. Section 402

provided for comptrollers in each of the three services responsible directly

to the service secretaries and acting in accordance with directions from the

Defense Department Comptroller. The fiscal, administrative, and managerial organization

and procedures of the several departments, it declared, should be compatible

with those of the Office of the Defense Department Comptroller.

[276]

Section 403 called

for adoption of "Performance" budgets and new accounting methods which

would "account for and report the cost of performance of readily identifiable

functional programs and activities, with segregation of operating and capital

programs." It also required the service budgets to follow a uniform pattern.

Section 405 provided for working capital funds to finance retail and industrial

activities within each service such as Quartermaster depots and Ordnance arsenals.7

Performance budgets

meant nothing until the new Department of Defense Comptroller identified what

functional budget classifications to adopt. The first Comptroller of the Department

of Defense was Wilfred J. McNeil who remained in this position for a record

ten years. He was intimately familiar with defense budgets and financial practices

as de facto Comptroller of the Navy since 1945, following similar

service in uniform during World War II. He helped Mr. Eberstadt prepare his

report on military financial management and participated in drafting Title IV

of the National Security Act amendments of 1949.

Mr. McNeil later said

"There were entirely too many fiscal masters; fiscal management was divorced

from management responsibility; and there were no clear lines of authority for

responsibility and management; it was all diffused. Money and responsibility

should parallel each other in any business operation-otherwise there can't be

any tight reins on spending. If the man responsible for operating something

has to account for where the money goes, he's naturally going to make sure it

isn't spent for something it should not be." 8

One of McNeil's first

reforms was the inauguration on 17 May 1950 of the new

performance budget with eight broad functional classifications in place of the

traditional technical service oriented budget. For the Army they were military

personnel, operations and maintenance, procurement and produc-

[277]

tion, research and

development, military construction, army national guard, reserve personnel requirements,

national guard military construction, and army civilian components.

With this one directive

McNeil wiped out the independent budgets of the technical services dating back

in some instances to the Revolution. The chiefs no longer would defend their

budgets before Congress. Instead this would be the responsibility of the several

General Staff divisions. Congressional restrictions on transferring funds among

appropriations would hamstring the technical services rather than the General

Staff. Although they would continue to spend the largest amount of the Army's

budget, the technical services would do so under the supervision and control

of several General Staff divisions.9

The General Staff

gained further control over technical service budgets through its membership

on a new Budget Advisory Committee (BAC) (Army Regulation 15-35, 2 October 1951)

. The technical services were not represented on this committee which passed

on their budget requests. Under the old system the General Staff had little

choice but to forward the technical services' requests. Under the new system

the technical services had to justify their budgets in detail before the BAC.

10

The Army's functional

budget was similar to those developed in modern industrial corporations to control

their operations. It told in detail what it cost to support the Army in terms

of men and material resources. It did not reveal the other side of the picture,

the cost of the Army's operations at home or abroad. It did not reveal the gap

which had grown, as General Marshall had warned, between American military commitments

and the resources available to meet them following World War II.

To close the gap both

the Hoover Commission and Cresap, McCormick and Paget had recommended the development

of an "Army Program System" that would translate strategic plans into

functional operating programs which in turn could be translated into the new

functional budget.

The Army accepted these recommendations

in principle

[278]

and on 12 April 1950

announced the inauguration of the new system which would assist in the alignment

of resources and military requirements. Theoretically the Army Programs were

intended to be concrete operational plans designed to translate JCS strategic

plans into action. They were to include a detailed time schedule for meeting

specified program objectives, the resources required in detail, and a means

of reviewing progress. The program cycle would contain three. phases: program

development, when plans would be translated into operating programs; program

execution, when they would be translated into budgets, later into appropriations,

and finally carried out; and program review and analysis. The department assigned

responsibility for program development to the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans,

for program execution to the Deputy Chief of Staff for Administration, and program

review and analysis to the Comptroller.11

Translating these

theoretical concepts into action required time to adjust and revise operating

programs in practical terms to reflect planning missions at one end and at the

other to relate as closely as possible to budget classifications. It also took

more time to educate all levels of the Army in the mechanics of the new system.

There were interruptions.

The Korean War pushed the new Program System into the background. Budget requests

to support the Korean War were developed in a series of "crash actions"

as deficiency appropriations requests in addition to the normal annual budget

requests. Deadlines imposed by the Korean emergency did not allow time to translate

plans into programs and then into budgets. It was not until after the

[279]

Korean armistice in

July 1958 that any attention could be paid to developing the new Program System.

It took two years

just to develop the "Program Budgets" themselves into sufficient detail

for submission to Congress. The element that caused the greatest difficulty

and required the most indoctrination was the program planning phase. The Army

was accustomed to submitting its budget request six months before the President

submitted his total budget to Congress and a year in advance of the fiscal year

for which the funds were requested. Under the Army Program System the cycle

for translating strategic plans into detailed operating programs began one year

ahead of the budget cycle or two years before the target fiscal year. The programs

in turn were based on JCS mid-range planning projected several years ahead of

the target year. The Joint Strategic Objectives Plan, as it was designated to

distinguish it from long-range planning estimates and short-range contingency

or capabilities planning, set forth concrete military requirements in terms

of major forces, strengths, facilities, and materiel. These became the Army

Strategic Objectives Plan developed for two years before the target fiscal year

that formed the basis for later developing Army Control Program Objectives.

Concrete Program Objectives came next, accompanied by instructions, operating

assumptions, and schedules for completing approved Control Programs in time

to prepare budget requests for carrying out the programs. The co-ordination

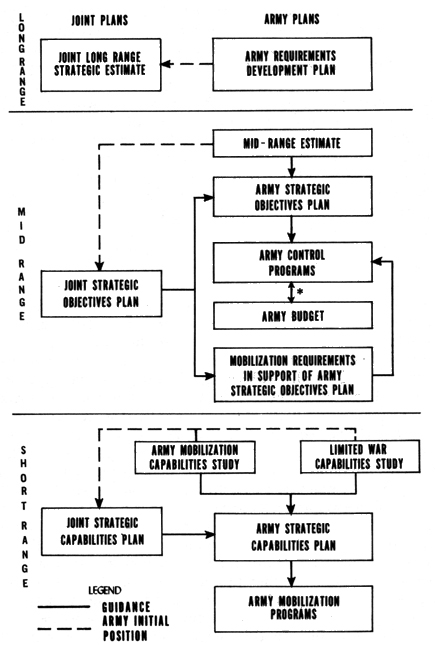

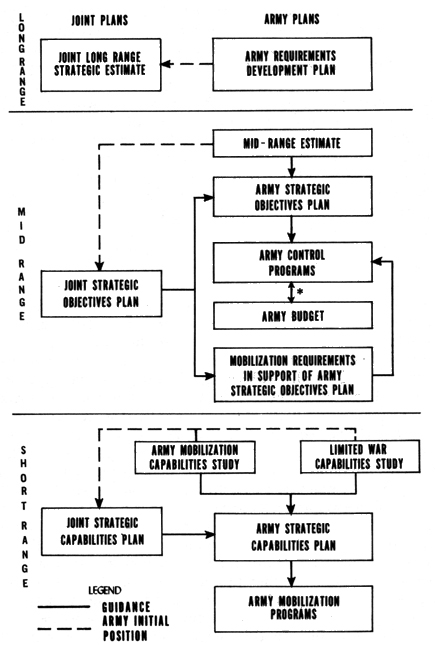

of plans and programs is indicated in Chart 24.12

Translating mission-oriented

strategic plans into functionally oriented operating programs and again into

functional budgets on schedule proved impossible. By the end of the decade the

gap between military requirements laid down in strategic plans and the resources

available in military appropriations was still enormous.13

The principal reason

for this gap was the continued divorce at the very top of responsibility between

strategic planning and budget preparation which General Marshall had warned

against. The Joint Chiefs conceived their plans in terms of requirements for

men and materiel without considering the

[280]

JOINT ARMY PLANNING RELATIONSHIPS

* When the initially developed budget undergoes a subsequent

change resulting from decisions by higher authority, these changes are reflected

through a corresponding revision of the control program.

Source: FM 101-51, DA, 10 Oct 57, DA Planning & Programming

Manual, p.16.

[281]

available funds. The Secretary of Defense

continued to make decisions on budgets, particularly budget reductions, without

adequate knowledge of the impact these decisions might have on U.S. military capabilities.

He allocated funds in bulk to each of the three services which made further allocations

within their own departments in accordance with their own priorities. Joint operations

frequently suffered, notably when the Air Force could not provide the Army with

military air transport.

Another reason for

the disparity between Army plans and budgets was that its programs were rarely

completed in time to be incorporated into current budget requests. Since generally

the organizations or agencies responsible for developing programs also prepared

the Army's budget estimates, the pressing requirements of current operations

hampered program planning for the future. This handicap continued despite repeated

revisions of the Army Program System.

Beginning in 1954

the Army developed a different approach, finally designated in 1359 as the Army

Command Management System (ACMS). Under this system installation commanders

received budget guidance in the form of five-year projected estimates, based

on Army mid-range planning, which were revised annually with changes in Congressional

appropriations. These estimates, called "Control Programs," involved

five major areas: Troop, Materiel, Installations, Reserve Components, and Research

and Development. Using these estimates installation commanders were supposed

to prepare detailed requests for funds under twenty-one major functions covering

the Army's nontactical peacetime support activities. (Table 2) The ACMS

was intended to provide both cost and performance data for the amorphous budget

category, Operations and Maintenance, Army (O&MA). However, Mr. McNeil's

continued insistence on archaic obligation and expenditure data remained a major

obstacle. Another problem was the effort to develop a prototype Class I installation

automatic data processing system at Ft. Meade which would integrate supply,

personnel, and financial reporting. In this pioneering research project one

officer involved said the actual programming was "like dropping a ping-pong

ball into a box-full of mouse traps and ping-pong balls. If you've ever tried

it, you know that all hell breaks loose. We hit problems that were far more

complex than

[282]

TITLES AND CODE ZONE DESIGNATIONS OF

MAJOR ACTIVITIES UNDER THE ARMY MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE

| Major Activity |

Code Zone |

| Military Personnel, Army |

1000.0000-1990.0000 |

| Tactical Forces |

2000.0000-2090.0000 |

| Training Activities |

2100.0000-2190.0000 |

| Central Supply Activities |

2200.0000-2290.0000 |

| Major Overhaul and Maintenance

of Materiel |

2300.0000-2390.0000 |

| Medical Activities |

2400.0000-2490.0000 |

| Army-wide Activities |

2500.0000-2590.0000 |

| Army Reserve and ROTC |

2600.0000-2690.0000 |

| Joint Projects |

2700.0000-2790.0000 |

| Procurement of Equipment and Missiles,

Army |

4000.0000-4990.0000 |

| Research, Development, Test, and

Evaluation |

5000.0000-5990.0000 |

| Military Construction, Army |

6000.0000-0990.0000 |

| National Guard Personnel, Army |

7000.0000-7090.0000 |

| Operation and Maintenance, Army

National Guard |

7100.0000-7990.0000 |

| Reserve Personnel, Army |

8000.0000-8490.0000 |

| Military Construction, Army National

Guard |

8500.0000-8590.0000 |

| Military Construction, Army Reserve |

8600.0000-8690.0000 |

| Operation and Maintenance of Facilities |

9000.0000-9090.0000 |

| Promotion of Rifle Practice |

0500.0000-0590.0000 |

| Army Industrial Fund Activities |

3000.0000-3990.0000 |

| Other Operational Activities |

0800.0000-0990.0000 |

Source: AR 1-11, 17 Jan 58.

anyone ever dreamed. Every problem we

hit begat a host of new ones, chain-reaction style. And on anything like this,

you have to have all the kinks out." 14

The development of

functional budgets and programs was the principal effort in the 1950s to improve

the Army's financial management. During this period continued criticism from

agencies outside the Department of Defense focused on other problems that made

effective control over the Army's finances difficult. The Flanders Committee

in 1953 investigated the efforts of the military services to carry out the fiscal

reforms

[283]

called for in the

National Security Act amendments of 1949. It complained of the lack of progress

in setting up uniform budget and accounting systems, revolving operating funds,

and the development of adequate financial statistical reports.15

The Davies Committee

report in December 1953 recommended integrating the Army's financial management

systems with its formal command organization. The new functional budget and

programing system ought to reflect the actual cost of Army operations, it said,

on the basis of the "missions" the Army had to perform rather than

the functional means of accomplishing them. The committee also criticized the

existence within the Army of more than thirty separate accounting systems which

could not be correlated rationally. There should be a single, uniform system

of accounting that would adequately measure the "costs of performance."

That meant the adoption of modern, "accrual" cost-accounting systems

and double-entry bookkeeping at all levels of the Army.16

President Eisenhower's

first Secretary of Defense, Charles E. Wilson, appointed a special Advisory

Committee on Fiscal Organization and Procedures within the Department of Defense,

known as the Cooper Committee, which recommended replacing the traditional "obligation-allotment"

form of accounting with modern "cost-of-performance" budgets as a

more rational means of controlling defense costs. One committee member, Wilfred

McNeil, disagreed. As Comptroller of the Department of Defense he was successful

in preventing the adoption of this recommendation.17

The Second Hoover

Commission on the Organization of the. Executive Branch of the Government in

1955 again criticized military budgeting and accounting systems as archaic and

recommended that Congress require budgets and accounting systems based on a

cost-of-performance or "accrual" basis. Congress passed such a law

in 1956 (Public Law 863, 89th Congress,

[284]

1 August 1956) , but

because of Mr. McNeil's opposition it remained largely a dead letter.18

Certainly one of the

original reasons for the whole movement toward unification in the armed forces

was the belief that separate service supply organizations were duplicating and

wasteful. General Somervell's Army Service Forces was the principal champion

of the idea of a completely unified supply and service system for the Army,

Navy, and Air Force, and it was largely because of the ASF influence that the

War Department, in the first phases of the unification hearings, supported the

idea of a unified supply organization. General Lutes, wartime ASF Director of

Operations and in 1947 Director of Supply, Services, and Procurement on the

General Staff, had a study prepared in January 1947 that declared:

Procurement, supply

and service operations will never be as efficient on the basis of voluntary

cooperation as they can be if integration is required . . . . There are large

savings to be had in unified service, supply and procurement for the Armed Forces.

These are not only savings in money, but also savings in the resources that

are scarce in time of war-men, material, facilities, time.19

By 1947, however,

Lutes represented a voice crying in the wilderness as the Army in general backed

away from the concept of a fourth military department handling supplies and

services, even as it fragmented its own functions in this area by restoring

the technical services to their former power and authority. The Navy had consolidated

its own common supply functions in the 1890s under the Bureau of Supplies and

Accounts but championed "voluntary cooperation" among the services

in supply as well as in other fields. The fledgling independent Air Force, irked

with its dependency on the Army supply system for many common supplies and services,

sought to establish its own independent supply system. The Eisenhower-Spaatz

agreement of 15 September 1947 provided that the Army and Air Force would use

each other's services and facilities

[285]

"where economy

consistent with operational efficiency will result." According to some

critics the Air Force interpreted "operational efficiency" as requiring

a completely separate supply system regardless of duplication and overlap.

The Army position

by the early 1950s had changed similarly. A single supply service, the Assistant

Secretary of the Army asserted in 1951, would mean the military would lose "command

control of supply and thus direction of military operations." The necessity

for unity of command over military operations became, in all three services,

the basis of opposition to any revival of the Somervell-Lutes proposals 20

The principal champions

of integrated supply systems were to be found in Congress and the business world,

not in the military services. Under constant prodding from the outsideby Congress

and the two Hoover Commissions-the movement toward increased co-ordination and

integration of service supply systems gained momentum between 1947 and 1960.

The impact on the Army's technical services was considerable.

The National Security

Act of 1947 gave the Secretary of Defense an ill-defined authority to eliminate

duplication and overlap among the services in the supply area and created a

co-ordinating authority in the Munitions Board which, along with other functions,

was to work toward these ends.21

The accomplishments of the Munitions Board along this line were not great, at

least in part because some regarded it as the forerunner of a. single defense

supply service, but it did initiate some important programs that laid the basis

for future developments, and it conducted many studies. Its main work was in

the area of procurement where it originated what was later to be known as the

Coordinated Procurement Program under which one service acted as purchasing

agent for certain categories of items for the others. This arrangement provided

benefits of consolidated purchasing such as lower prices and fewer purchasing

personnel. It did not provide effective control over inventories nor eliminate

the duplication created by the existence of

[286]

different storage

and distribution systems, including the seven different systems of the Army

technical services .22

Meanwhile, in 1948,

Congress passed the Armed Forces Procurement Act, requiring the development

of uniform procurement procedures for all the military departments. The main

purpose of the act was to free the military services from the prewar requirement

that all procurement in peacetime be by open competitive bidding, a requirement

that was impractical in many cases. The act spelled out specific requirements

that must be met to justify negotiated contracts. To carry out the purposes

of the act a special committee drafted a set of Armed Services Procurement Regulations

(ASPR's) that became, with their periodic revisions, the bible of procurement

procedures for the Department of Defense.

Not unexpectedly performance

did not live up to ASPR's promise. The Second Hoover Commission Task Force on

Military Procurement in 1955 stated the ASPR lacked adequate coverage. Consequently

it had spawned a mass of subordinate individual service regulations. There was

also, it said, a wide gap between the ASPR and actual procurement procedures

at the working level in the field which frustrated contractors. The Task Force

recommended rewriting the ASPR to take care of these deficiencies.23

Other important steps

in the 1947-50 period included the establishment of the Military Sea Transportation

Service (MSTS) and the Military Air Transport Service (MATS) with responsibilities

for handling ocean surface transportation and air transportation, respectively,

for the three services. The

[287]

activation of MSTS

removed the Army Transportation Corps from the field of shipping in which it

had been engaged since the Spanish-American War. On the other hand, insistence

on unity of command over operations frustrated efforts to create an integrated

military land transportation service in the United States until 1956.24

The First Hoover Commission

report in 1949 did not, as the second report was to do, recommend a radical

alteration of the DOD logistics structure. However, it did recommend that ".

. . the National Security Act of 1947 be specifically amended so as to strengthen

the authority of the Secretary of Defense in order that he may integrate the

organization and procedures of the various phases of supply in the constituent

departments of the National Military Establishment."25

The provisions of the National Security Act amendments in 1949 concerning the

establishment of performance budgets, stock and industrial funds, and cost-of-performance

accounting made greater integration of defense activities possible. The stock

fund principle introduced in the Army as a result-the Navy had long had one

and the Air Force was never to use stock funding to any considerable degree-greatly

facilitated cross-servicing and provided a mechanism for the later operation

of single managers.

Another outgrowth

of the Hoover Commission report was the Federal Property and Administrative

Services Act of 1949 creating the General Services Administration (GSA) with

government-wide responsibility for central purchasing and management of common

supplies and services. However, it provided that the Secretary of Defense might

use his discretion in exempting the military services from purchasing common

supplies through GSA. For the most part successive Secretaries of Defense did

so, but under a policy that provided for maximum use of GSA facilities where

it would promote efficiency and economy. As the situation developed, GSA assumed

responsibility for providing general office supplies and equipment for the armed

services and for planning, constructing, managing,

[288]

and operating buildings

occupied by the military establishment in the United States. Beyond this the

extent to which each service used GSA as a purchasing agent for common supplies

was a decision to be made by that service 26

Indeed defense policy quite specifically stipulated that there should be separate

service supply establishments. The philosophy under which successive Secretaries

of Defense proceeded, at least until 1955, was set forth in 1949 by Secretary

Louis A. Johnson: "Each of the services is responsible for the logistic

support of its own forces except when logistic support is otherwise provided

for by agreement or assignments as common servicing, joint servicing, or cross

servicing at force, command, department or Department of Defense level."

27

Congress, demanding

greater progress in integrating supply management, became disenchanted with

the Munitions Board. In the Defense Cataloging and Standardization Act of 1952

it transferred the board's functions to a new Defense Supply Management Agency.

The Eisenhower Reorganization Plan No. 6 abolished both this agency and the

Munitions Board, replacing them with a single executive, an Assistant Secretary

of Defense for Supply and Logistics.28

The Korean War led

to several investigations by Congress of military supply management which threatened

to impose a common supply service on the military services from the outside.

The investigation begun in 1951 by the House Committee on Expenditures in the

Executive Departments, known as the Bonner Committee, was the most important.

It charged that, contrary to the Eisenhower-Spaatz agreement, the Air Force

in developing its own supply system had included items commonly used by both

the Army and Air Force. It criticized the lack of co-ordinated supply management

among the Army's technical services, citing conspicuous examples of waste in

competitive buying, overstocking, and duplication in the use of personnel, space,

and facilities. It accused the services of giving only lip service to the principles

of integrated supply manage-

[289]

ment and quietly agreeing

among themselves to emphasize separatism rather than integration.

The Bonner Committee

concluded that supply management within the Department of Defense and the services

lacked adequate centralized control. As a result of its recommendations Congress

adopted the O'Mahoney amendment to the Defense Appropriations Act of 1953 prohibiting

the "obligation of any funds for procurement, production, warehousing,

distribution of supplies or equipment or related supply management functions,

except in accordance with regulations issued by the Secretary of Defense."

Complying with this provision, Secretary of Defense Lovett on 17 November 1951

issued DOD Directive 4000.8, Basic Regulations for the Military Supply System,

ordering the Air Force to abide by the principles of the Eisenhower-Spaatz agreement,

among other things. It listed eleven general principles governing the management

of defense supply and service activities, including cross-servicing, single

procurement, cataloging and standardization, conservation, surplus disposal,

transportation, and traffic management. It expressly prohibited the addition

of new independent or expanded supply functions involving standard, common-use

items without the approval of the Secretary of Defense. One provision required

the services to establish "one single supply and inventory control point

for each specified category of items." By 1960 there were twenty-four such

"National Inventory Control Points" in the Army. 29

The Bonner Committee

became the Riehlman Committee in January 1958 with the change in Congressional

control to the Republican party and continued its investigations. Later that

year it reported that the services were still too slow in improving their management

of supply, asserting that one major reason was that each service was "dedicated

to its own systems and procedures." The new Assistant Secretary of Defense

for Supply and Logistics, Charles E. Thomas, and his successor, Thomas P. Pike,

both disagreed with these findings and opposed further efforts to integrate

common supply activities as a fragmented approach which did not recognize "the

[290]

basic fact that each military supply system

is maintained solely to provide supplies as needed by the tactical forces that

they were called upon to support." 30

While the Riehlman

Committee produced no tangible results, the Commission on Organization of the

Executive Branch of the Government created by Congress on 10 July 1953 and known

as the Second Hoover Commission did. Its Task Force on the Business Organization

of the Department of Defense charged the Department of Defense and the military

services with continued waste, overlapping, and duplication of effort in nearly

all aspects of supply management. Co-ordination was piecemeal and fragmentary.

Substantial economies and greater efficiency could only be achieved by creating

within the Department of Defense a civilian defense supply and service administration,

which would perform common supply and service functions all over the world.31

The military services

opposed a civilian common supply agency even more than a military one. They

charged it would be less responsive to military requirements and so jeopardize

the success of military operations. An Army staff study, The Fourth Service

of Supply and Alternatives, prepared in the Business and Industrial Management

Office of the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics in September

1955 followed this line of argument. The Hoover Commission and its Task Force

on the Business Organization of the Defense Department, it said, did not give

adequate attention to the military aspects of military supply management. They

emphasized peacetime operations. The Task Force's assertions concerning the

inefficiency of military supply management were based on "unsupported assumptions."

A civilian agency,

according to DCSLOG, would produce further duplication of personnel and functions,

increase competition for scarce professional and technical skills, and make

it difficult for the Army to train its own military logistical

[291]

managers and service

troops. Recruiting civilian supply personnel in wartime or for overseas services

was also undesirable. In conclusion the Task Force said that a civilian "Fourth

Service of Supply" would impair the Army's ability to carry out its assigned

military missions.

It admitted the existence

of deficiencies in supply management, but it said the best way to correct them

was to improve management practices within the existing organizational framework

rather than create a separate agency. Among the alternatives it suggested were

to accelerate adoption of uniform inventory management practices, the standardization

of supply documents, and some form of integrated management for subsistence

and for medical supplies.32

Congress did not appear

as impressed with the argument of military necessity as it was with the Hoover

Commission's indictment of waste and inefficiency in the military services.

To avoid having Congress take the matter away from the services entirely, the

Department of Defense did an about face. A prime mover in bringing about a more

favorable attitude toward greater integration in supply management was the new

Deputy Assistant Secretary for Supply and Logistics, Robert C. Lanphier, Jr.,

a Midwestern electric and utility company executive. Beginning in late 1954

a task force in his office spent several months exploring how best to achieve

a maximum degree of integration with a minimum of disruption to the existing

service organizations. The solution proposed and approved by the Secretary of

Defense was to appoint "Single Managers" for a selected group of common

supply and service activities.

The single manager

concept was the most significant advance toward integrated supply management

within the Department of Defense or the armed services since the end of World

War II. Basically it was an expansion of the Single Service Procurement Program

to provide more effective control over inventories at one end of the supply

cycle and greater control over wholesale distribution at the other. Like the

Single Service Procurement Program it superimposed a new organiza-

[292]

tional pattern on

the existing one instead of creating a new organization.

When the concept was

presented to the Secretary of Defense and the services the Navy, adhering to

its traditional opposition to integration in any form, opposed it on principle.

A new Deputy Secretary of Defense for Supply and Logistics, Reuben B. Robertson,

Jr., a paper company executive who had served as vice chairman of the Second

Hoover Commission's Committee on the Business Organization of the Department

of Defense, overruled the Navy's objections and approved a directive outlining

the procedures and principles to be followed in setting up single managerships.

Under this directive

the Secretary of Defense would formally appoint one of the three service secretaries

as single manager for a selected group of commodities or common service activities,

and he, in turn, would select an executive director to operate the program.

Single managers in the Army were established within the existing technical service

organizations. The Secretary of the Army designated a major general as executive

director who served under the chief of the technical service responsible for

the particular type of commodity or service involved. The Single Managers for

Subsistence and for Clothing and Textiles operated under the Quartermaster General,

while the Single Manager for Military Traffic Management was under the Chief

of Transportation.

The responsibility

of the single managers for determining requirements involved common cataloging

and standardization as well as inventory control. They operated under a stock

or consumer revolving fund, buying what they needed, selling to the military

departments and consumers, and using the funds paid to replenish their stocks.

This eliminated the expense and delay in calling for open bids each time supplies

were requested. Through their control over wholesale storage they were able

to direct distribution to consumers from the nearest depot, regardless of the

service operating it, in such a manner as to avoid the needless and expensive

cross-hauling involved when each service maintained its own completely separate

distribution systems.

Under this system

the technical services preserved their organizational integrity. The single

managers operated through

[293]

normal command channels,

reporting to the Secretary of the Army through the chiefs of the technical services

and the Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics, who was assigned Army staff responsibility

for the single manager programs. The impact of losing control over their inventories

was minimal because this was a function the technical services had never chosen

to exercise effectively. They continued to calculate their own requirements,

and they retained their own wholesale and retail distribution systems. The chief

difference was that they operated their wholesale depots now as agents of the

single managers rather than the several technical services. In sum, the single

manager concept balanced demands for greater integration of supply management

with the military services' insistence that effective military operations required

each service to maintain its own independent supply system.

One factor which delayed

expansion of the single manager system was the requirement for common cataloging,

standardization, accurate inventories, and the necessity to set up cost-ofperformance

accounting systems for each single manager stock fund.33

According to Mr. Lanphier,

in late 1955, the most appropriate categories for initial single manager assignments

were subsistence and clothing and textiles, both of which were assigned to the

Army's Quartermaster Corps, and petroleum and medical and dental supplies, both

of which were assigned to the Navy's Bureau of Supplies and Accounts. These

were areas of largely common-use items, where common cataloging was relatively

complete, where some defense-wide co-ordination existed, and where much of the

wasteful duplication of inventories and cross-hauling existed. The Military

Subsistence Supply Agency was the first to be inaugurated on 4 November 1955,

followed in the next year by the three others. The coordination of transportation

services was also far advanced. Creating single managerships out of the existing

Military Air Transport Service and the Military Sea Transportation Service was

simply a change in designation. The single manager for land traffic management,

the Military Traffic Management

[294]

Agency (MTMA), was

a new agency and assigned to the Transportation Corps. This function had gradually

developed over a decade against considerable Air Force opposition.34

Assignments in 1959

of single managers for general supplies to the Army's Quartermaster Corps as

the Military General Supply Agency (MGSA), for industrial supplies to the Navy's

Bureau of Supplies and Accounts as the Military Industrial Supply Agency (MISA)

, for construction supplies to the Army's Corps of Engineers as the Military

Construction Supply Agency (MCSA), and for automotive supplies to the Ordnance

Department as the Military Automotive Supply Agency (MASA) were the result of

studies undertaken by the Armed Forces Supply Support Center mentioned below.

They required much more work in common cataloging, standardization, accurate

inventorying, and the installation of cost-of-performance accounting. Further

studies by the Armed Forces Supply Support Center in 1960 envisaged an additional

single managership for electrical and electronic supplies.35

The impact of the

single manager system within the Army was greatest on the Quartermaster Corps,

which was, by 1960, responsible for three of them. Three of its four identifiable

procurement systems were single managerships, and the Quartermaster General

asserted that nearly all his supply and procurement personnel were involved

either with the single managerships or other efforts to integrate defense supply

management.36

Another program designed

to eliminate duplication and prevent waste by permitting the transfer of surpluses

among the services was the Interservice Supply Support Program begun in 1955.

It consisted of six area co-ordination groups under a joint council of the services

and governed thirty-three commodity co-ordination groups.37

[295]

Finally, in June 1958,

the Department of Defense created the Armed Forces Supply Support Center (AFSSC)

to administer the common cataloging, standardization, and Interservice Supply

Support programs, the latter redesignated as the Defense Utilization Program.

It was also to study military supply activities continually and recommend improvements

in their management. From such analyses came proposals leading to the creation

of the four additional single managerships in 1959 and 1960, referred to above.38

While all these efforts

were being made within the Department of Defense to improve supply operations,

Congress continued its criticisms of waste, duplication, and overlap and of

the slow progress being made to eliminate them. In 1958 nearly a dozen different

bills were introduced into Congress to establish a fourth service of supply.

The outcome was the addition of the McCormack-Curtis amendment to the Defense

Reorganization Act of 1958 which granted the Secretary of Defense explicit authority

to consolidate or integrate the supply and service functions of the three services,

subject to a Congressional veto where this involved legislative changes. The

amendment stated:

Whenever the Secretary

of Defense determines it will be advantageous to the Government in terms of

effectiveness, economy, or efficiency, he shall provide for the carrying out

of any supply or service activity common to more than one military department

by a single agency or such other organizational entities as he deems appropriate.39

Congress continued

to scrutinize defense supply management and to demand further integration.

At the end of the

fifties the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff possessed much

greater authority and control over the three military services than Congress

had provided for or intended in the National Security Act of 1947. The cold

war, the revolution in technology, mounting defense costs, and pressure from

industry and Congress were responsible for this increase in power. It was most

apparent in four

[296]

areas-strategic planning

and the direction of military operations, financial management, logistics, and

research and development.

The first substantial

increase in the authority of the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of

Staff came with the passage of the National Security Act amendments of 1949.

The Secretary of Defense's increased authority over defense budgets, calling

for their reorganization along functional lines, was perhaps the most significant

change. At the same time the Secretary's civilian staff and the joint staff

serving the joint Chiefs of Staff were also increased in size.

The Eisenhower Reorganization

Plan No. 6 of 1958 brought about further increases in the authority of the Secretary

of Defense and the Joint Chiefs. The various functional boards set up under

the 1947 act, stymied by interservice rivalry, were replaced by a series of

functional assistant secretaries with authority to act on behalf of the Secretary.

The civilian staffs of the service secretaries were also reorganized on functional

lines, reflecting the changes within the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

The joint staff was again increased in size and the chairman of the joint Chiefs

given greater authority over the joint staff's operations.

Congressional prodding

and Soviet technological achievements led to the Defense Reorganization Act

of 1958 which centralized authority over the services in the Secretary of Defense

and his office even further. The chain of command over military operations was

changed to run from the President and Secretary of Defense through the joint

Chiefs rather than through the service secretaries who had acted as executive

agents since 1953. The JCS, its staff doubled to four hundred, was completely

reorganized along conventional military staff lines, replacing the system of

JCS committees, most of which were abolished. The authority of the chairman

of the joint Chiefs of Staff over the joint staff was increased, and at the

request of President Eisenhower he was given a vote in JCS decisions previously

denied him by Congress.

Authority over the

research and development of new weapons and weapons systems was centralized

under a new Director of Defense Research and Engineering. The McCormack-Curtis

[297]

amendment also gave the Secretary of Defense

greater discretional authority to integrate service supply activities.40

This increasingly

centralized control by the Secretary and the Department of Defense obviously

diminished the role of the services. They had become support commands, responsible

for training, administration, and logistical support of military operations,

limited further by the authority of the new Director of Defense Research and

Engineering over the development of new weapons.

The Department of

the Army became responsible largely for functions performed by the Army Ground

Forces and the Army Service Forces during World War II. There was continual

discussion of whether the Secretary of the Army should act as an independent

spokesman for the Army or as an executive vice president for the Secretary of

Defense. The answer depended somewhat on the personalities involved and their

length of service. The long tenure of Mr. McNeil as Defense Comptroller and

Secretary of the Army Wilber M. Brucker undoubtedly increased their personal

influence, but generally the tour of duty for top-level civilian administrators

was relatively brief as it had been in the past. Other things being equal, under

a strong Secretary of Defense the service secretaries were more likely to act

as his executive agents than under a weak one. 41

[298]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the

Table of Contents