Chapter VIII:

The McNamara Revolution

One of the major issues of the

1960 Presidential campaign was the alleged inadequacy of the Eisenhower

administration's direction and management of the nation's security. Two

of the principal critics were retired Army Chief of Staff General

Maxwell D. Taylor and the former Army Chief of Research and Development

Lt. Gen. James M. Gavin. The Subcommittee on National Policy Machinery

of the Senate's Committee on Government Operations, under Senator Henry

M. Jackson of Washington, began a series of hearings and investigations

in January 1960 which also concentrated on the inadequacy of this

country's national security organization. Senator John F. Kennedy, when

running for President, appointed Senator Stuart E. Symington of

Missouri, a former Secretary of the Air Force under President Truman,

chairman of an advisory committee to investigate the organization and

operations of the Department of Defense. Finally two RAND Corporation

officials, Charles J. Hitch and Roland N. McKean, criticized the

financial management of the Department of Defense in The Economics

of Defense in the Nuclear Age.

General Gavin charged that the

roles of the joint Chiefs as heads of separate military services were

incompatible with their functions as the nation's top military planners

because they could not in practice divorce themselves from the

particular interests of their individual services. There were

"interminable delays" in reaching decisions caused by

disagreement and deadlock among the services. He suggested abolishing

the joint Chiefs of Staff and substituting a Senior Military Advisory

Group to the Secretary of Defense. Its members would be senior officers

who had just completed a tour of duty as their service's chief of staff,

and a functional joint staff would support them.1

[299]

General Taylor had become the

principal military spokesman of the Marshall tradition of tight

executive control over the armed services before and after his

retirement as Chief of Staff of the Army. In The Uncertain Trumpet, he,

like General Gavin, was critical of current military strategy because it

neglected the Army in favor of the massive deterrent of the Strategic

Air Command. Concentration on total nuclear war similarly neglected the

requirements of conventional and limited warfare, the principal type of

conflict that had developed during the cold war.

Like General Gavin, Taylor also

criticized the procedures by which the joint Chiefs of Staff reached

their decisions. Repeating General Marshall's dictum, he told the

Jackson Committee that "you cannot fight wars by committee." A

single armed services chief of staff should run the Secretary of

Defense's "command post" for him, assisted by an advisory

council. In summary effective control over operations required more

efficient planning as well as a more efficient planning organization.

The current role of the Defense

Department Comptroller disturbed General Taylor. Given the fact that the

joint Chiefs of Staff were often in deadlocked disagreement, he asserted

that "strategy has become a more or less incidental by-product of

the administrative processes of the defense budget." To avoid this

situation he would restructure defense budgets on the basis of the

strategic missions to be performed rather than on the resources or

functions required to perform them. What was needed was a strategy of

"flexible response" capable of meeting all levels of conflict

from "cold" through "limited" to "total"

war; "atomic" deterrent forces based on intercontinental

missiles rather-than manned bombers; "counterattrition forces"

capable of fighting "brush fire wars;" guerrilla and other

"limited" conflicts; mobile reserve forces, including

mobilization stockpiles; air lift and sea lift forces; antisubmarine

warfare forces; continental air defense based on the development of

antimissile missiles; plus whatever resources were required to support

general mobilization and civil defense programs. The three military

services would be reorganized similarly as operational commands while

the three service departments would be organized to mobilize, train, and

support

[300]

them. In this manner American

military commitments could be balanced effectively with the resources

required to fulfill them, another objective which General Marshall had

posited at the end of World War II.2

Outside the military services a

special Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee of the Senate Armed

Services Committee under the chairmanship of Senator Lyndon B. Johnson,

Democrat of Texas, in 1957 began a continuing series of inquiries into

satellite and missile programs, into the role of the Bureau of the

Budget in formulating and executing defense budgets, and into other

major issues.

Senator Jackson's Subcommittee

on National Policy Machinery investigated "whether our Government

is now properly organized to meet successfully the challenge of the cold

war." 3

Former Secretary of Defense

Robert A. Lovett, a leading civilian disciple of General Marshall, was

the first witness to testify before this committee. Echoing his

predecessor, he said bluntly that the "committee system" under

which the Department of Defense and, indeed, the entire federal

government operated traditionally was the principal obstacle to

effective decision-making. He admitted that the committee system had

developed out of the federal form of government as part of "a

series of checks and balances" to prevent any one group within the

government from becoming too powerful.

The often forgotten fact is that

our form of government, and its machinery, has had built into it a

series of clashes of group needs...This device of inviting argument

between conflicting interests-which we can call the "foulup

factor" in our equation of performance-was obviously the result of

a deliberate decision to give up the doubtful efficiency of a

dictatorship in return for a method of protection of individual freedom,

rights, privileges, and immunities.

Mr. Lovett feared that within

the executive branch alone there was an observable trend to expand the

committee system

[301]

to the point where mere

curiosity on the part of someone or some agency and not a "need to

know" can be used as a ticket of admission to the merry-go-round of

"concurrences." This doctrine, unless carefully and boldly

policed, can become so fertile as spawner of committees as to blanket

the whole executive branch with an embalmed atmosphere . . . . The

derogation of the authority of the individual in government, and the

exaltation of the anonymous mass, has resulted in a noticeable lack of

decisiveness. Committees cannot effectively replace the decision-making

power of the individual who takes the oath of office; nor can committees

provide the essential qualities of leadership.4

Thus did Mr. Lovett compare the

Marshall tradition concept of tight executive control with the

traditional procedures of completed staff actions.

Senator Stuart Symington

represented Air Force critics of the JCS committee system. As chairman

of a task force on defense organization and management appointed by

Senator Kennedy during his 1960 campaign for President, Symington

heavily weighted his committee with Air Force spokesmen. One was Thomas

K. Finletter, the first Secretary of the Air Force. Another was former

Assistant Secretary and later Under Secretary of the Air Force Roswell

L. Gilpatric.

Not surprising, the criticisms

and recommendations made by the Symington Committee reflected policies

advanced by the Air Staff in 1959 in its "Black Book on Defense

Reorganization" favoring "total unification."

Interservice rivalry, the committee said, prevented the JCS from

functioning effectively. To eliminate this rivalry it recommended

abolishing the joint Chiefs of Staff in favor of a single armed forces

Chief of Staff, called the "Chairman of the Joint Staff," who

would be chief military adviser to the Secretary of Defense and the

President and direct the activities of the joint staff. He would also

preside over a Military Advisory Council composed of those senior

officers who had just completed tours of duty as chiefs of staff.

Divorced from their services they would no longer feel required to place

service interests above everything else.

Second, the Symington Committee

proposed to abolish the three "separately administered"

services and reorganize them as "organic units within a single

Department of Defense." The Secretary of Defense would be assisted

by two Under Secretaries, one for Weapons Systems and another for

Administration. The former would be responsible for all logistical

support

[302]

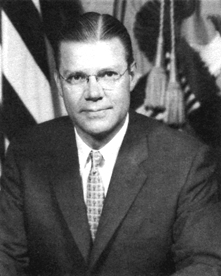

SECRETARY McNAMARA

activities, including research

and development, production, procurement, and military construction and

installations. The latter would be responsible primarily for personnel

and financial management. A series of functional directorates similar to

the existing Assistant Secretaries of Defense would act as the

department's staff.

Finally, to integrate the

services completely the committee recommended adopting uniform

recruitment policies, uniform pay scales, unified direction of all

service schools, and a more flexible policy of transferring personnel

among the services. The military services would retain their individual

chiefs of staff who would have direct access to the Secretary of

Defense. The services would also retain such vestiges of their former

separate identities as their distinctive uniforms.5

Spokesmen for the Army's

Marshall tradition and the Air Force were the major critics of the

Eisenhower defense policies and organization. Representatives of the

Navy, which remained the principal supporter of the JCS committee

system, were conspicuous by their absence. Supporting the critics was

the

[303]

Mr. VANCE

observable trend of the previous

decade in the direction of greater authority and control over the

services by the Secretary of Defense. As one student of the defense

organization put it: "Gradually, and with a finesse which demands

respect, the services are being dismembered and disembowelled, so that

the question of their utility is decided continually in decrements.

Since we cannot reasonably expect to turn the clock back, the only

relevant question is whether the process is too fast or too slow."

6

The trend toward centralized

authority in the Secretary of Defense seemed likely to continue, but

future developments were partly contingent on the man President Kennedy

selected as his Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara. McNamara was a

highly successful industrial manager, a "comptroller" in the

broadest sense of that much-abused and misunderstood term. Most of the

reforms he instituted as Secretary of Defense and the techniques he

employed were ones which management experts since the days of General

Somervell's Control Division had repeatedly recommended. What was unique

was the rapidity with which he absorbed information and made decisions.

What had disturbed him most at the outset was the long time it took to

get decisions out of the Department of

[304]

Mr. HITCH

Defense. In the General Marshall

tradition he placed the blame for delay on the committee system with its

endless bargaining and compromises. He intended to replace committees

where possible by asserting greater executive authority, responsibility,

and control over the department and its operations. As he said,

"The individual in the position of responsibility must make the

decision and take the responsibility for it." 7

Secretary McNamara was surprised

to find that there was no management engineering agency within his

office responsible for reviewing organization and procedures. He

promptly assigned this function to the department's new General Counsel,

Cyrus R. Vance, a veteran of the Johnson Defense Preparedness

Subcommittee. Another Johnson subcommittee veteran, Solis Horwitz,

became Director of the Office of Organizational and Management Planning

under Mr. Vance. This agency was responsible for directing or

supervising studies requested by Secretary McNamara in its assigned area

and for monitoring major organizational changes in the Department of

Defense stemming from such projects.

One study led to regrouping the

functions of the Assistant

[305]

Secretaries of Defense. The two

Assistant Secretaries for Manpower, Personnel, and Reserve and for

Health and Medical services were combined under one Assistant Secretary

for Manpower. The Assistant Secretaries for Supply and Logistics and for

Property and Installations were also combined under one Assistant

Secretary for Installations and Logistics. An Assistant Secretary for

Civil Defense was added because this function had been transferred to

the Defense Department. Other studies resulted in abolition of more than

five hundred superannuated departmental committees and in a major

reorganization of the Air Force's field establishment into a research

and development or Systems Command and a Logistics Command.8

Secretary McNamara's first major

reform was to revise the Defense Department's budget to reflect the

military missions for which it was responsible. The person most directly

responsible for this project was the new Defense Comptroller, Charles J.

Hitch. The Office of the Comptroller in the Army for several years had

advocated such a budget. When McNamara became Secretary of Defense the

Army's Chief of Staff was General George H. Decker, a former

Comptroller, who sought to develop some means of presenting the Army's

costs of operation in mission terms. In the fall of 1960 shortly after

he became Chief of Staff, Decker had initiated additional investigations

of this concept.9

Mr. Hitch believed that the

combination of functional budget categories and the rigid budget

reductions of the Eisenhower administration had created unmanageable

problems, with each service favoring its own projects at the expense of

joint ones, concentrating on new weapons systems at the expense of

conventional ones, and neglecting maintenance.

The Army's own modernization

program emphasized the development of missiles and Army aviation at the

expense of conventional weapons and equipment, Mr. Hitch charged. In

[306]

an era of financial austerity

the Army's major overhead operating costs, the operations and

maintenance program, suffered most. More and more equipment was useless

for lack of spare parts. Deferred maintenance seriously impaired the

Army's combat readiness. Local commanders often had to transfer

operations and maintenance funds intended for repairs and utilities for

more urgent missions, an illegal transaction made possible by the thin

dividing line that existed in practice between procurement activities

and overhead operations.10

Another major weakness of the

existing budget was the failure to relate functional appropriations to

major military missions or objectives. Mr. Hitch proposed a series of

nine "Program Packages" designed to solve this problem. (Table

3)

MAJOR PROGRAMS, TOTAL

OBLIGATIONAL AUTHORITY

(IN BILLIONS OF DOLLARS)

| Major

Programs |

FY

1961

Actual 2 |

FY

1962

Original |

FY

1962

Actual |

FY

1963

Estimated |

| Strategic

Retaliatory Forces |

|

7.6 |

9.1 |

8.5 |

| Continental

Air and Missile Defense Forces |

|

2.2 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

| General

Purpose Forces |

|

14.5 |

17.5 |

18.1 |

| Airlift/Sealift

Forces |

|

.9 |

12 |

1.4 |

| Reserve

and Guard Forces |

|

1.7 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

| Research

and Development |

|

3.9 |

4.3 |

5.5 |

| General

Support |

|

12.3 |

12.7 |

13.7 |

| Civil

Defense |

|

|

.3 |

.2 |

| Military

Assistance |

|

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

| Total

Obligational Authority |

46.1 |

44.9 |

51.0 |

52.8 |

-

- 1 Total obligational authority represents

the total financial requirements for the program approved for initiation

in a given fiscal year, regardless of the year in which the funds were authorized

or appropriated.

- 2 Breakdown not available for fiscal

year 1961.

-

- Source: Annual Report of the Department

of Defense, FY 1962, p. 367.

- [307]

- Only three of the new categories

referred to major military missions: strategic retaliatory forces, continental

air and missile defense forces, and general purpose forces for conventional

or limited war. Four categories, air lift and sea lift forces, research

and development, general support, and reserve forces were supporting activities.

Military assistance and civil defense, the latter soon replaced as a separate

category by retired pay, were separate categories for political reasons

as much as anything else because Congress insisted on treating these areas

separately from regular defense appropriations.11

-

- Congress did not accept these program

packages as a substitute for the service-oriented, functional appropriations

structure developed in the previous decade. As a consequence, Mr. Hitch

and the services with the aid of computers developed a means, known as a

torque converter, of translating program packages into appropriations categories

and vice versa, both for the current fiscal year and projected several years

into the future.

-

- Applying appropriations categories

to major military missions or to the research and development of major new

weapons systems was not too difficult. The problem was how to apportion

overhead operating costs like operations and maintenance among the major

missions and similarly to break down the general support package into standard

appropriations.12

-

- Since the major purposes of Mr.

Hitch's reforms were to enable Congress, the President, and the Secretary

of Defense to assert greater control over defense budgets and operations

and to balance military requirements with the resources available to carry

them out, much depended on the accuracy and uni-

- [308]

- formity of the statistical information

contained in budget requests. If inaccurate information were fed into computers,

the answers would be inaccurate. The lack of reliable cost data, particularly

for the Army's operations and maintenance program with which the department

and the Army had been struggling for more than a decade, remained a major

unsolved problem complicated by the continuing shortage of funds available

for this category of appropriations.13

-

- The analysis of resource requirements

and their allocation among competing military programs on a rational basis

was the responsibility of a new Office of Programming within the Department

of Defense Comptroller's Office under Hugh McCullough, a veteran with twenty

years' experience in military financial management including the research

and development of the Navy's Polaris missile system. Within this new office

a Systems Planning Directorate developed means by which to measure and translate

into financial terms the mat6riel, manpower, and other resources required

by the military services, a function currently known as force planning analysis.

-

- The most difficult assignment was

that of the Weapons Systems Analysis Directorate under one of Secretary

McNamara's famous "whiz kids," Dr. Alain C. Enthoven, a young

RAND Corporation alumnus. The failure to relate appropriations to new weapons

systems from their conception to their operational deployment and ultimate

obsolescence was, Hitch asserted, another great weakness of the existing

budget structure. What was needed, and what Dr. Enthoven's office attempted

to supply, was a rational means of estimating the costs of new weapons systems,

including not only the costs of research and development and of procurement

and production but their annual operating costs. Military officers neglected

the latter in their estimates because they were not accountable for these

costs. In evaluating alternative weapons systems and strategies Enthoven

and his staff employed cost-effectiveness analysis developed by economists

and systems analysis developed by operations research analysts. Their evaluation

included analysis of the objectives of competing strategies and

- [309]

- their often unstated underlying

basic assumptions. It sought wherever possible to substitute rational judgment

for guesswork in reaching decisions. As Mr. Hitch said:

-

- In no case . . . is systems analysis

a substitute for sound and experienced military judgment. It is simply a

method to get before the decision-maker the relevant data, organized in

a way most useful to him . . . . What we are seeking to achieve through

systems analysis is to minimize the areas where unsupported judgment must

govern in the decision-making process.14

-

- Cost effectiveness and systems analysis

introduced the jargon of statistics and computer technology into military

planning. When "the standard economic model of efficient allocation"

employed in cost effectiveness studies was defined as "the maximization

of a quasi-concave ordinal function of variables constrained to lie within

a convex region," a communications gap opened between the systems analysts

and those combat veteran officers unfamiliar with the language. Within the

Army it was several years before similar agencies for Force Planning Analysis

(21 February 1966) and Weapons Systems Analysis (20 February 1967) were

established on the Army staff to match the organization in the Department

of Defense Comptroller's Office. By that time the urgent requirements of

the Vietnam War had displaced cost effectiveness in priority within the

Department of Defense.15

-

-

- When McNamara became Secretary of

Defense the centralization of authority in the Office of the Secretary of

Defense was apparent in the number of agencies operating directly under

the Secretary or the joint Chiefs rather than under the

- [310]

- service departments. One of the

earliest of these was the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP),

an ad hoc interdepartmental, triservice organization, set up on 1 January

1947 by joint directive of the Secretaries of the Army and Navy as the successor

to the Manhattan District when the new Atomic Energy Commission took over

most of the latter's functions and facilities. AFSWP was a combined logistical

support, training, and combat developments agency for the military application

of atomic energy. Serving the Army, Navy, and later the Air Force it was

never a joint agency as such. It reported to the Secretaries of War and

Navy and later to the Secretary of Defense through the service chiefs.

-

- Following the Department of Defense

reorganization of 1958, the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project was redesignated

as the Defense Atomic Support Agency (DASA) and placed under the JCS. The

National Security Agency (NSA), created in 1952, continued to perform highly

specialized technical and coordinating functions in the intelligence area

under the direction of the Secretary of Defense. The Advanced Research Projects

Agency (ARPA) was created in February 1958 as a separately organized research

and development agency of the Department of Defense.

-

- The Defense Communications Agency

(DCA) was created on 12 May 1960 as an agency of the Department of Defense

responsible to the Secretary through the JCS for the "operational and

management direction" of the Defense Communications System, including

all Department of Defense "world-wide, long-haul, Government-owned

and leased, point-to-point circuits, terminals, and other facilities,"

to provide secure communications among the President, the Secretary of Defense,

the JCS, and other government agencies, the military services and departments,

the unified and specified commands, and their major subordinate headquarters.

-

- The first joint defense agency Secretary

McNamara established was the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), established

under the JCS by a directive on 1 August 1961 to "organize, direct,

and manage the Department's intelligence resources and

- [311]

- to coordinate and supervise such

functions still retained by the three military departments."16

-

- Nearly all these agencies transferred

some functions or activities of the Army, Navy, and Air Force to the Department

of Defense under the JCS. Another function Secretary McNamara wanted to

investigate, common supplies and services, affected the Army more directly.

The issue was whether the existing single manager system provided the most

effective means of integrating these activities. As outlined earlier this

system had been adopted as a means of avoiding complete integration under

a fourth service of supply and against considerable opposition from the

military services. They continued resistance to further integration, disagreeing

on what items should be classified as common supplies and services and on

the development of more uniform supply distribution procedures. Congress

continued to exert strong pressure for further if not complete integration

through a separate defense common supply and service agency.17

-

- On 23 March 1961 Secretary McNamara

asked Mr. Vance and the several Assistant Secretaries for Installations

and Logistics to study this question, which he labeled Project 100. They

were to investigate and list the advantages and disadvantages of (1) continuing

the existing single manager system operating under the several service secretaries,

(2) assigning responsibility for operating a consolidated supply and service

agency under one secretary, or (3) operating such a service under the Secretary

of Defense.18

-

- The Project 100 Committee submitted

its report on 11 July 1961. The principal weaknesses, it thought, of continuing

the existing system of multiple single managers were that the numerous channels

of command and staff layers required de-

- [312]

- layed decisions and impeded effective

control over operations. Any increase in the numbers of single manager assignments

would further complicate this problem, producing duplication and greater

diversity of procedures. Finally the single managers had to compete for

limited manpower and operating funds with other service functions.

-

- The principal disadvantages of consolidating

these functions under one department were that the service selected might

tend to favor its own programs and at the same time interfere in the supply

management of the other two services. It would also call for a major reorganization

with all the attendant confusion, disruption, and temporary loss of efficiency.

Interference in the supply management of the services and the disruptive

effect of a major reorganization were also disadvantages of setting up a

separate consolidated common supply and service agency. It might also be

less responsive to combat support requirements.19

-

- The committee recommended that whatever

organizational pattern was selected common supply and service functions

should remain a military responsibility because their sole purpose was to

support military operating forces. Such an integrated system should also

be adaptable to wartime use immediately. Each service should retain full

control over the development and management of its assigned weapons systems.

All of them would continue to require military personnel trained in supply

and service management. Common supply and services activities should be

restricted to wholesale distribution within CONUS, and the services should

retain their own retail distribution systems and facilities as under the

existing single manager systems.20

-

- The service chiefs and secretaries

split in their choice of alternatives. Secretary McNamara publicly announced

his decision on 31 August 1961 that a separate common supply and service

agency to be known as the Defense Supply Agency (DSA) would be established.

The Department of Defense directive issued on 6 November 1961 establishing

DSA, effective 1 January 1962, differed from the Project 100 Committee's

concept in two important respects. The committee thought

- [313]

- there should be a Defense Supply

Council composed of the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the service secretaries,

the chairman of the joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Assistant Secretary of

Defense for Installations and Logistics. This council would actively supervise

DSA's operations. Secretary McNamara made the council a purely advisory

agency and granted the director broad executive authority to run the Defense

Supply Agency. Second, he did not limit the choice of the director specifically

to a military officer as recommended by the committee. The man he chose,

however, was a former Quartermaster General of the Army, Lt. Gen. Andrew

T. McNamara. Finally, at the request of the JCS which did not want the responsibility

for DSA, Mr. McNamara ordered the director to report directly to him instead

of through the JCS as was the case with nearly all the other joint defense

agencies.21

-

- When the Defense Supply Agency was

set up, it took over the eight commodity single managers, the Military Traffic

Management Agency, the Armed Services Supply Support Center, the thirty-four

Consolidated Surplus Sales offices, the National Surplus Property Bidders

Registration and Information Office, the Army and Marine Corps clothing

factories, and the management of a proposed electronics supply center. DSA

was to administer the Federal Catalog Program, the Defense Standardization

Program, the Defense Utilization Program, the Coordinated Procurement Programs,

and the Surplus Personal Property Disposal Program.

-

- The Defense Supply Agency staff

included both military and civilian personnel from all services on a joint

basis, but 95 percent of its staff were civilians. Originally nearly 60

percent of its staff came from the Army, including most of the Quartermaster's

supply management personnel. By the end of June 1963, DSA was managing over

a million different items in nine supply centers with an estimated inventory

value of about $2.5 billion.

-

- In general DSA was to act as a wholesale

distributor of supplies to the services within the continental United States.

The military services would decide what they wanted, where they wanted it,

and when. DSA would decide how much to buy, how much to stock, and how to

distribute it to meet the

- [314]

- needs of the services. The services

retained responsibility for selecting those items which should be placed under

integrated management.22

- [315]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the

Table of Contents