CH-47 WITH M102 HOWITZER

CHAPTER III

In Order To Win

By late 1964 it was apparent that the South Vietnamese could not win the war alone despite heavy infusions of U.S. equipment and advisers. Most of the country was either firmly controlled or hotly contested by the enemy. The South Vietnamese Army weekly casualty rate was equivalent to a full battalion, a rate that could not be long sustained. To complicate matters further, the enemy was concentrating forces in II Corps Tactical Zone in preparation for a major offensive to cut the country in half at National Highway 19. Accordingly, President Lyndon B. Johnson, acting under authority of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, ordered U.S. combat forces to South Vietnam. The first troops, U.S. Marines represented by the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, arrived on 8 March 1965. They were followed two months later by the 173d Airborne Brigade. Combat troops would continue to arrive over the next three years until the total commitment was equivalent to over ten divisions-two Marine divisions, seven Army divisions, three separate brigades, and an armored cavalry regiment plus requisite control headquarters and support.

More than two battalions of field artillery would arrive in Vietnam for each combat brigade. One battalion would be in direct support of each brigade, and the remainder would provide augmenting fires or area protection. The very size of the field artillery indicated that it was being counted on heavily to provide a major portion of the combat power required to win. Artillerymen at all levels were challenged to insure that so large and important a force be employed to its maximum effectiveness.

If field artillery units were to be effective from the outset of their introduction to the war, they had to arrive in Vietnam well trained. In the United States, commanders of field artillery units alerted for deployment to Vietnam carefully planned and executed intensive training programs for their troops. There was little time and much to be done.

A minor part of the total training of all units consisted of instruction in subjects applicable to all branches. Headquarters, United States Continental Army Command, directed that a sixteen-

[38]

hour block of instruction consisting of the following subjects be given to all Vietnam-bound units:

Orientation-2 hours

Perimeter defense-1 hour

Duties of sentries-1 hour

Ambush drill, mounted and dismounted-8 hours

Field sanitation-1 hour

Jungle survival-1 hour

Lessons learned-1 hour

Miscellaneous-1 hour

The remaining training time was devoted to artillery-related subjects. All field artillery headquarters, from division artillery and artillery group down, underwent intensive training centered on employing their units against irregular forces. Battalions conducted section, battery, and battalion training which culminated, when possible, in field training exercises to test unit proficiency. Battery commanders emphasized platoon operations and gunnery and fire direction procedures in the 6,400-mil environment. They foresaw the need for additional fire direction center personnel in the event their battery weapons were split among several locations. As a result, time permitting, survey and howitzer crews were cross-trained in fire direction center procedures.

Because of leaves, reassignments, and last-minute arrival of replacements, classes and practical exercises often had to be conducted several times to insure that all personnel received the necessary training. Training for all units then continued aboard troop transports. Classes were presented for two hours daily. They were followed by twenty to thirty minutes of physical training, conducted during the warmest part of the day in order to acclimatize soldiers to tropical heat.

The Impact of Vietnam on Field Artillery Organizations

Not in recent history had the U.S. Army faced an insurgent force of such significance on terrain that so favored the enemy as in Vietnam. Since the enemy largely dictated how the war would be fought, it was necessary for the Army to modify established operational doctrine considerably to be successful against him. These modifications had a tremendous impact at all organizational levels. The impact on field artillery organizations is most readily explained by comparing the tactics used in fighting a conventional war with the tactics developed in Vietnam.

In a conventional ground war, U.S. maneuver forces are disposed along a line facing the enemy. To the front, security forces

[39]

are positioned to warn of the enemy's approach and to delay him while inflicting maximum punishment. To the rear, additional maneuver forces are held in reserve by all ground commanders above company level, and each is committed by its commander when needed.

Also to the rear are the combat support activities, including the field artillery, as well as combat service support activities. For the most part the rear area contains no large enemy forces, so units operating there are considered sufficiently strong to defend themselves. With little enemy ground activity, wire communications are used extensively in the rear area. Radio is considered a secondary means of communication, for the most part used by units on the move. The main threat to the survival of a unit is the enemy's fire power from aircraft and artillery that can reach behind the front lines.

Most of the available field artillery is used to engage the enemy forward of front-line maneuver forces; therefore, most artillery units, though as scattered and dispersed as possible, are disposed laterally behind the front line. Each maneuver division has artillery to support its ground forces, the composition depending on the type of division. In most cases the division artillery has three similar battalions of light or medium cannon artillery, sufficient to support each of the three brigades of the division, and one or more additional battalions of heavier artillery to provide augmenting fires.

The division artillery commander supports the division commander's maneuver plan by assigning missions to his artillery battalions and by coordinating the employment of all available fire support, including nondivisional field artillery and fire support from other branches and services. A field artillery unit can be assigned to support a single maneuver unit (it is then said to be in direct support), or it can be employed to augment the fires of other artillery units. In the latter case, a unit can have a reinforcing mission, augmenting the fires of a single designated field artillery unit; a general support mission, augmenting the fires of all field artillery units of the division; or a general support-reinforcing mission. A unit on this last mission again augments the fires of all field artillery units but gives priority to reinforcing the fires of a single designated artillery unit of the division.

Mission assignment has proved to be an extremely effective method of weighting the main effort of the division and economizing combat power elsewhere. It has provided the flexibility required for adjusting fire support to the ever-changing needs of the battlefield. Mission assignment has been particularly effective in conven-

[40]

tional operations, in which units can displace virtually at will to give maximum support to the ground forces.

In assigning missions to subordinate battalions, the division artillery commander first places one of his three light battalions in direct support of each committed brigade. Thus, if the division has two brigades on line and one in reserve, only the two brigades on line receive direct support artillery. The division artillery commander than assigns an augmenting mission to the third of this three similar battalions. Perhaps the most common mission for this battalion is to reinforce the direct support battalion covering the area of greatest effort or largest threat. At the same time, the reinforcing battalion is instructed to revert to direct support of the brigade in reserve when that brigade is committed to battle. The division artillery commander most commonly places his heavy artillery battalion in general support of the division or in general support-reinforcing of the fires of a specific direct support battalion. However the division artillery commander employs his battalions at the beginning of an operation, he is free to adjust them at any time to meet unforeseen developments.

In conventional operations, missions seldom are assigned to artillery units smaller than battalion. A battalion in direct support of a brigade supports the entire brigade rather than assigning one of its batteries to each of the brigade's battalions. To control the fires of its three batteries, the battalion establishes a centralized fire direction center. Centralized control permits the battalion to bring all the fires of its batteries to bear at any point in the brigade sector. This massing of fires is possible because all batteries are likely to be well within range of the entire brigade front. In fact, combat power might be so highly concentrated in some instances that all the artillery of a division can be massed on a single target.

Even so, there are occasions on the conventional battlefield where firing batteries or battalions are widely separated; for example, artillery units might be sent forward to support long-range screening or covering force operations, or units might be sent to support a force on an independent operation. Artillery organizations and doctrine have provided for such contingencies. Firing batteries have fire direction centers which under normal conditions provide backup support of the battalion fire direction center but act independently where the battery is too distant for its parent unit to control or support it. When a battery or battalion is distant from its parent unit, it is normally attached to its supported maneuver unit.

In a conventional battle plan before the Vietnam era, field artillery doctrine was that sizable amounts of field artillery, in addi-

[41]

tion to that organic to division artilleries, are available to support ground operations. This artillery is organic to a field army and is organized into separate battalions or groups. (A group controls two or more battalions.) The field army commander provides additional combat power to his subordinate corps by assigning his field artillery to them. He can thus effectively weight the combat power of the corps that he considers to have the highest priority, based on the mission he has given it. The corps commander receiving artillery from field army in turn assigns the artillery to augment his subordinate divisions. He also gives primary consideration to that division with the most critical mission.

The war in Vietnam was anything but conventional. The enemy was not contained by a line of friendly forces. Instead, he operated throughout the country, mostly in small units, but massing formidable strength when and where he chose. Accordingly, military ground operations were characterized by numerous, concurrent, widely dispersed small-unit operations. These tactics permitted continuous pursuit of the widely scattered enemy. To insure that the maximum area was defended by available troops, a section of terrain called an area of operations (AO) was assigned to each ground unit from the highest level down. A ground force commander conducted operations throughout his assigned area. The two field force commanders divided their areas, each corresponding to one of the four South Vietnamese military regions, among their divisions. The divisions in turn divided their territory into brigade areas of operations. Brigades split their areas among their battalions; battalions, among their companies.

The wide dispersal of maneuver forces required significant changes in the employment tactics of supporting artillery. The size of brigade areas of operations and range limitations of the cannons prevented a direct support battalion from massing the fires of its batteries in support of an entire brigade. Instead, artillery was disposed to provide the maximum area coverage, with each of the three batteries of a battalion in direct support of one of the three maneuver battalions of the brigade. The infantry battalion commander and the supporting battery commander were jointly responsible for insuring that the battery was always positioned to cover adequately all maneuver forces of the battalion.

Fire direction was no longer centralized at field artillery battalion but was decentralized to battery level or, when the battery was forced to occupy two positions, to platoon level. The primary justification for centralizing fire direction was the ability to mass

[42]

fires. Now that that ability no longer existed, the best place to control fires was at the battery, where the commander could best appreciate the needs of the supported infantry battalion. Firing batteries were isolated with their supported battalions. They did not have the freedom of movement they would have on the conventional battlefield but moved with their supported infantry battalions and were protected by these battalions. Wire communications were vulnerable, and radios were used exclusively for communicating beyond defensive positions. Because of the distances involved, a battery, without freedom of movement, could do little to support itself administratively or logistically without increased assistance from its parent battalion.

Small friendly units operating throughout the area of operations were difficult to pinpoint and added to the difficulties of providing supporting fires to ground forces. Artillery forward observers with maneuver companies continuously transmitted position locations to the battery, but the terrain made land navigation difficult and there was always the possibility of a mistake by the forward observer. Any mistakes could have resulted in friendly casualties. Out of respect for that danger, an infantry battalion commander rightfully restricted the activities of his direct support battery until its men had demonstrated their competence to his satisfaction. This took several weeks at best. Once his confidence was won, the commander loosened restrictions and the total combat system worked as it had been designed to work. Fires were planned and executed within general guidance from the ground commander, who was then free to devote his attention to the maneuver plan.

The artillery and infantry have always had a close working relationship, a requirement if maneuver and fire support are to be completely complementary. This relationship was never closer or more important than in Vietnam. The artillery battery was isolated with its supported infantry battalion. Each was dependent on the other for survival-the artillery for protection, the infantry for supporting fires. The relationship was further strengthened by a policy of "habitual association" of a direct support battalion with a specific brigade and each battery of the battalion with a specific maneuver battalion.

The policy of habitual association was logical and easily executed. Every maneuver brigade was committed to the defense of an area of operations; none was placed in reserve. For that reason, each of the three light battalions of division artillery was always in direct support of a brigade. So rigidly was the policy of habitual association enforced that an artillery battalion and its associated brigade

[43]

often entered the country at the same time, remained together throughout their involvement there, and withdrew from Vietnam or stood down together.

Vietnam also had its impact on the activities of the division artillery. With each of his light battalions in direct support of a maneuver brigade, the division artillery commander was powerless to vary their tactical mission or otherwise rearrange the support they provided. The only unit remaining with which he could influence the action was his heavy battalion, which generally consisted of three 155-mm. batteries and an 8-inch battery. He would direct the batteries of the heavy battalion to provide additional fires where he thought they were most needed. Often one of his 155-mm. batteries was committed to the direct support of the division cavalry squadron, reducing his flexibility to influence the action even more. Furthermore, distances and the situation prevented the division artillery commander from utilizing his remaining artillery as responsively as he could in conventional operations. Heavy artillery was positioned in advance of an operation and moved only infrequently, if at all.

Since the capability to influence the battle at division artillery level was reduced, the work load normally associated with the capability was also reduced. Yet as the responsibilities of the division artillery commander were lessened in one area, they were increased in others. The wide dispersal of artillery units increased the problems of supply and maintenance, and staff officers were kept busy seeking ways to increase the support the battalions could provide to their batteries. Trucks and helicopters for hauling supplies were sought out and requested. Needed maintenance and administrative support was arranged for battalions to send to isolated batteries. In addition, the division artillery commander was responsible for contributing forces, weapons, and equipment to the defense of the division base camp or for directing the entire base camp defense. Also, because winning the support of the population was so important to the success of a counterguerrilla war, added emphasis was placed on civil affairs and the work load in that area expanded considerably. Division artillery staffs were augmented with an officer to plan and direct civil affairs activities and to coordinate those of subordinate battalions.

The work load of the division artillery commander in other areas was much the same as it had always been. He was still the adviser to the division commander on fire support matters. Intelligence had to be gathered and collated continuously and actions of division maneuver forces and artillery updated. A fire support element at division had to be established to support ongoing maneuver

[44]

operations. And the use of nondivisional fire support means, including field artillery, Air Force tactical air and strategic bombers, and naval air and naval gunfire, had to be planned, requested, and coordinated.

As in conventional operations, there were large amounts of field artillery in addition to that organic to divisions; however, the manner in which it was organized and employed was vastly different. In a conventional operation, nondivisional field artillery normally is at the field army level and is apportioned to corps on the basis of their needs. United States Army, Vietnam (USARV), was organized into two field forces and a separate corps. The field force, a new organization to the Army, was roughly equivalent in level of command to a corps but had greatly expanded supply and administrative responsibilities. The corps, on the other hand, was a tactical headquarters and its lean staff could only coordinate logistical activities. In Vietnam, field artillery was assigned on a permanent basis to each of the field forces and the separate corps. This practice recognized that the requirements of each command tended to remain stable and that the long distances involved precluded continuous shifting of artillery from one field force to another. The stability of artillery requirements of the two field forces and the separate corps was a result of the mission assigned to nondivisional artillery. Whereas divisional artillery supported specific U.S. maneuver operations, nondivisional artillery served in an area support role, a role that was new to the field artillery yet vital under the circumstances.

Of overriding importance in Vietnam, as in any counterguerrilla action, was winning the support of the people for their government. They had to be shown that the government could improve their lot as well as protect them from the insurgent. Field force artillery firing units were positioned to provide maximum coverage of population centers, lines of communication, and government installations. Firing units answered calls for fire support from any friendly party, civil or military, within range. The position location of each unit had to be carefully planned in relation to the position locations of all others. This planning was done at field force level. In past wars commanders at such high levels were not concerned with the positioning of individual firing units; subordinate artillery commanders had the authority to decide within liberal territorial limitations where units could best be placed to perform their mission. But in Vietnam much of the responsibility for positioning their units was taken from them.

As was true of division artillery, commanders of groups and battalions in field force artillery had increased work loads in other

[45]

areas as a result of added logistical support problems and civil affairs and position defense responsibilities. Also, the role of nondivisional artillery created a requirement for continuous dialogue with local government representatives and supported military and paramilitary forces. Such dialogue was necessary not only for the artillery to do its job but also for its survival. Firing units providing area cover were often far from U.S. maneuver forces and had to turn to the Vietnamese for protection.

Commanders of both division and field force artillery in Vietnam continued the practice of providing fire support through mission assignment, though the meanings applied to the missions were somewhat changed. Since units were so widely dispersed, a single artillery unit normally could not be positioned to augment the fires of several other artillery units. Instead, general support became area coverage. For units of divisional artillery, area coverage placed primary importance on plugging gaps in the coverage of direct support units. For units of field force artillery, area coverage placed primary importance on supporting all friendly forces within range of their positions. Thus, quite contrary to its normal meaning, the mission of general support was often given to a unit that had no other field artillery within range. The meaning of the reinforcing mission changed little. Reinforcing artillery still augmented the fires of a specific artillery unit. General support-reinforcing artillery was positioned to augment the fires of a specific field artillery unit but otherwise provided area coverage.

Another change occurred in respect to batteries too distant from their parent battalions to receive control or support. Practice in the past had been to attach such batteries to their supported maneuver battalions, but in Vietnam such an arrangement was not fully satisfactory. Maneuver commanders had neither the equipment nor the expertise to support artillery units adequately, particularly for lengthy operations. And field artillery commanders, who were schooled and experienced in the employment of artillery to serve the maneuver forces best, were unable to influence the situation. Instead of attachment, the status of operational control (OPCON) was most often used. For example, if a firing battery was to be separated from its parent headquarters, it was placed under the operational control of another artillery battalion headquarters in the area in which the battery was employed. A battery that was under the operational control of a field artillery battalion was controlled by that battalion but continued to receive support from its parent battalion. Maneuver commanders could then receive the best possible fire support without being burdened with additional support requirements.

[46]

Though operational control served a useful purpose, its use complicated operations of battalions with both divisional and nondivisional artillery. At any one time, one battalion might be controlling its own three batteries plus several others that were under its operational control. Another battalion might have lost the operational control of all its organic batteries to another battalion. Artillery battalions had to be flexible enough to direct the operations of a varying number of batteries.

On numerous occasions artillery units were employed in ways quite contrary to the general practice that had been developed in Vietnam. Division artillery normally supported divisional maneuver forces whereas field force artillery served in an area support role. Yet on any one day during the height of the U.S. commitment, one could point out numerous cases in which roles were reversed. For example, when division artillery supported divisional maneuver units in such rugged terrain that its organic 155-mm. selfpropelled howitzers could not follow, the division artillery commander might be provided with airmobile 155-mm. towed howitzers from field force artillery for the duration of the operation. There were also frequent occasions when field force artillery units were placed in direct support of maneuver units, and many times division artillery units provided area support.

The responsibility for coordinating the various types of fires available to the maneuver commander falls largely on the field artillery. At all maneuver headquarters above company level, an artillery fire support coordinator (FSCOORD) is responsible for coordinating all available fire power-field artillery, armed helicopters, Air Force and Naval tactical air, air defense weapons in the ground support role, and naval gunfire. In addition, an infantry battalion commander often delegates responsibility for coordinating the battalion heavy mortar fire to his coordinator At maneuver company, the company commander is the fire support coordinator though a field artillery forward observer is available to aid and advise him. At maneuver battalion the coordinator is a liaison officer from the direct support field artillery battalion. At higher levels he is the commander of the artillery supporting the force; however, in practice he delegates the detailed coordination activities to a subordinate. The artillery battalion commander delegates the duty to the artillery liaison officer with the brigade. The division and corps (or field force) artillery commanders delegate the duty to an assistant coordinator Within each of the operation centers of

[47]

maneuver forces, a coordinator establishes and supervises a fire support coordination activity, called a fire support coordination center (FSCC) at battalion and brigade level and a fire support element (FSE) at division and higher. In the center are representatives of all available fire support units. Some representatives are not included in the fire support element, being normally found elsewhere in the tactical operations center; but their presence in the center still allows efficient coordination

The field artillery liaison officer (now titled the fire support officer) with either a maneuver battalion or brigade was tasked in Vietnam as never before. Because of advances in weapon technology, more types of fire support were available. To complicate matters, each type of fire support could deliver a host of different munitions, each designed for a different job. The field artillery liaison officer was the one who insured that the most appropriate ordnance available arrived at the right targets at a specified time and that all the fires delivered complemented one another. Besides having more weapons to coordinate, he often had to support not only U.S. Army forces but also Vietnamese military and paramilitary, Korean, Australian, Thai, New Zealand, Philippine, and U.S. Marine forces during joint operations. That task required more than processing and passing requests to the appropriate support means; it required establishing priorities as well as insuring that the organic fires of the other force were coordinated with the support being requested. This frequently called for him or an Army forward observer to be on the scene to request and direct or coordinate the fires. His efforts were further complicated by differences in language and in operating procedures.

As if such complications were not enough, he was required to obtain clearance to insure that no civilians were in the area before employing weapons. Clearance was most often obtained from the government district in which the supported force was operating, and arrangements had to be made to open and maintain the necessary radio nets in advance of an operation. Clearance had not been required in past U.S. wars, in which the enemy was engaged forward of a battle line and was not operating among the friendly population. Another responsibility of the liaison officer that was peculiar to Vietnam was the coordination of air space usage. Artillery warning control centers (AWCC's) were established, normally at maneuver battalion and brigade levels, to advise the numerous aircraft over the area of operation of current supporting fires. All support means were required to notify the warning center before firing. Aircraft entering the area would, in turn, contact the center

[48]

and receive current information plus a flight path to follow to avoid firings.

The wide variances in the types of field artillery weapons sent to Vietnam gave senior artillery commanders great flexibility in tailoring fire support to satisfy best the needs of the situation.

The 105-mm. towed howitzer most often served in the direct support role. Its light weight, dependability, and high rate of fire made it the ideal weapon for moving with light infantry forces and responding quickly with high volumes of close-in fire. Units were initially equipped with the M101A1 howitzer, virtually the same 105-mm. howitzer that had been used to support U.S. forces since World War II. In 1966 a new 105-mm. towed howitzer, the M102, was received in Vietnam. The first M102's were issued to the 1st Battalion, 21st Field Artillery, in March 1966. Replacement of the old howitzers continued steadily over the next four years.

Many of the more seasoned artillerymen did not want the old cannon replaced. Over the years they had become familiar with its every detail and were confident that it would not disappoint them in the clutch. Old Redlegs could offer some seemingly convincing reasons why the M101 was still the superior weapon: its waist-high breech made it easier to load; it had higher ground clearance when in tow; but most important, it was considerably less expensive than the M102. Their arguments, however, were futile. The new M102 was by far the better weapon. It weighed little more than 1 1/2 tons whereas the M101A1 weighed approximately 2 1/2 tons; as a result, more ammunition could be carried during heliborne operations, and a 3/4-ton truck rather than a 2 1/2-ton truck was its prime mover for ground operations. Another major advantage of the M102 was that it could be traversed a full 6,400 mils. The M101A1 had a limited on-carriage traverse, which required its trails (stabilizing legs) to be shifted if further traverse was necessary. A low silhouette made the new weapon a more difficult target for the enemy, an advantage that far outweighed the disadvantage of being somewhat less convenient to load.

Certain field force artillery units were equipped with the M108, a 105-mm. self-propelled weapon. The weapon was obsolescent but was still in the U.S. field artillery inventory. In Germany, it had been replaced by the 155-mm. self-propelled howitzer as the direct support artillery for U.S. armored and mechanized divisions. The M108 was too heavy to be lifted by helicopter, so its support of

[49]

highly mobile light infantry forces in Vietnam was restricted. Still, the M108 was employed effectively in the area support role and, if the terrain permitted, in support of ground operations.

The next larger caliber artillery weapons were the 155-mm. howitzers. Firing units were equipped with either the towed M114A1 or the self-propelled M109. Both weapons normally provided area coverage or augmented direct support artillery. Occasionally, however, the 155-mm. self-propelled howitzer was used in direct support of maneuver units, as with the 1st Brigade, 5th Mechanized Division. Or when a divisional cavalry squadron operated as an entity, it was often provided a 155-mm. battery for direct support. Like the M108, the towed M114A1 was considered obsolescent. It was no match for the 155-mm. self-propelled weapon for supporting conventional ground operations against a highly mobile, armor-heavy enemy. In Vietnam, however, the M114A1 proved invaluable because it was light enough to be displaced by helicopter and so could provide medium artillery support to infantry forces even where roads were nonexistent. The 155-mm. howitzers, whether towed or self-propelled, had a maximum range of 14,600 meters, over 3,000 meters greater than that of the 105-mm. howitzer. The weight of the 105-mm. projectile-95 pounds-was almost three times the weight of the 105-mm. projectile. For these reasons, the 155-mm. howitzers could provide a welcome additional punch to existing direct support weapons.

The M107 self-propelled 175-mm. gun and the M110 8-inch howitzer had identical carriages but different tubes. The 175-mm. gun fired a 174-pound projectile almost 33 kilometers. This impressive range made it a valuable weapon for providing an umbrella of protection over large areas. The 8-inch howitzer fired a 200-pound projectile almost 17 kilometers, plus being the most accurate weapon in the field artillery. The 8-inch howitzer was found with most division artilleries, and both the 8-inch howitzer and 175-mm. gun were with field force artillery. At field force the proportion of 8-inch and 175-mm. weapons varied. Since the weapons had identical carriages, the common practice was to install those tubes that best met the current tactical needs. One day a battery might be 175mm.; a few days later it might be half 175-mm. and half 8-inch.

Aerial rocket artillery (ARA) proved to be extremely effective in augmenting and extending the range of the cannon artillery of the airmobile divisions. Aerial rocket artillery units initially employed the UH-1B or UH-1C (Huey) helicopter equipped with a weapon system that could carry and fire forty-eight 2.75-inch rockets. In early 1968 the improved AH-1G (Huey Cobra) was outfitted as an aerial rocket artillery aircraft. Its maximum speed of

[50]

130 knots was some 30 knots faster than that of the Huey. In addition, it carried a larger payload of 76 rockets. In early 1970 the designation of aerial rocket artillery was changed to aerial field artillery (AFA). By either name, it was in every sense a field artillery weapon system, organized as such and controlled by artillerymen through artillery fire support channels.

The importance of mobility in insurgency operations cannot be too highly stressed. From experience in past guerrilla actions in Malaya and the Philippines, the conclusion was that at least ten soldiers are required to counter every enemy soldier. The ratio is high because the enemy has the initiative. He can hit wherever he desires and thus require that friendly forces be ready in sufficient numbers at all locations likely to be contested. Once the enemy has attacked and withdrawn, sizable forces are needed to sweep the countryside if there is to be any hope of finding him. Superior mobility allows the available friendly units to be more widely deployed and permits planners to reduce the ratio of friendly to

[51]

CH-54 LIFTING 155-MM. HOWITZER

enemy troops. For example, a highly mobile infantry battalion and its supporting battery could complete an operation in one area and in a matter of hours be moved to another some distance away.

Mobility in Vietnam for ground troops and artillery alike was provided by ground vehicles, Air Force assault aircraft, watercraft, and helicopters. More artillery was moved by road than by any other means. When a landing zone could be conveniently reached by road, it was to a unit's benefit to move in this fashion if operational considerations did not dictate otherwise. The unit could be moved in convoy by its own vehicles and in its entirety, whereas movement by helicopter usually required several lifts. Because of its weight, all self-propelled artillery was moved in convoy. The Air Force, usually employing C-130's, supported long-distance moves between improved or unimproved airstrips. Watercraft transported both infantry and artillery in the delta areas, where a network of rivers, rivulets, and canals favored such movement.

The Vietnam war saw the first large-scale use of helicopters by the U.S. Army to transport troops, artillery, and supplies. Helicopters added a new dimension to the battlefield by providing the

[52]

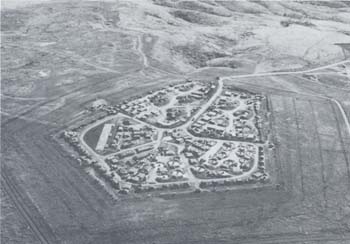

FIRE SUPPORT BASE J.J.CARROLL IN MILITARY REGION I. A large fire support

base, J.J. Carroll contained four firing units.

commander a more responsive and flexible means to concentrate his combat power where it was needed.

Before 1962, the helicopter had been used sparingly, but through the imagination and drive of several key officers, notably Generals James M. Gavin and Hamilton H. Howze, the airmobile concept was developed. They envisioned the deployment of lightly equipped troops by lift helicopters, with fire support to and within the objective area provided by light tube artillery and armed helicopters. What airmobile troops lacked in weight they would compensate for with mobility. They were planned for use against a sophisticated enemy where highly mobile forces have always been needed. Covering force and screening operations, economy-of-force missions, flank and rear area security, and securing of key terrain, bridges, and installations behind enemy lines were a few possible applications. In 1962 the Airmobility Requirement Board (commonly known as the Howze Board) was formed to develop organizational requirements for an airmobile brigade. The efforts of the board resulted in the activation of the 11th Air Assault Division, which was redesignated the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) in June 1965 and programed for deployment to Vietnam. Though the division was initially configured for use in a sophisticated environ-

[53]

STAR FORMATION. Battery B, 1st Battalion, 77th Field Artillery, in well-prepared

base camp.

ment, it proved to be extremely effective in Vietnam against an unsophisticated enemy.

The airmobile division artillery was equipped with 105-mm. towed howitzers and UH-1B (Huey) helicopters armed with rockets. Howitzers were lifted by the division's own CH-47A (Chinook) medium-lift helicopters. The Chinook could carry 33 combat troops and internal cargo up to 78 inches high, 90 inches wide, and 366 inches long or external cargo of 6,000 to 8,000 pounds, depending on atmospheric conditions. A 105-mm. howitzer battery with a basic load of ammunition could be moved in as few as 11 CH-47A sorties. Other maneuver units that followed the 1st Cavalry Division also used Chinooks extensively to move their howitzers; however, with the exception of the 101st Airborne Division these helicopters were not part of the divisions but were provided by aviation groups supporting the military regions. Every infantry unit in Vietnam was, in fact if not in name, airmobile infantry and its direct support artillery was airmobile artillery.

The CH-54 (Tarhe), nicknamed the Crane for its lifting ability, followed the Chinook to Vietnam. It could lift up to 18,000

[54]

pounds either by sling or by an attachable pod, but sling loads were by far the more common in Vietnam. Of special importance to the field artillery was the Crane's capacity to lift the 155-mm. towed howitzer without breaking it down into two separate loads as was required for the CH-47 helicopter. This would expedite the positioning of medium artillery in areas not accessible by road.

Cannon artillery is the only nonorganic fire support serving maneuver forces that is immediately responsive, always available, and totally reliable. It is immediately responsive because it is positioned to be always within range of the supported force, whereas other fire support means most often must be brought to the battle area or moved within range. It is always available because it is organized to provide field artillery in direct support of every committed maneuver force. A maneuver commander may not always receive other fire power because it is apportioned according to the needs of all commanders. It is totally reliable because it can function in any weather and in poor visibility, when helicopters and planes are grounded or their effectiveness is reduced.

Infantry commanders fully appreciated the value of field artillery support. In developing their maneuver plans, they worked closely with their supporting artillery commanders to insure that the plans could be fully supported by the artillery. If plans envisioned that maneuver battalions would be so widely dispersed that they could not be supported by direct support batteries operating from single battery positions, additional artillery was requested. If additional artillery was unavailable, the direct support batteries were split to occupy several positions and thereby increase area coverage even though fire power was reduced. Only on rare occasions did maneuver forces in Vietnam operate beyond the range of friendly artillery.

Use of available mobility allowed direct support artillery to follow supported ground forces virtually anywhere. But once field artillery was displaced to a preplanned position to provide supporting fires, it was extremely vulnerable to the enemy, who could attack in mass from any direction. Firing batteries had neither the personnel nor the expertise to defend their positions against determined enemy attacks. Accordingly, infantry units provided defensive troops. The position jointly occupied by supporting artillery and defending infantry was referred to as a fire base or fire support base. It was commanded by either an infantryman or an artilleryman, usually whoever was the senior. From its fire base an artillery fire

[55]

MEN FROM BATTERY A, 2D BATTALION, 319TH FIELD ARTLLERY, BUILDING PARAPETS

unit could shoot in any direction to its maximum range and would answer calls for fire support from maneuver forces operating under its protective umbrella.

The position for a fire base was selected jointly by the artillery and infantry commanders. The primary concern of the artillery commander was that the position be adequate to support maneuver elements throughout the area of operation. An important consideration was the availability of other artillery within range of the position that, if required, could be called on to provide indirect fire in defense of the fire base. Other important considerations were the type of soil to support the howitzers and how readily the position could be defended and supplied by air. The primary concern of the infantry commander was defense of the position unless he intended to establish his headquarters on the fire base to take advantage of the available security. In that event, he was concerned that the fire base be central to his maneuver forces so they could be effectively controlled. This priority was generally agreeable to the artillery commander, who could provide better all-round coverage from such a location.

[56]

1ST BATTALION, 40TH FIELD ARTILLERY, IN POSITION ALONG DEMILITARIZED ZONE

TYPICAL TOWED 155-MM. POSITION. Note trail blocks.

[57]

BATTERY C, 2D BATTALION, 138TH FIELD ARTILLERY, ON HILL 88, March 1969.

Because of the manpower drain on maneuver units had they been required to defend all artillery positions, fire bases were constructed almost exclusively for direct support artillery. When such a fire base was established, it was usually to support a large operation of at least divisional size or to provide a position when no available one was even marginally acceptable. Division or field force artillery generally chose the best positions for their firing units not in direct support from among defensive positions already established. As a result, such a unit might occupy a fire base with one or more other artillery units or, for that matter, might occupy any other type of defensive position belonging to either American or allied forces. Any commander was happy to have the additional fire power that a battery would bring to his position.

The organization of a fire base was a reflection of the flexibility and ingenuity of the American soldier. Terrain, area available, and number and caliber of weapons, plus numerous other variables, made it impossible to standardize procedures for occupying such positions. Still, some generalities can be cited.

The formation of artillery pieces on the ground varied with the

[58]

BATTERY D, 3D BATTALION, 13TH FIELD ARTILLERY, AT FIRE SUPPORT BASE STUART,

JUNE 1969. Chain link fence has been installed for protection against B40

rockets.

terrain and the caliber and number of weapons. Insofar as possible, weapons were arranged in a pattern with as much depth as width to eliminate the need for adjusting the pattern of effects on the ground. Six-gun batteries, which included all 105-mm. and 155-mm. batteries, were emplaced in a star formation, with five guns describing the points of the star and the sixth gun in the center. This configuration provided for an effective pattern of ground bursts and for all-round defense. At night the center piece could effectively fire illumination while the other pieces supported with direct fire. Firing units with only three or four guns arranged their pieces in a triangular or square pattern, if terrain permitted. The diamond formation was most commonly used by composite 8-inch and 175mm. batteries. The 175-mm. guns were positioned farthest from the center of the battery, where the fire direction center and administrative elements were located, thus reducing the effects of blast on personnel, equipment, and buildings.

The infantry established a perimeter as tight as feasible around the guns. The desired configuration was a perfect circle, but this was seldom possible because of the varied terrain to be defended. Perimeter defensive positions were dug in and bunkered where possible. To the front, barbed wire was strung and claymore mines arid trip flares were emplaced. Infantry soldiers defended the fire

[59]

155-MM. HOWITZER POSITION USING SPEEDJACK AND COLLIMATOR. Speedjack is under

center of howitzer, collimator to the rear of howitzer on sandbags.

base perimeter with their individual rifles and grenade launchers and with crew-served machine guns and recoilless rifles. In addition, the infantry was equipped with both 81-mm. and 4.2-inch mortars. Mortars were invaluable for fire base defense, not only for their heavy volumes of high-explosive fires but also for close-in illumination during enemy night attacks. A fire base was fortunate if it had air defense weapons on its perimeter. Both the M42A1"Duster," a dual 40-mm. weapon, and the M55 (quad), four .50caliber machine guns fired simultaneously, provided impressive ground fires, though neither weapon had been designed for that role. These weapons were organic only to nondivisional air defense battalions and were not available in sufficient numbers to provide protection to all fire bases.

The defense responsibilities of the infantry did not end with the establishment of a strong defensive perimeter. Just as important was aggressive and continuous patrolling around the fire base to frustrate enemy attempts to reconnoiter the base and prepare for an attack. Usually, a single-battery fire base was provided a rifle com-

[60]

pany to man the perimeter and conduct necessary patrols. This provision was recognized in the organization of infantry battalions in Vietnam, where each battalion was assigned four rifle companies instead of only three.

The field artillery on the fire base also contributed to its defense. In fact, the contribution of the artillery was often the deciding factor in staving off a determined attack. Artillery defensive fires included direct fire, countermortar fire, and mutually supporting fire.

Direct fire, as its name implies, required line of sight between weapon and target. It involved the use of special antipersonnel munitions and techniques. The XM546 antipersonnel projectile, called the Beehive round, was particularly effective in the direct fire role. The projectile was filled with over 8,000 flechettes, or small metal darts. The field artillery direct fire capability was integrated with the infantry defense to cover likely avenues of approach and the most vulnerable areas. It was imperative that the infantry bunkers be built up in the rear so that the infantrymen were protected from the effects of the Beehive ammunition. Beehive was fired in combat for the first time on 7 November 1966 by Battery A, 2d Battalion, 320th Field Artillery. A single round killed nine attacking enemy and stopped the attack. The round was employed on many occasions with similar success, perhaps the best known being during the enemy attack on Landing Zone BIRD.

Another effective direct fire technique was "Killer Junior," perfected by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Dean, commander of the 1st Battalion, 8th Field Artillery, of the 25th Infantry Division Artillery. The technique was designed to defend fire bases against enemy ground attack and used mechanical time-fused projectiles set to burst approximately 30 feet off the ground at ranges of 200 to 1,000 meters. The name Killer Junior applied to light and medium artillery (105-mm. and 155-mm.), whereas "Killer Senior" referred to the same system used with the 8-inch howitzer. This technique proved more effective in many instances than direct fire with Beehive ammunition because the enemy could avoid Beehive by lying prone or crawling. Another successful application of the Killer technique was in clearing snipers from around base areas. The name Killer came from the radio call sign of the battalion that perfected the technique. To speed the delivery of fire, the crew of each weapon used a firing table containing the quadrant, fuze settings, and charge appropriate for each range at which direct fire targets could be acquired.

Countermortar (or counterbattery) fires, the second type of artillery defensive fire, were preplanned, unobserved fires that were

[61]

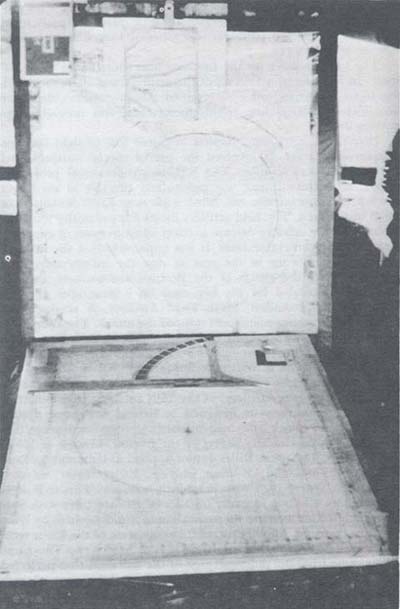

6,400-MIL CHART. Map on back shows area coverage.

[62]

[63]

[64]

[65]

[66]

[67]

executed in the event the fire base underwent an enemy rocket or mortar attack, either as part of a ground attack or as a "standoff" attack using rocket or mortar fire alone. A field artillery forward observer or liaison officer chose likely positions for enemy weapons from a map and from information provided by aerial reconnaissance. Firing data to the positions were computed and a fire plan was prepared. The fire plan was retained in the battery fire direction center, where it could be executed immediately when requested. This procedure might at first glance appear to depend

[68]

ARTILLERY HILL AT PLEIKU. An artillery base camp containing a field artillery

group, three field artillery battalion headquarters, and nine firing units.

to a great extent on luck, but it proved to be quite effective. An experienced artilleryman knowing the optimum range of enemy weapons, the likely routes into the area, and the criteria for good weapons positions could be very accurate in predicting future locations of enemy weapons.

Mutually supporting fires, the third type of artillery defensive fire, were indirect fires provided by one fire base in support of another. Whenever a new base was established, field artillery forward observers and liaison officers contacted responsible personnel on other bases within range and made plans to support one another if attacked. Planning included choosing and prefiring targets close to the defensive perimeter of each fire base. The firing data were retained in the fire direction centers and used when requested. Immediately available close-in fires were thus assured. Subsequent corrections could be made if necessary.

Time and again the indirect fires from mutually supporting artillery proved to be a principal factor in successfully countering an

[69]

enemy attack on a fire base. Having mutually supporting bases was considered so important that whenever a battery was required to occupy a position beyond the range of any friendly artillery, every effort was made to readjust other artillery positions to bring them within range. If that was not possible, batteries often split into three-gun platoons and occupied two separate but mutually supporting positions.

The various designs of individual weapon emplacements constructed by batteries on fire bases reflected a great deal of initiative and individuality. The design normally was standardized within a battalion and, in some cases, throughout a division or group. Whatever the design, it provided for all-round protection of weapons and crews from direct fire, readily available overhead cover for the crews, and protection of ammunition. Common materials used were sandbags, ammunition boxes, powder canisters, pierced-steel planking, heavy timbers, and corrugated steel roofing. Steel culverts covered with sandbags were used to provide hastily constructed, yet effective, personnel cover. Standard cyclone fencing placed 20-25 feet in front of positions protected howitzers, which, with their high silhouettes, were particularly vulnerable to enemy rocket attack.

The loose soil of coastal areas and the saturated soil of the lowlands during the monsoons made it difficult to prevent the shifting of light and medium howitzers during firing. Logs were used to brace the M101Al 105-mm. howitzers. Firing platforms on the M102 105-mm. howitzers frequently were staked through piercedsteel planking or ridged-aluminum planking. The M114A1 155-mm. howitzer was particularly prone to shifting. A common field expedient to help stabilize this weapon was 55-gallon drums filled with soil and buried vertically and flush with the surface. Logs were often dug in horizontally in a circle around the weapon to brace its trails during firing. One method that proved effective in reducing displacement was devised by the 1st Battalion, 84th Artillery. Old tank tracks with the ends linked together were buried vertically flush with the surface and in a circle. The howitzer was positioned in the center, with its trails against the tracks.

The 6,400-mil environment required that gun sections be thoroughly versed in techniques to allow weapons to be shifted rapidly to a new direction of fire. Two sets of reference points, which normally consisted of two sets of aiming posts or one set of aiming posts and an infinity collimator, provided a visible angular reference in any direction. Azimuth markers or stakes around the gun positions provided easy reference and facilitated the frequent shifting of trails from mission to mission. In the case of the 155-mm. towed howitzer, shifting trails was a time-consuming, laborious

[70]

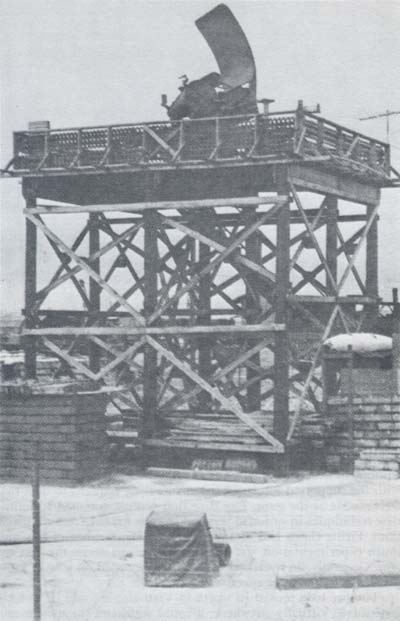

AN/MPQ-4 COUNTERMORTAR RADAR, positioned on a large tower for better area

coverage.

[71]

TPS-25 GROUND SURVEILLANCE RADAR

task. Through the initial efforts of Lieutenant Nathaniel Foster of the 8th Battalion, 6th Artillery, 1st Infantry Division, a pedestal that eliminated the need for lowering the howitzer off its jack before shifting trails was developed. Modification of Fosters initial platform led to the float jack, which made the weapon more responsive and flexible.

Central to the firing battery was the fire direction center. This was a small, well-bunkered position. It had the personnel and equipment necessary to receive fire requests from forward observers with the supported force and to convert these requests to data that were usable at the guns. Fire direction centers, too, had to follow new techniques in order to respond to calls for fire from all directions. Firing charts had to allow for a 6,400-mil range of fire, and much experimentation was done in this area to devise the best system. Generally, an oversized firing chart mounted on a large table proved to be the most effective solution.

The fire base proved its worth in Vietnam: it could be quickly constructed virtually anywhere; it could withstand the most formidable assaults that an unsophisticated enemy could bring against it; and it permitted the field artillery to provide fire support of the same high quality as that provided in past wars.

[72]

The base camp was an installation occupied by a headquarters larger than a battalion. Whereas the fire base performed a combat mission, the base camp was larger and contained controlling headquarters for combat activities as well as essential combat service support activities. A perimeter of bunkers encircled the base camp, and beyond the bunkers were intricate barriers of barbed wire reinforced with flares and mines. Headquarters and combat service support personnel, augmented where required by infantry, manned the perimeter. Ground forces conducted continuous patrolling around the base camp, usually out as far as the range of enemy rockets.

The field artillery also contributed to the defense of a base camp. Cannons fired harassing and interdiction fires on likely enemy routes and positions, answered calls for observed fire from patrols, fired illumination rounds, and provided direct fires against enemy ground attacks. The number of cannons required for the defense of base camps varied; a brigade or artillery group base camp might require only a platoon of artillery, whereas a division base camp might need several batteries.

In addition to cannons, field artillery targeting devices such as radars and searchlights, when available, were integrated into the defense. The AN/MPQ-4 countermortar radar, organic to direct support artillery battalions, and the AN/TPS-25 ground surveillance radar, organic to division artillery, were used in conjunction with shorter range infantry antipersonnel radars for locating targets. Once targets were located, they were engaged by cannons or other suitable supporting fires. Searchlights provided either visible or infrared illumination. They were oriented for direction on the same angular reference as the artillery weapons. If the enemy was spotted, an azimuth and an estimated distance could be relayed directly to the battery fire direction center.

The responsibility for defense of a base camp was often assumed by the senior artilleryman occupying the installation. Phu Loi base camp, for example, was occupied by the 23d Artillery Group headquarters plus other combat support and combat service support activities. No infantry unit was permanently assigned, and on two occasions the group commander was designated as Phu Loi defense commander. Senior ground commanders at times also delegated responsibility for the defense of their base camps to their senior artillery commanders, as in the 4th Division, first at Camp Enari and later at Camp Radcliff. As installation defense commander the division artillery commander controlled that area around the base

[73]

3O-INCH XENON SEARCHLIGHT. Battery I, 29th Field Artillery, at Fire Support

Base Horseshoe, February 1970.

[74]

camp within a fourteen-kilometer radius. He coordinated patrol and reconnaissance activities in the area, coordinated the perimeter defense effort, and established the installation defense coordination center, in which all efforts concerning reconnaissance, ground defense, reaction to enemy attack, target acquisition, and fire support were centralized. Sizable portions of base camp defense responsibilities were also delegated to the artillery commanders of the 1st Cavalry Division and the 1st Infantry Division. The former was given operational control of a cavalry battalion in Area of Operations CHIEF, encompassing the division base camp at Phuoc Vinh. The latter directed maneuver operations around the Big Red One artillery base camp at Phu Loi.

The terrain of the Mekong Delta was a serious hindrance to fighting forces in Vietnam. The delta is comprised of rivers and canals coupled with swamps and rice paddies. Roads and dry ground are scarce, and hamlets and villages have long since been built on what little dry ground there is. If artillery shared dry ground with a hamlet, the firing unsettled the people whose support the allies were trying so hard to win. Even when field artillery was positioned on dry ground, it was difficult to employ because the high water table made the ground soft. Without a firm firing base, cannons bogged down, were difficult to traverse, and required constant checks for accuracy. All this lessened their responsiveness and effectiveness.

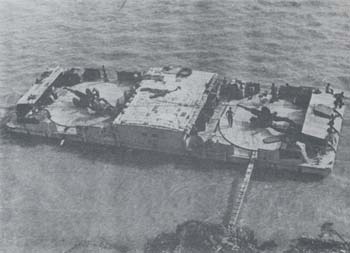

A fighting force in the delta could not rely on ground vehicles for transportation or supply. Vehicles could seldom move the infantry close to the enemy, they were vulnerable to ambush, and the scarcity of dry ground overly cramped and restricted supply operations and the activities of control headquarters and supporting field artillery. Helicopters were used successfully to transport troops and artillery to the area of operations. The airborne platform was developed to solve problems of the inadequacy and scarcity of dry ground. The platform, a 22-foot square, was similar to a low table with large footpads on four adjustable legs to distribute its weight. The platform could be lifted by Chinook and placed rapidly in boggy or inundated areas. A second Chinook brought in a 105-mm. howitzer M 102 and ammunition and placed it on the platform. (The howitzer and platform could be lifted together by a CH-54 Crane.) The platform provided space for the howitzer, the crew, and a limited amount of ammunition and permitted traverse of the howitzer in all directions. If one or more of the legs was mired when

[75]

CH-47 EMPLACING AIRMOBILE FIRING PLATFORM

the platform was to be moved, the footpad was disconnected and left in place to be recovered separately. A principal disadvantage of the airmobile platform was that the gun crew was overexposed to enemy fire. It was impossible to construct bunkers or overhead cover since the nearest ground was under water, though sandbags positioned around the edge of the platform provided some protection. Another disadvantage was that ammunition resupply and storage was difficult because of limited space on the platform.

Even more significant than the use of helicopters in the delta was the formation of a riverine task force, which relied on watercraft to provide transportation, fire power, and supply. The task force consisted of the 2d Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division and the U.S. Navy River Assault Flotilla 1.

Field Artillery support for the new riverine task force was initially provided from fixed locations, but the support was less than adequate. Field artillery needed to move and position itself to best support the ground action. This need was satisfied by the 1st Battalion, 7th Artillery, in December 1966 when the battalion first employed the LCM-6 medium-size landing craft as a firing platform for howitzers. The LCM could be moved to a desirable position and secured to the riverbank. Internal modification was required so that the craft could accommodate the M101A1 howitzer,

[76]

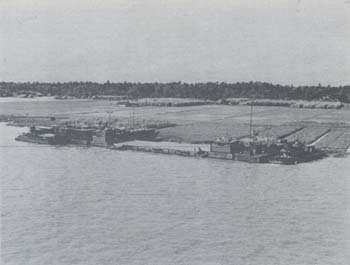

RIVERINE FIELD ARTILLERY BATTALION COMMAND POST, with fire direction center

on left, helicopter pad in center, and living quarters on right.

but even then it was not wide enough to permit the howitzer trails to be spread fully. As a result, the on-carriage traverse was limited. Other shortcomings were that the craft did not afford as stable a firing platform as was desired and that excessive time was required to fire.

More successful were floating barges. The concept originated from a conference in the field between Captain John A. Beiler, commander of Battery B, 3d Battalion, 34th Artillery, and Major Daniel P. Charlton, the battalion operations officer. Their ideas prompted a series of experiments to determine the most suitable method of artillery employment with the riverine force.

The first experiment used a floating AMMI ponton barge borrowed from the Navy and an M101A1 105-mm. howitzer. Although the AMMI barge served its purpose, it was difficult to move and had a draft too deep for the delta area. The barge finally used was constructed of P-1 standard Navy pontons (each 7 by 5 feet) fastened together into a single barge that was 90 feet long by 28 feet 4 inches wide. Armor plate was installed around its sides for protection of the gun crews. Ammunition storage areas were built on either end and living quarters in the center. This arrangement

[77]

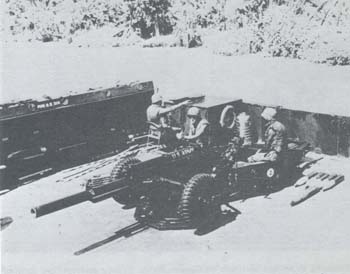

RIVERINE BATTERY POSITION. Six M102 howitzers preparing for an operation

(fire direction center located in center right barge).

[78]

RIVERINE PLATOON MOORED TO CANAL BANK. Living quarters are located in center,

ammunition storage on each end.

provided two areas, one on each side of the living quarters, that could be used to position 105-mm. howitzers. Initially the M101A1 howitzer was used but, as the newer M102 weapon became available in Vietnam, it replaced the older howitzer. A mount for the M102 was made by welding the baseplate of the howitzer to a plate welded to the barge deck. This mount permitted the howitzer to be traversed rapidly a full 6,400 mils.

Three barges and five LCM-8's constituted an average floating riverine battery. Three LCM's were used as push boats, one as the fire direction center and command post and one as the ammunition resupply vessel. Batteries could move along the rivers and canals throughout the delta region; they frequently moved with the assault force to a point just short of the objective area. All the weapons had a direct fire capability, a definite asset in the event of an ambush. Then the howitzers often responded with Beehive rounds, which usually broke up, the ambush in short order.

When a location for the battery was selected, the barges were pushed into position along the riverbank. The preferable position was one where the riverbank was clear of heavy vegetation. This facilitated helicopter resupply, which could then be accomplished on the bank as close as possible to the weapons. Clear banks also

[79]

RIVERINE GUN SECTION IN TRAVELING CONFIGURATION.Note the five Beehive rounds

at left of trails.

provided better security for the battery. The barges normally were placed next to the riverbank opposite the primary target area so that the howitzers would fire away from the shoreline in support of the infantry. This served two purposes: weapons could be fired at the lowest angle possible to clear obstructions on the far bank, and the helipad was not in the likely direction of fire.

The barge was stabilized with grappling hooks, winches, and standoff supports on the bank side of the barge. Mooring lines were secured around the winches and reeled in or out to accommodate tide changes so that the barges would not be caught on either the bank or mudflats at low tide. Equipment to provide directional reference for the weapons-including aiming circle, collimator, and aiming posts-was emplaced on the banks. Accuracy of fires proved to be comparable to that of ground-mounted howitzers.

Without these new developments in riverine artillery, U.S. maneuver force activities in the delta area would have been seriously curtailed or often would have had to take place out of range of friendly field artillery. Instead, the field artillery was able to provide support when and where it was needed.

[80]

page created 13 March 2003