CHAPTER I

Introduction

"Find the enemy!" With these words General Harold K. Johnson, then chief of the staff of the Army, wished me well as I left Washington to become General William C. Westmoreland's assistant chief of staff for intelligence in the Republic of Vietnam. Combat intelligence was not new to me. I knew that finding the enemy was only part of the challenge. Our soldiers would have to fix and fight him. They would need to know enemy strength, capabilities, and vulnerabilities as well as information on the weather and terrain. Such intelligence had to be timely, accurate, adequate, and usable. It was to be my job to build an organization to meet that challenge.

After a series of briefings in Washington and goodbyes in Fort Shafter, Hawaii, I was on my way to serve my country in a third war, albeit in an advisory role, or so I thought. I had just completed two years as Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, U.S. Army, Pacific. During those two years I had traveled from Singapore to Korea visiting United States and allied intelligence activities, including those in South Vietnam. On my last visit there I had presented a study to General Westmoreland and his intelligence staff on my concept for the Army intelligence organization. From Saigon I had gone to Bangkok and presented a similar briefing. I was familiar with the situation in Southeast Asia. I knew that the Viet Cong had better intelligence than we; however, I knew there was much more information available to us if we had the resources and organization to acquire it. The counterinsurgency in Vietnam had unusual intelligence potential in that many enemy military and political organizations were relatively stationary and had assigned areas of operations. We could focus our intelligence efforts on those areas if we knew their locations. During my flight from Honolulu to Saigon I wrote two questions in my notebook: "Where can I normally expect to find the enemy?" and "Where can I normally not expect to find the enemy?" During that flight I wrote scores of answers to each question-every possibility that occurred to me. Later in Saigon we were to refine and

[3]

reduce the answers to a few elements on which timely and adequate information was available. This became the basis for the pattern analysis technique methodology which permitted us to identify and locate enemy base areas. Consequently, we could focus most of our collection efforts on about 20 percent of the country. This step was important in achieving economy of intelligence effort.

I arrived in Saigon on 29 June 1965. My first days in South Vietnam were spent visiting the field and attending briefings. Major General Carl Youngdale, U.S. Marine Corps, was the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, J-2, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV). We were scheduled to have an overlap of about two weeks. On 13 July, the day that Lieutenant General Carroll, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, arrived in Saigon, orders were issued assigning me as J-2. While I was waiting at the airport for General Carroll's plane to arrive, a messenger from MACV headquarters informed me that the Secretary of Defense, Mr. Robert S. McNamara, was to arrive on 16 July. I was scheduled to present the lead-off briefing on intelligence. Upon returning to MACV headquarters with General Carroll I learned that Mr. McNamara wanted to know what resources we needed, not as advisers but to help fight the war. I had been the J-2 for only a few hours as an adviser. Now we were at war. We had much to do in a short time. The challenge before me was taking shape-to develop and supervise a U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, combat intelligence organization.

During the period between my assignment as J-2 and the arrival of Mr. McNamara in Saigon, my staff and I prepared an intelligence briefing and together with the Air Force and Navy staffs developed a list of intelligence units and resources required to support the new combat mission of the MACV commander. Colonel William H. Crosson, the chief of intelligence production, told me that he could not write a valid estimate of enemy capabilities and vulnerabilities because available intelligence was neither timely nor adequate and we were unable to evaluate much of it for accuracy. However, he could write a situation report, and did. The contents of that briefing turned out to be unimportant. Mr. McNamara was interested in learning what we needed in order to do our new job. As I started the briefing he quickly interrupted and asked my views on what was needed to improve intelligence. As a result of that hour-long discussion he asked that a detailed plan be provided to him the next day on my proposals to improve interrogation activities. The briefing pointed up the need for evaluating in-

[4]

MAJOR GENERAL JOSEPH A. MCCHRISTIAN

formation, for separating fact from fiction. It further clarified the challenge: we did not have the means.

While part of my staff prepared the briefing, I worked with others to develop for Mr. McNamara a "shopping list" of intelligence resources required. I learned early that we were starting our planning from scratch. No plans or planning guidance concerning the transition from an advisory organization to a combat organization existed within the J-2 staff. From the Operations Directorate, J-3, staff I learned that they

had done some planning. They had a computer run of a list of troops under consideration. I asked that a listing of all intelligence units and intelligence-related units be extracted; however, the existing computer programming could not do so. The officer in charge of this activity was not knowledgeable concerning intelligence units except for detachments assigned to divisions. It was apparent that the force structure under consideration did not provide adequately for intelligence. This experience revealed the need for computer programs to be designed to extract intelligence and intelligence-related data and for the intelligence staff to participate in force structure planning. No plans were available to J-2. The challenge continued to grow.

For the next several days we received necessary guidance. My staff and I developed the organization and resources that would be required to support our combat mission. That mission was clear: we were to help the South Vietnamese fight a war to defend themselves and at the same time help them to build a nation.

In order for the MACV commander to have adequate intelligence to conduct a defense of South Vietnam we had to consider a geographical area of intelligence interest much larger than that country itself. Not only must we concern ourselves with intelligence on the military, paramilitary, logistical, and political organizations of the enemy within South Vietnam, but we also had to concern ourselves with the location of enemy forces, logistical supplies,

[5]

base areas, sanctuaries, trails, roads, and rivers located within Cambodia and Laos as well as throughout North Vietnam. We had to concern ourselves with the air space extending miles beyond the borders of South Vietnam in order to prevent surprise air attack. We were concerned with patrolling the South China Sea bordering South Vietnam and the extensive waterways within the Mekong Delta which were avenues of approach for logistical support and reinforcements for the enemy. Our future organization and requests for resources had to take into consideration our need to collect, evaluate, and produce intelligence on all of those areas. We needed to know the quantity and quality of war materials being supplied by China and the Soviet Union and her satellites. We needed to be kept informed of any changes of Chinese military forces which could influence the war in South Vietnam. Above all, we needed to know the quantity and quality of manpower the enemy could send to South Vietnam and the will of North Vietnamese leaders and soldiers to persist.

It was apparent to me that a large and sophisticated organization would be required. I fully expected that the United States would be involved in combat and later in military assistance for many years. I was convinced that our military assistance would be required until security permitted political stability. I knew from my experiences in the Greek Communist War and my later service there as the military attaché, as well as from our experiences in Korea, that many years would pass before South Vietnam could defend itself. It takes a long time to identify and eliminate insurgents. The challenge was clear, the opportunity to demonstrate our professionalism at hand. Now was the time to apply the principles we had learned.

Sound decisions depend upon timely, accurate, adequate, and usable information. Wartime decisions carry great responsibility; they affect not only the lives of our fighting men but also the liberty of our people. Decision makers ask questions for which they need answers. In the military, such questions are referred to as essential elements of information (EEI). The number of such important questions should be kept to a minimum. Actually, all decision makers from the Commander in Chief in the White House to the company commander in the field constantly need extensive information concerning the enemy, terrain, and weather. Their desire for information is insatiable. When American soldiers bivouac in a foreign jungle their battalion commanders want to

[6]

know the strength and location of all enemy forces capable of attacking their men during the night, and rightfully so. Very rapidly the list of their questions fills a book, and since the situation is always changing, the answers to this book of questions must be kept up to date. Old information needs to be corrected as additional information on the questioned period of time becomes known. With modern communications a decision maker in Washington is, in terms of time, just as close to the source of information as is the MACV commander. This poses the danger that decisions will be made on information (unevaluated material) and not on intelligence. Information should be evaluated and analyzed before decisions are made on untimely, inaccurate, or inadequate bases.

Intelligence must be timely. Time is precious. Decisions made on untimely intelligence can result in disaster if the situation has changed. Intelligence should get to the person who can do something about it in time for him to do something. Timely reporting requires extensive, dedicated communications in support of intelligence. Timeliness also is dependent upon effectively, written messages. In war, communications are overloaded with questions going back to the originator of information because his initial report was incomplete. Timeliness requires the ability to manipulate data rapidly to assist humans to do the evaluation which only they can do. Computers are a great help, but only that. An automated system of presentation of what a computer "knows" can only reflect a fraction of the data base. The computer data bank must have tremendous storage capacity and programs to permit timely manipulations.

Unless pressure is maintained, promptness will suffer. Each intelligence report should indicate not only distribution made, but when and how each consumer was informed. To insure that highly perishable reports reach commanders promptly, each headquarters should have an individual whose task it is to review the reporting process throughout the intelligence cycle. He must read all reports, not for content but for timeliness. He then must insure that shortcomings are called to the attention of the commanders involved. At J-2, Military Assistance Command, Captain James D. Strachan was responsible for this critical function.

Commanders and staff officers who ask for more information than they need not only delay the receipt of what they need but frequently cannot use what they receive. For example, while I was visiting a division commander he informed me that his division was not receiving requested aerial photography promptly. I immediately looked into his complaint. At that very time, a trailer full of photographs was in his headquarters area. His staff had

[7]

asked for too much. When it arrived they were too pressed for time to examine the large amount they had requested.

Intelligence must be accurate. Commanders must have confidence in it. Adequate facts must be presented for them to accept the intelligence as valid. Sometimes unverified information leads to wishful thinking. The intelligence officer must be conservative and unshakable in letting the facts speak. Rationalization and crystal ball gazing invite disaster. One either knows the facts or one does not. If one does not, the commander must know that fact.

Intelligence must be adequate. It is not enough to know the location and strength of an enemy. Given only that information a commander might avoid combat because he is outnumbered, even though the enemy is out of ammunition and many of his men are sick.

Intelligence must be usable. First of all, it must be at the lowest classification. It should be unclassified if at all possible so that it can be disseminated easily to all who need it. It should be short. It should be easily understood. It should be limited to essentials. It should be easy to handle and reproduce if required.

It is the job of the intelligence officer at all levels to request or direct the acquisition of information; to collate and evaluate it rapidly; and then to disseminate timely, accurate, adequate, and usable military intelligence to all planners and decision makers. This process may take seconds or days. Such intelligence should permit sound decisions concerning combat operations, war plans, and peace plans. Combat operations should encourage, not negate, negotiations for peace.

Since World War II the U.S. government has put aside its previous naive concept of intelligence and has developed our magnificent intelligence team. This team includes the intelligence organizations of most of the executive departments of the U.S. Government All of these organizations have long ago come of age. They are operated by professionals. I knew that we could depend upon willing support from all members of the team. Many of these agencies were represented on the U.S. team in South Vietnam. Directives existed to ensure proper co-ordination of all functions, and it was my experience over many years that co-operation as well as coordination could be expected, but not without strongly held views being expressed by all. Such argument is healthy and necessary for logical coordination However, I was convinced that in time of war the battlefield commander must exercise unity of command in matters of military intelligence. I recommended early that all intelligence within Vietnam be placed under General

[8]

Westmoreland, but this recommendation remained in Headquarters, Military Assistance Command.

Our organization had to develop officers who would keep intelligence "out front," on the initiative. A staff officer who provides intelligence to support operational planning already conceived is actually playing the role of a librarian or a historian. A staff officer who provides the intelligence that causes orders to be issued or plans to be made is an intelligence officer. For example, General Westmoreland had been attending a weekly intelligence briefing at which a sizable number of his staff was present. The briefing was primarily an intelligence situation report. Since we were now at war, such a briefing in my judgment was inadequate. I changed the scope of the weekly briefing to present an estimate of enemy capabilities and vulnerabilities, highlighting changes which had taken place during the week, and at the end of the briefing made my recommendations as J-2 as to actions the commander should take based upon intelligence. At the end of the first briefing of this type presented to General Westmoreland early in August, he asked that the room be cleared of all persons except a few senior officers. He stated that in the future he wanted the same type of briefing and he wanted only his component commanders and the chiefs of his staff sections to attend-that this period would become his strategy session each week.

Another example that took place in August of 1965 was the result of the J-2 staff's controlling a few resources that were moved about the country to collect information in support of the commander's strategy and areas of most concern. Through the use of this resource the location of the 1st Viet Cong Regiment was learned. As soon as the location was known, a telephone call was made to headquarters of the U.S. marines. They were given the information and without delay launched an operation which resulted in the first major encounter between U.S. and Viet Cong forces in Vietnam, Operation STARLIGHT. Operation CEDAR FALLS is another example.

People who have not worked in intelligence normally have no conception of the number of people it takes to perform necessary activities. Without an extensive data base that can be manipulated rapidly, it is very difficult to evaluate information and to identify and ferret out guerrillas and members of the Vietnamese Communist political-military infrastructure. Every scrap of information, every written report, is to the intelligence officer as nickels and dimes are to a banker. It takes a lot of them to make the business profitable. Every piece of information must be accounted for like

[9]

money and confirmed or refuted as genuine or counterfeit. When an intelligence analyst receives an unconfirmed report, he cannot let it go. He must confirm or refute it. From numerous reports the order of battle of the enemy is constructed and updated. The enemy order of battle includes his composition, disposition, strength, training status, morale, tactics, logistics, combat effectiveness, and miscellaneous information such as unit histories, personality files, uniforms, and insignias. These factors describing the capabilities and vulnerabilities of an enemy military force can best be learned by gaining access to enemy military personnel who are knowledgeable on the subject or by gaining access to documents they have written.

The most experienced and sophisticated intelligence officers are selected to be estimators. They use order of battle studies, capability studies, and other information to write valid estimates of how the enemy can adversely affect the accomplishment of our mission as well as state enemy vulnerabilities we can exploit. Statements such as "I think," "I believe," or "I feel" must be avoided. The person hearing or reading an estimate should come to the same conclusion as the estimator because of the validity of the intelligence presented and not because of what the estimator thinks.

I had occasion from time to time to tell new estimators of a lesson I learned some years ago on a visit to the advance base of the Summer Institute of Linguistics located deep in the Amazon jungles of Ecuador. A Cofan Indian and his wife were present in the camp. I asked the Indian, through an interpreter, to give me a lesson on how to use his blowgun. He taught me. I asked if he would not prefer to own a rifle. He replied that he used his blowgun to hunt game, especially wild piglets, for his family. He stated that he could blow a poison dart into each of the piglets as they were feeding and after a while pick all of them up, put them in a bag, and take them home, whereas if he used a rifle the noise of the first shot would frighten the pigs away. Furthermore, he would need money to buy the rifle and ammunition, whereas he was able to make his blowgun and darts from the forest. I told this story from time to time to warn my estimators against using an American yardstick to measure other peoples. Even though a guerrilla may not carry a weapon, he certainly knows how to sharpen and replace a pungi stake or to use a hand grenade made from a beer can. A good intelligence officer must avoid preconceived ideas when it comes to estimating the enemy. In Vietnam, it was necessary to discard temporarily many of the conceptions that our military

[10]

education and experiences had engendered. Our enemy's school was "the bush"- to quote General Giap- and his strategy, tactics, and organization fitted a revised Maoist view of protracted war. For this reason I realized that military intelligence in Vietnam had to adapt if it was to be successful against this enemy.

History records that in time of war the tendency of the U.S. government is to provide the man on the battlefield the resources he needs. The record also reveals repeatedly the sad story of too little too late because we were not prepared. The military also strives to give the commander the resources he needs and furnish him mission-type orders. Because resources seldom are adequate we must retain some under centralized control to be employed in support of the commander's main efforts. We strive for centralized guidance and decentralized operations. History also records that after a war ends resources are greatly reduced, centralized more and more at higher and then higher levels, and given over to civilians to a greater extent. After the Korean War, Army intelligence resources were reduced drastically. In 1965 the resources we needed were not combat ready. Great efforts were made to provide them as quickly as was feasible, but more than two years would be required to receive most of the resources we originally requested. Centralization of scarce resources was continued longer than was desirable.

Even though we were aware that the resources we needed were riot readily available, we asked for them. It was up to higher authority to reduce our requests if they had to do so. At this writing I feel only praise for the wholehearted support we received. Time to organize, equip, train, and deploy the units we needed was the bottleneck.

In making our plans I told my staff to think big. I knew that good intelligence requires a sophisticated and large organization. We were at war; this was no time to grow piecemeal. We needed our best effort as soon as possible.

We needed all the help we could get from our Vietnamese allies. They also needed our help. Experience with other allies had taught me that advising them on how to conduct intelligence is not so effective as is working together. Not only does working together develop competence faster, it also engenders mutual respect and confidence. During my initial call on Colonel Ho Van Loi, J-2, Joint General Staff, Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces, and my counterpart and friend for almost two years, I proposed to him that we engage in combined intelligence activities whenever practicable; he agreed.

[11]

Evolution of the Military Assistance Command Intelligence Organization

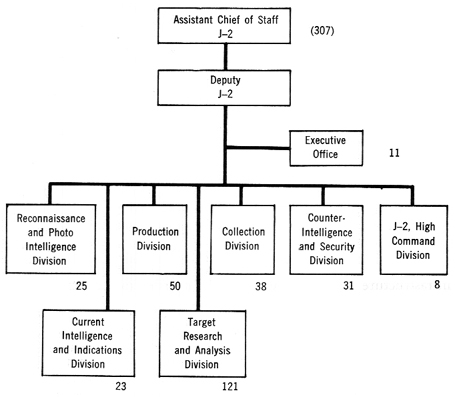

Up to the time the decisions were made to employ U.S. forces and Free World Military Assistance Forces in direct combat operations, the MACV commander's primary means of influencing the conduct and the outcome of the war was through the Military Assistance Program and the advisory effort. Because of limited U.S. participation in combat operations, the scope of Military Assistance Command J-2 activities was also limited. (Chart 1) The J-2 mission at that time was to support and improve the Vietnamese military intelligence effort and to keep the Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam; the Commander in Chief, Pacific; and national intelligence agencies informed on the intelligence situation.

CHART 1- ASSISTANT CHIEF OF STAFF, J-2, STAFF ORGANIZATION, JULY 1965

[12]

Intelligence reports were received from the advisory system, limited bilateral operations with the Vietnamese clandestine collection organization, the 5th U.S. Special Forces Group, unilateral U.S. military collection resources which included special intelligence activities such as airborne radio direction finding, photo and visual reconnaissance, and infrared and side-looking airborne radar reconnaissance. These resources were provided on a very austere basis.

General Westmoreland now became Commanding General, U.S. Army, Vietnam (USARV), as well as MACV commander. He decided to exercise command from MACV headquarters. It then would be my responsibility to support his strategic planning as well as his tactical operations. I would be not only Military Assistance Command J-2 with the responsibility of exercising general staff supervision over all Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps intelligence activities, but in addition I would perform those functions of Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, G-2, U.S. Army, Vietnam, required to support tactical operations of the Army. In this role I assumed operational control of Army-level resources as they arrived. Military Assistance Command J-2 continued to be responsible for advising the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces (RVNAF). The existing organization was not designed to support our new mission and especially this type of war. (Appendix A)

According to existing Army doctrine the intelligence force structure is tailored to the organization it supports and, modified by considerations of the enemy, to terrain, weather, mission, and scheme of operations.

The military problem of defeating the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong main force units on the battlefield was complicated by their utilization of a highly centralized political movement. The Viet Cong infrastructure (VCI) , composed of men, women, and children, operated as the enemy's supply service, intelligence network, and local guerrilla force as well as a shadow government in each village in Vietnam. If victory on the battlefield was to be translated into a just and lasting peace, the infrastructure had to be neutralized. In order to accomplish this sensitive mission we needed a massive data bank and a staff of sophisticated area specialists. This effort eventually supported the political stabilization of the government of Vietnam and the military activity of Free World Military Assistance Forces. We would need a large countrywide counterintelligence effort involved in counter-sabotage, counter-subversion, and counterespionage activities as well as providing support to all units and installations

[13]

concerning security of information, personnel, and surreptitious entry. We would need a large, countrywide area intelligence collection effort in order to provide coverage of enemy areas and organizations to collect information as well as to promote defection of enemy personnel.

Our first step was to identify those resources required to support the U.S. Army, Vietnam. Each separate brigade, each division, and each field force (the name given to a corps) would arrive with its normal military intelligence detachment. In addition, one aviation company (aerial surveillance) and a topographic company were requested to support each field force. The aviation companies were equipped with three models of the OV-1 Mohawk aircraft. The number of each model for each company was determined according to the type of terrain and water in the particular field force area of operations.

We provided for U.S. Military intelligence detachments to be attached to each South Vietnamese division and corps. We developed the manning requirements for the four original combined centers for intelligence, document exploitation, military interrogation, and materiel exploitation. We increased our requirement for advisers in order to provide specialists down to include all district headquarters. For Military Assistance Command we requested a military intelligence group headquarters (a brigade headquarters did not exist) to command a counterintelligence group, an intelligence group, a military intelligence battalion (air reconnaissance support) , and a military intelligence battalion to administer the personnel working in the centers, the advisers, and various support activities. In addition, large numbers of combat troops would be arriving soon, before Military Assistance Command intelligence resources were available. In the interim the war was going on.

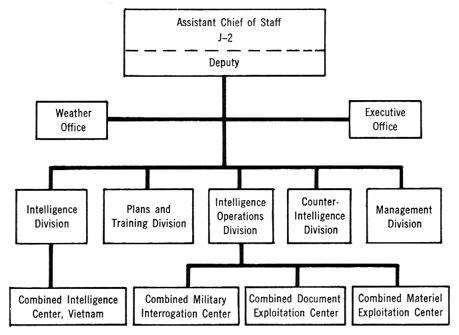

The J-2 staff was a large joint one with many qualified people. I decided to reduce the span of control and at the same time increase the number of functions necessary to perform our new mission adequately. An Air Force weather officer was added to the staff. The old Production Division and the Current Intelligence and Indications Division were combined into the Intelligence Division. The Target Research and Analysis Division, as its name implies, was primarily concerned with locating targets for B-52 bombers. I used it as a nucleus to form the Combined Intelligence Center, Vietnam (CICV). (Chart 2) We needed to increase our data base rapidly and our ability to produce capability studies as well as our ability to select targets not only for the B-52's but for

[14]

CHART 2- J-2 STAFF ORGANIZATION, OCTOBER 1965

all types of U.S. and Vietnamese Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force operations. The organizational concept for the Combined Intelligence Center can best be described by using this matrix:

| Area of Intelligence Interest | |||||||

| Functions | I CTZ Team |

II CTZ Team |

III CTZ Team |

IV CTZ Team |

Cambodia Team |

Laos Team |

North Vietnam Team |

| Order of Battle | |||||||

| Imagery Interpretation | |||||||

| Area Analysis | |||||||

| Targets | |||||||

| Technical Intelligence | |||||||

[15]

Seven teams composed of Vietnamese and Americans were established, one for each of the subareas of intelligence interest. Each team included order of battle, imagery interpretation, area analysis, targets, and technical intelligence specialists or support. The team was our primary data base and production activity. It was placed under the direct supervision of the chief of the Intelligence Division. A plans and training division was created. It was responsible for the preparation of directives and supervision of their execution to ensure proper intelligence training of U.S. And Vietnamese personnel as well as for the preparation of plans involving two or more divisions. The Reconnaissance and Photo Intelligence Division was combined with the Collection Division into the Intelligence Operations Division with many additional combat intelligence functions. The J-2 of the Vietnamese Joint General Staff operated a very small interrogation center in Saigon. I had visited it several times between 1963 and 1965. Colonel Loi and I joined forces and established the Combined Military Interrogation Center (CMIC). The small U.S. effort on documents translation was co-ordinated with the Vietnamese effort to form the Combined Document Exploitation Center (CDEC). When facilities were available these efforts were joined to form the finest documents center I have ever seen. I have always considered the greatest source of information a person who is knowledgeable on the subject and the second greatest source a document containing such information. I took personal interest in all the combined activities, but the Intelligence Center, Interrogation Center, and Document Center received almost daily impetus from me. For this same reorganization I created the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center (CMEC). The Vietnamese placed a few people at this center but operated a facility of their own. Technical intelligence production was done both at the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center and at the Combined Intelligence Center. The Combined Intelligence Center reports were broader 'in scope. The Military Interrogation, Document Exploitation, and Materiel Exploitation Centers were placed under the direct authority of the chief of the Intelligence Operations Division. The Counterintelligence and Security Division was retained and many additional functions were assigned to it. I created a management division to assist me and my staff in handling the large and sophisticated organization now taking shape. (Chart j)

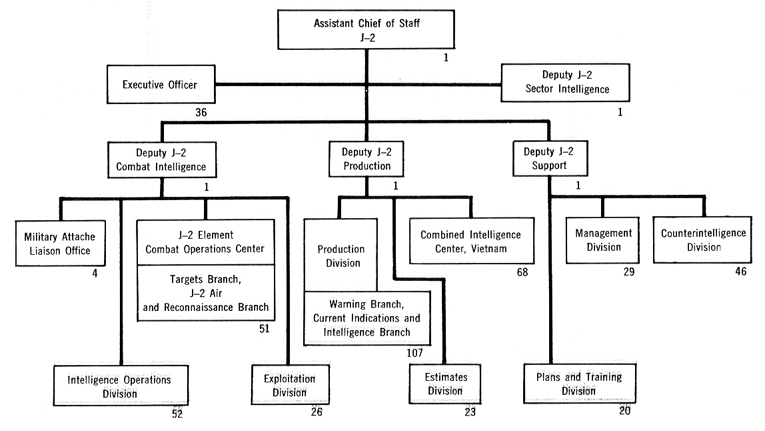

By May 1967 the authorized strength of my staff had grown from 307 to 467. (Appendix B) My request for 166 more people had been forwarded to meet recognized requirements. As my staff

[16]

CHART 3- ASSISTANT CHIEF OF STAFF, J-2, STAFF ORGANIZATION, MAY 1967

[17]

grew in number and functions I kept my span of control small. I insisted that staff memoranda and command directives be written, thoroughly coordinated, and published to insure continuity in our activities. I approved all such memoranda and directives. Once they were approved, my chiefs had full authority to implement them.

Since the war in Vietnam was predominantly concerned with combined efforts to defeat the enemy on the ground, the major impact resultant therefrom was upon the U.S. Army military intelligence organization. (Appendix C)

The U.S. Army intelligence force available in July 1965 included the 704th Intelligence Corps Detachment, Detachment I of the 500th Intelligence Corps Group, and 218 intelligence advisers who were thinly spread among South Vietnamese corps, divisions, sectors, and special zones. The 704th was a small counterintelligence detachment of forty-six men. It was the counterpart organization to the Republic of Vietnam Military Security Service. It had been under my operational control when I was the U.S. Army, Pacific, G-2. However, I had assigned it to Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. It was also engaged in limited counterespionage, counter sabotage, and counter subversion activities. Detachment I of the 500th Intelligence Group had also been under my operational control and was assigned to Military Assistance Command at the same time as the 704th. Detachment I had fifty-six officers and enlisted men. This detachment had a dual role of advising and assisting the South Vietnamese in intelligence collection and engaging in limited collection activities.

Those two detachments were a far cry from what the intelligence force structure should be according to our established doctrine. I knew well such Army doctrine and the capabilities and limitations of all types of U.S. Army intelligence units. As G-2 I had reviewed every U.S. Army, Pacific, contingency plan and had recommended changes in the force structure to support those plans. I had requested a military intelligence battalion to be transferred from the continental United States to Hawaii. This was done. The battalion was reorganized to support the contingency plans better. Part of it was structured to support operations in Vietnam. That detachment was sent in response to my urgent request to assist in establishing the order of battle files for the Combined Intelligence Center. I knew that it would take a year or more for the Department of the Army to activate, train, and deploy to Vietnam new intelligence battalions and groups. However, our organizations were cellular in concept; one could re-

[18]

quest various functional teams to be attached to existing units. Such individual teams could be created rapidly and their arrival could be programmed over a period of months. I requested such teams. This course of action saved time and spread out the buildup so that no one unit or activity had to turn over all its experienced men at one time.

By June 1967 U.S. Army intelligence units under the operational control of Military Assistance Command J-2 had grown in strength from 102 to 2,466, advisers from 218 to 622. (Appendix D) An additional 615 personnel were on request to complete the organization considered essential. Also, the completed staff action of a new table of organization and equipment for a U.S. Army intelligence brigade to be commanded by a brigadier general had been submitted.

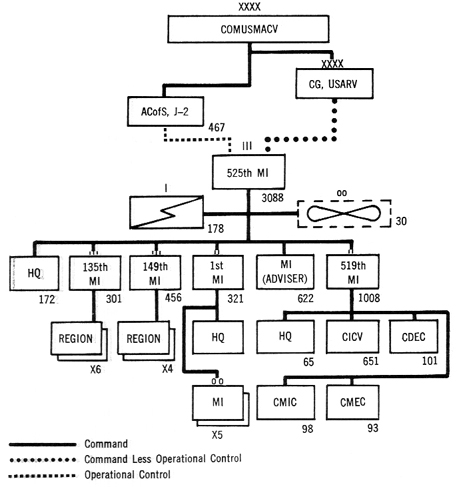

The 525th Military Intelligence Group was under the command of the Commanding General, U.S. Army, Vietnam (General Westmoreland), and under my operational control. The commanding officer of the 525th Military Intelligence Group exercised command over a signal company, an aviation detachment, and the 135th Military Intelligence Group (Counterintelligence) , which absorbed the mission and assets of its predecessor, the 704th Intelligence Corps Detachment. (Chart 4) The 135th was organized into six regions, was dispersed throughout South Vietnam, and was located in most places along with the Vietnamese Military Security Service. The 149th Military Intelligence Group (Collection) absorbed the mission and assets of its predecessor, Detachment I of the 500th Intelligence Group; the 1st Military Intelligence Battalion (Air Reconnaissance Support) , which had the mission of interpreting, reproducing, and delivering Air Force imagery flown in support of ground tactical commanders; and the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion, which provided the personnel and support for the combined centers.

In 1965 U.S. intelligence advisory sections with South Vietnamese corps and divisions were inadequately manned and unable to process the increased flow of intelligence information into U.S. channels; they also had difficulty providing requisite support to Vietnamese corps and division G-2's. To alleviate this problem the U.S. advisory sections with Vietnamese corps and divisions were reorganized as military intelligence detachments with greatly increased manning. In addition, manning levels of special zone and sector advisory teams were increased. The current adviser element reflects an authorized manning level of 621 as compared with the previous level of 218.

[19]

CHART 4- 545TH MILITARY INTELLIGENCE GROUP

We have only taken a glance at the over-all MACV intelligence organization. In order to keep this monograph unclassified I have omitted much. Such information is available in other records for those who are authorized to have it. But I would be remiss if I did not at least mention that special intelligence played a major role. As. Military Assistance Command J-2 1 exercised operational control over much of the effort of special intelligence personnel even though they were shown as being in direct support of the MACV commander. This was done with the full approval of the authorities in Washington.

[20]

page created 8 January 2003