CHAPTER II

Combined Intelligence

The Combined Intelligence Concept

Americans and South Vietnamese were fighting together on the same battlefield against a common enemy. Both of us needed the same intelligence on the enemy, the terrain, and the weather. Each of us had capabilities and limitations affecting our ability to collect and produce the needed intelligence. We Americans would add trained and experienced men, sophisticated equipment, money, professionalism, management techniques, rapid communications, a sense of urgency, and the support of our intelligence team. On the other hand, we had very few linguists who could speak Vietnamese. We were invited to assist the Vietnamese and, as guests of their country, were subject to their sovereignty.

The South Vietnamese were sovereign. They controlled sources of information, real estate, and archives. They had many years of experience in fighting this type of war. They had an insight into the thinking of enemy leaders, they had an understanding and appreciation of enemy tactics and modus operandi, and they knew what information was available in their files and archives and could make it available. They would add continuity to our common activities because they remained when we Americans went home after serving our tours of duty. They spoke the same language as the enemy.

They also had some limitations. They did not have enough trained intelligence officers and specialists. They lacked necessary equipment and money. Together we could be a strong team.

Combined intelligence was not a new concept with me. I had practiced it on much smaller scales before. I had experienced firsthand the value of international co-operation in intelligence operations as General George S. Patton's chief of intelligence in Germany after World War II when thousands of refugees had to be screened, in Greece in 1949-1950 during the successful counterinsurgency there, and in various other countries where U.S. intelligence worked in concert with local intelligence agencies.

[21]

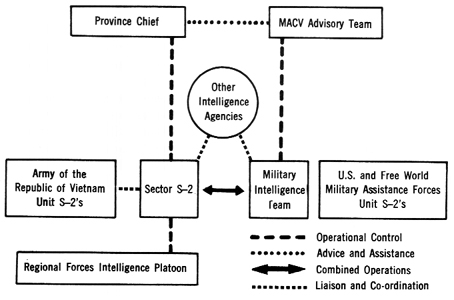

During my initial call on Colonel Loi, I discussed our capabilities and limitation and proposed that we create a combined intelligence system with activities at all levels of command. He enthusiastically agreed. The concept envisioned the United States forces working not merely in an advisory role, but side by side with the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces as equals in a partnership. In the system we would establish centers throughout the country for interrogation of prisoners and Hoi Chanhs and for exploitation of captured documents and materiel as well as a center where all information would be sent for collation, analysis, evaluation, and processing into intelligence in support of U.S. and South Vietnam forces. Combined training would be conducted to familiarize U.S. And South Vietnamese personnel with each other's intelligence procedures and techniques; there would be an exchange of Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and U.S. military intelligence detachments at all levels down to separate brigade.

The combined concept was founded in mutual need, trust, and understanding. The Vietnamese had to know that the United States was working openly with them. In turn, I had to dispel the criticism some Americans voiced implying apathy on the part of our counterparts. Unlike the U.S. advisers who would be in the country only one year, the Vietnamese were permanently committed in their homeland. We were obligated to work a seven-day week; we had, essentially, nothing else to do. The Vietnamese had been under the pressure of fighting a war for years. They had families to rear and care for. They could not match our schedules or initial energy year after year under pressure, but they were on the job around the clock if needed.

Attention to detail in every regard was necessary for success of the combined concept. The combined centers were to have co-directors (U.S. And Vietnamese) occupying adjoining offices. Daily visits and command supervision at all levels were in order. A positive approach was taken by all concerned. Before U.S. personnel were assigned to any of the combined centers, an orientation program was mandatory and we stressed continual reeducation. Daily fifteen-minute language classes, conducted for Americans with the objective of improving our capability, served as evidence of our sincerity to assist the Republic of Vietnam. In addition, all briefings and charts were bilingual. As sophisticated equipment arrived, the Vietnamese were taught to operate and maintain it, and eventually the computers were programmed bilingually to include diacritical marks. Vietnamese and Americans

[22]

performed the same tasks together, be it reviewing an agent report or a computer printout or answering a request from a combat unit. The combined approach offered a continuity of effort and direction as well as an opportunity to learn from the Vietnamese while they learned from us.

As the U.S. role increased, as our intelligence requirements grew in complexity, the need for definitive political and diplomatic agreements began to surface. The sovereignty of the government of Vietnam had to be protected by the military intelligence community. We found that technically we lacked the authority to accomplish many of our intelligence functions. How were we to handle prisoners? What disposition was to be made of captured documents and materiel? This was not a declared war. We were there not as a conquering army or liberation force; we were in South Vietnam to help the people win a war and build a nation. Their sovereignty was inviolate.

Consequently, much work had to be done to prepare necessary agreements, not only between Military Assistance Command and the government of Vietnam but including all the Free World forces. An important lesson to be learned from our experiences in Vietnam is that we should have within the intelligence community samples of agreements that might be necessary on such activities as the handling of prisoners of war, the release of classified information, and combined intelligence activities. The formal agreements were made not solely to assign specific responsibilities; they were a means of providing continuity and increasing efficiency. They also contained manning and staffing requirements and explained command and control channels. A separate agreement was negotiated for each of the combined activities. While all were similar as to administrative procedures, each had distinct aspects:

In addition to complying with the Geneva Convention, each signatory of the agreement establishing the Combined Military Interrogation Center agreed to turn over to the center as soon as possible any significant or important prisoner. As for the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center, priority on captured materiel was assigned to the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces. Any time a new piece of enemy materiel was captured, the first model was released to the South Vietnamese after exploitation for display in their museum. The second model went to the United States for further tests and evaluation. Subsequent pieces were returned to the capturing unit, or if they were of a type used by our allies they could be returned to supply channels. The agreement for the Combined Document Exploitation Center stipulated that the

[23]

government of Vietnam retain ownership of all captured documents, currency, and publications of all types.

Since the United States provided a large portion of the financial support of all the Free World forces, it was only to be expected that some formal arrangements for accountability of funds be established. In the intelligence field, the MACV J-2 agreed to provide contingency funds but retained authority to approve all projects for which funds were requested and to monitor such projects and receive reports that resulted from them. Recipients would be required to maintain detailed fiscal records and submit them for audit by a J-2 representative.

Another important agreement concerned the employment of South Vietnamese Army intelligence detachments with U.S. units. The significant aspects were the organization of the detachments, command relationships, logistical support, and administration.

The Military Intelligence Detachment Exchange Program

The Military Intelligence Detachment Exchange Program was implemented to improve combat intelligence in U.S., South Vietnamese, and Free World Military Assistance Forces tactical units. Regardless of the language barrier, the attachment of U.S. detachments to South Vietnamese divisions provided the Vietnamese commanders with special skills and technical expertise not normally available and, as a bonus, afforded an excellent channel through which pertinent information could be forwarded to the J-2, Military Assistance Command. Of particular interest to this report, however, are the benefits derived from the attachment of South Vietnamese detachments to U.S. corps-level headquarters, divisions, and separate brigades.

The program began officially in January 1966 with the signing of an agreement by the United States and Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces. (Later both the Korean and Australian forces negotiated similar agreements.) To facilitate implementation and promote compatibility, the South Vietnamese military intelligence detachments were to be organized in accordance with the table of organization and equipment of a U.S. Military intelligence detachment organic to airborne and Marine brigades. (Appendix E). At full strength such a detachment consists of eight officers, eighteen noncommissioned officers, and four enlisted men comprising a headquarters, prisoner of war interrogation (IPW) section, order of battle (OB) section, imagery interpretation (II) section, and document analysis section. Even though the Vietnamese intelligence school in Cho Lon was operating at full capacity in order

[24]

to provide intelligence specialists, the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces was short of trained intelligence personnel, and reduced strength detachments had to be formed and deployed to avoid excessive delays in initiating the program. Particular emphasis was placed on obtaining additional interrogators and documents analysts. As detachments became operational, assignments were made in accordance with J-2 priorities.

Upon joining a U.S. unit, the South Vietnamese detachment normally was integrated with the organic intelligence detachment, complementing it with skilled intelligence specialists who were proficient linguists knowledgeable in local dialects, customs, and habits. Their ability to analyze captured documents or interrogate prisoners on the spot enabled commanders immediately to exploit information of tactical significance. As the Vietnamese became more proficient, they enhanced the timeliness of local intelligence by rapidly culling the unimportant and identifying those that merited further processing. Indeed, units without Vietnamese support often contributed to the overload of the exploitation system by forwarding volumes of meaningless documents.

Continuity proved to be an enduring benefit made possible by having Vietnamese elements with the U.S. Units The rapid turnover of U.S. soldiers hindered the development and maintenance of intimate familiarity with the enemy and the local area. The permanence of the Vietnamese detachment greatly alleviated the problem. This benefit carried over into civil affairs and relations with local agencies where in several instances the Vietnamese personnel played a leading role in establishing rapport with the Regional Forces and Popular Forces, National Police, sector officials, and other government authorities.

The exchange program was the subject of some controversy, and not all our intelligence officers considered it either worthwhile or desirable. Difficulties arose because of language barriers, the difference in customs and habits, and the relatively short tenure of U.S. Intelligence personnel. Over-all, the program justified its existence, though it would be inaccurate to say that every G-2 was satisfied with his Vietnamese detachment. Most G-2's who conscientiously integrated the Vietnamese unit into their intelligence apparatus enjoyed outstanding success in accomplishing missions and satisfying requirements levied by their commanders.

By May 1967, and with the exception of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, 196th and 199th Light Infantry Brigades, and the Republic of Korea Marine Brigade, all U.S. And Free World forces had Vietnamese military intelligence units assigned.

[25]

Vietnamese units were being trained for the other organizations and were assigned later in the year.

The Combined Interrogation System

Establishment of an effective program for the interrogation of enemy prisoners and Hoi Chanhs was a high priority objective. At a briefing for Secretary McNamara in July of 1965, I presented my plan calling for the construction of military interrogation centers at each division, sector, and corps, along with a national center at Saigon. This plan was co-ordinated with embassy representatives, who agreed, with the exception of interrogation centers at sector level. They considered these centers more closely related to the police effort than to the military and consequently thought they should be constructed by civil authority. I accepted this proposal with the understanding that facilities within the sector centers would be available for use by military interrogators. An embassy representative accompanied me to Secretary McNamara's briefing and acknowledged this commitment. The secretary approved the plan and directed that it be implemented.

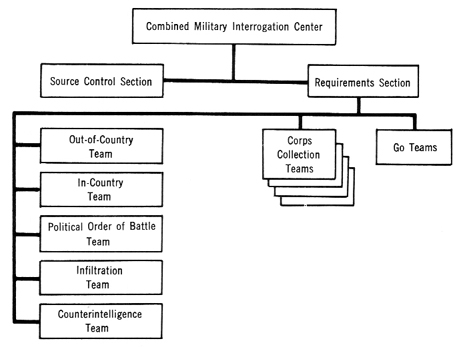

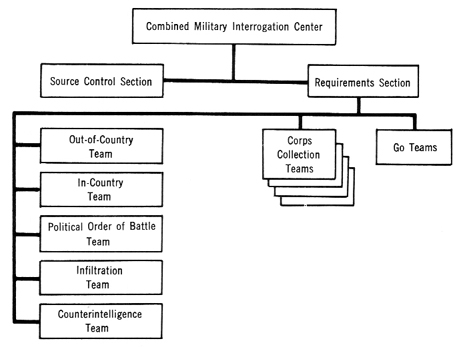

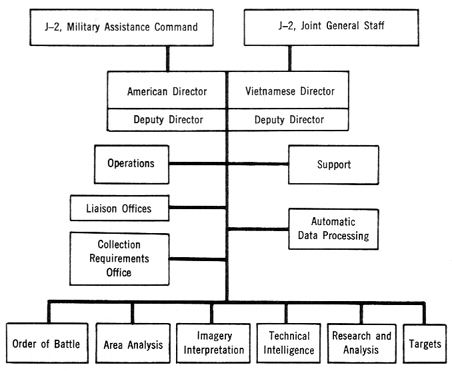

The agreement for a combined intelligence exploitation system provided for interrogation of captives and returnees. In consonance with its terms, the Combined Military Interrogation Center (CHIC) was established in Saigon and became the focal point of tactical and strategic exploitation of selected human sources. (Chart 5) As with the other exploitation programs, Americans and Vietnamese working together in a spirit of cooperation and mutual support carried out the combined interrogation activities. The success we achieved with this program is a tribute to the outstanding performance of duty of Major Lawrence Sutton, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick A. Pieper, and Captain Lam Van Nghia, who were instrumental in making the center operational. The system promoted maximum utilization of available resources and facilitated the exchange of sources and interrogation reports, allowing cross-servicing of requirements. Perhaps the greatest benefits accrued to the United States since a persistent shortage of trained, Vietnamese-speaking interrogators had seriously curtailed American efforts to exploit human sources. As a result of the combined concept, the over-all interrogation effort profited as the native fluence of the South Vietnamese was complemented by U.S. technical expertise. Many of our highly qualified interrogators learned Vietnamese at the language school in Monterey. Sergeant Sedgewick Tourison deserves special mention. His professionalism and dedication to duty were consistently outstanding. He proved to

[26]

CHART 5-ORGANIZATION, COMBINED MILITARY INTERROGATION CENTER, MAY 1967

be invaluable in key interrogations on numerous occasions, an important example of which was his detailed interrogation of nineteen Vietnamese naval personnel picked up in the Gulf of Tonkin after their patrol craft was sunk. As of 15 May 1966, the Combined Military Interrogation Center had a total of ten U.S. language-qualified interrogators. I was also fortunate to have an excellent linguist in my special assistant, Captain James D. Strachan, who was the honor graduate of the 1964 Vietnamese language course at the Defense Language Institute, West Coast Branch.

The Combined Military Interrogation Center personnel complement consisted of an Army of the Republic of Vietnam and a U.S. element, both headed by directors with equal authority in the operation of the center. Operational control of the center emanated from both J-2, Military Assistance Command, and J-2, Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces Joint General Staff. (Appendix F) We organized the center along functional lines, simplifying the

[27]

definition of responsibilities and expediting processing of captives and detainees.

A source control section was created to facilitate selection of sources to be brought to Saigon. It reviewed preliminary interrogation reports submitted by lower echelons in order to identify knowledgeable sources. This evaluation went to the Requirements Branch which selected the interrogatees to be evacuated to the Combined Military Interrogation Center. During the first four months of 1967 the center distributed 675 interrogation reports and 1,068 intelligence information reports. Each interrogation report was reproduced in 350 copies and sent to 92 different addresses worldwide.

The Requirements Branch was the nerve center of combined interrogation. Based on specific intelligence collection requirements generated by units throughout the country and validated by J-2, Military Assistance Command, the branch matched these requirements to knowledgeable sources. They briefed the appropriate requirements team on what they knew concerning the source, and finally they insured that all requirements had been satisfied before authorizing termination of an interrogation. The Requirements Branch supervised five requirements teams, each specializing in particular intelligence requirements. They knew what we knew and they knew what we needed to know. One team sought information about the enemy order of battle outside Vietnam. Another was concerned with order of battle within the country. Enemy tactics, weapons, equipment, psychological operations, and political order of battle (the enemy infrastructure) fell within the purview of a third team. A fourth team focused on counterintelligence: sabotage, espionage, and subversion directed against allied facilities or men. The fifth team concentrated on enemy infiltration. The members of the requirements teams briefed the interrogators and furnished the questions to be asked.

Interrogation reports published by the Combined Military Interrogation Center received wide distribution. Since sources interrogated in Saigon normally already had been exploited for any "hot" information before reaching the center, these reports seldom contained perishable intelligence. If the need arose, however, spot reports of immediate interest were transmitted electrically. A daily summary advised the intelligence community (including Washington) of the type of information obtained from the sources on hand. Knowledgeability briefs, too, were dispatched to interested parties announcing the availability of each source and his area of expertise.

[28]

The Combined Military Interrogation Center stationed collection teams with each corps and throughout South Vietnam. "Go" teams composed of U.S. and South Vietnamese interrogators were always ready to be dispatched from Saigon to support combat units when interrogation requirements exceeded local capabilities. These teams were especially valuable during sweep operations that resulted in multitudes of detainees who had to be given at least a cursory check in order to detect exploitable sources.

Evacuation of prisoners flowed normally from the capturing unit to the brigade or division detention area where tactical interrogation could be accomplished. Subsequent transferrals to the local Vietnamese interrogation facility or evacuations to the U.S. corps combined center depended on the captive's knowledge. This factor also influenced further channeling to the Combined Military Interrogation Center or the government's national interrogation center (if he had nonmilitary information) for thorough interrogation. After completing the interrogation process, the captive was placed in a detention center. Expeditious processing was stressed at all levels of command, and each echelon was encouraged to limit interrogations to information in satisfaction of local requirements. Seven days was the maximum time any element below the Combined Military Interrogation Center was authorized to detain a captive.

A preliminary interrogation report reflecting highlights of the field interrogation was submitted through channels to the combined center via J-2, Military Assistance Command. Reports of any subsequent interrogations also were distributed to higher and adjacent commands. They included pertinent biographic data, the circumstances of capture, areas of special knowledge, and an assessment by the interrogation team of the source's physical condition, intelligence, and co-operativeness.

Returnees (ralliers or Hoi Chanhs) usually were transferred by the acquiring unit to the nearest Chieu Hoi center or government agency. If the returnee had information of intelligence value, he might be evacuated for interrogation through the same channels as captives but was afforded special treatment to demonstrate the benevolence of the United States and the government of Vietnam and to elicit his co-operation. Within the combined centers, ralliers had separate dormitories and mess halls and were placed under very few restrictions. As soon as his interrogation was completed, the returnee was housed in the Chieu Hoi center of his choice. If a returnee was questioned within a Chieu Hoi center, we ordinarily worked openly in a lounge or mess hall and we emphasized winning

[29]

RETURNEES WERE SEPARATED FROM PRISONERS and given greater freedom while being interrogated.

his cooperation In the case of very important captives or returnees, the system was flexible enough to permit expeditious processing, enabling the source to reach an appropriate level, usually the combined center, for timely interrogation.

One such source, Le Xuan Chuyen, chief of operations of the Viet Cong 5th Division, defected as a result of one of our counterintelligence operations and was given a private office at the Combined Military Interrogation Center. Chuyen came under government control in Binh Thuan Province, and in order to get him to Saigon as soon as possible, Captain Strachan coordinated a U-21 aircraft en route with an empty seat. The "red carpet" treatment was given to Chuyen, whose seat on the plane was opposite that of Lieutenant General John A. Heintges, Deputy Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

During my tour as J-2, Military Assistance Command, I insisted that the interrogation program comply rigidly with the provisions of the Geneva Convention. Abuse by individual Vietnamese, however, did occur. The French and mandarin heritage of brutality died hard, especially in the field, despite the efforts of more enlightened American and Vietnamese officers. Further, many

[30]

RETURNEES WERE NORMALLY INTERROGATED IN AN INFORMAL SETTING, in this case a mess tent.

members of the Viet Cong infrastructure were not classified as prisoners of war and were interrogated by the National Police, a civil organization which was tasked with the neutralization of antigovernment sentiment. At the Combined Military Interrogation Center, the requirements of the Geneva Convention were observed and prisoners were treated humanely. Vietnamese interrogators exhibited commendable finesse in questioning prisoners. By virtue of their common language and national heritage, they were successful in establishing rapport with prisoners who only hours before may have been enemy soldiers.

I designed the Combined Military Interrogation Center building to include a combined classroom facility. Vietnamese and U.S. soldiers from all over Vietnam here received, interrogation training which included the provisions of the Geneva Convention. Any form of maltreatment of sources was strictly taboo.

The Interrogation Center maintained close liaison with the other combined centers. The analyst in the Combined Intelligence Center needed to keep the appropriate requirements teams at the Interrogation Center informed on his intelligence needs. He, in turn, needed to be kept informed on the potential of available

[31]

A QUALIFIED U.S. INTERROGATOR WHO CANNOT SPEAR VIETNAMESE questions a source with the help of a Vietnamese WAC interpreter.

sources. Each member of the combined intelligence system needed to know how he could help other centers and how they could help him.

Combined Document Exploitation

Before 1 October 1965, document exploitation was primarily a function of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces. Our participation was limited to an advisory role since we had only a small translation pool of approximately eight U.S. military personnel and thirty Vietnamese civilians. The main weakness in the effort was the absence of documents to be translated. Vietnamese soldiers had not been imbued with the need to locate and evacuate enemy documents. When they did send some to their headquarters, the documents were kept and not forwarded. Documents are an excellent source of intelligence, second only to a knowledgeable person. I had had much experience in World War II, and later, concerning acquisition and exploitation of documents. I had visited these activities throughout South Vietnam over two years and knew the potential. I had recommended to my predecessors the enlargement of this important source of information. Now we had to have it.

[32]

INTERROGATORS RECEIVED TRAINING by sitting in on interrogations and by conducting interrogations under the tutelage of qualified personnel.

I sent for Lieutenant Colonel Henry Ajima. He and I had worked together, and I considered him the most competent officer in the Army on the subject. During a period of temporary duty with me in Saigon we made detailed plans, including the written job description for every civilian employee who was to be hired. Colonel Ajima left with the understanding that as soon as the facility which he and I designed was ready he would join my staff to be a codirector of the new Combined Document Exploitation Center.

In the meantime we started hiring people. We wrote the necessary directives. We stimulated the flow of documents. And I requested the Defense Intelligence Agency to train a team of specialists on the intelligence subject code and assign them to me. This was done.

I also requested that an FMA document storage and retrieval package along with a civilian technician and a civilian maintenance man be delivered as soon as possible. They arrived in a short time and set up trial operations in one of my offices. When the building was ready Colonel Ajima arrived and we moved in. We were in business. This center turned out to be of unsurpassed value.

The Combined Document Exploitation Center opened at

[33]

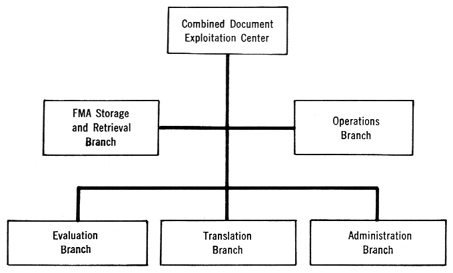

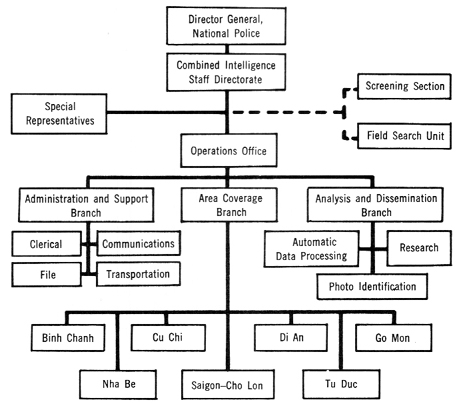

its location near the Tan Son Nhut air base on 24 October 1966, implementing the agreement between the Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and the chief of the joint General Staff for the conduct of combined intelligence activities. (Chart 6) The center was assigned the mission of supporting allied military operations by receiving and exploiting captured enemy documents, co-ordinating the over-all joint document exploitation effort, and providing field support teams, translation, and document storage and retrieval services. The center had five major functional elements with an authorized strength of over three hundred U.S. And South Vietnamese military personnel as well as Vietnamese civilians.

From July 1966 to May 1967 the center received well in excess of three million pages of enemy documents. Approximately one third of this input was the result of Operation CEDAR FALLS in January 1967, followed by Operation JUNCTION CITY in February. These two operations accounted for nearly one million pages of enemy documents processed by the center. Of this total input, approximately 10 percent was summarized or fully translated into English for distribution to interested agencies. Experience proves that of any batch of documents acquired on the battlefield, at least 10 percent contain information of definite intelligence value.

CHART 6- ORGANIZATION, COMBINED DOCUMENT EXPLOITATION CENTER, MAY 1967

[34]

INNER COMPOUND AT CMIC, where prisoners were detained and interrogated. Each room had a dutch door which was left open during interrogations to discourage mistreatment of prisoners.

The document exploitation process began at the center immediately upon receipt of documents from capturing units. Generally, documents arrived at the center neatly packaged and tagged with details of the capture including date, place, circumstances, and identity of the capturing unit. During major military operations, however, documents were delivered to the center in every conceivable type of container-bags, boxes, cans, quarter-ton trailers and trucks. Many tactical units delivered documents within hours after capture. During Operations CEDAR FALLS and JUNCTION CITY, documents were received from tactical units as quickly as eight to ten hours after capture, with exploitation being completed within twenty-four hours after capture. If tactical units were unable to deliver documents to the center, then fully equipped combined field teams from the center joined the units to help exploit the documents on the spot.

Initially, documents were carefully screened by highly qualified Vietnamese civilians assigned to the Evaluation Branch. Many of these examiners were retired or demobilized military personnel,

[35]

such as Captain Sang, who served as the deputy director of the Vietnamese element of the center until his demobilization in April 1967, or Captain Loi, a former member of the G-2 Section, Vietnamese IV Corps. During the screening, in which the Vietnamese element also participated, the documents were divided into five distinct categories to establish priorities for exploitation as well as disposition:

Category Alpha, or Type A, documents required immediate processing, with results being returned to tactical units without delay in the form of a spot report. An example would be an enemy operation plan for an ambush of a friendly element. In these instances the urgency of the information dictated the use of the "hot line" telephone system available to the center for notification to the unit concerned.

The Type Bravo documents contained information of strategic intelligence value such as Viet Cong certificates of commendation, which contained names of Viet Cong as well as unit identification, or a notebook containing information as to the composition, strength, or disposition of an enemy unit. Most of the documents processed through the center were of the B category. All such documents were quickly summarized into English and clearly identified with a permanent document log number.

The Type Charlie documents were those considered to be of marginal intelligence value, such as an enemy-produced sketch map of Africa. These documents were passed to the South Vietnamese element of the center without further processing.

The Type Delta documents were generally propaganda materials such as an English-language document encouraging U.S. troops to write to such organizations as the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) . This category of documents also included currencies of all types, such as North Vietnamese currency. The propaganda materials were forwarded to the appropriate psychological warfare agencies, while the currency was forwarded to the appropriate custodian.

The Type Echo documents contained cryptographic or other information on the enemy communications system, such as the training manual on wire communications. These were passed to the appropriate signal intelligence agency without further processing at the center.

The Alpha and Bravo documents were then routed to another group of highly qualified document specialists who prepared the actual summaries of each document. Those documents which contained detailed information beyond the scope of a summary or

[36]

CDEC TRANSLATORS

gist translation were so identified and routed to the Translation Branch for full translation. All such documents had already been summarized, so the time element for full translation was not always a critical factor.

The translators represented the largest single group of highly trained language specialists in Vietnam. Most of them, having acquired a basic knowledge of English in their normal academic training, underwent specialized translator training with the civilian personnel office. Upon employment at the Combined Document Exploitation Center, these translators were placed on a six-month on-the-job training cycle. Such training was emphasized because the Viet Cong, with their propensity for cover names, codes, and jargon, had developed a separate language, unintelligible to the average Vietnamese. From necessity we developed reference books such as the Dictionary of Viet Cong Terminology required by our translators. Upon completion of the summary or full translation process, documents were immediately forwarded to the Typing Section of the Administrative Branch. Because our typists did not speak, read, or write English, their work had to be closely checked by a group of U.S. Military personnel. Then, all documents were routed into the Reproduction Section. During 1966

[37]

it was a big day when 100 pounds of reports were printed. By early 1967 the daily volume averaged 1,400 pounds of reports, with every indication of greater volume in the future.

To permit faster response to intelligence requirements the center had the most up-to-date equipment, such as the multilith platemaster, which photographs and develops masters to be used on the multilith press, which prints at the rate of 6,000 pages per hour; and the collator-stitcher, which automatically assemblies and staples each report. Reports then went into the distribution point for Army Post Office or courier delivery to interested agencies. Average time for each report from beginning to end was roughly six hours.

As soon as the master copy of a document summary or full translation entered the Reproduction Section, the original Viet Cong documents and the English translation were diverted to the FMA Document Storage and Retrieval Branch. The first step was the detailed indexing of each report by the team of highly trained U.S. intelligence analysts. The indexing system used was the intelligence subject code. Here, every name, unit identification, place name, and document or report number that appeared in the report was recorded for retrieval purposes. The next step was keypunching the index data on the flexowriters. This equipment produced an index card associated with the FMA system as well as an index tape. Then the index card, the English translation, and the original document were recorded on 35-mm. microfilm. For retrieval, the highly sensitive but dependable FMA equipment was used: A question is entered into the machine by use of a request card; the card is inserted into the retrieval unit and when the search button is pressed, the machine begins an electronic search at the rate of 6,400 pages per minute; each time a frame appears that answers the question, the machine projects an 8x10-inch image of that report on a screen. The machine can make hard copies in five seconds. Document reports, interrogation reports, agent reports, and Military Assistance Command intelligence summaries were indexed and entered into the system. To permit greater access to this data base, the system also provided answers to queries in the form of microfilm strips and 16-mm. film which could be used by the requester on film reader printers which were made available to all headquarters.

To provide efficient use of the data base, this system was interfaced with the IBM 1401 computer located at the Combined Intelligence Center. The link was provided by the IBM 047 converter which converted the document indexing data from the

[38]

index tape into IBM card format. These IBM cards, which contained all indexing data, were then programmed into the 1401 computer. This provided the intelligence producers with complete data regarding the availability of information on a specific unit or subject.

At this point the original documents, which were the legal property of the Republic of Vietnam, were passed to the Vietnamese document archives which was also located in the combined facility. Here, files of selected Viet Cong documents dating back to January 1962 were available for perusal by the intelligence community.

To assist national intelligence agencies and staff sections, the center's complete 35-mm. microfilm data base was furnished Pacific Command and the Defense Intelligence Agency and was updated continually. Personnel of the center periodically visited major headquarters in Vietnam to photograph their intelligence files and reduce them to 16-mm. microfilm cartridge format for permanent retention. Since captured enemy documents legally remained Vietnamese property, the Vietnamese complement at the Combined Document Exploitation Center comprised the national archives for such material.

"Go" teams from the center were available to aid in screening large amounts of documents captured or uncovered during combat operations, but often there was just too much material for the teams to translate. Before teams were dispatched we encouraged sending such materials by special courier to the center, where document exploitation was much more efficient. Most commands followed this procedure.

In the tactical units, personnel in the interrogation sections processed captured documents in addition to conducting prisoner interrogations and administrative functions. Documents obtained during combat operations usually were forwarded directly to brigade where a small U.S. And Vietnamese team screened them for information of immediate tactical value and issued spot reports on critical or perishable items. On some operations an interrogation team accompanied battalion-size units, and the initial screening and readouts were done at that level. The documents then were passed to the division or separate brigade authorities for more detailed processing. At division level, document processing was more thorough; however, emphasis was placed on getting the documents back to the combined center as quickly as possible.

Document evacuation policies were not uniform; human factors combined with physical elements resulted in procedural variances.

[39]

Some units, such as the 25th Infantry Division in Cu Chi, were close enough to Saigon to send daily couriers to the center. The 1st Air Cavalry Division and the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment often used helicopters for quick transfer from the capturing unit to higher headquarters. It was preferred that the tactical units send documents to the center for full translation rather than tie up their organic interpreters and translators. Experience showed that the Combined Document Exploitation Center could, by far, provide the most rapid readouts, summaries, and full or extract translations of significant documents. When we discovered that some units were delaying transfer of certain documents until they could complete local exploitation, we procured duplicating machines so that units could copy documents they wished to retain and send the originals back to the center. This simple measure permitted significant improvements in our document exploitation system.

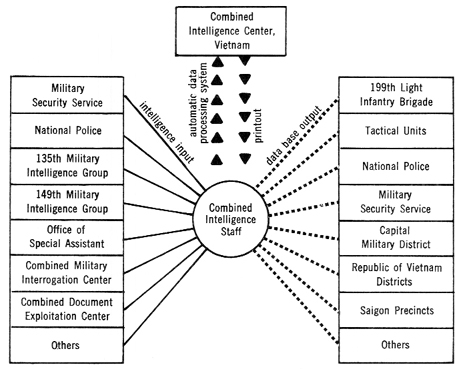

The objective of the Combined Document Exploitation Center, as well as the Combined Military Interrogation Center and the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center, was to provide the data base essential to intelligence production organizations such as the Combined Intelligence Center.

Combined Materiel Exploitation

In August 1965, the Military Assistance Command technical intelligence capability was limited. The collection and examination of captured materiel was done as little more than additional duty as time and work load permitted. From this austere beginning a sophisticated, efficient materiel exploitation program evolved. We designed a suitable organization, requisitioned the necessary specialists, and prepared the requisite MACV directives to establish the materiel exploitation system based upon a formal agreement between Military Assistance Command and Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces. Qualified technical intelligence personnel were few. Again we taught special classes and conducted on-the-job training for fillers while the few experienced, qualified specialists who had been developed in the country sought to get on with the war. Majors Donald D. Rhode and John C. Baker and Vietnamese Army Major Van Lam played key roles in the development of the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center, and through their efforts command technical intelligence grew rapidly and efficiently.

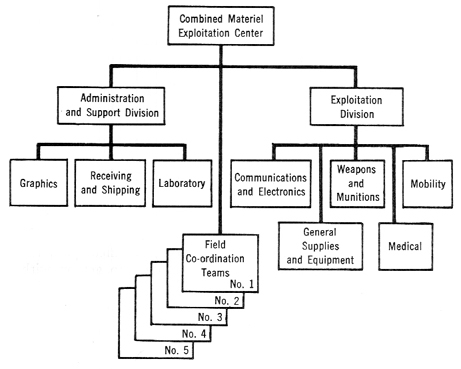

The Combined Materiel Exploitation Center was charged with collecting and exploiting captured materiel of all types, and this entailed examination, identification, analysis, evaluation of the

[40]

items, and dissemination of the intelligence obtained. We needed to determine the characteristics, capabilities, and limitations of enemy materiel and equipment so that adequate countermeasures could be devised. The center tailored its organization for the Vietnam environment in an effort to realize maximum exploitation. (Chart 7) The Graphics Section provided illustrator and photographic support; the Laboratory performed chemical analysis to determine the composition of unidentified substances; Receiving and Shipping received materiel from capturing units and prepared selected items for shipment to the United States; the Communications-Electronics Section exploited all signal equipment, including electronic and photography items; the Mobility Section evaluated and analyzed enemy mines, booby traps, engineer items, transportation equipment, construction, and barrier materials; the Weapons and Munitions Section analyzed fragments to determine the type of ammunition employed; the Medical Section evaluated enemy medical supplies, equipment, medical capabilities, and noneffective rates due to medical causes among enemy units; and the General

CHART 7- ORGANIZATION, COMBINED MATERIEL EXPLOITATION CENTER

[41]

Supply and Equipment Section evaluated and analyzed enemy clothing, individual equipment, rations, petroleum products, and chemical, bacteriological, and radiological equipment.

Specific intelligence collection requirements listing items of enemy materiel for which the intelligence community had a need were prepared by the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center and published by J-2, Military Assistance Command, to provide collection guidance to field commanders. When captured or otherwise obtained, items of command interest were reported expeditiously through intelligence channels to J-2, Military Assistance Command, while the materiel itself was tagged by the capturing unit and evacuated to the center for full-scale exploitation. Items of captured materiel determined to be of immediate tactical importance were spot reported through channels and the center dispatched a "go" team to effect immediate exploitation. The lack of experienced technical intelligence personnel hindered exploitation by U.S. units below division and separate brigade. The unit's primary responsibility concerned the recovery and evacuation of materiel from the capture site to the nearest maintenance collecting point, except for food and medical supplies which were handled separately and explosive items that were evacuated through ammunition supply channels. When evacuation was impossible, either because of the tactical situation or the size of the item, all pertinent data were recorded and, along with photographs or sketches, forwarded to the center for analysis and examination.

Exploitation of captured materiel at division and separate brigade level was limited to a determination of the immediate tactical significance, and the materiel was then evacuated to the combined center. The prompt evacuation of significant items of captured materiel was stressed.

Captured materiel was channeled to collecting points located within each area support command of the corps tactical zones. Such movements were performed by the maintenance support organizations of the capturing unit or by support organizations providing logistical services within the corps. The materiel normally remained at each echelon until it was examined by technical intelligence personnel. Except for authorized war trophies, captured materiel could not be removed from Military Assistance Command or otherwise disposed of until released by technical intelligence personnel of the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center.

Screening and preliminary field exploitation of captured materiel was done by field co-ordination teams that normally operated

[42]

MATERIEL OF INTEREST TO THE GENERAL SUPPLY AND EQUIPMENT SECTION OF CMEC was screened in detail.

in the corps and division support areas. When required, they also provided direct assistance to capturing units. Exploitation functions normally were carried out by these teams at the corps support area collecting points where they gathered items of intelligence significance needed to meet requirements of the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center. Items to be exploited were evacuated to the center through logistical channels using backhaul transportation as much as possible. Other equipment was released to the collecting point commander for disposition in accordance with service department regulations. Captured enemy materiel requested for retention by capturing units could be returned by the collecting point commander after screening and release by personnel at the center.

The captured material sent to the center was examined and evaluated to determine enemy materiel threats, technological capabilities, and performance limitations; to produce information from which military countermeasures were developed; and to provide continuous input to the national integrated scientific and technical

[43]

intelligence program in accordance with Defense Intelligence Agency and Military Assistance Command policy.

In addition to performing exploitation functions at its fixed facility, the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center also maintained "go" teams to provide field exploitation support when required. These quick-reaction teams were airlifted to objective areas to conduct on-site exploitation of large caches of materiel or items of great intelligence significance.

All materiel in the category of communications and electronic equipment was first screened in accordance with Military Assistance Command directives, then evacuated to corps support area collecting points for examination by technical intelligence personnel.

The complete recovery and expeditious evacuation of enemy ammunition and ammunition components contributed essentially to identifying, weapons systems used by the Communists and a thorough assessment of the threat posed by each weapons system. Large caches of ammunition and explosives had to be inspected and declared safe for handling by explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) teams before evacuation. Hazardous items were segregated immediately and destroyed by these teams, or by unit ammunition personnel if they were qualified to perform destruction. Explosives and ammunition declared safe for handling were evacuated to the ammunition supply point or ammunition depot designated by the ammunition officer of the capturing command where screening, preliminary exploitation, and selection of items for further evacuation to the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center for detailed examination were conducted. The center coordinated preliminary exploitation with the staff explosive ordnance disposal officer at the Military Assistance Command Combat Operations Center to permit technical procedures for safe handling of all first found or newly introduced enemy explosive ordnance to be disseminated promptly throughout the country. All significant items-new, recent, or modified-or enemy material received special handling and were evacuated without delay with captured or recovered technical documents such as gun books, logbooks, packing slips, firing tables, and manuals directly associated with an item of materiel. If the tactical situation did not permit the materiel to be evacuated, a report was forwarded to the Combined Materiel Exploitation Center with a description of the equipment, complete capture data, and other information of value for a technical evaluation of the end item. Photographs of the materiel were highly desirable if the situation permitted.

[44]

The Combined Intelligence Center, Vietnam

The Combined Intelligence Center, Vietnam (CICV), was a true product of the combined concept. It became the most sophisticated and capable production facility I have ever known in direct support of wartime operation and planning.

During the early days of the U.S. buildup it was imperative that we be able to produce intelligence as quickly as possible. It was obvious that we would not have time to bring in the necessary units and specialists from the United States; we would have to make do with the meager resources available in Vietnam. This job was assigned to Colonel Frank L. Schaf, Jr., who had previously served as senior adviser to Colonel Ho Van Loi and as such had become thoroughly familiar with the Vietnamese intelligence organization. This experience, coupled with Colonel Schaf's close personal relationship with our counterparts, contributed importantly to the growth of the combined effort.

While the origin of the Combined Intelligence Center cannot be traced to a simple cell, the Target Research and Analysis Center (TRAC) was important in its evolution. The Target Research and Analysis Center had been created in January 1965 to develop targets for Strategic Air Command B-25's that were scheduled to fly missions in support of Military Assistance Command and was housed in a warehouse located on Tan Son Nhut air base. With the increasing emphasis on targeting, the center grew rapidly; by mid-1965 it constituted a significant portion of Military Assistance Command intelligence. More importantly, existing when the decision was reached to develop the Combined Intelligence Center, it had some available space in the warehouse and served as a handy cadre from which to draw specialists to start the U.S. complement for the combined center. Another aspect of its role in the growth of the Combined Intelligence Center was the rapport that had been developed with the Vietnamese in targeting. The Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces intelligence personnel had become accustomed to working with their Military Assistance Command counterparts, and this provided us a foothold that could be expanded into broader combined intelligence production. The targeting function of the Target Research and Analysis Center was assumed by the Targets Branch of the Combined Intelligence Center under Colonel Edward Ratkovich, U.S. Air Force.

From the limited resources available, Colonel Schaf made remarkable progress in developing the U.S. Element for the Combined Intelligence Center, which at this stage was a unilateral "joint" enterprise. Drawing heavily from the Target Research and Analysis

[45]

Center, the Targets Branch, Support Branch, and Technical Intelligence Branch were fashioned from other elements within the Military Assistance Command intelligence organization. However, there were not enough Americans in Vietnam to man an operation of the scope envisioned, and, though support from the United States would be forthcoming, it would not arrive until late 1965. In, mid-August of that year support from the G-2 of U.S. Army, Pacific, was requested. Augmentation personnel from the 319th Military Intelligence Battalion were sought to bolster our overcommitted, overworked intelligence force until the units requisitioned from the United States began arriving. During the remainder of August and September 1965, the 319th organized and trained a detachment consisting of an area analysis team, seven order of battle teams, and a detachment headquarters-a total of eleven officers and twenty enlisted men. The detachment closed in Vietnam on 15 October 1965. Colonel Schaf quickly assimilated this welcome addition into the cadre of the expanding Combined Intelligence Center. Because space was at a premium, the area analysis team was housed with the Target Research and Analysis Center in the warehouse at Tan Son Nhut while the order of battle teams had to be located in a building in Cho Lon. In early November 1965 we were informed that the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion, which would provide the personnel for the U.S. Complement at the Combined Intelligence Center as well as the combined exploitation centers, had been alerted in August for movement from Fort Brag, North Carolina, to South Vietnam. Except for a small advance party, the battalion would deploy by ship and would require some forty-five days in transit. This delay necessitated a request through Pacific Command that thirty-two critically needed specialists from the 519th be sent immediately to Vietnam by air; thirty-one of these specialists arrived on 25 November and were assigned to production tasks.

Conditions during these early days were less than ideal. Critical deficiencies in work space, billets, transportation, communications, and mess facilities, complicated by a shortage of men and by long duty hours, presented classic problems in management and leadership. Efficiency suffered because some production elements were located at Cho Lon and some at Tan Son Nhut. In pursuit of more space, we double-decked the warehouse at Tan Son Nhut, but the inconvenience of continuing our production functions while these alterations were in process seriously detracted from our effectiveness. Logistical problems confronted the 519th when it arrived, and difficulties in finding suitable billets as well as administrative

[46]

area hindered its integration into the Military Assistance Command intelligence organization. But by early December 1965 the warehouse modifications had been completed and the U.S. Complement for the proposed combined center was fully operational.

The realization of a combined center as envisioned in my earlier agreement with Colonel Ho Van Loi was still some time away. Not only did the Vietnamese lack the requisite qualified personnel, we did not have a facility suitable for housing a combined operation of the magnitude required. Consequently, plans were drawn up for construction of a new building for the Combined Intelligence Center. Since this was to be joint enterprise and would revert to the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces upon termination of the U.S. commitment in South Vietnam, the construction was funded as a Military Assistance Program (MAP) project. Completion of the new building became the target date for activation of the Vietnamese complement for the center.

At the end of 196;1 the U.S. Complement at the Combined Intelligence Center numbered thirty-three men from the 319th Military Intelligence Battalion and 253 permanent party. This number steadily increased as additional elements of the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion arrived; however, we discovered that practically every member of the battalion required either specialized or area training. This added burden had to be placed on the already overtaxed Military Assistance Command intelligence organization and detracted from our capabilities. Despite the inconveniences and difficulties, the 519th soon became operational, and by February 1966 the 319th personnel could be released to return to their parent unit in Hawaii. The Combined Intelligence Center continued to grow and gain in expertise and efficiency. The new building was completed in December 1966, and ribbon-cutting ceremonies marked the official opening on 17 January 1967. The presence of the Vietnamese complement made the occasion particularly significant.

Major Cao Minh Tiep was selected to be the Vietnamese CO-director, and this outstanding officer did much to enhance the combined mission accomplishment of the center.

The new center was reputedly the largest fully air-conditioned single-story structure in Southeast Asia. It eventually housed over five hundred U.S. Intelligence personnel of all services and more than one hundred Vietnamese intelligence personnel working twenty-four hours a day to provide intelligence support to all combat forces in the Republic of Vietnam.

The organization and functions of the center and its individual

[47]

branches, once set up and in operation, remained quite stable. Intelligence production requirements were satisfied in order of battle, area analysis, strategic intelligence, technical intelligence, imagery interpretation, targeting, and intelligence data storage. (Chart 8)

Again, as in other agreements concerning combined intelligence, U.S. And Vietnamese directors controlled their respective elements of the center. Proximity to one another insured that they could easily discuss matters of mutual concern that affected the operation of the center. Once more, I took care to instill the concept of free and complete exchange of information and total cooperation so that no wall of mistrust and suspicion would be generated. In this combined concept, everything had to be open and sincere.

The Support Branch of the Combined Intelligence Center, charged with personnel administration, supply management, security, and maintenance, accomplished these tasks within its Administrative, Security, and Supply Sections.

CHART 8 - ORGANIZATION, COMBINED INTELLIGENCE CENTER, VIETNAM

[48]

The Operations Branch was responsible for production control, which included editing and dissemination of messages and documents, and was organized with Distribution, Graphics, Editing, and Requirements Sections. In this branch also resided the communications facilities for the center. Eventually, through the use of the J-2 teletype, the center communicated with all major U.S. commanders and senior advisers in Vietnam, thus permitting rapid dissemination of significant intelligence to the combat units in the field-a major goal of the center.

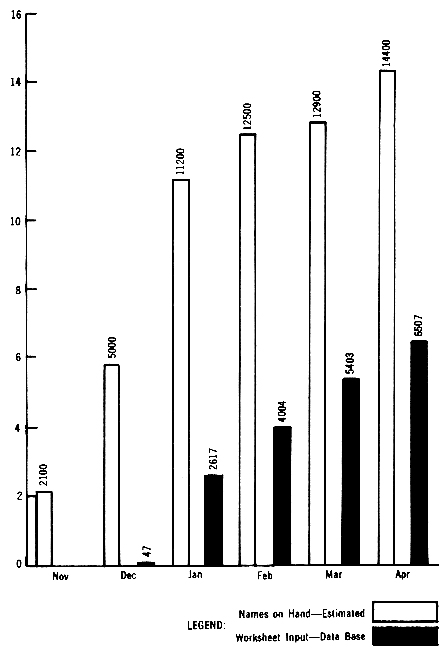

The Automatic Data Processing (ADP) Section automated storage and retrieval of a large portion of the center's data base. The section capably provided analysts and field units with both a narrative printout and a graphic plot of intelligence they required. Although originally designed for support of the Combined Intelligence Center, an equal amount of its work requests were to come from field commanders, both U.S. And Vietnamese. Indeed, many programs were written in Vietnamese. Automatic data processing assistance was as near as the telephone, and, in fact, many units operating near Saigon sent liaison officers to the combined center for more personalized contact. If a particular need required immediate response, the center could have information in the hands of a courier within two hours after receipt of a request. The inclusion of Vietnamese military personnel in the Automatic Data Processing Section, trained to operate all of the equipment and working side by side with U.S. specialists, greatly enhanced the intelligence effort. Bilingual printouts were of immediate value to advisers, who could easily co-ordinate and compare information with their counterparts.

In addition to the administrative and management personnel, the headquarters element of the Combined Intelligence Center included liaison officers to communicate personally with other agencies of the country team and with U.S. And other major command intelligence organizations. Also, some people from the collection side were collocated with the producers in the center to insure accurate and timely response by collectors to the needs of the center for additional data or reconnaissance coverage. Colonel Glenn E. Muggelberg in the Intelligence Operations Division understood that this collocation was undertaken in an effort to resolve a recurring problem which cropped up elsewhere in the vast Military Assistance Command organization: though geographically separated, elements in light of their integrated missions must necessarily work in close cooperation with one another. With the problems of inadequate transportation and the

[49]

scarcity of secure communications that existed in Vietnam at the time, these elements were effectively isolated in their individual compounds. The solution was to put collection directors with the producers in the Combined Intelligence Center.

The Order of Battle Branch (OB Branch) of the Combined Intelligence Center was composed of a headquarters element and three major production elements: Ground Order of Battle (Ground OB) , Order of Battle Studies (OB Studies) , and Political Order of Battle (Political OB) . This branch, which some considered the heart of the center, produced finished intelligence on the eight order of battle factors and on infiltration statistics.

In order to keep its holdings current and complete, the Order of Battle Branch maintained close liaison with other agencies in Saigon (including the other combined intelligence centers) , with tactical units in the field, and with the advisers throughout the country. Frequent field trips to compare and exchange information acquainted the corps analysts with the sources of the various types of information available and at the same time familiarized field units with the type of support the Combined Intelligence Center could provide.

The Ground Order of Battle Section had five teams, one for each corps and a Southeast Asia team concerned with North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia; these teams were charged with developing military order of battle information on their respective geographical areas. We designed the Order of Battle Studies Section along the lines of the order of battle factors: a strength, composition, and disposition team; a tactics, training, and miscellaneous data team; a combat effectiveness team; and a logistics team. This section produced in-depth, countrywide studies on the enemy's forces.

The Political Order of Battle Section was made up of seven teams organized on the basis of enemy military regions and the Central Office of South Vietnam. The section produced complete and timely intelligence on the boundaries, locations, structure, strengths, personalities, and activities of the Communist political organization, or infrastructure.

A fuller understanding of the functioning of the Order of Battle Branch can be obtained by an examination of the general methodology employed by one of the corps teams of the Ground Order of Battle Section. Information entered the section from a great variety of sources including captured documents, interrogation reports from captives and returnees, agent reports, situation reports, and spot reports. Translations of captured documents and

[50]

interrogation reports were appreciated all, by the analyst, who spent most of his time updating his holdings by evaluating and interpreting these sources. Attention also was given to agent reports, which often provided the initial indication of a change in the composition or disposition of enemy forces. Several thousand reports came into the Combined Intelligence Center each week.

When reports came into the Order of Battle Section, they were scanned for information of immediate intelligence value and then passed for detailed examination to the analyst responsible for the particular unit or area concerned. In the case of a captured document, this procedure may have involved requesting a full translation from the Combined Document Exploitation Center. In the case of an interrogation report, it may have involved levying a specific intelligence collection requirement on the Combined Military Interrogation Center with detailed guidance to assist members of the requirements team and the interrogator in fully exploiting the source for order of battle information. As the analyst developed data, he recorded it in a workbook or on cards for future entry in the computer data base.

Within the analytical process, we were concerned with ascertaining not only the existence of enemy units but also the strength of enemy forces. The corps teams of the Ground Order of Battle Section were charged, therefore, with determining the strength of individual combat and combat support units, a factor revealed principally in captured documents, interrogations, and the analysis of enemy combat losses. The Strength Team of the Order of Battle Studies Section developed countrywide estimates of all categories of strength, including that of guerrillas or militia forces. The corps teams supported the Strength Team by supplying information on specific guerrilla units as well as on combat and combat support units as it became available. The analyst's product thus continually revised and modified the branch's order of battle holdings, which were disseminated to field units, to the Military Assistance Command community, and to Washington through both the Monthly Order of Battle Summary, updated daily by cable, and the MACV J-2 Periodic Intelligence Report. (PERINTREP), also published monthly.

The Political Order of Battle Section was concerned with the personnel and organization of the Viet Cong infrastructure from hamlet through national level. Information was received in the section from numerous sources: the National Interrogation Center (NIC) , the combined exploitation centers, corps and division interrogation center reports, agent reports, rallier or Hoi Chanh

[51]

debriefings, American Embassy reports, intelligence summaries, and special collection program reports. Whatever was extracted was placed in the automated data base, which incorporated both the names of individuals within the infrastructure with their known aliases and, using the international telegraphic code, the diacritical marks that are used with the Vietnamese alphabet and are essential for identification purposes. The section could obtain bilingual printouts that could be sent immediately to the field for use in operations directed against the infrastructure.

The Area Analysis Branch had the mission of supporting operations through the compilation and production of intelligence studies on transportation, communications, and military geography. These included tactical scale studies, area analysis base data studies, a Viet Cong and North Vietnam Army gazetteer, and various other special studies concerned with lines of communication, infiltration routes, avenues of approach, and general terrain analysis. In addition, the branch provided input for the periodic intelligence report and estimates and responded to special requests concerning its area of interest. To accomplish these tasks, the branch functioned with an operations element and five subordinate sections: a lines of communication section with teams responsible for highways, 'railways, and waterways; an entry zones section with teams responsible for airfields, helicopter landing zones, drop zones, beaches, and ports; a cultural features section with teams for telecommunications, urban areas, and man-made features; a terrain section with teams handling landforms, vegetation, drainage, and soils; a weather section; and, finally, a support element which was responsible for a map and photo library and a reproduction room.

From January to October 1966 the major effort of the Area Analysis Branch was devoted to establishing a data base and the area analysis studies, which were produced at an area scale of 1:250,000 and were referred to as encyclopedia of intelligence because they provided an excellent reference for intelligence information. Each study consisted of three volumes: Book I was a narrative amplifying the overprinted base map which comprised Book II; Book III supplemented Book II with photos and diagrams. Each study covered friendly and enemy operational aspects-lines of communication, cultural features, and weather and climate. Such studies were completed on all areas of South Vietnam, and 1:250,000 map sheets containing intelligence data were reproduced in 400 copies for distribution to customers. Subsequently, to satisfy requirements for this type of intelligence support, we procured cronaflex (a stable base, mylar material) copies of the joint operation graphic series

[52]

map sheets covering South Vietnam. On the reverse side of each sheet a base map was printed. Intelligence information was then placed on the front of the sheet, and when reproduced on an Ozalid machine, a subdued base map with intelligence superimposed was obtained. Minor changes could be made to the cronaflex sheet without disturbing the base map. Subjects available on cronaflex at a scale of 1:250,000 included cross-country movement, soils, vegetation, geology, and railroads. Originally the plan called for maintaining the data base at this scale, but this proved inadequate for all the information that needed to be plotted. Therefore, the data base was converted to a scale of 1:50,000.

At the same time as the change to 1:50,000 maps, the major emphasis of the Area Analysis Branch shifted to the production of tactical scale studies. The studies were organized into topography, weather, and climate; entry zones; lines of communication; cultural features and telecommunications; cross-country movement; enemy installations; and potential avenues of movement. Except for the first (topography, weather, and climate) , which had only a narrative, each study included a narrative and an overprinted map sheet. They were printed in 350 copies to permit wide dissemination. By mid-1967 tactical scale studies had been completed on almost half of South Vietnam, and the remainder were scheduled for completion by November of that year. The studies were to be revised and republished as required.

The Area Analysis Branch constantly sought to improve the quality and timeliness of its products. One step that facilitated speedy response was the acquisition of the cronaflex map sheets. Road, trail, airfield, and landing zone data were posted to the cronaflex masters each day and the branch was thereby enabled to provide in a matter of minutes annotated maps containing the latest intelligence information. This process was used in conjunction with the rapid retrieval possible with the automated system in the Area Analysis Branch. Within a 36-hour period an Ozalid copy of a tactical scale study could be furnished to a requesting unit. A six-map-sheet study required five days for preparation and assembly and fourteen days for printing by the topographic company that supported the Combined Intelligence Center. It was preferable, if time permitted, to have studies printed rather than reproduced by the Ozalid process.

Approximately 60 percent of the Area Analysis Branch's effort was devoted to the maintenance of tactical scale studies; that remaining was occupied by other terrain intelligence requirements such as input to the periodic intelligence report and estimates,

[53]

TACTICAL SCALE STUDIES PRODUCED BY THE AREA ANALYSIS BRANCH OF CICV were used by all Free World forces in planning operations.

analysis of the effects of the weather on the terrain and enemy capabilities, and the status of routes. Particular attention was paid to requirements for information concerning potential avenues of enemy movement.

Another significant project of the Area Analysis Branch was the preparation of a gazetteer containing 127 1:100,000 Communist map sheets of South Vietnam and reflecting the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese names for places and features. Since the enemy names frequently varied from the South Vietnamese designations, the gazetteer showed the enemy terminology, symbols, and grids with map sheet identification along with the corresponding data that appeared on the U.S. map series. This program was continuous with new names and locales incorporated into the basic document as discovered.

The Technical Intelligence Branch of the Combined Intelligence Center performed equipment analyses, determined weapons and equipment characteristics and specifications, made equipment assessments, and determined vulnerabilities for operational ex-

[54]

ploitation. In order to produce accurate intelligence on enemy capabilities, vulnerabilities, and order of battle in the technical chemical, ordnance, engineer, quartermaster, medical, signal, and transportation areas, the branch was organized with a headquarters and seven technical specialty sections.

In November 1965 action was initiated to have the 18th Chemical Detachment, 571st Engineer Detachment, 521st Medical Detachment, 528th Ordnance Detachment, 590th Quartermaster Detachment, 18th Signal Detachment, and 30th Transportation Detachment assigned to the 519th Military Intelligence Battalion to support the corresponding sections of the Technical Intelligence Branch. Because these were the only technical intelligence units in Military Assistance Command, centralized control was exercised in order to provide the best possible support for the entire command.

The headquarters element handled the operations and administration of the branch as well as requests for technical intelligence assistance. The Chemical Section monitored the enemy chemical capability, with particular interest in decontamination materials, chemical-related documents, and Soviet-bloc chemical equipment and munitions. The Engineer Section accumulated data on enemy fortifications, structures, tunnel and cave complexes, and barriers about which were produced comprehensive studies of Communist construction, installations, and facilities. The Medical Section was concerned with captured medical supplies and equipment as well as medical examinations of prisoners. The Ordnance Section worked on the exploitation of all items of ordnance equipment, while the Quartermaster Section dealt with enemy uniforms and items of general supply. It also provided information for inclusion in various recognition manuals published by the Combined Intelligence Center. The Signal Section, primarily concerned with Communist communications, was especially interested in signal equipment not of U.S. origin.

In addition to the individual section evaluations and reports, the Technical Intelligence Branch as a unit prepared numerous studies and pamphlets on Communist equipment, arms, and materiel. These studies received wide distribution throughout Vietnam and were valuable in training centers in the United States. One particularly important study receiving a high priority and wide distribution was on the enemy use of mines and booby traps.

Finally, the Technical Intelligence Branch of the Combined Intelligence Center developed and maintained the technical intelligence order of battle and provided current information on all of the technical service or support-type units. This information was

[55]

AMERICAN AND VIETNAMESE INTELLIGENCE SPECIALISTS examine a captured enemy rocket launcher.

[56]

published in studies designed to give the customer as much information as possible about the enemy's capabilities and vulnerabilities in the technical service fields. The first such study, NVA/VC Signal Order of Battle, was published during January 1967.

In the Imagery Interpretation (I1) Branch of the Combined Intelligence Center, readouts were made of all types of imagery photo, infrared, and side-looking airborne radar-and furnished to the other branches of the center that required it. The Imagery Interpretation Branch had two sections. The Operations Section was organized along geographical lines with a team for each of the Vietnamese corps as well as out-of-country teams; the Support Section included a film library, a maintenance team, and a photography laboratory. The air-conditioned laboratory, constructed in mid-1967, provided specialized photographic processing support to all branches within the center. Naturally, we attempted to provide the Imagery Interpretation Branch with the most advanced and best equipment available in its field.

A survey team from the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence at Department of the Army and the Automatic Data Field Systems Command in December 1965 came to Saigon on my request. They recommended that we procure certain equipment for the proposed combined center. Their research indicated that the center would need equipment which could accelerate the extraction, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence from aerial imagery. We initiated Project Concrete to secure the needed equipment and submitted requisitions on 13 December 1965. The first shipment of Project Concrete imagery interpretation equipment arrived on 15 December 1966 and consisted of twelve simple roll-film light tables to be used with zoom optics, two AR 85 Viewer-Computers, three Itek rear-projection viewers, and a CAF Model 910 Ozalid printmaster. The second shipment arrived on 14 January 1967 and included four AR 85 Viewer-Computers, one Map-O-Graph, three Itek variable-width viewers, a microdensitometer with clean-room module, and one photo rectifier. The final shipment came late in February 1967 and included six multisensor take-up tables with a supply of replacement parts.

The AR 85 Viewer-Computer was designed to perform rapid and accurate mensuration on all types of imagery-infrared, radar, and photography, including panoramic photographs. Some of the more important functions performed by the computer included determination of true ground position expressed either in geographic or universal transverse mercator co-ordinates, determination

[57]

of height, area measurement, and measurement of straight or curvilinear distances. A typical project on which these machines were employed was the analysis of rice production in the IV Corps Tactical Zone.