- Between 1946 and 1948, while Congress debated regular and reserve status for women in the armed services, the Army staff and Colonel Hallaren and her staff conducted business as if the women's integration legislation would pass. The director of organization and training (DOT), formerly the assistant chief of staff, G-3, optimistically directed that a site for a new WAC training center be selected. Colonel Hallaren and her staff prepared plans for the new center and an officer candidate school. Among themselves and with Army commanders in their geographical areas, WAC staff directors discussed the future of the WAC and the possible establishment of additional WAC units. Then, on 12 June 1948, the Women's Armed Services Integration Act became Public Law 625. Colonel Hallaren set in motion the approved regulations for the new WAC. Only then did she have time to reflect on the future: did the WAC have the right organization, mission, and personnel to manage the Corps in the Regular Army and Reserve and to conduct training operations?

- The mission of the director of the WAC (DWAC) on the General Staff had changed little since 1943. By law, she was the primary adviser to the secretary of the Army on WAC matters and was responsible for ensuring that the Army's staff agencies issued appropriate plans and policies concerning the supervision, morale, health, and safety of WACs. She was the primary adviser to the chief of staff and members of the Army staff on regulations and other matters concerning the WACenlisted recruiting, officer procurement, classification, utilization, training, assignment, housing, supply, discharge, and morale. She ensured conformity to those regulations and policies by inspecting WAC units and personnel worldwide. She also maintained liaison with civilian and governmental agencies and with other women's services in the armed forces of the United States and its allies.1

- Under the new law, the WAC director would also serve as an adviser to the WAC Section, Organized Reserve Corps (ORC); each of the chiefs

- [63]

- of the Army's technical and administrative services monitored and advised his particular reserve section. Colonel Hallaren had been unable to preclude the creation of a separate WAC section in the Organized Re;erve, but she had won a small victory by convincing the executive for reserve and ROTC affairs not to establish WAC detachments within the ORC. Thus, WACs were to be commissioned and enlisted in the WAC Section, ORC, according to the law, but they were to be assigned to existing men's units for administration, training, supply, and discipline. The director and her staff would advise the executive for reserve and ROTC affairs, through his WAC adviser, about entry into the Organized Reserve and subsequent training, utilization, retention, and mobilization of WAC reservists. 2

- In early 1946, while the Army shifted to peacetime operations, General Paul, the G-1, had reorganized his office. He had added a new positions special assistant for women's affairs. As an additional duty, the director of the WAC would fill the position and advise the G-1 on matters pertaining to all women in the Army, not just WACs, but all women in the Army.

- Colonel Boyce, then the director of the WAC, sent a stiffly worded memorandum to General Paul stating that the task of advising the G-1 on all women in the Army was "beyond the ability and authority" of the director. She wrote, "it is deemed inappropriate to include in your chart that the Director WAC will perform the duties of the Special Assistant for Women's Affairs." 3 Colonel Boyce knew that the chief of the Army Nurse Corps and the senior women medical specialists would object to her advising the G-1 on their professional status and career development. Conversely, if the head of the Army Nurse Corps had been assigned the role of special assistant, Colonel Boyce would have vehemently objected. General Paul did not change his organizational chart, but, swayed by Colonel Boyce's objection, he did not assign this additional duty to the WAC director or to anyone else. He did, however, retain the proposed slot so that if, during hearings on the WAC bill, Congress complained about establishing three separate women's organizations within the Army, he could show that the women's services had been unified under a special assistant for women's affairs.4

- Even though General Paul's move to enhance the WAC director's status with the additional responsibility had not worked out, he remained concerned about where the director's position would fit in the Army's

- [64]

- postwar hierarchy. 5 The placement of the director's office under the G-1 had worked well, but, in November 1947, General Paul had arranged for it to be placed under the chief of staff. The action improved the director's prestige with Congress and impressed on the legislators the Army's high regard for the WAC and the desirability of regular Army status for women. 6

- As in any hierarchy, much depends on the relationship a subordinate builds with a superior; and the success of any WAC director depended largely upon her relationship with the G-1 or, as that position had been redesignated, D/PAD. She needed his confidence in her decision making, knowledge of WAC matters, and leadership. On appointment, of course, she had his goodwill and trust-he held the key role in her selection. Problems, however, occasionally arose when a change in the D/PAD position occurred, as it did almost every two years. Colonel Boyce, for instance, had served amicably as deputy director and as director under Maj. Gen. Stephan G. Henry, the G-1 during 1944 and 1945. She had not served so compatibly under General Paul, who became G-1 in October 1945. The crux of their difficulty was Colonel Boyce's dedication to carrying out Colonel Hobby's plan to disband the WAC. General Paul was committed, instead, to carrying out General Eisenhower's orders to get the WAC into the Regular Army and the Organized Reserve Corps. It was not surprising that, fifteen months after they met, Colonel Boyce had retired and the bill providing for regular and reserve status for WACs was in Congress for the second time.

- The WAC director worked closely with the D/PAD. She usually attended his weekly staff meetings along with the adjutant general, the provost marshal general, the chief of chaplains, and the chief of special services. Also in attendance were the chiefs of the three major groups within the Directorate of Personnel and Administration: Career Management Group, Manpower Control Group, and Military Personnel Management Group. Through these meetings and associations, the director participated in Army personnel planning and had a forum to explain the impact of Army-wide policies on the WAC and to announce WAC plans and policies to the other personnel policy makers in the Pentagon.

- By the end of October 1948, the Office of the Director, WAC (ODWAC), consisted of five officers, three enlisted women, and a civilian secretary. The officers included the director, her deputy, an executive officer, a career management officer, and a technical information officer.7

- [65]

-

WAC STAFF ADVISERS AND SENIOR WAC OFFICERS CONFERENCE, the Pentagon, September 1949. Left to right, front row: Maj. Virginia Mathew, Maj. Mary M. Pugh, Maj. Mary K. Moynahan, Maj. Charlee L. Kelly, Col. Mary A. Hallaren, Director, WAC, Lt. Col. Mary L. Milligan, Deputy Director, WAC, Lt. Col. Elizabeth C. Smith, Maj. Irene O. Galloway, Maj. Geneva McQuarters, Maj. Selma Herbert, Maj. Ruby Herman, Maj. Margaret M. Thorton, Capt. Sue Lynch, Lt. Hazel Glynn. Second row: Maj. Mary C Fullbright, Maj. Bernice Hughes, Maj. Mary E. Savage, Lt. Norma J. Fisher, Capt Ellen Dunbar, Maj. Mary Jo Key, Maj. Cloe E. Doyle, Maj. Fannie Reynolds, Maj. LaVern F. Noll. Capt Beatrice Parker, Capt. Lucile G. Odbert, Maj. Ruth Reece, Capt. Mary Warner. Third row: Capt. Marjorie Schulten, Lt. Dorothy Frome, Capt. Helen Cooper, Maj. Alene Drezmal, Maj. Hattilu C. White, Maj. F. Marie Clark, Maj. Eleanore C Sullivan, Maj. Beatrice Ringgold, Capt. Martha D. Allen, Maj. Elizabeth W. Bianchi, Maj. Anne E. Sweeney, Maj. Ethel S. Moran. Back row: Maj. Cora M. Foster, Capt. Helen Roy, Maj. Anne K. Hubbard, and Maj. Margaret A. Long.

- The career management officer worked in the officers' assignment office in the Career Management Group and managed WAC officer assignments and career development actions. The technical information officer was added to the staff to disseminate WAC plans and policies to the field and to coordinate WAC public relations.8

- The director's primary link to WAC officers and enlisted women was the WAC staff director. Because the MOS (2145) for that position had to be filled by a WAC officer, the WAC director selected and nominated

- [66]

- staff directors for each major command. These staff directors, assigned to the command's D/PAD, acted as the commander's WAC expert and troubleshooter and attended his weekly staff meetings. Through their regular inspections of WAC units, the staff directors became well known to post commanders, staff officers, and WACs throughout their particular command. Their knowledge and contacts made it easier to solve problems, distribute information, and gather statistics. If a staff director could not resolve a problem within a command, she sought the assistance of the director and her staff at the Pentagon. In January 1949, the WAC staff director's title was changed to WAC staff adviser, a title more descriptive of her duties.9

- The responsibilities of the staff advisers increased rapidly. At the WAC Staff Advisers Conference in September 1949, Colonel Hallaren reported that twelve WAC detachments had been established or reactivated during the year. Four of the twelve were segregated black detachments stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey; Fort Knox, Kentucky; Fort Lewis, Washington; and Kitzingen, Germany. Other new or reactivated detachments were assigned to post headquarters complements at Fort Belvoir, Virginia; Fort Bliss, Texas; Camp Gordon, Georgia; Camp Holabird, Maryland; and Fort Sheridan, Illinois. The remaining new or reactivated detachments were at the Army Finance Center, St. Louis, Missouri; the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York; and Brooke General Hospital, Fort Sam Houston, Texas. With these additions, the WAC had a total of fifty-seven units, with eleven overseas (seven in Germany, one in Austria, two in Japan, and one in the Canal Zone). 10

- Throughout the war and postwar years, many WAC officers had been assigned to positions in various General and Special Staff divisions at the Pentagon. In addition to her other duties, the senior WAC officer in a division became its expert on staff actions regarding the Corps. Through demobilization, most of these jobs were vacated between 1945 and 1947. Drastic reductions in military personnel precluded the assignment of replacements, and division chiefs, lacking the advice of these experts, gradually forwarded more and more WAC staff actions to the director's office for information, advice, and solution.

- In October 1946, Colonel Boyce submitted an urgent request to the chief of staff for assistance, noting that a "large volume of papers, corre-

- [67]

- spondence, and inquiries" were being referred to her office "for initial study, preparation, and action." She pointed out that her five-woman staff was too small to handle the additional work.11 The director asked that a WAC staff officer with the primary (but not sole) duty of preparing WAC staff actions and studies be assigned to divisions that had a high volume of such actions. Her request was approved and within a few days the chief of staff directed:

- There will be assigned to the Office of Director or Chief of each General or Special Staff division to whom this memorandum is addressed, a WAC officer who is mutually acceptable to the division director or chief and to the Director, WAC, and who will be responsible for advising the director or chief on all matters pertaining to the Women's Army Corps.12

- By the end of the year, each designated division had a WAC staff action officer. Colonel Hallaren, on becoming director in the spring of 1947, formed a WAC Plans and Policy Committee from that group of officers. The committee was to meet when needed to review Department of the Army staff plans and policies that might affect the WAC and to make recommendations concerning WAC operations. During the next few years, the committee met infrequently. In 1950, with the Korean War, the group's activities were stepped up as the Corps expanded; but, thereafter, the committee again met infrequently and was eventually discontinued. By the end of 1951, the divisions had designated appropriate spaces in their manning documents for WAC staff action officers, and WAC officers were routinely requisitioned to fill these positions.13

- During its first two years in the Regular Army, the WAC had few lieutenant colonels. When the integration bill became law on 12 June 1948, the Corps had three. A few days later, on 16 June, one of these women, Lt. Col. Geraldine P. May, was transferred to the Air Force, promoted to temporary colonel, and appointed the director of Women in the Air Force. Only two lieutenant colonels remained: Deputy Director Milligan and Lt. Col. Kathleen McClure, WAC Staff Director, Headquarters, U.S. Army, Europe. In November, however, a few months after returning from Germany, Colonel McClure transferred to the Air Force and was assigned to the Pentagon.14

- [68]

- At the time, the WAC had little hope of obtaining additional lieutenant colonel slots. Under the rules for integration into the Regular Army, neither men nor women could be appointed in the Regular Army in a grade higher than major. In addition, the Officer Personnel Act of 1947 (PL 80-381) had included a new promotion system for the Army. This law stipulated that no permanent promotions could be made in the WAC until 12 September 1949, fifteen months after the Integration Act was signed; no temporary promotions could take place until after the women's first Regular Army promotions had been made.15

- General Paul, however, had anticipated problems in obtaining promotions for WACs and had included two special provisions in the integration law. The secretary of the Army was authorized to designate specific WAC administrative and training positions at the grades of lieutenant colonel and major. He was also empowered, until 1 July 1952, to grant temporary promotions to women selected for those positions. Thus, even though promotions were initially very restricted, the WAC could promote officers on a permanent basis beginning in 1949 and, until mid-1952, could add additional temporary officer personnel, as necessary. By that time, the new officer personnel law was expected to provide a sufficient number of women at the proper grades. If it did not, the secretary could have the . temporary promotion authority extended.16

- A new Army staffing regulation followed the enactment of the integration law. Under its authority, delegated by the secretary of the Army, Colonel Hallaren designated certain key WAC administrative and training positions at the maximum allowable grade. Of these positions, only those authorized for the new WAC Training Center were not yet filled. The other positions had incumbents, but not all of those officers had reached the grade authorized by the new regulation. The subsequent special regulation instructed the major commanders who controlled these positions to add the following to their manning documents:

- Lieutenant Colonels

- Executive Officer, Office of the Director, WAC

- Chief, WAC Career Branch

- Adviser, WAC Reserve Section, Office of the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs

- Commander, WAC Training Center, and Commandant, WAC School

- Assistant Commandant, WAC School

- Basic Training Battalion Commander, WAC Training Center

- [69]

- Advanced Training Battalion Commander, WAC Training Center

- WAC Staff Advisers at the following commands:

- The six Continental Army commands in the United States

- Headquarters, Military District of Washington, Washington, D.C.

- Headquarters, U.S. Army, Europe Headquarters, U.S. Army, Far East

- Majors

- Two battalion commanders, WAC Training Center 17

- In early 1950, with the integration phase moving into its last months and the freeze on permanent promotions lifted, a number of WACs were promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Five permanent promotions, including Director Hallaren's, came through in January. Six new temporary promotions were announced before the end of the year, two in May and four in November.

- With the new decade, the women's services gained the assistance of a civilian advisory group-one composed of women. The idea for the group stemmed from a recommendation made by Mary Pillsbury Lord, chairwoman of the National Civilian Advisory Committee on the WAC, at its final meeting in October 1948. She recommended that each service appoint six civilian women, leaders in their fields, to advise the service secretaries and the secretary of defense on matters pertaining to women in the armed forces. General Bradley, Army Chief of Staff, promptly approved the idea, but it was not implemented until April 1949. At that time, the Department of Defense (DOD) hired Dr. Esther B. Strong and appointed her Representative of Women's Affairs on the DOD Personnel Policy Board, which had been established in February. Dr. Strong, who held a doctorate in sociology from Yale, took up Mrs. Lord's recommendation.18

- [70]

- A year later, Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson invited a number of nationally known women to the Pentagon to discuss issues affecting military and civilian women employees of the department, to learn about the department, and to consider forming an advisory group for women in the services.19 Hosted by the Personnel Policy Board, the conference was held on 21 and 22 June 1950. Among the civilian attendees were Mrs. Lord; India Edwards, Director, Women's Division, Democratic Party; Anne Wheaton, Director of Publicity, Republican Party; Dorothy Ferebee, President, National Council of Negro Women; Dr. Margaret Craighill, Chief Consultant on Medical Care for Women, Veterans Administration; Frances Diehl, representing the General Federation of Women's Clubs; Margaret Hickey, lawyer, educator, and writer for the Ladies Home Journal, Marie B. Johnson, representing the United Council of Church Women; Dr. Dorothy C. Stratton, former director of the SPARS; Dr. K. Frances Scott, President, National Association of Business and Professional Women's Clubs; Katherine Densford, past president of the American Nurses Association.20

- The conference started with briefings on the national defense establishment, its various branches, and its long-range plans for women in the military. Four of the women military leaders, Col. Geraldine P. May of the Air Force, Captain Hancock of the Navy, Col. Mary G. Phillips of the Army Nurse Corps, and Colonel Hallaren, then gave talks on "The Historical Background of the Women's Military Services," "The Present Utilization of Military Womenpower," "Women in Medical Service," and "Mobilization Planning for Military Women."21

- On the second day, the women discussed the department's plans, programs, and policies concerning women. And, at the meeting's end, they agreed to forward, individually, to Dr. Strong any conclusions on such issues as registering and drafting women, assigning women to combat zones, and forming a permanent women's advisory committee. All participants wanted more time to assess the roles for women in the military and to consider the opinions of those they represented. Conference Chairman J. Thomas Schneider, of the Personnel Policy Board, adjourned the group by saying, "I know we are going to get a great deal of value out of your reviewing with us the program of the Department of Defense .... We will welcome your suggestions, your counsel, and your advice." 22

- [71]

- The Sunday after the conference, on 25 June, the Korean War began. A little over a year later, the women were again contacted. In August 1951, approximately fifty outstanding civilian women leaders-most of those who had attended the 1950 conference-were asked to serve a oneyear term on the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS). Forty-four women accepted appointments, including Mrs. Hobby, the first WAC director; Mildred McAfee Horton, former director of the WAVES; Dorothy Streeter, former director of the Women Marines; Helen Hayes, actress; Sarah G. Blanding, president of Vassar College; Lillian Gilbreth, engineer; and Beatrice G. Gould, editor and publisher. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Personnel Anna M. Rosenberg announced that the women would help develop policies and standards for military women in such areas as recruiting, utilization of women, expansion of career opportunities, housing, education, and recreation. The formation of the committee ensured that women had representation at the Department of Defense level. 23

- The original site selected for a training center for the proposed WAC had been Fort Knox-chosen by Maj. Gen. Idwal H. Edwards, Director, Organization and Training, from posts recommended by Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, Commanding General, Army Ground Forces, who was to have responsibility for the training center.24 Colonel Boyce objected so vehemently to the isolated, run-down area available at Fort Knox that General Edwards ordered a second survey of possible locations. After a ten-month search, the new site selection committee, which included Colonel Boyce and other WACs, reported that only three of the posts visited had adequate housing and classroom space, and, of those three, Camp Lee, Virginia, was their first choice. General Paul and Lt. Gen. Charles W. Hall, who had succeeded General Edwards, concurred.25

- Meanwhile, the commander of the Army Ground Forces, uncomfortable with the responsibility for WAC training, asked General Hall to transfer the function to an agency with concerns more compatible with

- [72]

- the WAC's training needs-his command was primarily involved with ground combat training. As a result, in June 1947, General Hall transferred responsibility for WAC training to the adjutant general (TAG) of the Army.26 The change was appropriate and convenient because the adjutant general's department primarily performed administrative functions, such as personnel, recruiting, and postal operations. Its role was akin to the administrative nature of most WACs' duties. At General Hall's direction, The Adjutant General's School moved in September 1947 from Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, to Camp Lee.27 To manage his new responsibilities, Maj. Gen. Edward F. Witsell, TAG, proposed a reorganization. He would create The Adjutant General's Training Center at Camp Lee which would include The Adjutant General's School with the WAC Training Center attached to it. A brigadier general would command this new organization. 28

- Colonel Hallaren, by this time the director of the WAC, opposed the plan. She wanted the WAC Training Center to have as much status as TAG School; she wanted the training program to offer WAC officer candidates and NCOs positions from which they could gain leadership experience. The center would be the model for future centers, and it would provide the "trained cadre for any such organization as might be required upon mobilization."29

- To settle the matter, Colonel Hallaren held a conference, in November 1947, with representatives of the appropriate Army agencies. They agreed that the WAC Training Center should be "a complete functioning unit under the TAG Training Command," not a subsidiary of TAG School. This agreement ensured maximum autonomy for the WAC Training Center.30

- The agreement, however, was not implemented. A major reorganization of the Army, in March 1948, replaced Army Ground Forces with Army Field Forces, with its commander becoming the Army's chief training officer. 31 The WAC Training Center was now given a numerical designation, the 2004th Army Service Unit, and placed under the commanding general, Second Army, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland.32

- [73]

- MAJ. ANNIE V. GARDNER, Acting Commander, WAC Training Center, Camp Lee, June 1948.

- The proposed training site for Women in the Air Force (WAF) had changed several times during 1947 and 1948. Early in 1947, planners for the Army and the proposed Air Force had decided that the WAC and WAF would train together. But after the National Security Act was signed, making the Air Force a separate military department, the Air Force opted for separate training and prepared a plan to train its own women. 33 The 3741st WAF Training Squadron at Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas, would conduct basic training for WAFs. According to the plan, USAF specialists' training in such areas as air traffic control, photography, radio, and weather observation would be open to enlisted men and women. Women officer candidates would also train with men; in January 1949, 25 enlisted women joined 250 enlisted men at the USAF Officer Candidate School at Lackland.34

- In March 1948, when the commander of the Army Field Forces became the Army's chief training officer, he lacked much of the authority held by his predecessor, the commander of the Army Ground Forces. He did not have command authority over the six CONUS armies, which now reported instead to the Army chief of staff. He did not control training spaces, training funds, and missions. Camp Lee came under the authority of Lt. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, Commanding General, Second Army, at Fort Meade, approximately 125 miles northeast of the camp. He con-

- [74]

- SOME OF THE BETTER LOOKING BARRACKS In the 2d Battalion area, WAC

- Training Center, Camp Lee, August 1948.

- trolled funds and personnel spaces to support all posts within his geographical area. Support included everything from medical care and treatment to food, recreation, transportation, repairs, and utilities.35

- Although the training center commander would be selected from the WAC, General Gerow delegated to the post commander at Camp Lee, Brig. Gen. Roy C. L. Graham, supervisory control of the WAC Training Center. General Graham, therefore, became the rating officer for the WAC commander's operation and management of the center. The director of the WAC had no direct authority over its operation. However, because she was the chief of the Corps, plans affecting the center and school were referred to her office for comment.36

- Activation of the WAC Training Center

- Colonel Hallaren wasted no time after the Integration Act gave the WAC regular and reserve status. She immediately moved women to Camp Lee. Within two days, Maj. Annie V. Gardner and Cpl. Wanda E. Pinkney reported to General Graham. On 15 June 1948, the WAC Train-

- [75]

- ing Center was officially activated with Major Gardner as acting commander.37 To fill the position of commander of the training center and commandant of the Officer Candidate School (OCS), Colonel Hallaren selected Maj. Elizabeth C. Smith and obtained a temporary promotion for her to lieutenant colonel under Public Law 80-625. Colonel Smith, who had been assigned to the Office of the Director of Organization and Training since 1943, was recognized as the Army staffs expert on WAC training and had been a member of every major board and committee concerning the WAC.38

- While WACs had not been pampered by elegant living at their World War II training centers, the WAC area at Camp Lee discouraged even those who had lived in the converted stables at Fort Des Moines or the converted POW camps at Fort Oglethorpe, Fort Devens, and Camp Ruston. In addition, when the wind at Camp Lee was right, sulphurous smoke from a nearby chemical plant permeated the air at the installation. One WAC officer considered "stable row at Fort Des Moines ... the Ritz Canton in comparison."39 Another described the center as having been "activated in a section of the camp that had been unoccupied for two-and-a-half years and which had become a wilderness of weeds, underbrush, dilapidated buildings, and the inevitable training center mud."40

- The wood-frame buildings in the WAC area were uninsulated, had unfinished interior walls, sat on concrete blocks high enough to allow for water and drain pipes, and were heated by coal furnaces that were fed by hand shovel twice a day during the winter months. Most one-story buildings contained orderly rooms, supply rooms, or dayrooms; the twostory buildings served as either barracks or classrooms.

- Each floor of a barrack contained army cots, footlockers, and steel wall lockers, approximately forty-five of each, along with two small rooms that were reserved for platoon sergeants who supervised the trainees, day and night. Officer candidates and student officers had partitions between every two beds which provided some privacy but interfered with adequate ventilation. Permanently assigned officers lived in twostory buildings that had private rooms or permanent partitions. Lieutenant colonels and majors had single rooms; captains and lieutenants had to double up. Each building had a makeshift kitchen, a reception room for visitors, and a dayroom. And, while none had private baths, Army regu-

- [76]

-

WAC TRAINING CENTER COMMANDER AND HER IMMEDIATE STAFF, Camp Lee, September 1948. Left to right: Maj. Annie V. Gardner, Commander, 1st Battalion; Capt. Emily C. Gorman, S-3; Capt. Margaret E. Onion, Executive Officer; Lt.Col. Elizabeth C. Smith, Commander,' Capt. Lillian F. Foushee, S-4,' and Capt. Hattilu C White, Information Officer.

- lations specified that women's barracks had to contain at least one bathtub per seventy-five women in addition to individual showers.41

- The officers and enlisted women who would conduct the training, administration, and supply operations at the training center began arriving early in July. They undertook the back-breaking task of cleaning buildings and grounds and moving furniture and supplies. The pace was hectic; but the center would be ready to begin training recruits, officer candidates, leaders, and clerk typists in October. Colonel Smith later described their efforts:

- Looking back it seems to me that the pioneers who made the beachhead landing at Camp Lee are certainly entitled to campaign ribbons and maybe even battle

- [77]

- stars .... Their devotion to duty, their investment of time, physical labor, and constructive thought . .. produced a training establishment of which we as a Corps can be proud .42

- Colonel Smith arrived at Camp Lee on 3 August. The next day, General Graham hosted a ceremony for her as she assumed command of the training center. Major Gardner then assumed command of the newly activated 1st Battalion (Basic Training) to complete the change in leadership at Camp Lee .43

- Colonel Hallaren was dismayed when she visited Camp Lee for the first time since viewing it as a member of the site selection committee. Promises from Army Field Forces about improving the WAC area had not been kept. After inspecting it on 24-25 August 1948, she wrote to General Gerow: "The barracks at the far end of the Training Center where new recruits are to be housed are in extremely poor condition. Great strips of paint have peeled off the barracks resulting in a rotting of the exposed wood and an outside appearance which would deter an observer from volunteering."44

- Colonel Hallaren requested funds and equipment to rehabilitate the buildings. She appealed for electric fans for the classrooms and offices and paint for the interiors and exteriors of buildings. Fans were in short supply, but General Gerow rushed as many as possible to the center, two from his own quarters at Fort Meade. Obtaining funds for the needed paint was more difficult-funds for painting "temporary buildings" except for "sash doors, trim, and exposed metal" was prohibited. Eventually, however, General Gerow was able to obtain almost $400,000 in appropriated funds for rehabilitating the buildings during fiscal year (FY) 1949.45

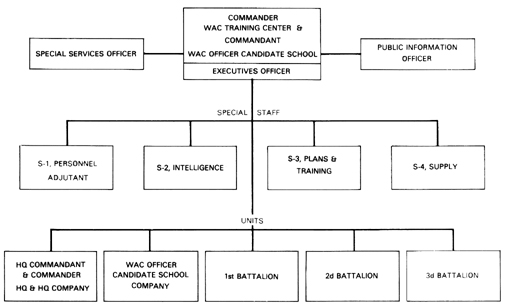

- The organizational structure adopted for the WAC Training Center followed the lines of a regimental command. The training center commander had a personal staff consisting of an executive officer, special services officer, and public information officer. She also had a traditional staff (S-1, Personnel; S-2, Intelligence; S-3, Plans and Training; S-4, Supply). The WAC units under her command were Headquarters and Headquarters Company; the 14th Army Band (WAC); 1st Battalion with five lettered companies to conduct basic training; 2d Battalion with three

- [78]

CHART 1- WAC TRAINING CENTER, FORT LEE ORGANIZATION, 1948

- Source: Annual History, WAC Training Center, 1 Jun-31 Dec 48, App A, History Collection,

- WAC Museum.

- companies: one for leadership training, one for reenlistee processing, and one, a holding company, for housing and processing trainees awaiting discharge, board action, or transfer; 3d Battalion with one company for women attending the typing and clerical procedures course, one to oversee students enrolled in other specialist courses at Camp Lee, and one for women attending WAC Officer Candidate School (see Chart 1).46

- The WAC Training Center was staffed entirely by women from WAC detachments in the CONUS armies. But the commanders of these detachments often objected to reassigning their ablest women to the training center, and the women themselves frequently disliked being transferred into an all-female environment. Still, the WAC planners insisted that commanders fill the training center requisitions with qualified women and would not accept enlisted men or male officers as substitutes. The planners wanted to avoid the problems experienced during World War II when some of the male trainers had carelessly performed their duties, had been hostile to women senior officers, and had hazed the trainees without the officers' knowledge.47

- [79]

- The training center was officially opened on 4 October 1948. By that time, WACs had cleared the weeds, made the classrooms habitable, and prepared the class schedules. The first event was a review on the WAC parade ground, commonly called "the Black Top" because its surface was a thick layer of asphalt, which on hot days would soften and move underfoot and on cold days would develop holes and bumps-significant hindrances for marchers. Three battalions of men from the post and two companies of WACs marched in this first parade. The guests then moved to the WAC theater nearby for an opening ceremony. Colonel Hallaren, principal speaker for the occasion, commended the permanent party on their efforts and proclaimed the new WAC Training Center officially open and ready to train women for the Regular Army. Representatives of the other women's services attended the ceremony: Col. Geraldine P. May, Director, Women in the Air Force; Maj. Julia E. Hamblet, Acting Director, Women Marines; Lt. Comdr. Sybil A. Grant, representing Capt. Joy Bright Hancock, Director, WAVES.

- On 6 October, two days after the ceremony, Colonel Smith welcomed the first trainees. The first recruit to arrive directly from civilian life was Macseen Sutton of Boone, Nebraska; the first reenlistee to report for processing was Pfc. Alice W. Roseberry of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. On 13 October, Colonel Smith formally received the black WAC officers who would command and train black recruits in Company B, 1st Battalion Capt. Bernice G. Hughes, Commander; 1st Lts. Doris H. Williamson, Ann G. Hall, and Catherine G. Landry. The first black recruit to arrive was Callie L. Hawthorne of Kilgore, Texas.48

- Almost every week during the next few months, a "first" or an "opening" at the center drew high-ranking guests. All of these events were well publicized by the public information officer, Capt. Hattilu C. White. The WAC theater opened on 19 September, showing movies three nights a week. The WAC Cadre Club (later called the Enlisted Open Mess) opened with a dance on 2 October. Maj. Gen. William H. Middleswart, Assistant Quartermaster General of the Army, his wife, and Colonel Smith were the guests of honor. A beauty shop opened on 25 October, and near it the WAC PX opened on 4 November. The first marriage at the WAC chapel took place on 13 November 1948; Sgt. Katie Kucher married Edmund Zielinski. In accordance with local custom, racially segregated WAC service clubs opened on 29 October for whites and on 19 November for blacks; USO clubs opened in Petersburg, Virginia, on Byrne Street for whites and on Wythe Street for blacks. Tennis courts and a hobby shop opened in the WAC area in November and December.

- [80]

- The first graduation of Regular Army WAC basic trainees on 10 December 1948 was a major event. Company A, 1st Battalion, had trained the graduates. Both General Paul and Colonel Hallaren attended the event, and the former gave the graduation speech.

- Inspections, an everyday part of life at the training center, ranged from the daily walkthrough of the barracks by the first sergeant to visits by teams from the Office of the Inspector General. A team of officers from Headquarters, Second Army, and the Office of the Chief of Army Field Forces conducted the first major inspection at the center between 13 and 16 December. The training center received a superior rating for all aspects of training and administration during its first three months of operation.

- In March 1949, the arrival of the all-female 14th Army Band (WAC) raised the morale of the women at the training center. The WAC Band, as it was commonly called, had been activated at Fort Meade on 11 August 1948 and had assumed the lineage of the 400th Army Band (WAC), which had served at Fort Des Moines and Camp Stoneman, California, before being deactivated in April 1947. The WAC band arrived with bandmaster WOJG Katherine V. Allen and a few reenlistees from the World War II WAC bands. These women had assembled their instruments, music, and equipment while attached for training to the 51st Army Band at Fort Meade. To bring its complement up to the thirty-four authorized, recruits were auditioned while still in WAC basic training, and if they met Miss Allen's high standards, they were assigned for duty with the band upon graduation. By the end of June 1949, the band had twenty-six musicians and was playing for WAC parades on the Black Top and at orientation ceremonies, graduations, retreats, and other troop formations.49

- Training Missions

- During its first two years, the missions of the WAC Training Center were clarified. One mission briefly imposed on the center in 1948 by the Army's director of training was that of providing overseas training for all WACs. During World War II, this task had been accomplished by an activity called Extended Field Service at the Third WAC Training Center, Fort Oglethorpe. Men, on the other hand, received overseas training at depots throughout the United States. The end of the war had eliminated the need for these large depots, and a new system was begun whereby each post conducted the appropriate training for men who

- [81]

- received overseas orders. By March 1948, this system was in effect throughout the Army. In June, pending completion of a review by the office of the Director, WAC, to determine whether women too should )e trained in this way for overseas duty, the mission was assigned to the WAC Training Center. Later in the year, Colonel Hallaren recommended to the director of organization and training that post commanders provide Overseas training and processing for WACs as well as men. The WAC Erector's review convinced her that establishing a separate facility solely :or women would increase training and travel costs. Her recommendation was approved, and, in March 1949, the commanding general of the Second Army deleted the mission as a WAC Training Center responsibility and included women under the Army regulation on this subject .50

- In the summer of 1950, the training center took on the mission of diving basic training to women of the WAC Section, Organized Reserve Corps. Customarily, the reserve units gave basic combat training to male enlistees, with over half of the time devoted to weapons use and tactical training for infantry units. As this kind of training was inappropriate for the duties to which WAC reservists would be assigned, a two-week, active-duty basic training program was introduced for them. The 88-hour program, conducted at the WAC Training Center, was preceded by 12 pre-active-duty training hours at the reservists' home units. As part of the 88-hour program, reservists studied the achievements and traditions of the WAC, military customs and courtesies, drill and ceremonies, first aid, snap reading, military justice, physical training, marches and bivouac, Army administration, and wearing of the uniform.51

- Although the Army had six training centers for men, it needed only one for training WACs in peacetime. One-third the size of the World War II facilities, the center at Fort Lee carried out every function the earlier centers had performed-except overseas training. Its mission was "to prepare the woman soldier for the job she will be assigned in the Army; to indoctrinate her into the elements of military life and customs; and to imbue her with the high moral and ethical standards which the Army demands." 52 To perform this mission, the center acted as a reception and processing center and a replacement training center for recruits; a specialist training center for graduates of basic training; a school for officer candidates and potential enlisted leaders; and a reserve training center. Its maximum training population was 1,547. (See Table 3.)

- [82]

- Source: WAC Training Center, "History of the WAC Training Center, 30 June 1948 to 31 December 1953," History Collection, WAC Museum.

- The basic training battalion received, processed, and trained the newly enlisted women. Their first week was devoted to initiating their Army personnel file, receiving immunization shots and a dental check-up, being fitted for uniforms, and taking tests. Each also received a $10 cash advance on her monthly pay of $65. The eight-week training program included such subjects as military customs and courtesies, organization of the Army, military justice, personal hygiene and military sanitation, social hygiene, first aid and safety measures, maintenance of clothing, equipment, and quarters, map reading, supply, Army administration, close order drill, and physical training. Instruction in the traditions and history of the WAC was given to instill an esprit de corps in the trainees and to stress the importance of good behavior on and off duty. Before they left the training center, the newly enlisted women understood their role in the predominantly male Army and recognized that their performance in the service would be highly visible. To disgrace themselves through poor deportment or performance meant disgracing the platoon sergeants and officers who had given them their initial training. Each graduate was honored by marching in a graduation parade and receiving a certificate at a ceremony in the WAC chapel. Family and hometown friends frequently attended these festivities.

- After graduating from basic training, some enlisted women who had exhibited leadership qualities attended a special six-week course in the basic principles of leadership. This Leaders Course prepared these women and highly qualified reenlistees for responsible duty as platoon sergeants, assistant platoon sergeants, or instructors in basic or other training. In the first three weeks of classroom instruction they learned how to supervise, instruct, evaluate, and counsel other WACs. Classes included public

- [83]

-

WACS DEPART CAMP LEE after Completing basic and advanced training, December 1948.

- speaking, military history, leadership, and methods of instruction-subjects not given to basic trainees. The last three weeks of the course were spent in practical work as acting NCOs or instructors at the training center. Graduation to actual leadership positions depended upon their ability to perform these newly learned skills.

- The Officer Candidate School (OCS) accepted women who had graduated from basic training and the leaders course. Their 960 hours of instruction covered a twenty-week period. In addition to receiving further training in some of the same subjects given in basic training and the leaders course, candidates also had classes in military law and boards, food service, personnel management, methods of organization, leadership and morale, relations with civilian agencies, recruiting, military government in civil affairs, psychological warfare, and practical problems in unit management. Outstanding graduates were offered Regular Army commissions; the others received commissions in the Reserve and signed a commitment to serve a minimum of two years' active duty. Some officer candidates who wanted but did not receive Regular Army commissions on graduation from OCS embarked on a competitive tour for one year. Each woman spent four months at each of three different posts undertaking various assignments. At the end of the year, those who received high efficiency ratings from all their rating officers were offered commissions.

- Other graduates of basic training entered specialist training companies. Some received eight weeks of training as clerk typists, supply clerks, or

- [84]

- general clerks; some attended the Cooks and Bakers Course at the Quartermaster's School; some, the Stenography Course at The Adjutant General's School.

- Reenlistees arriving at the training center received initial in-processing, new uniforms, and a few refresher courses in military customs and courtesies, drills and ceremonies, and care of the uniform. At the end of two weeks, they were assigned to duty at the training center or to a WAC detachment in the field.

- Despite the strides made by women in the armed services, racial segregation remained a major issue for the Army. In 1946, the Army had made the changes in its racial policies that improved job and educational opportunities for blacks, eliminated all-black divisions, and banned some discriminatory practices, such as designation of race on overseas orders and segregation in national cemeteries. Despite the changes, however, entry quotas and segregation remained. Blacks continued to enter the Army under a quota system and to receive basic training in segregated units. OCS and specialist training were integrated, but after completing this education, blacks faced Army careers in segregated work assignments, housing, eating arrangements, and social gatherings. The new racial policies, however, provided some hope that the quotas and segregation eventually would be eliminated. 53

- The WAC reentry (reenlistment) program of 1946-1947 had been open to black women, but its primary attraction-overseas assignment-was not. When asked about this situation, Colonel Boyce stated the War Department policy: "While there is no current or foreseeable requirement for Negro WACs in any overseas theater, the question of future employment of Negro units in the overseas service is under continuing study in the War Department." 54

- After World War II, black WAC strength had declined drastically. At the end of June 1948, the month the women's Regular Army and Reserve integration bill was signed, 4 black WAC officers and 121 enlisted women remained on duty, including those serving in the Army Air Forces.55 Then on 26 July 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order No. 9981, mandating an end to racial discrimination and segregation in the armed forces. The Truman administration formed an executive commit-

- [85]

- tee, headed by Charles O. Fahey, to prepare and submit a plan for desegregating the services. Almost two years elapsed, however, before he Fahey Committee presented its final report. And, in the interim, the MAC had to follow established Army policy concerning recruitment, raining, and assignment of black personnel.

- When the WAC Training Center opened in October 1948, the 10 percent quota for black women resulted in recruiters' sending black enlistees to the center only during every fifth increment. When these women arrived at the center, they went to Company B, 1st Battalion, for Basic training; the other companies-A, C, D, and E-trained only white women. Company B, staffed with black women officers and noncommissioned officers, followed the same curriculum, techniques of training, and policies as the other basic training companies. When a thirteen-week basic raining program was adopted in the fall of 1949, every seventh increment arriving at the training center was an all-black unit, trained in Company B.

- After months of stormy meetings, maneuvering, and compromises, the whey Committee and the Army finally agreed upon a revised policy for including blacks in the Army. In January 1950, a new directive, "Utilization of Negro Manpower in the Army," was issued; it did not continue he policies of the 10 percent racial recruiting quotas, segregated basic raining, or black cadre for black units. It directed that all specialist raining courses be open to qualified blacks without quotas. Graduates of he courses were to be assigned "to any Table of Distribution or Table of Organization and Equipment unit without regard to race or color." Two months later, the Army issued a directive, effective 1 April 1950, incorporating these policy changes and eliminating racial recruiting quotas.56

- Elimination of the quota did not eliminate segregation for men; the firmed Forces Examining Stations CAFES) continued to send black male recruits for basic training only to Fort Ord and Fort Dix. But elimination )f the quota did end segregation for the WAC. Thereafter, race was disregarded for women recruits, and black and white women arriving at :he training center filled whatever unit was processing at the time. They Began side-by-side basic training in April 1950. Approval of the new policy was obvious from a comment in the center's historical report for :he quarter: "We noted the change in the Army's system of segregation as me welcomed the last Company B into 405 School [WAC Clerical Training Course for MOS 405, Clerk-Typist]." 57

- [86]

- By the end of June 1950, the WAC had been permanently integrated into the Regular Army and Reserve. The director was secure in her role as adviser to the Army staff, and her responsibilities and position gave her influence that was greater than her real authority. She also possessed an enviable latticework of communications that extended upward to the Department of Defense, through the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services, and downward to the enlisted women, through the WAC staff advisers. At the Department of the Army staff level, the WAC had senior officers in almost every General Staff and Special Staff division, who were gaining experience to assume greater responsibilities later. And although the WAC Training Center lacked elegance, it did provide command and staff leadership positions not available to WAC officers and NCOs elsewhere in the Army. The all-WAC staff at the center provided sound training, strict discipline, and patriotic inspiration for prospective officers and enlisted women, black or white.

| Unit(s) | Maximum Strength | Course Length | Input Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 Basic Training Companies | 760 | 8 weeks | 152 every 2 weeks |

| 1 Reenlistment Company | 76 | Processing | As received |

| 1 Leader's Company | 120 | 6 weeks | 20 every week |

| 3 Specialist Training Companies | 456 | 8 weeks | 92 every 2 weeks |

| 1 Officer Candidate School | 75 | 6 months | 75 every 6 months |

| 1 Reserve Basic Training | 60 | 2 weeks | 2 sessions a year |