Chapter

IV

The Korean War Era

In the early morning hours

of 25 June 1950, the army of Communist North Korea crossed the 38th Parallel

and invaded South Korea. The Communists ignored an appeal from the United

Nations for a cease-fire; the U.N. Security Council appointed the President

of the United States as its executive agent to restore peace in Korea with

the assistance of other U.N. members; and President Harry S. Truman immediately

appointed his senior military officer in the Far East, General of the Army

Douglas MacArthur, as commander in chief of the United Nations Command (CINCUNC).

During July and August, the North Korean

Army drove the U.N. forces down the peninsula. The drive was checked before Pusan,

the southernmost port in Korea. By September, General MacArthur had gathered sufficient

troop strength and firepower to drive the invaders back up the peninsula to the

Manchurian border. In late November, the U.N. forces stopped at the Yalu. The

Chinese Red Army crossed over and with the North Koreans mounted a strong offensive

that resulted in their recapturing territory down to and south of the 38th Parallel

in January 1951. A U.N. counteroffensive stopped the drive, but the entry of the

Chinese into the war removed any hope for a quick U.N. victory. The United States

and other U.N. members had to prepare to fight a longer war than they had anticipated.

Congress had already passed the laws

necessary to mobilize U.S. forces as part of the U.N. effort. In December 1950,

as the Chinese streamed south, President Truman had issued a much-delayed proclamation

that a state of emergency existed.1

By the end of January 1951, the Communist forces had been pushed back to the

38th Parallel. In April, Truman relieved MacArthur as CINCUNC and named General

Matthew B. Ridgway as the new commander. The combatants soon reached a stalemate.

In July, peace negotiations were begun at Kaesong. In August, they were broken

off, and, in October, they were resumed, at Panmunjom. An armistice was

signed on 27 July 1953.

[89]

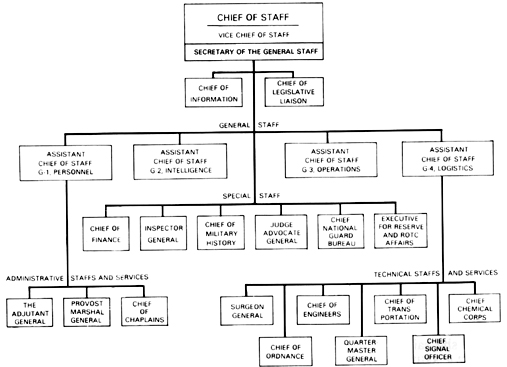

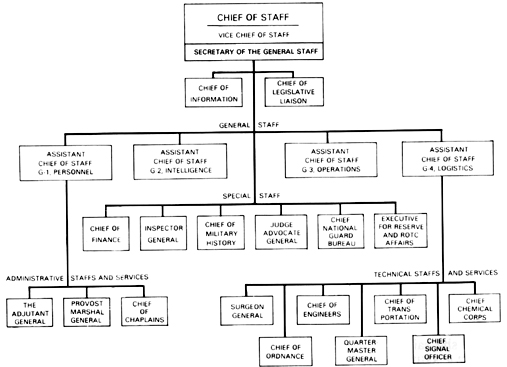

CHART 2- ARMY STAFF, ORGANIZATION, 1946

Source: WD Circular No. 138, 14

May 46.

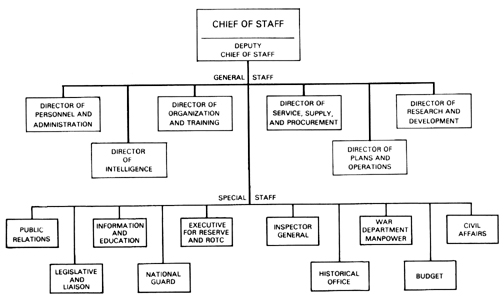

The Army had completed a major reorganization

just before the Korean War began. Under the new plan, the Office of the Director,

Personnel and Administration (D/PAD), was retitled the Office of the Assistant

Chief of Staff, G-1 (ACofS, G-1), and given the manpower control function formerly

under the director of organization and training, whose office was eliminated.

The Office of the Director, Plans and Operations, retitled Office of the Assistant

Chief of Staff, G-3 (ACofS, G-3), retained responsibility for mobilization planning

and training policies. Training supervision remained with the chief of the Army

Field Forces.2

The president and Congress had reacted

quickly to the crisis in Korea by mobilizing U.S. forces. The Army's authorized

strength increased from 630,000, when the war began, to 1,263,000 by 31 December

1950. Other measures were taken to sustain that strength:

-The president was authorized to extend

enlistment contracts involuntarily for men and women in all components and

services (PL 624, 81st Congress, 27 Jul 50).

[90]

CHART 2- ARMY STAFF, ORGANIZATION, 1950

Source: SR 10-5-1, 11 Apr. 50.

-The draft law was extended for one

year beginning 1 July 1950 (PL 599, 81st Congress, 30 Jun 50).

-The president was authorized

to order members of the Army Reserve and National Guard to active duty with

or without their consent in units or as individuals for a term not to exceed

21 months (PL 599, 81st Congress, 30 Jun 50).

The measure extending the draft had no

effect on the WAC because Congress had excluded women from registration and

induction. The measure extending enlistments, however, did affect them. It extended

for 12 months enlistments scheduled to expire before 9 July 1951. Coincidentally,

this date was exactly three years and one day after the first date when WACs

had been allowed to enlist in the Regular Army. Therefore, women who had competed

so fiercely to be "first" to enlist on 8 July 1948 were some of those

"caught" by the first of several involuntary extensions. The next

extension, ordered in July 1951, again stretched enlistments for 12 months,

until 1 July 1952; the last, ordered in April

[91]

1952, extended enlistments for 9 months,

until 1 July 1953. The last two extensions affected most of the WACs on active

duty, but no enlistment was extended involuntarily more than once.3

The third measure affected WAC reservists. They were recalled, voluntarily and

involuntarily, to serve on active duty during the war.

To maintain personnel strength at overseas

stations, the chief of staff used his regulatory authority to extend the length

of foreign service tours for six months, effective 31 August 1950. In January

1951, he again extended those tours for another six months. As a result, over

1,400 WAC officers and enlisted women had their foreign service tours lengthened-4

In November 1950, the president asked

Congress for a new draft law to replace the one that would expire on 30 June

1951. The proposal sparked a flurry of interest in registering and drafting

women. Colonel Hallaren had suggested such a measure in August. In a memorandum

to the G-1, General Brooks, she wrote: "This has been my theme song for

two years-the need for Selective Service for women (with national service) in

any future war effort. It will take a total emergency to put this through-and

it will take this to put a total emergency through." 5

Another advocate was the former director

of the WAVES, Capt. Mildred McAfee Horton. She favored drafting women in both

war and peacetime but would limit combat training and assignments to men. "It

was," she said, "more efficient to deal with one sex under combat

conditions."6

Millicent Carey McIntosh, the dean of women at Barnard College, recommended

that women register voluntarily for military service. The World War II head

of the Coast Guard's SPARS, Capt. Dorothy C. Stratton, urged compulsory registration

of women-the services would then know how many women would be available to them

for long-range planning purposes. The National Federation of Business and Professional

Women's Clubs supported drafting women. Maj. Gen. Lewis B. Hershey, head of

the Selective Service System, thought a draft of women "was possible."

Many, however, were opposed. Dr. Harold Taylor, president of Sarah Lawrence

College, felt that drafting women would "threaten our whole social structure."7

Vivien Kellems, a well-known industrialist from Connecticut, thought the patriotism

of women would bring adequate numbers of volunteers. "As to the draft

of women, I say no, it won't be necessary." 8

[92]

In any event, such measures were not

enacted. An annex to the Army's Mobilization Plan (AMP) outlined the steps to

be taken to increase WAC strength in the event of war or national emergency.

Under the plan, the assistant chief of staff, G-3, would estimate the number

of WACs needed after M-Day (Mobilization Day) for assignment to each of the

CONUS armies and the overseas theaters of war. The estimates would be passed

to the G-1 to be translated into a WAC recruiting objective for the Army Recruiting

Service and to the chief of Army Field Forces to increase basic, officer candidate,

and specialist training facilities at the WAC Training Center. "Discharge

on marriage"-marriage as an accepted reason to request and obtain an early

discharge would no longer be an option for WAC officers and enlisted women.

The training center would temporarily increase its housing and classroom capacities

by double-decking beds in the barracks and initiating a twoshift schedule of

classes. Additional WAC cadre and instructors would be obtained through recall

of WAC reservists. A new WAC training center would be opened if necessary.9

The Korean War brought about implementation

of the WAC section of the mobilization plan. Pending development of a longer-range

plan, the chief of staff approved a DWAC proposal to increase WAC enlisted strength

from 8,000 to 10,000 by 31 December. Additional WAC recruiters were sent to

the field with a new monthly objective-638, up from 324. On 25 August, the Army

suspended discharge on marriage for WAC officers and enlisted personnel.10

While the interim measures were being

taken, Colonel Hallaren developed a long-range expansion plan, which the chief

of staff approved in January 1951. The plan called for 1,000 WAC officers and

12,000 enlisted women by 30 June 1951, and 1,900 and 30,000, respectively, by

30 June 1952. To meet the strength goal for 30 June 1951, the WAC, with 240

WAC recruiters authorized, increased its recruiting goal from 638 a month to

840. To house and provide basic training for the projected increased numbers

of recruits, without establishing another training center, the WAC discontinued

the Typing and Administration Course at the WAC Training Center in mid-November

1950. Graduates of WAC basic training who were scheduled to attend the course

were diverted to similar courses at male training centers.11

[93]

The action to extend enlistment contracts

and overseas tours did not immediately increase the Army's strength. In September

1950, for the first time since January 1949, men were drafted into the Army.

But the new draftees could not be considered in the trained strength numbers

until January 1951, after they had completed a minimum of sixteen weeks' combat

training. To obtain the trained personnel it needed immediately, n July the

Army had appealed to enlisted reservists, men and women, to voluntarily return

to active duty for one year or until the emergency ended. The initial call had

been for antiaircraft gunners, mechanics, radio Operators, X-ray technicians,

translators, and stenographers. Within a few weeks, however, enlisted volunteers

in any MOS were accepted. Also, reserve lieutenants and captains in any MOS

were asked to return voluntarily to active duty. 12

The call for volunteers did not bring

in the great numbers needed, and he Army was forced to order reservists to serve

on active duty involuntarily for not more than twenty-one months. In addition

to providing troops for Korea, the United States also had to maintain and increase

its forces in Europe to deter further Soviet encroachment there. In early august,

the Army ordered 62,000 enlisted reservists to report on active duty in September

and October. Reservists assigned to units that participated in regular drill

sessions were exempt from recall. The exemption paused public protest. Inactive

reservists charged that the Army was punishing them for not participating actively

in the reserve program. army spokesmen denied the charge; the active Army reserve

units constituted the trained defense force that would be needed if the Korean

War Broadened into World War III. Despite the Army's explanations, Congress

called for an investigation, and in late October, to satisfy Congress, he Army

discontinued the involuntary recall of enlisted reservists based m the anticipated

input from the draft.13

Initially, women in the Army (WAC, Army

Nurse Corps, and Women's Medical Specialist Corps) were not included in the

involuntary recall actions. By mid-August, however, Colonel Hallaren had recognized

;he need for additional women to fill future requirements. On 25 August, :he

G-1, Lt. Gen. Edward H. Brooks, who had replaced General Paul on l January 1949,

approved her request to prepare, with the chiefs of the army Nurse Corps and

Women's Medical Specialist Corps, a combined plan for women. The chief of staff

approved their plan on 21 September. But, since involuntary recall of enlisted

reservists was ended in October, :he plan affected primarily the officers of

those corps.14

[94]

To carry out the recall plan, the commanders

of the CONUS armies received monthly quotas for reserve officers and selected

those to be recalled. The quotas were filled first with volunteers, then with

women from inactive units (not receiving drill pay) who were single and had

no dependents, and, in last priority, married women without dependents. Women

with children or dependents under eighteen were not involuntarily recalled.

Nurses, dietitians, or therapists who held key administrative or teaching positions

or whose departure "would jeopardize the health of the community in which

employed" were not recalled. During fiscal year (FY) 1951 (1 July 1950-30

June 1951), 67 WAC officers and 1,526 enlisted women were voluntarily recalled

on active duty; 175 WAC officers were involuntarily recalled. 15

Though not subject to the draft, active

duty and reserve WACs were subject to every other mobilization measure. The

involuntary recall of reserve officers in 1951 marked the first time women were

summoned on active duty without their consent. Technically, they had consented

to recall by voluntarily joining the Army Reserve, an action that plainly carried

an active duty commitment in the event of war or national emergency. Nonetheless,

for women, it was a "first" worthy of note.

The controversy over mobilization practices

led the Department of Defense to examine its personnel plans and policies. One

study group was assigned to determine whether women were being underutilized.

On 12 October, the group issued its report, "A Study of the Maximum Utilization

of Military Womanpower." It recommended that the services formulate a

joint policy for the expanded employment of military women and that they study

the effect of applying policies for men to women or to mixed groups. The report

proposed research into the participation of women in the armed services; the

development of mechanical aptitude tests for women; the development of functional

clothing and safety devices for women; and the recruiting practices and positions

that the services assigned to military and civilian women.16

The services were not pleased with the

report. The assistant secretary of the Air Force stated that the Air Force mission

had to guide its utilization of women. The Air Force had studied its mobilization

requirements for women and had appointed a panel, led by famed flier Jacqueline

Cochran, to conduct a study of utilization of the WAF. The secretaries of the

Navy and Army recommended that, before any policy statements or research programs

were initiated, an interservice committee of

[95]

senior women officers draft a department-wide

policy on the utilization of women. The committee should also study the proposed

research projects and make recommendations concerning them.17

The chairman of the DOD Personnel Policy

Board agreed with the commendation, and, in February 1951, directed each of

the services to elect a senior woman officer for the committee. Lt. Col. Kathleen

McClure, deputy director of the WAF, was appointed chairman of the study group.18

Originally classified "secret,"

the 200-page report was completed on 9 April 1951 and was signed by each member

of the group. The conclusions reached by the panel were similar to the attitudes

expressed by their service chiefs on the October 1950 study. They joined the

men in rejecting the assistance offered by the DOD Personnel Policy Board in

what hey considered their services' internal policies. The women directors had

jealously guarded their role as experts on matters affecting military women.

They recommended that no action be taken on the recommendations in the October

study. They further concluded that existing laws, regulations, policies, and

directives concerning women did not adversely effect their utilization by the

military services: "since the Services are working continuously on a refinement

of these criteria and are constantly -valuating their utilization of military

womanpower in terms of occupational studies and experience, no further clarifying

policy or directives . . . are needed to assure efficient utilization of military

womanpower."19

The DOD Personnel Policy Board accepted the report without comment.

While the women officers were formulating

their report, Margaret Mase Smith, now a member of the Senate, asked for the

plans for utilizing women in the event of total mobilization and for an estimate

of .he extent to which women would replace men. Under Secretary of the Navy

Dan A. Kimball stated that, under total mobilization, women could replace up

to 15 percent of the Navy officers and 12 percent of the :misted men and up

to 7 percent of Marine Corps officers and enlisted men. Assistant Secretary

of the Air Force Eugene M. Zuckert replied :hat women could replace approximately

10 percent of its men. Assistant Secretary of the Army Earl D. Johnson reported

that the Army would provide for the "replacement of male personnel by WAC's

to the maximum extent." This would, he said, require some form of involuntary

[96]

induction for women. "In this connection,

there is presently being processed within the Department of the Army, a draft

bill to make Standby Selective Service Legislation applicable to women as well

as to men in time of full mobilization."20

The draft bill referred to by Secretary Johnson did not get far. The DOD Personnel

Policy Board failed to show any interest in the proposal, and General Brooks,

the G-1, shelved it.21

Beginning in 1948, the Organized Reserve

Corps (ORC) had welcomed WAC members into the various established units and

branches. In fact, WAC staff advisers reported that "the demand for WAC

reservists exceeds the supply."22

And, while WAC participation rose from zero in June 1948 to 4,281 in 1950, it

was far short of the 20,000 ORC spaces the Army had hoped the WAC would fi11.23

The Korean War recall programs revealed

weaknesses in the readiness of the ORC-outdated personnel rosters, incomplete

training and qualification records, physically unqualified personnel. Reservists

failed to notify their units when they moved, enrolled in college, or voluntarily

returned to active duty. Complicating matters for the WAC, women reservists

also failed to report marriages, changes in name, births of children, or the

addition of other dependents. And compounding the problems for the entire Army,

annual physical exams for officers had been discontinued in February 1947 for

lack of funds.

In October 1950, to correct these problems,

which affected each of the services, George C. Marshall, now secretary of defense,

directed that the armed forces screen their reserve personnel records and correct

them; reject any unfit reservists; and code the availability status, in days,

for each member. In the latter process, each eligible reservist, male or female,

was placed in a mobilization category representing the number of days that the

reservist had between notification of recall and reporting for active duty.

The category, or amount of time given, was based on the reservist's occupation,

complexity of personal affairs, number of dependents, and physical status. Two

years later the Armed Forces Reserve Act of 1952 abolished this cumbersome system

and assigned readiness catego-

[97]

ries to units rather than individuals.

This law also redesignated the Organized Reserve Corps as the United States

Army Reserve (USAR).24

As a result of the Korean mobilization

experience, the USAR changed enlistment and reenlistment qualifications for

WAC reservists to coincide as closely as possible with those for Regular Army

WAC personnel. Few changes, however, were made in utilization or training policies

for the reservists. Screening, discharge regulations, and recall programs reduced

the number of WAC reservists from 4,281 on 30 June 1950 to 2,524 on 30 June

1951.25

On 9 January 1951, General Brooks advised

Colonel Hallaren and the chief of the Military Personnel Procurement Services

Division (MPPSD) that Colonel Hallaren's plan had been accepted and that the

WAC target strength for 30 June 1952 was 30,000 enlisted women-2 percent of

the 1.5 million-man Army authorized by Congress. The WAC goal for 30 June 1951

remained at 17,000 enlisted women .26

As of 1 January, however, the WAC had

only 8,674 women on duty; the short-term goal of 10,000, set in August, had

not been reached. WAC strength had to double in six months to meet the new goal.

The number of WAC recruiters was increased from 90 to 240; a shorter, two-year

enlistment period was added; and recruit application procedures were streamlined.

For the first time since 1945, the Army purchased advertising time on radio

and television for WAC recruiting and funded the publication of additional promotional

literature and posters. Colonel Hallaren also recommended a joint male-female

recruiting campaign to spur enlistments. "The WAC objective will not be

reached," she warned, "until every . . . procurement speech made by

Army personnel includes the need for both men and women . . . and until publicity

pictures include women and men." 27

However, the Army's recruiting theme for 1951, "The Mark of a Man,"

was already under way and did not lend itself to including women. Nonetheless,

several recruiting posters were produced showing men and women serving together.

The chief of the MPPSD recommended that

controlled input (i.e., a quota given each CONUS army) into the WAC Training

Center be abandoned so that a recruiter would not be limited to the weekly quota

and could send as many enlistees as possible after their applications had been

approved. Upon the recommendation of the new WAC Training

[98]

Center commander, Lt. Col. Ruby E. Herman,

Colonel Hallaren vetoed this idea because the center did not have barracks space

to "store" new recruits until their training began. Colonel Hallaren,

however, did agree to reconsider the idea if the WAC recruiting objective were

to be greatly increased in the next six months; and the training center was

alerted to plan for this contingency.

With exceptional performance by the

WAC recruiters, from the start of the war to 30 June 1951, WAC strength increased

by a little over 60 percent. Enlisted strength, however, was still a little

over 6,000 short of the goal of 17,000. During the period from 30 June to 31

December 1950, 3,603 enlisted women had entered the Corps (including 1,140 recalled

reservists); between January and June 1951, 3,443 had entered (including 385

recalled .reservists). Total WAC strength on 30 June was 11,932.28

WAC recruiting appeared to be repeating

the pattern that had emerged during World War II. At the outbreak of the war,

women had rushed to enlist, but as the war wore on, enlistments fell off. There

were, however, contributing factors. Between January and June 1951, the new

recruiters and promotional brochures trickled slowly into the recruiting stations.

And, once on duty, the new recruiters, untrained and inexperienced, had to learn

their sales techniques on the job. Finally, the large number of high school

graduates who usually were ready to enlist in May and June simply did not materialize.

Army enlistments, male and female, declined during these months. (See Table

4. )

| |

Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

| WAC Enlistments |

694 |

614 |

733 |

543 |

415 |

444 |

| Male Enlistments |

35,327 |

27,355 |

23,710 |

16,587 |

10,058 |

10,829 |

Source: Strength of the Army Report

(STM-30), 31 Dec 53.

Despite recruiting problems, the overall

strength in each of the women's services had increased impressively during fiscal

year 1951. (See Table 5.)

The increase interested Anna M. Rosenberg,

Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Personnel. She believed it showed

great potential for increasing military womenpower.

[99]

Women know that they have a stake in

this nation. During World War II, the women exercised the right to serve on

equal terms with men as they volunteered in large numbers in the WAC, the WAVES,

the SPARS, the Women Marines, the Nursing Services, and Medical Specialists

Corps. Now with an acute shortage in manpower, women again have the opportunity

of serving. They will not be found wanting.29

| Service |

30 June 1950 |

30 June 1951 |

| WAC |

6,551 |

10,883 |

| WAVES |

2,746 |

5,268 |

| WAF |

3,782 |

7,514 |

| Women Marines |

535 |

2,002 |

| Total |

13,614 |

25,667 |

Source: Semi-Annual Report of the

Secretary of Defense, Jan 1-Jun 30, 1951 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1951), p. 22.

Mrs. Rosenberg set out to obtain 72,000

more servicewomen and began by asking Congress to remove the 2 percent ceiling

on the strength of women in the regular forces. Congress complied, suspending

the ceiling until 31 July 1954 (PL 51, 82d Congress, 1st session, 19 Jun 51).

Next, she presided over the first meeting of the Defense Advisory Committee

on Women in the Services (DACOWITS) on 18 September 1951 and asked its members

to spearhead the recruiting campaign. They agreed and, with the directors of

the women's services and staff officers in the Department of Defense and the

three services, developed a "Unified Recruiting Plan" to begin on

11 November 1951.

The basic work of the campaign began

in committee members' home communities. Those on the committee who were college

presidents invited service recruiters to their campuses to talk to students

about a military career after graduation. Presidents of women's clubs asked

their chapter members to invite recruiters to speak to audiences in civic, church,

or school organizations. The journalists, broadcasters, and publishers among

the group used their media to tell women about the need for and the benefits

of service life for women; Helen Hayes and Irene Dunne, noted stage and screen

actresses, gave interviews on the need for women in the armed forces. Some women

convinced the governors of their states to issue proclamations on the need for

women in the services. Others pushed members of Congress to approve a commemorative

stamp honoring women in the services, and, on 11 September 1952, President Truman

[100]

presided over the first-day-of-issue

ceremony at the White House.

President Truman had officially opened

the recruiting campaign by announcing it in his annual Armistice Day speech

delivered by radio on 11 November 1951. He told his listeners: "There are

now 40,000 women on active duty in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines. In

the next seven months we hope at least 72,000 more will volunteer for service.

Our Armed Forces need these women. They need them badly. They need them to undertake

every type of work except duty in actual combat formations." 30

Detachments of servicewomen buttressed

the initial effort as they marched in Armistice Day parades in New York City,

Chicago, San Francisco, Atlanta, and other cities. Throughout the year, nationally

known people assisted the Department of Defense in promoting the campaign. Generals,

admirals, and high-ranking civilian government officials publicly praised the

contributions of military women and described the need for them. The National

Advertising Council prepared and distributed thousands of newspaper ads, outdoor

advertising signs, bumper stickers, and fact sheets to over 1,500 newspapers,

magazines, and other media outlets as a public service to enhance the recruiting

campaign. The theme was "Share Service for Freedom."

To reach the goal set by Mrs. Rosenberg,

the WAC had to recruit 20,000 women by June 1952. The Army increased the WAC

recruiting objective to 2,400 a month and increased the number of WAC recruiters

to 486. Statistically, each recruiter had to enlist 5.2 recruits a month to

achieve that goal. Colonel Hallaren, in a move agreed to by Colonel Herman,

relinquished controlled input of trainees at the WAC Training Center to eliminate

a factor the recruiters said was an obstacle to their success. Other changes

at the center included a switch to the committee system of instruction in October

1951 and introduction of two-level training in March 1952.

The women's basic training program,

like the men's, had been reduced in length in October 1950 from 13 to 8 weeks.

Until October 1951, unit cadre conducted all basic training courses, but under

the committee system, officers and NCOs from the office of the S-3, WAC Training

Center, conducted 35 percent of the training to free the cadre for other duties.

With two-level training, a basic training company would begin one class as soon

as one or two platoons filled and would begin another when the other platoons

filled the company a week later.31

[101]

In November 1951, Mrs. Rosenberg visited

the troops in Korea and Japan. Upon returning, she announced, "A WAC unit

of 600 members will be sent to fill jobs at the United States Eighth Army supply

base in Pusan, Korea." 32

In other years such an announcement of opportunity for foreign service duty

would have created `a flood of applicants for WAC enlistment at recruiting stations.

But, a month later, Colonel Hallaren was forced to tell newsmen that "the

lag in recruiting" forced the Army to postpone, indefinitely, assignment

of a WAC unit to Korea.33

Colonel Hallaren's words provided an

early indication that all was not going well with the Unified Recruiting Campaign.

Despite increased publicity, advertising, and recruiters, WAC recruitment for

FY 1952 did not equal that achieved during FY 1951-7,046 enlisted women and

423 commissioned and warrant officers. In FY 1952, the Corps gained only 3,933

enlisted women and 330 officers; attrition, however, doubled .34

After discharge on marriage had been

discontinued in all services in August 1950, losses resulting from pregnancy

climbed sharply, exceeding even the high rate anticipated under wartime conditions.

Women were using discharge on pregnancy to break their enlistment contracts

in order to establish households with their husbands, or, sometimes, to leave

the service when they became dissatisfied. WAC leaders reasoned that the pregnancy

rate would climb higher if discharge on marriage were not reinstated, and it

appeared to be a benign action since truce talks had begun. Discharge on marriage

was reinstated on 20 July 1951 for enlisted women in all services and much later,

on 18 September 1953, for women officers. Unfortunately, when the decision was

made to reinstate discharge on marriage for enlisted women, no one foresaw that

a Unified Recruiting Campaign would begin in November 1951.

[By percentage of total WAC losses]

| Discharge on: |

FY 1950 |

FY 1951 |

FY 1952 |

FY 1953 |

FY 1954 |

| Marriage |

26.9 |

9.3 |

34.9 |

27.6 |

16.6 |

| Pregnancy |

18.9 |

39.5 |

23.9 |

19.0 |

14.6 |

| Total |

45.8 |

48.8 |

58.8 |

46.6 |

31.2 |

Source: Losses of Enlisted Women by

Cause, Strength of the Army Report (STM-30), for the years shown.

[102]

Thus, while the unified campaign was

in progress during FY 1952, the WAC experienced high rates of losses on marriage

and pregnancy. Those losses, with the poor recruiting results, had a severe

effect on the strength of the Corps. (See Tables 6 and 7.)

| Service |

30 June 1950 |

30 June 1951 |

Increase or Decrease |

| WAC |

11,932 |

11,456 |

-476 |

| WAVES |

6,074 |

8,167 |

+2,113 |

| WAF |

8,001 |

11,891 |

+3,890 |

| Women Marines |

2,065 |

2,462 |

+397 |

| Total |

28,072 |

33,996 |

+5924 |

Source: Selected Manpower Statistics,

Office of the Comptroller of the Department of Defense, 30 Jun 56, p. 41.

Early in the recruiting campaign, Mrs.

Rosenberg discovered that the service recruiters lacked marketing information

for their campaigns. Hence, in 1952 she directed that a comprehensive attitude

survey be conducted to discover women's reasons for enlisting and reenlisting.

Some of the findings concerning the WACs were informative:

-Four out of every ten newly enlisted

women said they entered the WAC to receive training in a skill (38 percent);

to travel (19 percent); to serve their country (18 percent); to get away from

an unsatisfactory job or home situation (10 percent).

-Of a group of 980, 30 percent said

they intended to reenlist and 24 percent were undecided. Of the 30 percent who

said they intended to reenlist, 63 percent desired an overseas assignment.

-The most frequent reasons given for

not reenlisting were marriage or pending marriage; dissatisfaction with military

job, promotion, or pay; desire to obtain more civilian education or training;

dissatisfaction with lack of acceptance of women or their perceived reputation.

-Sixty-two percent of the women felt

men and women were treated equally by the Army; 27 percent felt women were treated

better; 11 percent thought men were treated better.

-Older enlisted women in NCO grades

who held supervisory jobs or jobs requiring initiative, originality, or responsibility

were most likely to reenlist.35

[103]

The studies, conducted in 1952 and 1953,

provided information that would be of future value to enlistment and reenlistment

planners for the WAC and the other women's services.

Colonel Hallaren had her own thoughts

about why the WAC recruitment effort had failed during 1952. At the Personnel

Officers Conference at the Pentagon in December 1952 as her term as director

of the WAC drew to a close, she said that the Unified Recruiting Campaign "could

hardly be considered an unqualified success." She attributed the failure

of recruitment to "inexperience of women recruiters; parental objection;

poor reputation of service women; and competition with civilian industry."

In addition, she blamed competition with the Air Force.36

She also offered some constructive suggestions

to improve WAC recruiting. She recommended that enlisted recruiters be replaced

on a "one WAC officer for two enlisted women basis." She observed

that the average enlisted recruiter did not have the schooling, the background,

or the pay to be a supersalesman and compete "with high powered civilian

procurement agencies" or with women in the Air Force who somehow received

promotions faster than the WACs. "It is no reflection on a WAC corporal

that she has a difficult time selling a career in the Army when the WAF she

recruited last year comes home with three stripes while she still has two."

37

Colonel Hallaren believed that parental objections to women joining the WAC

were frequently based on "war stories" about WACs. When traced to

their sources, the stories proved to be invented or embellished beyond recognition.

To help eliminate these myths and stories, she suggested that accurate information

could improve the recruiting problem. "If representative high school students,

teachers, and parents were invited to visit the WAC units in their areas, familiarity

would breed content." 38

Like many Army officers concerned with

recruiting, Colonel Hallaren disliked the joint Army-Air Force recruiting system.

Under it, shared office space put recruiters in direct day-to-day competition

in a single place where they could scrutinize each other's prospects and listen

to each other's sales techniques. The Army could not compete with the "wild

blue yonder" image, the glamour of the Air Force. As the 1950s progressed

WAF recruiters increasingly outsold their WAC counterparts, even though WAC

entry requirements seemed easier. The WAC would accept women for a two-year

rather than a three- or four-year enlistment; women with General Educational

Development (GED) certificates in-

[104]

| ANNA M. ROSENBERG,

Assistant Secretary of Defense, Manpower and Personnel (1950-1953). |

|

GENERAL J. LAWTON

COLLINS, Army Chief of Staff (1949-1953). |

stead of high school diplomas; and women

with slightly lower intelligence test scores.39

Colonel Hallaren opposed adopting the

WAF standard of accepting only women who scored in the top two (of four) mental

aptitude categories. The WAC accepted women in the top of the third category,

slightly below the median in intelligence. The director was a staunch supporter

of the concept of "quality before quantity," but she saw no reason

to enlist women who were overqualified for the jobs they would be doing. She

recommended that greater emphasis be placed on good character and an unblemished

record of deportment. Women with a very high intellect would, she felt, become

bored and discontented in many jobs available to them in the Army.

We cannot go along with raising the

AFWST [Armed Forces Women's Selection Test] score to the 65th percentile. There

are jobs to be done in the clerical, medical, food service, and other fields,

in the Air Force as well as the Army,

[105]

which [would bore] an individual with

a high IQ . . . into non-reenlistment. Chew jobs must be done. In an emergency

we would have many such assignments.40

WAC recruitment had been successful

early in the Korean War; then accessions declined. After July 1951, the unpopularity

of the war, the dart of truce talks, the competition with the other women's

services for recruits, and public apathy combined to cut WAC enlistments in

half. the Unified Recruiting Campaign, begun with such high hopes in November

1951, proved unsuccessful as that fiscal year drew to a close in tune 1952.

Fiscal year 1953 was equally unsuccessful. Recruitment of males also dropped,

from 238,000 in FY 1951 to 155,000 in FY 1953. army strength was maintained

through the draft (1.5 million men) and recall from the reserve components (288,000

reservists and guardsmen).41

The war in Korea reinforced the change

in the mission of U.S. military forces around the world from occupation to defense

against invasion. No one knew what the Russians would do while the United States

was preoccupied by the Korean War. According to one historian, James F. Schnabel,

"The United States believed Russia to be the real aggressor in Korea, in

spirit if not in fact, and effective measures to halt the aggression night provoke

total war . . . . The determinant for Korea was, then as always, 'What will

Russia do? 42

In addition to forces fighting in Korea, North Atlantic Treaty Organization

(NATO) obligations required ;he maintenance and reinforcement of Western defenses

in Europe, while ether treaty commitments required the defense of Japan and

the Ryukyus. During FY 1951, the United States sent twelve additional combat

divisions to Korea, Japan, and Okinawa and four to Germany.

WAC strength overseas fluctuated with

the Korean War. At the start A the conflict, approximately 20 percent of WAC

strength was overseas; ;hat percentage increased during the second year, then

fell after the war ended. (See Table 8. )

In Japan, WAC strength increased rapidly

after the war began. In July 1950, the WAC had two detachments, at Tokyo and

at Yokohama; by mid-1951, there were six; and by the end of December 1953, there

were Zine.43

A WAC unit was also established at Fort Buckner on the island )f Okinawa in

1951.

[106]

| |

1950 |

1951 |

1952 |

1953 |

1954 |

| Far East |

626 |

2,604 |

1,791 |

1,764 |

976 |

| Europe |

632 |

933 |

1,356 |

1,130 |

994 |

| Australia |

84 |

81 |

139 |

143 |

74 |

| Caribbean |

91 |

98 |

89 |

89 |

1 |

| Total |

1,433 |

3,716 |

3,375 |

3,126 |

2,045 |

Source: Strength of the Army Report

(STM-30), for 30 June of each year noted.

The women in these units, both officers

and enlisted, were assigned primarily to administrative, communications, medical,

and intelligence duties. They worked at Far East Command headquarters and other

commands in Tokyo, at regional commands throughout Japan, and at general and

station hospitals in Japan and Okinawa.

In the first year of the war, the shortage

of personnel in some specialties was critical. Overseas, women who held one

essential MOS were often retrained in an even more urgently needed MOS-telephone

and teletype operators, cashiers, motor vehicle operators, mechanics, and medical

corpsmen. Without complaint, the WACs did their best at whatever work needed

to be done. At the May 1951 WAC Staff Advisers Conference, Lt. Col. F. Marie

Clark, the adviser for the Far East, reported: "As a result of the Korean

situation, WACs in the Far East Command are being efficiently utilized in assignments

heretofore believed by some could only be performed by male personnel .... With

few exceptions, WACs arriving subsequent to June 1950 have been and are being

utilized in positions either to replace or release a man to a combat element."

44

One landmark in the utilization of medical

WACs occurred in the Army hospitals in Japan. As a matter of necessity, WACs

had been assigned as wardmasters, a supervisory role traditionally the province

of male medical NCOs. The medical WACs also learned specialized skills by assisting

in the care of paraplegics, victims of frostbite, and patients with broken or

injured limbs, hepatitis, and other injuries and illnesses. The Chief, Army

Nurse Corps, Col. Mary G. Phillips, praised their work. "We have found

wherever we have WAC technicians in our hospitals that, on the whole, they are

doing a wonderful job. There are, however, too few of them. Many, after putting

in long hours of work in their assigned duty, volunteered their services for

extra duty or visited the

[107]

patients after working hours to take

care of personal needs such as letter writing, post exchange purchases, etc.

"45

By the spring of 1951, while over 300'Army

nurses were in Korea at field, station, evacuation, and mobile Army surgical

hospitals, WACs waited expectantly for a detachment of their own to be formed

for service there. Months passed, but, even though more and more WACs were requisitioned

for duty in Japan and Okinawa, no detachments were requested for Korea. During

the WAC Staff Advisers Conference in day, the G-1, Lt. Gen. Edward H. Brooks,

said, "I just came back from Korea and I believe there is a real requirement

over there for women in uniform-WACs and WAVES." 46

His words swept through the Corps, gut no detachments were assigned. In August,

Lt. Gen. Anthony G. McAuliffe succeeded General Brooks as G-1; still no WAC

detachments were assigned. A year later, in August 1952, General Mark W. Clark,

then commander in chief of the United Nations Command and Far East Zommand,

asked General McAuliffe whether women could be assigned to Korea. The

G-1 replied that policy allowed it, but that WAC recruiting, was poor-no further

WAC units could be sent to the Far East. Thus, even though individual WACs would

serve in Korea on special assignments, the door was closed to the establishment

of a WAC unit in Korea. 47

Despite the fact that no WAC units were

assigned to Korea, contact was established with the Corps' counterpart in the

Republic of Korea ROK) Army. Its women's corps had formed rapidly in 1950 around

a nucleus of policewomen trained for service in the Korean National Constabulary

in 1946 by a former WAC captain, Alice A. Parrish, who, in 1948, rejoined the

WAC and remained in the Regular Army until retirement. Contact during the war

strengthened the tie and led to the assignment of a senior WAC officer as U.S.

military adviser to the ROK Army WAC in 1956; the position was not discontinued

until 1974.48

Ending the war in Korea became a major

issue in the 1952 presidential campaign. In November, Dwight D. Eisenhower was

elected; in January 1953, he was inaugurated. In March, Joseph Stalin died;

he was succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev. Negotiations at Panmunjom accelerated.

In

[108]

July, an armistice was signed. No massive

demobilization followed the end of the war in Korea. By December 1952, most

of the recalled reservists had been released from active duty and had been replaced

by draftees or Regular Army personnel. Draft calls had already fallen from a

monthly high of 87,000 in January 1951 to 26,000 in July 1953. At the time the

armistice was signed, the Army had only 1.5 million men and women on active

duty. No demobilization plan was needed-the men and women left the Army as their

terms of enlistment ended or as they were released to the Army Reserve or the

National Guard to complete the balance of their obligated federal service. Congress

rewarded Korean veterans as it had veterans from World War II-educational benefits,

home loans, mustering-out pay, reemployment rights. Those who had served in

the combat zone had received hazardous duty (combat) pay and deferment from

federal income taxes on that money.

By the end of 1952, Col. Mary A. Hallaren

had completed almost six years as director of the WAC. She had led the effort

to obtain Regular Army and Reserve status for WACs. She had directed the procedures

for assimilating WACs into the regular and reserve components between 1948 and

1950; supervised the revival of WAC recruiting and the opening of the WAC Training

Center; and led the Corps through most of the Korean War. After leaving the

directorship, she served on active duty for another seven years before retiring

in 1960 at age 53.49

At Colonel Hallaren's retirement, Col. Mary Louise Milligan, then the director

of the WAC, summarized: "She had symbolized the highest traits of character

and service which I am certain General Marshall visualized when he planned for

American women to serve in our Army. It was due to her outstanding leadership

and service that our organization was made a permanent part of the Regular and

Reserve forces of our Army."50

Before her tour as director ended, Colonel

Hallaren gave the G-1, General McAuliffe, a resume on each of tile Regular Army

lieutenant colonels eligible to replace her. The list was considered by Secretary

of

[109]

the Army Frank Pace, Jr., Assistant

Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs Fred Korth, and Army

Chief of Staff J. Lawton Collins. Although there were nineteen eligible lieutenant

colonels, seniority was an important consideration in filling statutory positions,

and it was almost certain that Charlee L. Kelly, Cora M. Foster, Elizabeth C.

Smith, Dr Irene O. Galloway would be chosen. On 9 December 1952, Secretary Pace

announced the selection of Irene O. Galloway to be director of the WAC.51

Quiet-spoken and more conservative than

her predecessor, Irene Otillia Galloway had a strong personality and a reputation

for sincerity and skilled performance of duty. She had graduated with the second

WAAC OCS class, September 1942, and had served at WAAC headquarters at the Pentagon;

at Headquarters, Army Service Forces; and with the G-1 Career Management Group.

From June 1948 to October 1952 she was assigned as WAC Staff Adviser, U.S. Army

in Europe. In November, she was selected to replace the commander of the WAC

Training Center, who was resigning her commission to get married.52

Colonel Galloway reported to Fort Lee on 24 November 1952 and within two weeks

was notified she had been selected to be the new WAC director. On 3 January

1953, in Secretary Pace's office, she was sworn in as the director of the WAC

and promoted to temporary colonel.53

The position of deputy director had

officially been vacant since September 1952 when Colonel Milligan left for

Germany to relieve Colonel Galloway. Lt. Col. Charlee L. Kelly had performed

the duties without being appointed to the position by Colonel Hallaren, who

wanted her successor to be free to select her own deputy. Colonel Galloway selected

Lt. Col. Emily C. Gorman, then the WAC staff adviser at Headquarters, Second

Army, Fort George G. Meade, Maryland; she was sworn in by the adjutant general,

Maj. Gen. William E. Bergin, on 3 January 1953.54

Other positions in the Office of the

Director, WAC, were also filled: Maj. Rebecca S. Parks became the executive

officer; Maj. Catherine J. Lyons, WAC career management officer, and the only

holdover from Colonel Hallaren's staff, Maj. Elizabeth P. Hoisington, became

the technical information officer.55

[110]

Colonel Galloway assumed her duties

in 1953, a year of many changes in national and world affairs. The status of

women was also changing. President Eisenhower appointed Oveta Culp Hobby to

his cabinet as the secretary of the newly established Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare. Mary Pillsbury Lord was appointed as a U.S. representative

on the U.N. Economic and Social Council. Clare Booth Luce, a congresswoman from

Connecticut, became the first woman appointed ambassador to a major nation-Italy.

Elizabeth II, who had succeeded to the throne in 1952, was crowned Queen of

England and the British Empire on 2 June 1953, and, in September, Mrs. Vijaya

Pandit of India was elected president of the United Nations General Assembly.

There were also changes in the other

women's services. The Women Marines, with over 2,500 women on active duty, celebrated

their tenth anniversary in February 1953 and welcomed a new director, Col. Julia

E. Hamblet. Over fifty enlisted WAVES were assigned to sea duty for the first

time in 1953; they served on ships of the Military Sea Transportation Service.

Capt. Louise K. Wilde replaced Capt. Joy Bright Hancock as director of the WAVES-official

title, Assistant to the Chief of Naval Personnel for Women-on 1 June 1953. The

Air Force selected its second ex-WAVE officer to be director of the WAF, Col.

Phyllis D. S. Gray, who replaced Col. Mary Jo Shelley on 1 January 1954. Col.

Ruby F. Bryant had been appointed chief of the Army Nurse Corps in 1951 and

would serve until 1955. And in March 1953, 1st Lt. Fae M. Adams became the first

woman physician appointed to the Regular Army Medical Corps. 55

After the Korean armistice, the United

States had no time to be complacent. In August, the Soviet Union detonated a

hydrogen bomb, ending the United States' monopoly over nuclear power. The nature

of East-West friction changed. Scientific and technological competition intensified.

Weapons and weapon systems became more sophisticated. Skilled technicians became

more necessary. Standing armies grew.

Such changes also affected the WAC,

but responding was difficult. With the draft providing the requisite number

of men, Congress cut recruiting budgets. The FY 1953 budget limited those expenses

to half that spent in FY 1952. The WAC, dependent on recruiting, saw its publicity

funds cut and half of its recruiters reassigned to nonrecruiting duties.

The WAC, like the other women's services,

was now a permanent part of a large, continuing peacetime military establishment.

Improved administration and reduced costs were now the goals.

[111]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the

Table of Contents