-

The subject of WAC strength was

uppermost in Colonel Galloway's mind at her first WAC staff advisers

conference in May 1953. In her opening remarks, she outlined the

problems ahead: "The matters of primary concern to us include our

strength trends and our future procurement. We can take definite and

corrective action and build increased interest and impetus in the

matters of recruiting and reenlistment."1

Reinforcing that

concern, Brig. Gen. Herbert B. Powell, Deputy Assistant Chief of

Staff, G-1, Manpower Control, told the attendees: "I stress to

you, and urge your continued emphasis on, the need for the services of

volunteer women in the Army. The utilization of women in the Army is

an integral and carefully evaluated factor in the overall national

manpower potential .... The second consideration which I stress with

equal emphasis is the matter of reenlistments." 2

-

- For the second consecutive

year, WAC losses had exceeded gains. Recruiting and reenlistment

rates had gone downhill for both men and women beginning in June

1951 and had continued downward-a trend not totally unexpected

with an expanding wartime economy and an unpopular war. But in the

spring of 1953, peace seemed to be in sight, and it was hoped that

civilian attitudes toward military service would improve so that

recruiters could again interest young women in an enlistment or a

career in the Women's Army Corps. Such changes were needed for the

Corps to continue as a creditable manpower resource to the Army.

Colonel Galloway and her staff, unable to influence prevailing

attitudes, began examining the discharge policies on marriage,

pregnancy, and parenthood to find a way to reduce the Corps' heavy

losses in those areas.

-

-

- During most of World War

II, no policy had existed under which women could be discharged on

marriage. After V-E Day, women could request discharge when their

husbands were demobilized. Later, any

- [137]

- WAC who had married before

V-E Day could be discharged without regard to demobilization

points or to her husband's status as civilian or military. After

demobilization ended, WACs could be discharged on marriage upon

request. The policy, however, was stiffened when the WAC entered

the Regular Army in 1948. Thereafter, neither officers nor

enlisted women could be discharged on marriage unless they had

completed one year of their current enlistment or appointment

contract. This policy was included on enlistment applications so

that the women would be aware of the obligation.3

With the Korean

War, discharge on marriage had been suspended. When it was

reinstated, the eligibility requirements had again changed.

Enlisted women had to have completed one year of service beyond

their initial training and arrival at the first duty station;

officers needed two years' continuous active duty. Women stationed

overseas at the time of their request had to complete one year of

their foreign service tour in addition to attaining the basic

eligibility for discharge.4

-

- Few changes had occurred

in policy regarding discharge for pregnancy. From the days of the

Auxiliary Corps, women had been discharged as soon as possible

after a doctor had certified the condition. During World War II,

women at posts in the United States were usually processed out of

the Army within fourteen days after certification; women stationed

overseas were returned to the United States by air and then

discharged. After the war, women who were pregnant could be

discharged overseas if their husbands were there. Whether they

were married or single, women being discharged on pregnancy

received honorable discharge certificates; women who had illegal

abortions did not. Instances of the latter were rare. If women who

were to be discharged for some cause other than pregnancy

(unsuitability, demobilization, etc.) were found to be pregnant

during their final physical examination, they were discharged for

the original cause, but their discharge papers noted that they

were pregnant. This enabled them, if they had an honorable

discharge, to receive maternity care at an authorized military

facility.5

-

- During its 1948 hearings

on the WAC bill, Congress had made clear that the service should

not interfere with the accepted pattern of women's lives.

Congressman Carl Vinson stated: "We should not put anything

in

- [138]

- the law which should cause

them to hesitate getting married or to raise a family; on the

contrary, we should encourage it." 6

As a result, the WAC and

other women's services continued their World War II policies that

permitted women to marry, have children, and leave the service.

Congress stopped short of encouraging family life for women in the

service by not extending dependency allowances to the husbands or

children of military women. The law stated that "husbands of

women officers and enlisted personnel . . . and children of such

officers and enlisted personnel shall not be considered dependents

unless they are in fact dependent on their [wives or] mothers for

their chief support."7

Congress allowed dependency status to

wives and to children under eighteen whether or not they were

capable of working, but it would not automatically grant that

status to husbands, who were presumed to be capable of working to

support their wives and children.

-

- WACs had received no

maternity care until the last months of World War II. After

November 1944, women honorably discharged or released from active

duty could receive prenatal and postnatal care (including

delivery) at an Army facility provided that their honorable

discharge papers showed they were pregnant when they left the

service. Before being discharged, pregnant women forwarded a

request through channels to the surgeon general of the service

command in which they would be living; he designated which Army

hospital in their area would provide the necessary care. From 1951

on, women honorably discharged from any armed service on pregnancy

could receive prenatal and postnatal care from any military

medical facility without written approval.8

-

- Until 1949, the

termination of a pregnancy by miscarriage, stillbirth, or

therapeutic abortion did not deter the progress of orders for

discharge on pregnancy. Prevailing opinion assumed that by

becoming pregnant, an unwed woman proved she did not meet the

moral standards necessary for military service and should be

discharged. And since a married woman would probably become

pregnant again, she too should be discharged. In February 1949,

the women's services agreed to modify this rule. Officers and

enlisted women whose pregnancy terminated before the date of their

discharge from the service could request retention on active duty.

The requests went through channels to the Army area commander. The

regulation did not bar unmarried women from requesting retention,

but few wanted to suffer any further embarrassment, and, given the

prevailing attitude toward illegitimate pregnancy, it was almost

certain that such requests would be disapproved. If a living child

were born before the

- [139]

- mother was discharged from

the service, the officer or enlisted woman was discharged under

the pregnancy regulation.9

-

- In 1951, President Truman

issued an executive order (EO-10240) that provided authority to

discharge military women "on parenthood." Although the

order did not require the services to discharge on parenthood,

each service made such a discharge mandatory and issued new

regulations in 1954. If a servicewoman married a man with children

under eighteen years of age in his household for more than 30 days

a year, the new regulations required the woman to request

discharge. Each service permitted women to request retention on

active duty if extenuating circumstances existed. Requests from

unmarried women to adopt or otherwise acquire full-time custody of

a child under eighteen were rarely approved.10

-

- Colonel Galloway's review

of women's discharge policies produced no new recommendations.

Believing that the discharge policies were already as liberal as

possible, she felt unable to change or eliminate any of them to

reduce losses. To abolish discharge on marriage or pregnancy would

make Congress and the public think the Army forced married women

and mothers to remain in service against their will. For its part,

the Army had no desire to keep on duty women who could not work

full time, or be transferred, or receive additional training, or

perform shift or fatigue duties. Colonel Galloway and her staff,

therefore, turned their attention to recruitment and reenlistment

policies in their continuing search for a means of increasing

gains and reducing losses.

-

-

- An examination of WAC

recruitment and reenlistment programs disclosed that Regular Army

enlisted women received no choice of station, unit, or training

course in return for a three-year, or longer, enlistment.

Qualified male enlistees, on the other hand, could chose from an

array of assignment guarantees-overseas duty, a certain command or

division, school training. Pointing to the Corps' obvious need for

more enlistments, Colonel Galloway convinced the G-1 to open the

special school training option to women too. Under it, women high

school graduates who met

- [140]

- the mental and physical

requirements and agreed to enlist for at least three years would

be guaranteed assignment in one of seventeen specialist

courses.11

The option, advertised as the "Reserved Seat

Program" or the "High School Enlistment Option,"

opened in March 1953. Though it did not immediately increase WAC

enlistments, it was a step forward.

-

- A two-year enlistment had

been made available to women in 1952. To young women, eighteen to

twenty years of age (the average enlistment age for WACs), the

shorter alternative was more appealing, especially when a longer

enlistment provided no obvious advantages. Long range, however,

the two-year enlistment was disadvantageous to the Army in two

respects. First, like draftees, few two-year women reenlisted; and

second, after completing four months of training, two-year women

had only twenty months left to spend in the Army versus thirty-two

months for three-year women. For the women who signed up, the

two-year program had several drawbacks as well. They could not

enroll in school training programs longer than eight weeks because

most required students, male or female, to have eighteen to

twenty-four months remaining on their enlistments when they

completed the course. They could not be assigned overseas because

WACs had to serve at least one year on active duty before becoming

eligible for such duty, and all volunteers needed at least one

year remaining on their enlistment when they arrived at a port of

embarkation. Recruiters, however, liked the two-year enlistment

because it sold easily, and it gave them the same amount of credit

as an enlistment for three years. Thus, in FY 1953, which ended

just two months after the Reserved Seat Program went into effect,

of the 2,638 women who enlisted directly from civilian life, 2,354

chose the two-year enlistment.12

-

- To strengthen the

recruitment process, a new mental screening test was introduced in

January 1953-the Armed Forces Women's Selection Test (AFWST). For

women, it replaced the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), in

use since 1950, which men continued to use. Because the AFQT was

designed primarily to test men, it contained a high concentration

of questions on mechanical skills, knowledge of motors and tools,

the sciences, and physics. By contrast, the AFWST emphasized

verbal skills, arithmetic reasoning, and pattern analysis. This

test more aptly measured a woman's potential to be trained in

clerical and administrative positions, typical assignments in the

1950s. The AFWST retained some questions to

- [141]

- evaluate knowledge of

mechanics, science, and other subjects, but such questions were

few. With periodic revisions, the AFWST was used as the primary

mental screening test for WACs and the other women's services

until 1978.13

-

- WAC reenlistment programs

were examined next. In 1952 a reenlistment option had been opened

to all personnel returning from overseas. Under this provision

returning personnel could select the Army post to which they

wished to be assigned. If a vacancy in their MOS and grade existed

at the post, they were able to reenlist for it. If it did not,

they reenlisted without a guaranteed assignment.14

Women who were

due for reenlistment while in the United States had no comparable

choices. Men reenlisting under similar circumstances had a variety

of options-assignment to the Far East, Europe, Alaska, Australia,

or the Caribbean; assignment to a particular branch (Infantry,

Engineers, Signal); or duty (airborne, counterintelligence, a

band); or a specific division (1st Cavalry, 2d, 3d, 7th, 24th, or

25th Infantry).15

In mid-1953, however, Colonel Galloway was able

to obtain some reenlistment options for women. They could reenlist

for duty in a specific geographic Army area or the Military

District of Washington (MDW); at a specific post, if it had a WAC

detachment; or for duty in Europe or the Far East commands,

provided that a proper vacancy existed.16

Beginning in 1955,

servicewomen could reenlist for special school training courses

just as women enlisting directly from civilian life could do.17

-

- On 30 June 1950, the

reenlistment rate for all services had been 59.3 percent; by 30

June 1954, it had fallen to 23.7 percent. These low reenlistment

rates concerned Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson. Before the

Korean War ended, he had appointed a committee to determine why

the rates had dropped so drastically since 1950, and what could be

done to increase them. The committee, headed by Rear Adm. J. P.

Womble, Jr., conducted its study during the summer of 1953 and

sent its report forward in October. It pinpointed the high

civilian employment rate as the basic cause for the lack of

reenlistments and noted that civilian pay was "lucrative,

particularly for the skills taught within the services." The

committee also noted that increases in military pay had not kept

pace with increased costs of living, increases in pay in industry,

or increases in government civilian pay. Contributing factors were

the country's world-

- [142]

- wide commitments, which

meant increased hardships for soldiers because of longer overseas

tours and family separations; a decline in public respect for

military service; and a service-wide dilution in discipline,

morale, and attention to personal problems. To counter these

factors, the Womble Committee advised eliminating incompetent

personnel; estimating the impact of new policies before

implementing them; and improving housing, dependent care,

retirement programs, travel allowances, reenlistment incentives,

and pay.18

-

- These proposals generated

a wave of improvements in the military services. Chief among them

was the passage of legislation that provided a new method of

computing reenlistment bonuses. Up to this time, men and women

received a lump cash sum of $40, $90, $160, $250, or $360 for

reenlistment for two, three, four, five, or six years,

respectively. Now, individuals reenlisting for the first time

would receive an amount determined by multiplying their monthly

base pay by the number of years on their new enlistment contract.

For example, a WAC corporal (E-4) reenlisting for three years

would receive $390-her base pay of $130 times three. Under the old

law she would have received only $90 for reenlisting.19

-

- Using the new legislation,

the Army launched a major reenlistment campaign in 1954.

Reenlistment NCOs were appointed to assist unit commanders in

canvassing, interviewing, and counseling enlisted members on the

advantages of remaining in the service. Each individual qualified

to reenlist was interviewed at least three times before his or her

enlistment ended. The counselor pointed out options for which the

individual qualified, computed the reenlistment bonus money, and

explained the other benefits of military life-retired pay, further

training and educational opportunities, medical and dental care,

etc. Prospective reenlistees were scheduled to see films designed

to encourage them to reenlist-"Ninety-Day Wondering,"

"It's Your Future," or "A Look

-

- With the higher

reenlistment bonus, the Army became more particular about the

qualifications of reenlistees. The Army laid the groundwork for

this selectivity in 1953 by introducing the idea of a "bar to

reenlistment." Unit commanders could document habitual

misconduct or inadequate mental ability and record the information

in an individual's service record. At the end of the individual's

tour, that information would bar the person's reenlistment unless

the problem had been eliminated. A WAC reenlistment guide

admonished commanders "to reenlist as many

- [143]

- good WACs as possible ....

One of the most important parts of your job as Unit Officer is to

promote a high rate of re-enlistment of desirable WACs." 21

-

- Congress passed a number

of other laws that had a good effect on the Army's and the other

services' reenlistment programs. In 1955 and 1958 military pay was

increased and, in 1958, two enlisted grades were added: E-8,

master sergeant or first sergeant, and E-9, sergeant major.

Increased pay made military service more competitive with private

industry; the additional grades increased the prestige of the

enlisted ranks. To provide proficiency incentives, the 1958 pay

bill allowed additional pay for enlisted personnel who

demonstrated excellence in their MOS performance. The first

proficiency level, P-1 pay, gave a man or woman an additional $50

a month; P-2 pay added $100 a month; and P-3 pay added $150 a

month. As an additional benefit, the 1958 bill also offered one

year of college for every three-year enlistment or reenlistment

and two years of college for every six-year enlistment or

reenlistment. And, at the beginning of this period of goodwill and

good public relations, the Defense Department, at the urging of

Director Galloway and several veterans groups, had sponsored a

bill, passed by Congress on 24 August 1954, giving VA benefits to

WAACs who had been honorably discharged on physical disability

between 14 May 1942 and 30 September 1943.22

-

- Between 1953 and 1955, by

providing options for women in duty stations and schools, Colonel

Galloway succeeded in bringing the women's reenlistment program

almost in line with the men's. The WAC reenlistment rate, which

had fallen to 18.7 percent in 1954, had swung upward to 35.6

percent by June 1955.23

Greater freedom of choice, increased

enlistment bonuses, and higher pay all contributed to the improved

reenlistment rate. Another major event during 1954 also had a

favorable impact on WAC recruiting and reenlistment-the opening of

a new WAC center and WAC school at Fort McClellan, Alabama.

-

-

- Discussion about a new WAC

center and WAC school had begun after a November 1950 visit to

Camp Lee by Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, Deputy Chief of Staff of

the Army for Administration. On his return to the Pentagon, he

asked the G-1, then General Brooks, to find a better training area

for the WACs. General Ridgway observed: "The

- [144]

- barracks these young

American women occupy . . . can never create any pride of

occupancy. They are the dirty old temporary type of wooden shack.

I think we can do better." 24

General Brooks agreed and

forwarded the memorandum to Colonel Hallaren, then the director of

the WAC, and received a surprising reply. Colonel Hallaren

recommended that the WAC training center concept be eliminated and

that men and women be trained together in the Army's basic

training system. She pointed out that few differences existed in

their training programs except for the weapons and tactical

training given men. She proposed for a pilot model that "a

training battalion be activated at a permanent post such as Fort

Benning to provide joint training for men and women in common

subjects. If successful, similar battalions might be activated at

other training divisions until the entire function of a WAC

training center had been absorbed."25

Men and women would be

assigned to separate companies but would share classrooms,

instructors, training aids, and equipment. Such a program, she

felt, would reduce training and travel costs, "create a

highly desirable orientation for both men and women entering the

Army," and, hopefully, improve soldiers' attitudes toward

women in the Army.26

-

- When her proposal received

no support, Colonel Hallaren dropped the idea and turned to the

selection of a post suitable for a WAC training center. A site

selection committee, appointed by the chief of staff, was already

at work. The members of the committee, who represented the G-1,

the G-3, the G-4, the director of the WAC, and the chief of Army

Field Forces, reviewed the availability of land and facilities at

the sites considered only a few years earlier when Camp Lee had

been chosen: Fort Bragg, Fort Benning, Fort Riley, and Fort

McClellan. Their choice was Fort McClellan. The Alabama location

had a mild climate, allowing a maximum number of outdoor training

days; adequate transportation, both ground and air; and proximity

to the service schools where the WACs would receive specialist

training. In December 1950, the chief of staff approved Fort

McClellan as the site of the WAC Center and WAC School .27

-

- Located five miles north

of Anniston, Alabama, in a valley west of the Choccolocco

Mountains, Fort McClellan was first opened in 1917. Named in honor

of the Civil War general-in-chief of the Union armies, George B.

McClellan, the post had been an infantry training center during

both world wars and had been closed, reverting to custodial

status, after those wars had ended. During World War II, Fort

McClellan's large hospital (1,728 beds) and station complement had

included two WAC detachments-one white, one black-whose members

worked in

- [145]

- the hospital, post

headquarters, motor pool, bakery, service club, supply offices,

and warehouses.28

-

- On 4 January 1951, the

Department of the Army announced that Fort McClellan, closed in

1947, would reopen as a permanent post and that the Chemical

School and Replacement Training Center would move there from

Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland. Chemical training activities would

occupy the existing buildings on post. Meanwhile, a task force

prepared detailed descriptions and justifications for moving the

WAC Center to Fort McClellan and constructing facilities there for

both the WAC and the Chemical Corps. The plan was presented to

Congress and approved by the lawmakers. On 21 September 1951,

President Truman signed the appropriations bill that authorized

$23,333,250 for the projects at Fort McClellan.29

-

- Bids on construction

opened in June 1952. In September a contract was signed with Bruce

Construction Company of Miami, Florida. The WAC deputy director,

Lt. Col. Emily C. Gorman, reported: "When the bids were let

and the actual working construction got underway, the cost of the

WAC Center . . . was established at $7,300,000." 30

Initial

construction costs, however, totaled $10.5 million, even though in

the legislative process, approximately $3 million had been deleted

from the WAC project and some needed buildings were lost.31

-

- A formal ground-breaking

ceremony took place on 7 October 1952, with Maj. Patricia E. Grant

representing the director of the WAC, who could not be present.

During the construction phase, Major Grant had been the only WAC

officer at the post. She represented the director in monitoring

the progress of the construction and assisted the post commander

and his staff in their planning. She contacted the merchants and

civic leaders in the Anniston area and gave talks on WAC history

and training courses to business, church, and school groups

throughout the state. She established the goodwill that future

WACs would enjoy within the community. The WAC staff advisers at

Headquarters, Third Army, in this period-Lt. Cols. Rebecca Parks

and Verna A. McCluskey, and Maj. N. Margaret Young-visited

frequently and provided what assistance they could.

-

- Strikes, bad weather, and

shortages of building supplies caused by the Korean War slowed

construction. The contractor, after changing the

- [146]

-

MAJ. GEN. CHARLES

D. PALMER, G-3, ARMY FIELD FORCES, FORT MONROE, confers with officers

from WAC Center and WAC School regarding the move from Fort Lee to Fort

McClellan. Left to right: Maj. Martha D. Allen, S-3, WAC Center, Maj.

Sue Lynch, Assistant Commandant, WAC School, Lt. Col. Eleanore C. Sullivan,

Commander, WAC Center, and Commandant, WAC School, March 1953.

-

- "moving in" day

three times, finally set 25 June 1954 as the date, and the WAC

Center commander, Lt. Col. Eleanore C. Sullivan, immediately set

in motion the detailed moving plan that her immediate staff had

prepared. 32

-

- Beginning on 10 May 1954,

advance parties of WACs began arriving at Fort McClellan, which,

effective 10 June, would become the home of

- [147]

- the WAC Center and WAC

School. The largest group led by Lt. Col. Lucile G. Odbert, deputy

WAC Center commander, arrived on 12 June. The enlisted members of

the group cleaned buildings, arranged furniture and equipment, and

received property as it arrived from Fort Lee. The first shipment

of property, supplies, and equipment left Fort Lee on 1 June. By

16 August, over 120 tons of station and personal property had

arrived at Fort McClellan. To reduce transportation costs, no new

basic trainees were sent to Fort Lee after 17 June, and of those

already there as many trainees and students as possible were

graduated. From 1 July to 9 August, the WAC officially operated

two training centers so that no training time would be lost. Some

trainee transfers, however, were necessary, and two platoons of

Company A, WAC Training Battalion, who had begun their training at

Fort Lee in early June, completed it at Fort McClellan in August.33

-

- WAC recruiters outdid

themselves in obtaining new enlistees and officers to enter the

courses at the new center and school that summer. Two hundred

women began their basic training on 5 July. The WAC Clerical

Procedures and Typing Course, restored to WAC School after being

disbanded in 1950 to make room for more recruits at Fort Lee,

commenced its first class on 16 August with forty students. Class

VI of the WAC Officer Basic Course and Class X of the WAC Officer

Candidate Course, the first combined class, began on 26 August

with twenty-two student officers and six officer candidates.34

-

- The WAC area was divided

into two major sections-the WAC School and the WAC Center, which

included the WAC Training Battalion. The Center's main building

contained offices for the battalion commander, her staff and

instructors, twenty-five classrooms, and a small gymnasium. Across

the street were six cream colored barracks buildings, made of

steel-reinforced concrete blocks, with asphalt tile floors and

pastel-painted interiors. Basic trainees occupied five of the

barracks, and members of the 14th Army Band (WAC) lived in the

sixth, part of which was converted into rehearsal rooms. Also in

the battalion complex were a mess hall, which could seat 400 at a

time, and a building for fitting and issuing WAC uniforms.35

- [148]

-

NEWLY ENLISTED

WOMEN arrive at the train station, Anniston, Alabama, to begin basic

training at the new WAC Center, Fort McClellan, July 1954.

-

- Each barracks had three

stories and a basement. On the first floor were offices for the

company commander and her staff, a kitchen, reception area,

dayroom, and bathroom with private toilets, individual showers,

and two bathtubs. The basic trainees lived on the second and third

floors in large bays without partitions, two bays per floor. Each

bay contained forty-five to fifty cots, footlockers, wall lockers,

and steel clothes closets. In addition, each floor had a laundry

room with automatic washers, dryers, and ironing boards; a large

bathroom; and several cadre rooms in which the unit's platoon

sergeants lived. The basements contained offices for the unit

supply officer and her assistants, storage rooms for the unit's

supplies and for the basic trainees' suitcases, and a mailroom.

-

- The WAC School was about a

half-mile from the basic training area. The main building

contained offices for the assistant commandant, her staff, and the

instructors as well as twenty-five classrooms, a bookstore, and a

library. Student officers and officer candidates lived in a

barracks designed like those at the Center for basic trainees,

except that partitions

- [149]

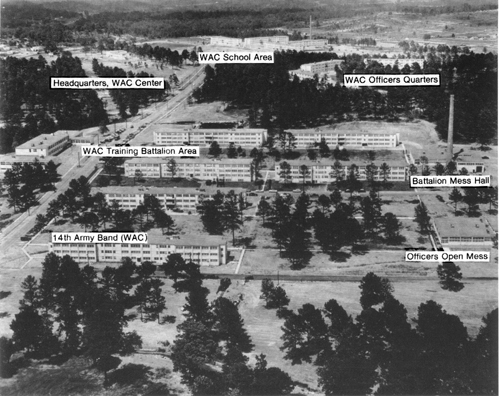

- WAC AREA, FORT McCLELLAN,

1954

-

- were provided between each

two cots in the bays. Enlisted students lived in another barracks

in open bays without partitions. Headquarters and Headquarters

Company, also located in this area, held the permanent party

enlisted women who were assigned to WAC Center headquarters, WAC

School, Fort McClellan's post headquarters, the hospital, or

another activity on post. Another large mess hall was located in

this area to serve the women who lived in these barracks.

-

- WAC officers assigned to

activities on post lived in bachelor officer quarters in the WAC

area. Lieutenants and captains shared a suite, which consisted of

two bedrooms separated by a bathroom. Majors and above had

individual suites-living room, bedroom, and bath. The few small

cottages available were assigned to the officers who occupied key

positions, e.g., the WAC Center commander/School commandant,

assistant commandant, battalion commander.

-

- WAC Center headquarters,

which stood on a hill in the center of the area and overlooked the

parade ground, held offices for the commander and her immediate

staff, a small auditorium, message center, and printing shop.

- [150]

- Colonel Sullivan, Center

commander, arrived on 15 July to assume command of the new WAC

facility from her deputy, Colonel Odbert. A few days later, the

citizens of Anniston welcomed their new neighbors by proclaiming

21 July as "WAC Day." The main streets of the city

(population 26,000) were draped with bunting and welcome banners;

merchants placed placards of welcome in their store windows; and

the local newspaper and radio station featured WAC activities

throughout the day. WAC Day initiated an enduring and warm

relationship between the members of the WAC at Fort McClellan and

the citizens of Anniston and the adjoining towns of Oxford,

Jacksonville, Weaver, and Heflin.

-

- Dedication of the WAC

Center and WAC School was deferred until 27 September 1954, when

all activities were fully operational. General Ridgway, now Army

chief of staff, was the principal speaker at the ceremony. He told

the 700 or so military and civilian guests: "Here the

traditions of the Women's Army Corps will be passed on to those

yet to wear the proud insignia of the WAC. They will become

familiar with the splendid achievements of their predecessors and

with the great honor and responsibility that is theirs in wearing

the uniform of their country's Army forces."36

He concluded

the ceremony by unveiling a large bronze dedicatory plaque that

read: "The WAC Center, dedicated to members of the Women's

Army Corps who served their country in peace and war. Fort

McClellan, Alabama, 27 September 1954." The plaque was later

mounted on a marble slab and permanently placed in an area called

the WAC Memorial Triangle across the street from the WAC chapel.37

-

- Support in the field as

well as in Washington had helped make the new WAC "home"

possible. Lt. Gen. Alexander R. Boning, Commanding General, Third

U.S. Army, at Fort McPherson, Georgia, the area commander, took an

active interest in the construction and operation of the Center,

ensuring the resources necessary for its success. Providing

day-today assistance were the Fort McClellan post commanders-Col.

Michael Halloran, who retired in August 1954, and his replacement,

Col. William T. Moore, who served until 1958.

-

- Attainment of the branch

"home" made a difference in the progress of most WAC

programs. It provided visible proof that Congress and the Army

appreciated the Women's Army Corps and wanted it to prosper. The

new Center and School thus enhanced the prestige of the WAC within

the Army, improved the morale of women on duty, and gave WAC

recruiters a significant new selling point for obtaining recruits

and student officers. During the year that ended 30 June 1954,

2,958 enlisted women entered the Corps; in the year that followed,

4,384. And while only 90 women received commissions in FY 1954,

and only 53 in FY 1955, 115 were appointed in FY 1956.38

- [151]

-

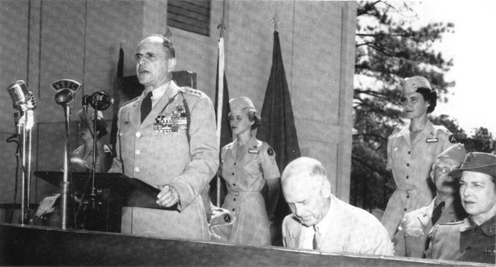

GENERAL MATTHEW

B. RIDGWAY, ARMY CHIEF OF STAFF, speaking at the dedication of the

new WAC Center and WAC School at Fort McClellan, 27 September 1954. To

General Ridgway's left are Senator Lister Hill of Alabama, Brig. Gen.

Charles G. Hone, Corps of Engineers, and Col. Irene O. Galloway, Director,

WAC. In the background are Pfc. Flora G. Thompson and 1st Lt. Edna Lee

Gray, escorts.

-

-

- In her continuing search

for ways to increase WAC personnel strength, Colonel Galloway also

worked to improve job satisfaction. A survey conducted in August

1945 had reported, "Satisfaction with her job is probably the

single most important factor in an enlisted woman's evaluation of

her role as a member of the Women's Army Corps and, consequently,

her general morale and adjustment in Army life."39

Thus, if

ways could be found to increase job satisfaction, the reenlistment

rate should also rise.

-

- Job satisfaction to most

WACs meant doing work that was meaningful and that occupied them

fully during duty hours. During World War II, after the WAAC had

overcome the Army's initial resistance to the idea that women

could be more than clerks, cooks, telephone operators, and

drivers, opportunities opened in hundreds of military occupational

specialties (MOSs). This large bank of jobs contributed most to

the successful employment of women during the war. Although the

majority of women worked in administration, communications, and

medical care and treatment, they knew that some of their peers

worked in a variety of

- [152]

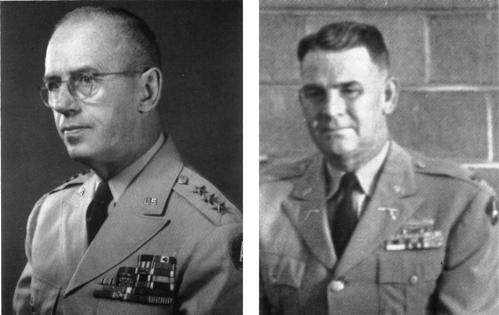

| LT. GEN. ALEXANDER R.

BOLLING, Commanding General, Third U.S. Army, 1953. |

|

COL. WILLIAM T.

MOORE, Commander, Fort McClellan (1954-1958). |

-

- unusual occupations. They,

thus, sensed that the Army offered women increased opportunities.

Knowing they had a choice in work assignment, location, and even

the uniform they wore was important to the women and contributed

to their job satisfaction.

-

- After World War II, the

G-1 ordered a major study aimed at developing a modern personnel

management system and MOS structure for enlisted personnel. The

new system, introduced during the first year of the Korean War,

encompassed 490 MOSS arranged in 31 major career fields and 194

areas of specialization. Each new MOS description included a

detailed outline of work performed, its physical and mental

requirements, its training requirements, and a statement about

whether or not a WAC could be assigned to it. From this, the G-1

developed the first authorized list of MOSS in which WACs could be

trained and had it issued as a special regulation. Although

revised periodically in the years to follow, the list was the

controlling factor in determining WAC assignments.40

- [153]

- During the development of

the new system, other studies were also conducted. In 1949,

Surgeon General Raymond W. Bliss authorized a test to determine

"to what extent women could be substituted for men in the

operation of Army hospitals."41

The experiment began on 1

June 1949 at Murphy General Hospital, a 500-bed facility near

Boston, Massachusetts. Military and civilian women gradually

replaced males in the majority of medical and administrative jobs

in the hospital and in the facility support jobs required when the

hospital functioned as a military post. Civilian and Army nurses

and members of the Women's Medical Specialist Corps filled

positions in the hospital's clinics, wards, and offices. WAC

officers, warrant officers, and enlisted women received either

school training or on-the-job training so that they could fill

administrative and technical positions. By the end of the year, 16

WAC officers, 2 WAC warrant officers, and 240 enlisted women had

been assigned to the hospital.

-

- Women, however, did not

fill all positions. No women Army doctors were available to

participate because the law permitting them to be commissioned in

the Army of the United States (AUS) had expired in 1948. And costs

precluded the hospital's hiring of civilian women doctors for the

experiment. In another case, enlisted women did not replace the

janitorial staff, mostly male civilians, because no comparable

MOSS existed for such jobs. The test administrator also excluded

WACs from positions that were located in isolated areas, that

called for physical strength beyond a woman's capacity, that would

require women to discipline men, and that would offend the

"modesty of the average woman and sense of delicacy of male

patients" and "would make the service of a male

attendant desirable."42

-

- On 30 April 1950, Murphy

General Hospital was deactivated and the study was discontinued.

Col. John M. Welch, commander of the hospital, reported that

during the experiment, the hospital had operated with full

effectiveness. He recommended that the maximum percentage of women

in hospital activities be 92; in hospital-post activities, 60. In

hospital functions, however, he recommended that men be assigned

for such tasks as heavy lifting in connection with male-patient

care and treatment. WAC officers had performed well as hospital

executive officer, management officer, personnel officer, medical

supply officer, mortuary officer, and transportation officer. A

WAC warrant officer had served competently as hospital registrar,

and a WAC master sergeant had served successfully as sergeant

major of the hospital. The jobs to which women were not assigned

were those usually associated with great physical strength: fire

fighter, prison guard, psychiatric attendant, boiler fireman, and

butcher. The study supported the conclusions of other studies

being conducted

- [154]

- during the period, but it

did not result in any changes in utilization of women in the

medical career field .43

-

- A different study began in

October 1949 at Walter Reed General Hospital (Forest Glen

Section), Washington, D.C. Twenty-nine enlisted women entered an

experimental 48-week course in practical nursing-the Advanced

Medical Technicians Procedures Course. The course curriculum,

developed by Maj. Isabelle A. G. Mason, ANC, was taught by her,

five other Army nurses, and one dietitian. Based on objective

periodic reviews, tests, and evaluations, the course was

considered a success. Twenty-one WACs graduated from the first

class. The surgeon general and the chief of Army Field Forces

approved continuance of the course, and enlisted men were admitted

to subsequent classes.44

-

- For the next three years,

the practical nursing course was conducted solely at Walter Reed

Army Medical Center. The Korean War increased the demand for its

graduates, and beginning in 1952, similar courses opened at

Letterman and Fitzsimmons General Hospitals in San Francisco and

Denver, respectively. Graduates took practical nurse licensing

examinations in the states in which they were assigned. The

commanding general at Walter Reed Army Medical Center commented:

"Many practical nurses are serving overseas where they assist

Army nurses in giving the highest quality of nursing care. In

augmenting the nursing service, these technicians have become a

most welcome asset in the medical field."45

-

- Despite the results in the

medical area, the enlisted personnel management system initiated

in November 1950 was not a complete success. Commanders complained

that the MOS and classification structure with its 31 career

fields and 194 specializations was too complicated to administer.

The exigencies of the Korean War also made it difficult to

implement some of the innovative provisions of the new system,

such as efficiency reports, competitive promotions, pooling of

grade vacancies, and MOS testing. These provisions were suspended

until the war ended. In December 1951, Army Chief of Staff J.

Lawton Collins directed the chief of Army Field Forces to devise a

new MOS structure, career fields, and classification program. Work

on the project-with the major commanders, the chiefs of the

administrative and technical services, and the Army staff at the

Pentagon participating-began early in 1952.46

- [155]

- The WAC did not have a

role in the new study, and no WAC officer was included in the

study group. Upon reviewing the new MOS structure when it was

proposed in 1953, Colonel Galloway compared each MOS declared

suitable for WACs against the women's utilization policies then in

effect. She told the chief of the study group that seventy MOSS on

the "suitable" list did not meet the criteria laid down

in the policies and recommended the list be made compatible with

WAC standards. She noted, for example, that eighteen MOSs in the

artillery series were not appropriate for the training and

assignment of WACs. Although Colonel Galloway wanted the widest

possible spectrum of MOSs, she also wanted the selection and

assignment of women to be guided by what she considered sound

policies. Assignments that would require combat training and

possibly combat duty for women were unacceptable.

-

- A new MOS structure

introduced by the Army in 1955 made a number of changes in

enlisted personnel management. Ten occupational areas replaced the

thirty-one career fields. Under the new MOS code, a WAC

administrative specialist who formerly held MOS 1502 now held MOS

717.60. The first two digits (71) showed her occupational area

(Administration-71); the third digit her specialty (Personnel-7).

The suffix digits (.60) indicated her skill level and special

qualifications, if she had any. The new system also provided

separate grades and titles for NCOs and specialists. Under this

restructuring, 128 of the 385 Army MOSs were opened to enlisted

women. The criteria for WAC utilization were now included in the

same regulation that outlined policies for men (AR 611203,

Enlisted Personnel Selection and Classification, 2 March 1955).

This was a small step forward. Those facets of the new system

whose implementation had been suspended during the Korean

War-enlisted efficiency reports, MOS testing to determine

proficiency, and an Army-wide promotion system based on merit-were

put into effect between 1955 and 1960. These changes brought

marked improvement in the management of enlisted personnel, but

neither opened new fields nor closed old ones to the WACs.

-

- Colonel Galloway's tenure

as director was a time of sound WAC accomplishment: enlistment

gains had finally exceeded losses; three-year enlistments had

surpassed two-year enlistments; and the reenlistment rate was

higher than in 1953. These improvements were, in part, a result of

increased military pay and reenlistment bonuses, the Army's new

management system for enlisted personnel, and the WAC's move to a

new home at Fort McClellan. They were also the result of Colonel

Galloway's success in adding enlistment options and improving job

satisfaction for the WACs-achievements that earned her the respect

and affection of the women of the Corps.

- [156]