- Chapter I:

-

- Operation Iceberg

-

- On 3 October 1944 American forces

in the Pacific Ocean Areas received a directive to seize positions in the

Ryukyu Islands (Nansei Shoto). Okinawa is the most important island of the

Ryukyu Group, the threshold of the four main islands of Japan. The decision

to invade the Ryukyus signalized the readiness of the United States to penetrate

the inner ring of Japanese defenses. For the enemy, failure on Okinawa meant

that he must prepare to resist an early invasion of the homeland or surrender.

-

-

- Operation ICEBERG, as the plan for

the Okinawa campaign was officially called, marked the entrance of the United

States upon an advanced stage in the long execution of its strategy in the

Pacific. Some 4,000 miles of ocean, and more than three years of war, separated

Okinawa from Pearl Harbor. In 1942 and 1943 the Americans had contained the

enemy and thrown him back; in 1944 their attack gathered momentum, and a series

of fierce island campaigns carried them toward the Japanese inner stronghold

in great strides.

-

- The Allied advance followed two main

axes, one through the islands of the Central Pacific, the other through the

South and Southwest Pacific. Navy task forces and some other elements operated

on both fronts as needed. The result was "unremitting pressure"

against Japanese military and naval might, a major objective of American strategy.

-

- Near the close of 1943, a thrust at

the Gilbert Islands from the Central Pacific, in which Tarawa, Makin, and

Apamama were seized, paved the way for the assault on the Marshalls on 31

January 1944. American forces captured Kwajalein, Majuro, and Eniwetok, and

their fleet and air arms moved forward. At the same time, American carriers

heavily attacked Truk, and that formidable enemy naval base in the Carolines

was thenceforth immobilized. Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in the Marianas fell

to American arms in the summer of 1944, and, in the First Battle of the Philippine

Sea, the U. S. Navy administered a crushing

- [1]

- defeat to the Japanese fleet that

tried to interfere with the American push westward. In September and October

the Americans occupied Ulithi in the western Carolines for use as an anchorage

and advanced fleet base, and took Angaur and Peleliu in the Palau Islands,

situated close to the Philippines.

-

- Meanwhile, American forces in the

South and Southwest Pacific were approaching Mindanao, southernmost of the

Philippine Islands, by advances through the Solomons and New Guinea in which

Japanese armies were neutralized and isolated on Bougainville, New Ireland,

and New Britain. The capture of Wakde on the northeastern coast of New Guinea

in May 1944 was followed by the seizure of Biak and Noemfoor. During the summer

a Japanese army attempting to break out from Wewak in Australian New Guinea

was subdued. The invasion of Morotai in September placed American forces within

300 miles of Mindanao.1

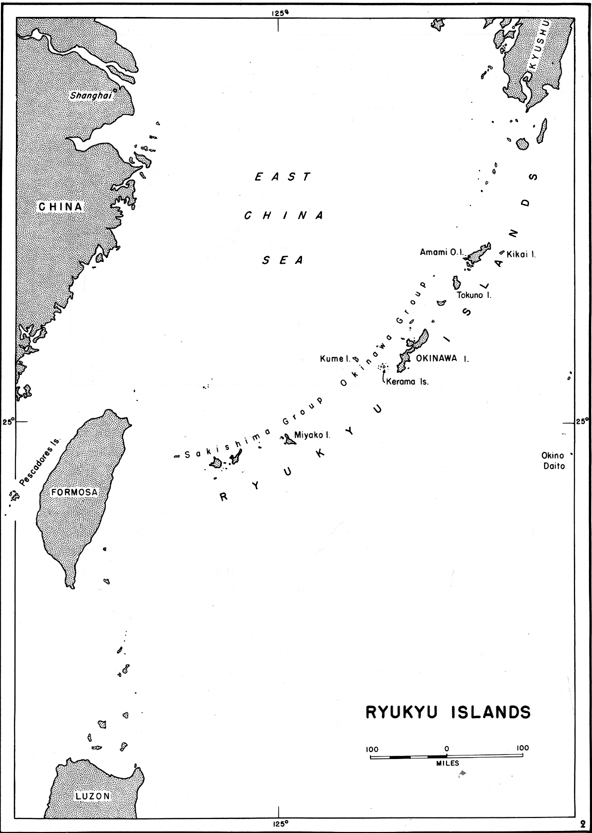

(See Map No. I.)

-

- The ultimate goal of American operations

in the Pacific was the industrial heart of Japan, along the southern shores

of Honshu between the Tokyo plain and Shimonoseki. American strategy aimed

to reach this objective by successive steps and to take advantage, on the

way, of Japan's extreme vulnerability to submarine blockade and air bombardment.

Throughout most of 1944 Army and Navy staffs in the Pacific Ocean Areas had

been planning for the invasion of Formosa (Operation CAUSEWAY) in the spring

of 1945. On the basis of the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive of March 1944,

the general concept of this operation had been outlined, the availability

of troops considered and reviewed many times, and the assignment of task force

commanders announced. On 23 August, a joint staff study for CAUSEWAY had been

published. It was clear that Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief,

U. S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, intended to invade Formosa after

Southwest Pacific forces had established positions in the Central and Southern

Philippines; CAUSEWAY, in turn, was to be followed by operations against the

Ryukyus and Bonins, or against the China coast. Either course would lead eventually

to assault on the Japanese home islands.2

-

- On 15 September the Joint Chiefs directed

Gen. Douglas MacArthur to seize Leyte on 20 October, instead of 20 December

as planned, and to bypass

- [2]

- Mindanao. At the same time, Admiral

Nimitz was instructed to bypass Yap 3

On the next day Admiral Nimitz reconsidered the Formosa operation. He believed

that the early advance into the Central Philippines, with the opportunity

of acquiring the desired fleet anchorages there, opened up the possibility

of a direct advance northward through the Ryukyus and Bonins rather than through

Formosa and the China coast. He reviewed the objectives of CAUSEWAY the establishment

of air bases from which to bomb Japan, support China, and cut off the home

islands from resources to the south- with reference to the new possibility

and in a letter to his Army commanders requested their opinions on the subject.4

-

- Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, Jr.,

Commanding General, U. S. Army Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas, replied that only

those steps should be taken which would lead to the early accomplishment of

the ultimate objective-the invasion of Japan proper. From this point of view

the occupation of Formosa as a stepping stone to an advance on Japan via the

China coast did not, in his opinion, offer advantages commensurate with the

time and enormous effort involved. He proposed instead, as a more economical

course, a dual advance along the LuzonRyukyus and the Marianas-Bonins axes.

He fully agreed with General MacArthur's plan to seize Luzon after Leyte.

The seizure of Luzon would provide air and naval bases in the Philippines

from which enemy shipping lanes in the China Sea could be blocked and, at

the same time, Formosa effectively neutralized. From the ample bases in Luzon,

it would be possible and desirable to seize positions in the Ryukyus for the

prosecution of air operations against Kyushu and Honshu. The occupation of

bases in the Bonins would open another route from the Marianas for bomber

operations against Japan. The air assaults on Japan would culminate in landings

on the enemy's home islands 5

-

- Lt. Gen. Millard F. Harmon, Commanding

General, U. S. Army Air Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas, in his reply to Admiral

Nimitz referred to a previous letter which he had written to the Admiral,

recommending, as an alternative to the invasion of Formosa and the China coast,

the seizure of islands in the Ryukyu chain, for development as air bases from

which to bomb Japan. He restated these views and emphasized his opinion that

if the objective of CAUSEWAY was the

- [3]

- acquisition of air bases it could

be achieved with the least cost in men and materiel by the capture of positions

in the Ryukyus.6

-

- The commander of the ground troops

designated for CAUSEWAY, Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, Jr., Commanding General,

Tenth Army, presented the primary objection to the entire Formosa operation.

He informed Admiral Nimitz that the shortages of supporting and service troops

in the Pacific Ocean Areas made CAUSEWAY unfeasible. General Buckner added,

about a week later, that if an invasion of Luzon was planned the need for

occupying Formosa was greatly diminished. 7

-

- Admiral Nimitz communicated the substance

of these views to Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet.

The latter, who had been the chief proponent of an invasion of Formosa, proposed

to the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 20ctober 1944 that, in view of the lack of

sufficient resources in the Pacific Ocean Areas for the execution of CAUSEWAY

and the War Department's inability to make additional resources available

before the end of the war in Europe, operations against Luzon, Iwo Jima, and

the Ryukyus be undertaken successively, prior to the seizure of Formosa. Favorable

developments in the Pacific and in Europe might make CAUSEWAY feasible at

a later date.8

On the next day, 3 October, the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive to

Admiral Nimitz to seize one or more positions in the Ryukyu Islands by 1 March

1945.9

On 5 October Admiral Nimitz informed his command that the Formosa operation

was now deferred and that, after General MacArthur invaded Luzon on 20 December

1944, the Pacific Ocean Areas forces would seize Iwo Jima on 20 January 1945

and positions in the Ryukyus on 1 March. 10

-

- The projected Ryukyus campaign was

bound up strategically with the operations against Luzon and Iwo Jima; they

were all calculated to maintain unremitting pressure against Japan and to

effect the attrition of its military forces. The Luzon operation in December

would allow the Southwest Pacific forces to continue on the offensive after

taking Leyte. The occupation of Iwo Jima in January would follow through with

another blow and provide a base

- [4]

- MAP NO. 1

-

- [5]

- MAP NO. 2

-

- for fighter support for the B-29's

operating against Japan from the Marianas. The seizure of Okinawa in March

would carry the war to the threshold of Japan, cut the enemy's air communications

through the Ryukyus, and flank his sea communications to the south. Okinawa

was, moreover, in the line of advance both to the China coast and to the Japanese

home islands.11

-

- The direct advance to the Ryukyus-Bonins

line from the Luzon-Marianas was thus conceived within the framework of the

general strategy of destroying by blockade and bombardment the Japanese military

forces or their will to resist. The Ryukyus were within medium bomber range

of Japan, and it was estimated that 780 bombers, together with the necessary

number of fighters, could be based there. An advanced fleet anchorage was

available in Okinawa. From these airfields and naval bases American air and

naval forces could attack the main islands of Japan and, by intensified sea

and air blockade, sever them from the Japanese conquests to the south. The

captured bases could also be used to support further operations in the regions

bordering on the East China Sea. Finally,

- [6]

- the conquest of the Ryukyus would

provide adequate supporting positions for the invasion of Kyushu and, subsequently,

Honshu, the industrial heart of Japan. 12

-

-

- The Islands

- The Ryukyu Islands lie southwest of

Japan proper, northeast of Formosa and the Philippines, and west of the Bonins.

(See Map No. l.) The islands, peaks of submerged mountains, stretch in an

arc about 790 miles long between Kyushu and Formosa and form a boundary between

the East China Sea and the Pacific Ocean. The archipelago consists of about

zoo islands, only 30 of which are large enough to support substantial populations.

The climate is subtropical, the temperature ranging from about 60° F. to 83°

F. Rainfall is heavy, and the high humidity makes the summer heat oppressive.

The prevailing winds are monsoonal in character, and between May and November

each year the islands are visited by destructive typhoons.13

-

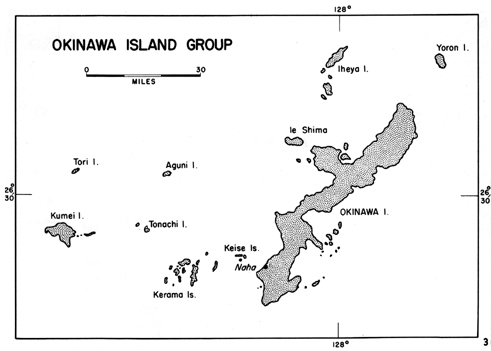

- Approximately in the center of the

arc is the Okinawa Group (Gunto) of some fifty islands clustered around the

island of Okinawa. The Kerama Islands lie in an area from ten to twenty miles

west of southern Okinawa. Kume, Tonachi, Aguni, and Tori form a rectangle

to the north of the Kerama Group. Ie Shima stands off the jutting tip of the

Motobu Peninsula on northern Okinawa, while farther to the north lie the Iheya

Islands and Yoron. A chain of small islands, called by the Americans the Eastern

Islands, extends along the eastern shore of southern Okinawa. Lying in the

path of the Japan Current, the entire Okinawa Group is surrounded by seas

warm enough to allow the growth of coral, and hence all the islands are surrounded

by fairly extensive reefs, some of which extend several miles off shore. (See

Map No. 2.)

-

- Okinawa is the largest of the islands

in the Ryukyus. Running generally north and south, it is 60 miles long and

from a to 18 miles wide, with an area of

- [7]

- burial tombs characteristics of the Okinawan landscape stand out

clearly in this aerial view

- (above) just north of Shuri.

-

- OKINAWANS, their head man, and a native priest (white hat) gather

around an American

- soldier-interpreter as he ask questions

-

- [8]

- 485 square miles. It is entirely fringed

with reefs: on the western side the reef lies fairly close to shore and is

seldom over a mile wide; on the eastern side, where the coast is more sheltered,

the reef extends for some distance off shore, the widest and shallowest points

being north of Nakagusuku Bay. (See Maps Nos.II and III.)

-

- When Commodore Perry's ships sailed

into Naha Harbor, on 26 May 1853, Okinawa was a semi independent country,

paying tribute to China and Satsuma. It was annexed in 1879 by Japan, which

integrated the Okinawan people almost completely into the Japanese governmental,

economic, and cultural structure. The racial origins of the Okinawans are

similar to, but not identical with, those of the Japanese, and the Okinawan

stock and culture had been subject to extensive Chinese influence. While the

Okinawans generally resemble the Japanese in physique, they differ appreciably

in their language, the native Luchuan tongue. The predominant religion among

the Okinawans is an indigenous, animistic cult, of which worship of fire and

the hearth is typical; veneration of ancestors is an important element in

this religion and the burial tomb the most characteristic feature of the Okinawa

landscape a feature which the Japanese were to convert into a formidable defensive

position.

-

- The standard of living of the Okinawan

people is low; the Japanese made no attempt to raise it, regarding the Okinawans

as inferior rustics. Most of the inhabitants subsist on small-scale agriculture.

When the invading Americans climbed up from the beaches, they found every

foot of usable land cut into small fields and planted with sugar cane, sweet

potatoes, rice, and soy beans. In 1940 the population of the island was 435,000.

-

- The terrain in northern Okinawa, the

two-thirds of the island above the Ishikawa Isthmus, is extremely rugged and

mountainous. A central ridge, with elevations of 1,000 feet or more, runs

through the length of the region; the ridge is bordered on the east and west

by terraces which are dissected by ravines and watercourses, and it ends at

the coast in steep cliffs. About 80 percent of the area is covered by pine

forests interspersed with dense undergrowth. Troop movements are difficult

in the region as the use of vehicles is confined to the poor road that hugs

the western shore. The Motobu Peninsula, which is nearly square in shape and

juts to the west, has also a mountainous and difficult terrain. Two mountain

tracts separated by a central valley run east and west the length of the peninsula.

Successive coastal terraces are well developed on the north, east, and west

of the peninsula. About three and one-half miles off the northwest end of

the Motobu Peninsula is the small flat-topped island of Ie Shima, with a sharp

pinnacle about 500 feet high at the eastern end.

- [9]

- The southern third of Okinawa, south

of Ishikawa, is rolling, hilly country, lower than the north but broken by

terraces, steep natural escarpments, and ravines. This section is almost entirely

under cultivation and contains threefourths of the population of the island;

here, too, are the airfields and the large towns-Naha, Shuri, Itoman, and

Yonabaru. It was in this area that the battle for Okinawa was mainly fought.

The limestone plateau and ridges are ideal for defense and abound in natural

caves and burial tombs, easily developed into strong underground positions.

Generally aligned east and west, the hills offer no north-south ridge line

for troop movement, and thus they provide successive natural lines of defense,

with frequent steep slopes created by artificial terracing. Rice paddies fill

the lowlands near the coasts. The roads are more numerous than in the north,

but, with the exception of those in Naha and its vicinity, they are mostly

country lanes unsuited for motorized traffic. Drainage is generally poor,

and heavy rains turn the area into a quagmire of deep, clay-like mud.

-

- South of Zampa Point on the west there

is a 15,000-yard stretch of coast line which includes nearly 9,000 yards of

beaches, divided by the Bishi River. These are known as the Hagushi beaches,

deriving their name from a small village at the mouth of the river. The beaches

are not continuous but are separated by cliffs and outcropping headlands.

They range from 100 to 900 yards in length and from 20 to 45 yards in width

at low tide, and some are completely awash at high water. A shallow reef with

scattered coral heads borders the entire stretch of beach and, in many places,

is almost a barrier reef, with deeper water between its crest and the shore

line than immediately to seaward. The beaches are for the most part coral

sand and most have at least one road exit. A low coastal plain flanks the

beaches from Zampa Point south to Sunabe; it is dominated by rolling hills

which afford excellent observation, good fields of fire along the beaches,

and extensive cover and concealment. Less than 2,000 yards inland on the plain

lie the Yontan and Kadena airfields, north and south of the Bishi River. A

400foot-high hill mass, rising southeast of Sunabe and extending across the

center of the island, dominates the entire beachhead area. Composed of innumerable

sharp ridges and deep ravines, it is a major obstacle to rapid troop movements

and can be used effectively for a strong delaying action.

-

- South of the Sunabe hills, down to

the Uchitomari-Tsuwa line, the island narrows to 5,500 yards. The terrain

is essentially similar to that behind the Hagushi beaches, with heavily wooded

uplands and extensively terraced and cultivated valleys and lower slopes.

The hills and ridges are generally low except for some high peaks in the general

vicinity of Kuba on the east coast, from which observa-

- [10]

- OKINAWA'S LANDSCAPE in the south is marked by fields of grain and

vegetables,

- broken only by humps of coral, farmhouses, and villages. Navy plane

flying over such

- terrain is shown dropping supplies to the last fast-moving American

troops early in the campaign

-

- [11]

- VILLAGES ON OKINAWA consist of small clusters of houses surrounded

by vegetation-

covered stone and mud walls. Note camouflaged Japanese Army trucks

-

- [12]

- tion of the area is excellent. Roads

are adequate for light Japanese transport but not for the heavy strain of

American military traffic.

-

- On the east coast, the Katchin Peninsula

on the north and the Chinen Peninsula on the south extend into the ocean to

inclose the spacious fleet anchorage of Nakagusuku Bay, called by the American

troops "Buckner" Bay. A low coastal plain from one-fourth to one

mile wide runs along the shore of the bay from the Katchin Peninsula to Yonabaru.

At Yonabaru the plain extends inland to the west through an area of moderate

relief and joins another coastal flat extending northeastward from Naha. A

cross-island road follows this corridor and connects the two cities. Naha,

the capital of the island, with a population of 65,000, is Okinawa's chief

port and can accommodate vessels up to 3,000 tons. Southwest of the city,

on the Oroku Peninsula, was the Naha airfield, the most highly developed field

on the island.

-

- In the region north of the Naha-Yonabaru

corridor and in the vicinity of Shuri, the ancient capital of Okinawa, lies

the most rugged terrain in the southern part of the island. From the high

ground near Shuri and from many other vantage points in this area observation

is excellent to the north and south and over the coastal regions. At the highest

point the hills rise about 575 feet, but the lack of pattern, the escarpments,

steep slopes, and narrow valleys characteristic of the region make the major

hill masses ideal territory for defense. Many of the escarpments are sheer

cliffs without topsoil or vegetation. The low ground is filled with twisting

ridges and spotted with small irregular knolls, rendering observation difficult

and providing excellent locations for minor infantry and antitank positions.

The most prominent features of the region are the strong natural defensive

line of the Urasoe-Mura Escarpment, rising from the west coast above the Machinato

airfield and running for 4,500 yards across the island in a southeasterly

direction, and the chain of hills through Tanabaru and MinamiUebaru to the

east coast southwest of Tsuwa.

-

- South of the strong Shuri positions

the terrain is rough, but there are few large escarpments. There are some

broad valleys and an extensive road net which would facilitate troop movements.

The terrain in the southern end of the island consists of an extensive limestone

plateau, surrounded by precipitous limestone cliffs. The northern side of

the plateau is a 300-foot escarpment which rises vertically from the valley

floor in a jagged coral mass. On the top of the plateau major hills-Yuza-Dake

and Yaeju-Dake-cover all approaches from the north, east, and west. Along

the southeastern coast, much of the stretch from Minatoga to the eastern end

of the Chinen Peninsula consists of beaches.

- [13]

- These are dominated by the rolling

dissected terrace forming the body of the peninsula and by the high plateau

to the southwest.

-

- American Intelligence of the Enemy

- American knowledge of the enemy and

of the island of Okinawa was acquired slowly over a period of many months

and in the face of many difficulties. With Okinawa isolated from the world

by the Japanese, information of military value concerning this strategic inner

defense line of the Empire was scarce and difficult to obtain. Limited basic

intelligence was garnered from documents and prisoners captured on Pacific

island battlefields, from interrogation of former residents of the Ryukyus,

and from old Japanese publications. The great bulk of the data was obtained

through aerial photographic reconnaissance. This, however, was often incomplete

and inadequate, particularly for terrain study and for estimating enemy strength

and activity. The distance of the target from American air bases-1,200 nautical

miles-necessitated the use of B-29's and carrier planes for photographic missions;

the former afforded only high-altitude, small-scale coverage, while the latter

depended on the scheduling of carries strikes. The relatively large land masses

involved and the prevalence of cloud cover added to the difficulty of obtaining

the large-scale photographs necessary for detailed study of terrain and installations.14

-

- The target map prepared by American

intelligence represented all that was known of the terrain and the developed

facilities of the island. This map, scale 1 : 25,000, was based on aerial

photographs obtained on 29 September and 10 October 1944 and was distributed

about 1 March 1945. Incomplete coverage, varying altitudes of the planes,

and cloudiness over parts of the island at the time prevented clear delineation,

and certain portions of the map, including that of the high ground north of

Shuri, had either poor topographic detail or none at all. Additional photographic

coverage of the island was obtained on 3 and 22 January, 28 February, and

1 March 1945; that of 22 January was excellent for the proposed landing beach

areas. To supplement aerial photography a submarine was sent from Pearl Harbor

to take pictures of all Okinawa beaches. The submarine never returned.15

- [14]

- Hydrographic information was complete,

but its accuracy could not be checked until the target was reached. As the

data agreed with a captured Japanese map they were presumed to be accurate.

The most reliable information on the depth of the water over the reefs was

obtained from Sonne Strip photography and was made available to the troops

in March.16

-

- The first estimate of enemy strength,

made in October 1944, put the number of Japanese troops on Okinawa at 48,600,

including two infantry divisions and one tank regiment.17

In January 1945 this estimate was raised to 55,000, with the expectation that

the Japanese would reinforce the Okinawa garrison to 66,000 by 1 April 1945.

At the end of February, however, the January estimate was still entertained.

All these figures were based on interpretation of aerial photographs and on

the use of standard Japanese Tables of Organization: there was no documentary

evidence corroborating the estimate of the number of troops on the island.

18

-

- It was believed that the Japanese

had moved four infantry divisions to the Ryukyus during 1944. These were identified

as the 9th, 62d, 24th, and 28th Divisions. Army intelligence learned that

one division, perhaps the 9th, had been moved from Okinawa to Formosa in December

1944. In March 1945 American intelligence estimated that the Japanese forces

on Okinawa consisted of the following troops, which included 26 battalions

of infantry

| Headquarters 32d Army |

625 |

| 24th Division (triangular) |

15,000-17,000 |

| 62d Division (square) |

11,500 |

| 44th Independent Mixed Brigade |

6,000 |

| One independent mixed regiment |

2,500 |

| One tank regiment |

750 |

- One medium artillery

regiment, two mortar battalions, one anti-

- tank battalion, three

antitank companies, and antiaircraft

- units

|

5,875 |

| Air-ground personnel |

3,500 |

| Service and construction

troops |

5,000-6,000 |

| Naval-ground troops |

3,000 |

| Total |

53,000-56,000 |

-

- [15]

- It was considered possible that elements

of the 9th and 28th Divisions might also be present on Okinawa

proper. Enemy forces were known to be organized under the 32d Army,

commanded, it was thought, by General Watanabe, with headquarters at Naha.

Shortly before the landings the estimate of Japanese troops was raised to

65,000 on the basis of long-range search-plane reports of convoy movements

into Naha.19

-

- Calculations based on Japanese Tables

of Organization indicated that the enemy could be expected to have 198 pieces

of artillery Of 70-mm. or larger caliber, including twenty-four 150-mm. howitzers.20

The Japanese were presumed to have also about 100 antitank guns of 37-mm.

and 47-mm. caliber in addition to the guns carried on tanks. The tank regiment

on Okinawa had, according to Japanese Tables of Organization, 37 light and

47 medium tanks, but one estimate in March placed the total number of tanks

at 90. Intelligence also indicated that rockets and mortars up to 250 mm.

could be expected.21

-

- Aerial photographs disclosed three

main defense areas on Okinawa, centering in Naha, the Hagushi beaches, and

the Yonabaru-Nakagusuku Bay area on the east coast. Prepared positions for

four infantry regiments were noted along the bay; for one regiment, behind

the Hagushi beaches; and for one battalion, along the beaches at Machinato

above Naha. It was believed that a total of five or six battalions of troops

would be found in the northern part of Okinawa and le Shima and that two divisions

would be concentrated in southern Okinawa. The main strength of the Japanese

artillery was believed to be concentrated in two groups-one about two miles

east of Yontan airfield and the other about three miles due south of Shuri;

the probable presence of guns was deduced from the spoil which had been deposited

in front of cave or tunnel entrances on the slopes of ridges in a manner suitable

for gun emplacements.22

-

- At the end of March 1945 intelligence

indicated that there were four operational airfields on Okinawa at Naha, Yontan,

Kadena, and Machinato; the first two were the best. All were heavily defended

with numerous antiaircraft and dual purpose gun emplacements. The Yonabaru

strip, which had been in an initial stage of construction in October 1944,

was reported as having been aban-

- [16]

- doned by February 1945. Apparently

not intending to defend Ie Shima very determinedly, the Japanese, in the latter

part of March, were reported to have rendered the airfield there unusable

by digging trenches across the runways.23

Land-based enemy aircraft on Okinawa was not expected to constitute a danger;

the Americans fully expected that the airfields would be neutralized by the

time they invaded the island. It was reported on 29 March, however, that enemy

fighter and transport planes were being flown in at night to the Kadena airfield.

On 31 March no activity was observed on any of the Okinawa airfields. It was

constantly stressed that heavy enemy air attacks would probably be launched

from Kyushu, 350 miles to the north. The potential threat of small suicide

boats against shipping was also pointed out. 24

-

- Tenth Army believed that the most

critical terrain for the operation was the area between the Ishikawa Isthmus

and the Chatan-Toguchi line, particularly the high ground inland which dominates

the Hagushi beaches and the valley of the Bishi River. The enemy could defend

the beaches from prepared positions with one regiment, maintaining mobile

reserves in the hills north and south of the river. Other reserves could be

dispatched to the landing area within a few hours. It was expected that the

Japanese would wait until the night of L Day to move their artillery. Alerted

by American preliminary operations, they might have a division in position

ready for a counterattack on the morning of the landings. From terrain 3,000

yards inland that offered both cover and concealment, the Japanese could launch

counterattacks of division strength against both flanks of the landing area

simultaneously. If the landings were successful, the enemy's main line of

resistance, manned by a force of from nine to fifteen battalions, was expected

to be at the narrow waist of the island, from Chatan to Toguchi, south of

the landing beaches. 25

-

-

- The plan for the conquest of the Ryukyus

was in many respects the culmination of the experience of all previous operations

in the Pacific war. It embodied the lessons learned in the long course of

battle against the Japanese out-

- [17]

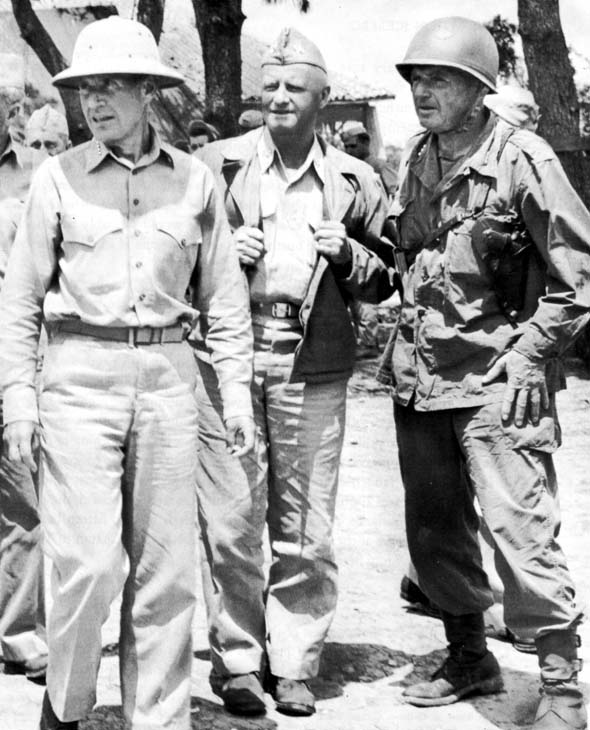

- AMERICAN COMMANDERS in Operation ICEBERG: Admiral Raymond A. Spruance,

- Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, and Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner.

-

- [18]

- posts in the Pacific-lessons of cooperation

and combined striking power of the services, of the technique of amphibious

operations, and of Japanese tactics and methods of meeting them. The plan

for ICEBERG brought together an aggregate of military power-men, guns, ships,

and planes that had accumulated during more than three years of total war.

The plan called for joint operations against the inner bastion of the Japanese

Empire by the greatest concentration of land, sea, and air forces ever used

in the Pacific.

-

- Basic Features of the Plan

- The immediate task imposed upon the

American forces by the terms of the general mission was the seizure and development

of Okinawa and the establishment of control of the sea and air in the Ryukyus.

The campaign was divided into three phases. The seizure of southern Okinawa,

including Keise Shima and islands in the Kerama Group, and the initiation

of the development of base facilities were to constitute the first phase.

In the next phase Ie Shima was to be occupied and control was to be established

over northern Okinawa. The third phase consisted of the seizure and development

of additional islands in the Nansei Shoto for use in future operations. The

target date of the operation was set at 1 March 1945. 26

-

- Planning began in October 1944. The

general scheme for Operation ICEBERG was issued in the fall of 1944 by Admiral

Nimitz as Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPOA). The strategic

plan outlined was based on three assumptions. First, the projected campaign

against Iwo Jima would have progressed to such an extent that naval fire-support

and close air-support units would be available for the assault on Okinawa.

Second, the necessary ground and naval combat units and assault shipping engaged

in the Philippines would be released promptly by General MacArthur for the

Okinawa campaign. Third, preliminary air and naval operations against the

enemy would ensure control of the air in the area of the target during the

operation.27

-

- Air superiority was the most important

factor in the general concept of the operation as outlined by Admiral Nimitz's

staff. The CINCPOA planners believed that American air attacks on Japan, from

carriers and from airfields in the Marianas, combined with the seizure of

Iwo Jima, would force a concentration of enemy air strength around the heart

of the Empire-on the home islands, Formosa, the China coast, and the Ryukyus.

From these bases, strong

- [19]

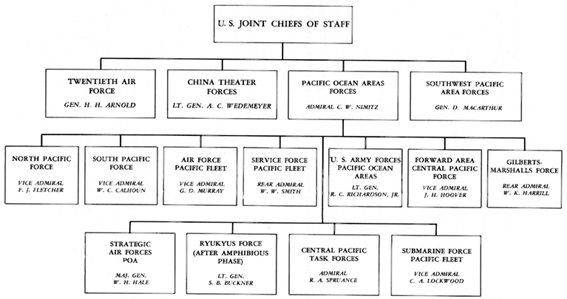

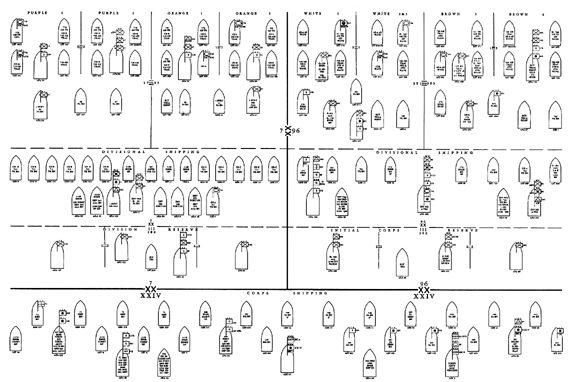

- Organization of Allied Forces for the Ryukyus Campaign,

- January 1945

-

- Source: Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas,

Operations in the

- Pacific Ocean Areas, April 1945, Plate I, opp. p. 76 (with adaptations).

-

- [20]

- and continuous air attacks would be

made against the forces invading the Ryukyus. It would be necessary, therefore,

to neutralize or destroy enemy air installations not only at the target but

also at the staging areas in Kyushu and Formosa. All available carrier- and

land-based air forces would be called on to perform this task and give the

Americans the control of the air required in the area of operations. On Okinawa

itself, the scheme of maneuver of the ground troops would be such as to gain

early use of airfields that would enable landbased planes to maintain control

of the air in the target area. Control of the sea was to be maintained by

submarine, surface, and air attacks on enemy naval forces and shipping. 28

-

- The American Forces

- The isolation of Okinawa was to be

effected with the aid of land-based air forces of commands outside the Pacific

Ocean Areas (POA). Planes from the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) were to engage

in searches and continuous strikes against Formosa as soon as the situation

on Luzon permitted. Twentieth Air Force B-29's from China and the Marianas

were to bomb Formosa, Kyushu, and Okinawa during the month preceding the landings.

The China-based XX Bomber Command was to concentrate on Formosa, while the

XXI Bomber Command from the Marianas would attack Okinawa and then shift to

Kyushu and other vulnerable points in the home islands during the fighting

on Okinawa. The Fourteenth Air Force was to conduct searches along the China

coast and also, if practicable, bomb Hong Kong.29

-

- All the forces in Admiral Nimitz's

command were marshaled in support of the ICEBERG Operation. (See Chart 1.)

The Strategic Air Forces, POA, was assigned the task of neutralizing enemy

air bases in the Carolines and the Bonins, of striking Okinawa and Japan when

practicable, and of providing fighter cover for Twentieth Air Force bombing

missions against Japan. The Commander, Forward Areas Central Pacific, was

to use his naval air strength to provide antisubmarine coverage, neutralize

bypassed enemy bases, and, in general, furnish logistic support. Provision

of intelligence on enemy naval units and interdiction of the sea approaches

from Japan and Formosa were the tasks of the Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet.

The enemy was to be contained in the North Pacific Area, and the lines of

communication were to be secured in the Marshalls-Gilberts area. Logistic

support was to be provided by General Rich-

- [21]

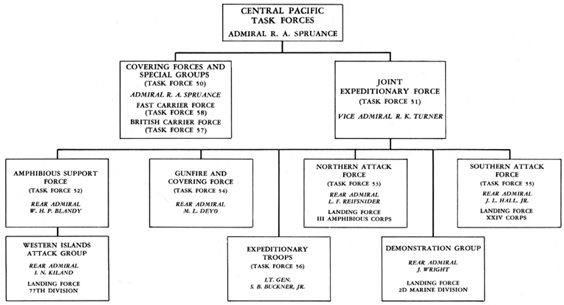

- Organizations of Central Pacific Task Forces for the Ryukyus Campaign,

- January 1945

-

- Source: Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas,

Operations in the

- Pacific Ocean Areas, April 1945, Plates I and II, opp. p. 76 (with adaptations).

-

- [22]

- ardson's United States Army Forces,

POA (USAFPOA), the Air and Service Forces, Pacific Fleet, and the South Pacific

Force. All the armed forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas, from the West Coast

to Ulithi and from New Zealand to the Aleutians, were directed to support

the attack on Okinawa.30

-

- The principal mission in seizing the

objective was assigned to a huge joint Army-Navy task force, known as the

Central Pacific Task Forces and commanded by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance,

Commander of the Fifth Fleet. (See Chart II.) Admiral Spruance's forces consisted

of naval covering forces and special groups (Task Force 50), which he personally

commanded, and a joint Expeditionary Force (Task Force 51), commanded by Vice

Admiral Richmond K. Turner, Commander, Amphibious Forces Pacific Fleet. General

Buckner, Commanding General, Tenth Army, was to lead the Expeditionary Troops

(Task Force 56) under Admiral Turner's direction.31

-

- Command relationships prescribed for

the operation differed in some respects from those in previous operations

against island positions remote from Japan. Because the campaign would entail

prolonged ground combat activities by a field army on a large island close

to the enemy's homeland, it was necessary to define clearly the relationships

between Army and Navy commanders for the successive phases of the operation.

Admiral Nimitz accordingly provided that initially the chain of command for

amphibious operations would be Admiral Spruance, Admiral Turner, General Buckner.

However, when Admiral Spruance determined that the amphibious phases of the

operation had been successfully completed, General Buckner was to assume

command of all forces ashore. He was thereafter to be directly responsible

to Admiral Spruance for the defense and development of the captured positions.

In time, Admiral Spruance would be relieved by Admiral Nimitz of these responsibilities,

and General Buckner would take over complete command of the forces in the

Ryukyus. As Commander, Ryukyus Force, a joint task force of ground, air, and

naval garrison troops, he would be responsible only to CINCPOA for the defense

and development of the newly won bases and for the protection of the sea areas

within twenty-five miles.32

-

- Admiral Spruance, as commander of

Task Force 50, had at his disposal Vice Admiral Mitscher's Fast Carrier Force

(Task Force 58), a British Carrier Force

- [23]

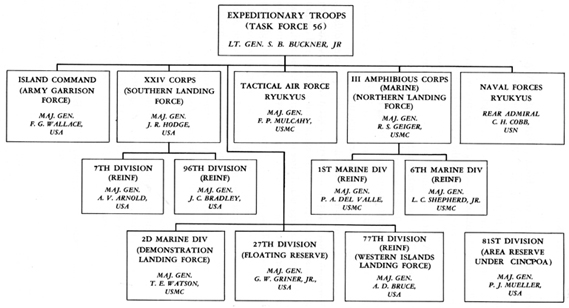

- Organization of Expeditionary Troops for the Ryukyus Campaign,

- January 1945

- Source: Commander Task Force 51, Commander Amphibious Forces, U. S.

Pacific Fleet, Report on Okinawa Gunto Operations from February 17 May

to 17 May 1945, Part 1, pp. 2-4; Tenth Army Action Report Ryukyus, 26

March to 30 June 1945, Ch. 2; Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and

Pacific Ocean Areas, Operation in the pacific Ocean Areas, April 1945.

- [24]

- (Task Force 57), special task groups

for aerial search and reconnaissance and antisubmarine warfare, and fleet

logistic groups. Task Force 58 had a major share of the mission of neutralizing

Japanese air strength. Its fast carriers were to strike Kyushu, Okinawa, and

adjacent islands in the middle of March, to remain in a covering position

east of the target area during the week preceding the invasion, to support

the landings with strikes and patrols, and to be prepared for further forays

against Kyushu, the China coast, or threatening enemy surface forces. The

British carriers, the first to participate in Pacific naval actions with the

American fleet, were given the task of neutralizing air installations on the

Sakishima Group, southwest of the Ryukyus, during the ten days before the

landings. 33

-

- The Joint Expeditionary Force (Task

Force 51) was directly charged with the capture and development of Okinawa

and other islands in the group. It was a joint task force of Army, Navy, and

Marine units and consisted of the Expeditionary Troops (Task Force 56-see

Chart III), shipping to transport them, and supporting naval and air units.

Direct naval and air support for Task Force 51 was to be furnished by its

Amphibious Support Force (Task Force 52), made up of escort carriers, gunboat

and mortar flotillas, mine sweepers, and underwater demolition teams, and

by the Gunfire and Covering Force (Task Force 54) of old battleships, light

and heavy cruisers, destroyers, and destroyer escorts. The transports and

tractor units of the Northern Attack Force (Task Force 53) and Southern Attack

Force (Task Force 55) were to land the ground troops in the main assault on

the Okinawa beaches, while a number of task groups were assigned the task

of transporting the troops for subsidiary landings and the floating and area

reserves. Task Force 51 also included a transport screen, a service and salvage

group, and several specialized naval units. 34

-

- The troops who would assault the objectives

constituted a field army, the Tenth Army, which had been activated in the

United States in June 1944 and shortly thereafter had opened headquarters

on Oahu. General Buckner formally assumed command in September 1944, having

come to the new assignment from the command of the Alaskan Department, where

for four years he had been organizing the American defenses in that area.

His new staff included many officers who had served with him in Alaska as

well as some from the European Theater of Operations. The major components

of Tenth Army were

- [25]

- XXIV Army Corps and III Amphibious

Corps (Marine). The former consisted of the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions

and was commanded by Maj. Gen. John R. Hodge, a veteran leader of troops who

had met and defeated the Japanese on Guadalcanal, New Georgia, Bougainville,

and Leyte. III Amphibious Corps included the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions

and was headed by Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger, who had successfully directed Marine

operations on Bougainville and Guam. Three divisions, the 27th and 77th Infantry

Divisions and the 2d Marine Division, were under the direct control of Tenth

Army for use in special operations and as reserves. The area reserve, the

81st Infantry Division, was under the control of CINCPOA. Also assigned to

Tenth Army for the purpose of defense and development of the objectives were

a naval task group, the Tactical Air Force, and the Island Command. 35

-

- A total of 183,000 troops was made

available for the assault phases of the operation.36

About 154,000 of these were in the seven combat divisions, excluding the 81st

Division, which remained in New Caledonia; all seven divisions were heavily

reinforced with tank battalions, amphibian truck and tractor battalions, joint

assault signal companies, and many attached service units. The five divisions

committed to the initial landings totaled about 116,000. The 1st and 6th Marine

Divisions, with 26,274 and 24,356 troops, respectively, each carried an attached

naval construction battalion and about 2,500 replacements in addition to their

other supporting combat and service units. The reinforced 7th, 77th, and 96th

Divisions averaged nearly 22,000 men per division but each was about 1,000

understrength in organic infantry personnel. The 27th, a reserve division,

was reinforced to a strength of 16,143 but remained nevertheless almost 2,000

understrength organically. The 2d Marine Division, also in Army reserve, numbered

22,195.37

(See Appendix C, Table No. 4)

-

- Tenth Army, as such, had never directed

any campaigns, but its corps and divisions had all been combat-tested before

the invasion of the Ryukyus. XXIV Corps had carried out the conquest of Leyte,

and III Amphibious Corps had captured Guam and Peleliu. The 7th Division had

seen action on Attu, Kwajalein, and Leyte, the 77th on Guam and Leyte, and

the 96th on Leyte. The 27th had taken part in the battles for the Gilberts

and Marshalls and for

- [26]

- Saipan. The 1st Marine Division had

been one of the first to see action in the Pacific, on Guadalcanal, and had

gone through the campaigns of Western New Britain and Peleliu. The 6th Marine

Division had been activated late in 1944, but its regiments were largely made

up of seasoned units that had fought on Guam, the Marshalls, and Saipan. The

ad Marine Division had participated in the fighting on Guadalcanal, Tarawa,

Saipan, and Tinian.

-

- Plan for the Capture of Okinawa

- Using the CINCPOA Toint Staff Study

as a basis, each of the major commanders prepared his plans and issued his

operation orders. Although each plan and operation order was derived from

that of the next superior echelon, planning was always concurrent. The joint

nature of the operation also required extensive coordination of the three

services in all operational and logistical problems. Joint conferences thrashed

out problems of troop lists, shipping, supplies, and strategy. Corps and task

force commanders worked together on the plans for amphibious operations. Corps

and division staffs were consulted and advised by Army for purposes of orientation

and planning. To ensure inter-service coordination, Navy and Marine officers

were assigned to work with Tenth Army general and special staff sections.38

In some cases planning was facilitated by utilizing the results of work on

other operations. Thus the naval staff developing the gunfire support plans

was able to use the operations at Iwo Jima to test and strengthen the general

command and communications framework, which was generally similar for both

operations; in the same way Tenth Army logistical planners took advantage

of their work on the canceled Formosa operation, adapting it to the needs

of the Okinawa campaign.39

-

- Out of these planning activities came

extremely important decisions that modified and expanded the scope of proposed

operations. Tenth Army found it necessary to enlarge the troop list by about

70,000 to include greater numbers of supporting combat elements and service

units. Its staff presented and supported a plan for initial assault landings

on the west coast of Okinawa, just north and south of Hagushi, as the most

feasible logistically and as consonant tactically with the requirements of

CINCPOA. The naval staff insisted on the necessity of a sustained week-long

naval bombardment of the target and on the consequent need for a protected

anchorage in the target area where the fleet units could refuel and resupply.

As a result it was decided to capture the Kerama Islands

- [27]

- just west of Okinawa, a week before

the main landings, and the 77th Division was assigned this task. At the suggestion

of Admiral Turner a landing was to be feinted on the eastern coast of the

island, and the 2d Marine Division was selected for this operation. The commitment

of these two reserve divisions impelled Tenth Army to secure the release of

the area reserve division to the Expeditionary Troops, and the 27th Division

was designated the floating reserve. In its place, as area reserve, the first

Division was ordered to stand by in the South Pacific. Finally, CINCPOA was

twice forced to set back the target date because delays in the Luzon operation

created difficulty in maintaining shipping schedules and because unfavorable

weather conditions appeared likely in the target area during March. L Day

(landing day) was set for 1 April 1945.40

-

- As finally conceived, the plan for

the capture of Okinawa gave fullest opportunity for the use of the mobility,

long range, and striking power of combined arms. After the strategic isolation

of Okinawa had been effected by land- and carrier-based aircraft, the amphibious

forces were to move forward to the objective. Task Force 52 (the Amphibious

Support Force) and Task Force 54 (the Gunfire and Covering Force), assisted

by the fast carriers of Task Force 58, were to begin operations at Okinawa

and the Kerama Group on L minus 8 (24 March). They were to destroy the enemy

defenses and air installations by naval gunfire and air strikes, clear the

waters around the objective and the beaches of mines and other obstacles,

and provide cover and protection against hostile surface and air units to

ensure the safe and uninterrupted approach of the transports and the landings

of the assault troops. After the landings they were to furnish naval support

and air cover for the land operations.41

-

- Mine sweepers were to be the first

units of the Amphibious Support Force to arrive in the target area. Beginning

on L minus 8, they were to clear the way for the approach of the bombardment

units and then to sweep the waters in the landing and demonstration areas

to the shore line.42

Underwater demolition teams were to follow the mine sweepers, reconnoiter

the beaches, and demolish beach obstacles.43

-

- Naval gunfire was to support the capture

of Okinawa by scheduled destructive bombardment in the week before the landings,

by intensive close support

- [28]

- of the main and subsidiary landings

and the diversionary feint, and thereafter by delivering call and other support

fires. The fire support ships with their 5- to 16-inch guns were organized

into fire support units, each consisting of 2 old battleships, 2 or 3 cruisers,

and 4 or 5 destroyers, that were to stand off the southern part of the island

in accordance with definite areas of responsibility. In view of the size of

the objective and the impossibility of destroying all targets, fire during

the prelanding bombardment was to be laid on carefully selected targets; the

principal efforts were to be directed to the destruction of weapons threatening

ships and aircraft and of the defenses opposing the landings. Profitable targets

were at all times to be sought by close observation, exploratory firing, and

constant evaluation of results. Covering fires were to be furnished in conjunction

with fire from gunboats and mortar boats in support of mine-sweeping operations

and beach demolitions.44

-

- On L Day, beginning at 0600, the naval

guns were to mass their fires on the beaches. Counterbattery and deep supporting

fires were to destroy the defense guns and keep enemy reinforcements from

moving up to oppose the landings. As the assault waves approached the beaches,

the fires of the big guns would lift to targets in critical areas inland and

to the exterior flanks of the troops. Mortar boats and gunboats were to lead

the boat waves to the shore, delivering mortar and rocket fire on the beaches.

All craft would begin 40-mm. fire on passing the line of fire support ships

and would fire at will until H Hour.45

After the landings scheduled fire on areas 1,000 yards inland and on the flanks

would be continued, but top priority would be given to call fires in direct

support of the assault elements.46

-

- All scheduled bombardments until H

minus 35 minutes were to be under control of the commander of Task Force 52.

After that time, because of the size of the landing forces and the extent

of the beaches, the commanders of the Northern and Southern Attack Forces

would assume control of the support of their respective landing forces. The

commander of Task Force 51 was to remain responsible for the general coordination

as well as the actual control of bombardment in the Army zone. By 1500 each

day he would allocate gunfire support vessels for the succeeding twenty-four

hours in accordance with approved requests from Army and Corps.47

- [29]

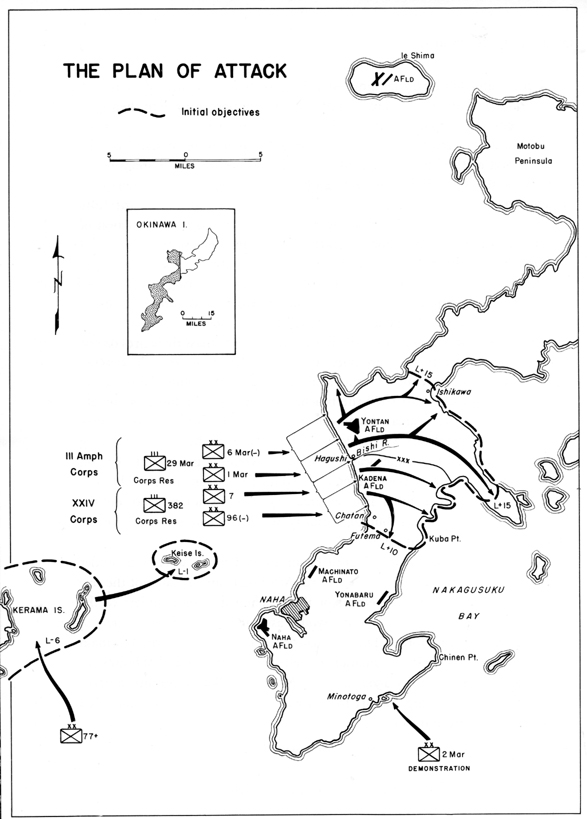

- MAP NO. 3

- [30]

- Air support was to be provided largely

by the fast carriers of Task Force 58 and by the escort carriers of Task Force

52. The fast carriers were for the first time to be available at the target

area for a prolonged period to furnish support and combat air patrols. They

were to cover mine-sweeping operations, hit targets on Okinawa which could

not be reached by naval gunfire, destroy enemy defenses and air installations,

and strafe the landing beaches. The escort carriers would provide aircraft

for direct support missions, antisubmarine patrols, naval and artillery gunfire

spotting, air supply, photographic missions, and the dropping of propaganda

leaflets. After L Day additional support was to be furnished by seaplane squadrons

based on the Kerama Islands and by the shorebased Tactical Air Force of the

Tenth Army.48

The latter was eventually to be responsible for the air defense of the area,

being charged with gaining the necessary air superiority and giving tactical

support to the ground troops.49

-

- Provision was made for the careful

coordination of all naval gunfire, air support, and artillery both in the

assault and in the campaign in general. Target information centers, to be

established at army, corps, and division levels, would collect and disseminate

data on all targets suitable for attack by the respective arms and keep a

record of attacks actually carried out. In addition, at every echelon, from

battalion to army, representatives of each support arm-artillery, naval gunfire,

and air-were to coordinate the use of their respective arms for targets in

their zones of action and advise their commanders on the proper employment

of the various types of supporting fires. Requests for support would thus

be coordinated and screened as they passed up through the various echelons

for approval.50

-

- Under cover of the sustained day and

night attacks by the naval and air forces, the first phase of the campaign-the

capture of the Kerama and Keise Islands and of the southern part of Okinawa-was

to begin. On L minus 6, the Western Islands Attack Group was to land the reinforced

77th Division on the Kerama Islands. The seizure of these islands was designed

to give the joint Expeditionary Force, prior to the main assault on Okinawa

proper, a base for logistic support of fleet units, a protected anchorage,

and a seaplane base. Two regimental combat teams were to land on several of

the islands simultaneously and to proceed from the southeast end of the group

to the northeast by island-

- [31]

- hopping maneuvers, capturing Keise

Island by L minus 1. All hostile coastal defense guns that could interfere

with the construction of the proposed naval bases were to be destroyed. Organized

enemy forces would be broken up without attempting to clear the islands of

snipers. Two battalions of 155-mm. guns were to be emplaced on Keise in order

to give artillery support to the landings on the coast of Okinawa. Then, after

stationing a small garrison force in the islands, the division would reembark

and be prepared to execute the Tenth Army's reserve plans, giving priority

to the capture of Ie Shima 51

(See Map No. 3.)

-

- While the 77th Division was taking

the lightly held Kerama Islands, the preliminary operations for softening

up Okinawa would begin; they would mount in intensity as L Day approached.

Beginning on 28 March fire support units would close in on the island behind

the mine sweepers and demolition teams. The Northern and Southern Attack Forces

would arrive off the west coast early on L Day and land their respective ground

forces at H Hour, tentatively set for 0830. III Amphibious Corps would land,

two divisions abreast, on the left flank, north of the town of Hagushi at

the mouth of the Bishi River XXIV Corps would land, two divisions abreast,

on the right flank, south of Hagushi. The four divisions in landing would

be in the following order from north to south; 6th Marine Division, 1st Marine

Division, 7th Division; and 96th Division. The two corps were then to drive

across the island in a coordinated advance. The 6th Marine Division was first

to capture the Yontan airfield and then to advance to the Ishikawa Isthmus,

the narrow neck of the island, securing the beachhead on the north by L plus

15. The 1st Marine Division was to head across the island and drive down the

Katchin Peninsula on the east coast. South of the Corps' boundary, which ran

eastward from the mouth of the Bishi, the 7th Division would quickly seize

the Kadena airfield and advance to the east coast, cutting the island in two.

The 96th was required initially to capture the high ground commanding its

beaches on the south and southeast; then it was to move rapidly down the coastal

road, capture the bridges near Chatan, and protect the right of the Corps.

Continuing its attack, it was to pivot on its right flank to secure the beachhead

on the south by L plus 10 on a line running across the isthmus below Kuba

and Futema.52

-

- The choice of the beaches north and

south of Hagushi for the initial assault was made after a study by Tenth Army

of all the landing beaches in southern

- [32]

- Okinawa and a survey of several plans

of action. The various plans were weighed in the light of the requirements

of the CINCPOA Joint Staff Study and considerations of tactical and logistical

feasibility. The preferred plan was finally chosen for a number of reasons.

First, it would secure the necessary airfields by L plus 5. Second, it would

provide the unloading facilities to support the assault. The Hagushi beaches

were considered the only ones capable of handling sufficient tonnage to sustain

a force of two corps and supporting troops, and this seemed to outweigh the

disadvantages of not providing for the early capture of the port of Naha and

the anchorage in Nakagusuku Bay. Third, the plan would result in separating

the enemy forces. Fourth, it would concentrate the troops on one continuous

landing beach opposite the point where the greatest enemy resistance was expected.

Fifth, it would use the terrain least advantageous for enemy resistance to

the landings. Finally, it would permit maximum fire support of the assault.53

-

- The scheme of maneuver was designed

to isolate the initial objective, the southern part of the island, by seizing

the Ishikawa Isthmus, north of the landing beaches, to prevent enemy reinforcement

from that direction. At the same time the establishment of a general east-west

line from Kuba on the south would prevent reinforcement from the south. Thereafter,

the attack was to be continued until the entire southern part of the island

was occupied.54

Ground commanders hoped that, for the first time in the Pacific, maneuver

could be used to the utmost. The troops would cut across the island quickly,

move rapidly to the south, break up the Japanese forces into small segments,

bypass strong points, and mop up at leisure.55

-

- While the troops were landing on the

west coast, the 2d Marine Division would feint landings on the southeast coast.

This demonstration, scheduled for L Day and to be repeated on L plus 1, would

be as realistic as possible in order to deceive the enemy into believing that

landings would be made there as well as on the Hagushi beaches. After the

demonstration the division would be prepared to land on the Hagushi beaches

in support of the assault forces.56

-

- The 27th Division, as floating reserve,

was to arrive at Ulithi not later than L plus 1 and be on call of the Commander,

Joint Expeditionary Force. It was

- [33]

- to be prepared to seize the islands

off the east coast of Okinawa and then to land on that coast in support of

XXIV Corps.57

-

- In case the preferred plan for landing

on the west coast proved impracticable, an alternate plan was to be used.

In this plan, the capture of the Kerama Islands was to be followed by a similar

sweep through the small islands east of southern Okinawa that guarded the

entrance to Nakagusuku Bay. On L Day two Marine divisions would land on the

southeast coast of Okinawa, between Chinen Point and the town of Minatoga.

During the next three days the marines were to seize high ground in the area

in order to support a landing by two divisions of XXIV Corps on the lower

part of Nakagusuku Bay, between Kuba and Yonabaru. Although the alternate

plan met most of the requirements for a successful landing operation, it was

distinctly a second choice because it would allow the enemy reserves to offer

maximum opposition to the second landings and would require a prolonged assault

against all the enemy forces on the island to complete the first phase of

the mission.58

-

- Psychological Warfare and Military

Government

- Despite general skepticism as to the

effectiveness of psychological warfare against the Japanese,59

an attitude which resulted from its failure in many previous operations, the

American plan called for an intensive effort to weaken the enemy's will to

resist. Intelligence agencies prepared 5,700,000 leaflets to be dropped over

Okinawa from carrier planes. More millions of leaflets were to be printed

at the target and scattered over specific areas by bombs and shells. Tanks

with amplifiers, an airplane with an ultraloud speaker, and remotely controlled

radios dropped behind enemy lines would also tell the enemy why and how he

should surrender.60

-

- The plans for psychological warfare

were also directed toward influencing the Okinawans, and in this connection

there was greater optimism. Because the Okinawans were of a different stock

and culture from the Japanese, and had been treated by their rulers as inferiors

rather than as elements to be assimilated to Japanese nationalism and militarism,

it was hoped that the civilians would not be as hostile, or at any rate as

fanatical, as the Japanese.

- [34]

- The Okinawans also presented the American

planners with the problem of military government. The problem was twofold-that

of removing the Okinawans from the front lines and that of caring for them;

it was necessary to handle the problem in such a way as to facilitate military

operations and to make available to the occupying forces the labor and economic

resources of the areas. Approximately 300,000 natives lived in southern Okinawa;

thousands of others were in the north and on near-by islands. Never before

in the Pacific had Americans faced the task of controlling so many enemy civilians.

-

- Basic responsibility for military

government in the conquered Japanese islands devolved on the Navy, and Admiral

Nimitz was to assume the position of Military Governor of the Ryukyus. However,

in view of the fact that most of the garrison forces were Army troops, Admiral

Nimitz delegated the responsibility to General Buckner. The latter planned

to control military government operations during the assault phase through

his tactical commanders; corps and division commanders were made responsible

for military government in the areas under their control and were assigned

military government detachments whose mission was to plan and organize civilian

activities behind the fighting fronts. As the campaign progressed and increasing

numbers of civilians were encountered, teams attached to military government

headquarters of Tenth Army would assume charge, organize camps, and administer

the program on an island-wide basis. During the garrison phase the Island

Commander, on order of General Buckner, would exercise command over all military

government personnel. Maj. Gen. Fred C. Wallace would act through a Deputy

Commander for Military Government, Brig. Gen. W. E. Crist 61

-

- The major problem of Military Government

was to feed and provide emergency medical care for the approximately 300,000

civilians who were expected to be within the American lines by L plus 40.

Each of the combat divisions mounted out with 70,000 civilian rations of such

native staples as rice, soy beans, and canned fish and also with medical supplies.

Military Government personnel would land in the wake of assault units to handle

a huge "disaster relief" program. Additional supplies of all kinds

were to be included in the general maintenance shipments.62

- [35]

-

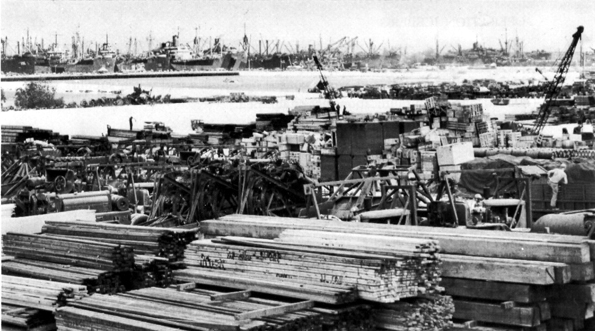

- Organizing the Supply Line

- The planning and execution of ICEBERG

presented logistical problems of a magnitude greater than any previously encountered

in the Pacific. For the assault echelon alone, about 183,000 troops and 747,000

measurement tons of cargo were loaded into over 430 assault transports and

landing ships at 11 different ports, from Seattle to Leyte, a distance of

6,000 miles. (See Appendix C, Tables Nos. 4 and 5.) After the landings, maintenance

had to be provided for the combat troops and a continuously increasing garrison

force that eventually numbered 270,000. Concurrently, the development of Okinawa

as an advanced air and fleet base and mounting area for future operations

involved supply and construction programs extending over a period of many

months subsequent to the initial assault. Close integration of assault, maintenance,

and garrison shipping and supply was necessary at all times.63

-

- Factors of distance dominated the

logistical picture. Cargo and troops were lifted on the West Coast, Oahu,

Espiritu Santo, New Caledonia, Guadalcanal, the Russell Islands, Saipan, and

Leyte, and were assembled at Eniwetok, Ulithi, Saipan, and Leyte. The closest

Pacific Ocean Area bases were at Ulithi and the Marianas, 5 days sailing time

to Okinawa (at 20 knots). The West Coast, which furnished the bulk of resupply,

was 6,250 nautical miles away, Or 26 days' sailing time. Allowing 30 days

to prepare and forward the requisitions, 60 days for procurement and loading

on the West Coast, and 30 days for sailing to the target, the planners were

faced with a 1120-day interval between the initiation of their calculations

and the arrival of supplies. This meant in practice that requisitioning had

to be started before a Troop Basis had been fixed and the details of the tactical

plans worked out. Distance, moreover, used up ships and compelled the adoption

of a schedule of staggered supply shipments, or "echelons," as well

as a number of other improvisations. Mounting the troops where they were stationed,

in the scattered reaches of the Pacific Ocean and Southwest Pacific Areas,

required close and intricate timing to have them at the target at the appointed

moment.64

-

- Broad logistic responsibilities for

the support of ICEBERG were assigned by Admiral Nimitz to the various commanders

chiefly concerned. Admiral Turner, as commander of the Amphibious Forces Pacific

Fleet, furnished the

- [36]

- shipping for the assault troops and

their supplies, determined the loading schedules, and was responsible for

the delivery of men and cargo to the beaches. General Buckner allocated assault

shipping space to the elements of his command and was responsible for landing

the supplies and transporting them to the dumps. The control of maintenance

and garrison shipping, which was largely loaded on the West Coast, was retained

by CINCPOA. Responsibility for both the initial supply and the resupply of

all Army troops was assigned to the Commanding General, Pacific Ocean Areas,

while the Commanders, Fleet Marine Force, Service Force, and Air Force of

the Pacific Fleet were charged with logistic support of Marine, Navy, and

naval aviation units. The initial supplies for the troops mounting in the

South Pacific and the Southwest Pacific were to be furnished by the commanders

of those areas.65

-

- The first phase of supply planning

involved the preparation of special lists of equipment required for the operation,

which included excess Tables of Equipment items, equipment peculiar to amphibious

operations, and base development materials. Such lists, or operational projects

as they were known, had been prepared for the projected Formosa operation;

when this was canceled the projects were screened and reduced to meet the

needs of ICEBERG.66

-

- At a very early stage in the planning

it became evident that there was a shortage of available shipping. The number

of combat and service troops included in the initial Troop Basis far exceeded

the capacity of allocated shipping. As a result, tonnage had to be reduced

for some units while other units were eliminated entirely from the assault

echelon and assigned space in the next echelon. Later, in January 1945, it

became apparent that there was still not enough shipping space in the assault

echelon to transport certain air units and base development materials designed

for early use. It was necessary to request CINCPOA to increase the over-all

allocation of LST's and LSM's, as well as to curtail cargo tonnage and provide

for the quick return of LST's to Saipan to load eight naval construction battalions.67

-

- Providing the assault troops with

their initial supplies was not a difficult problem as generally there were

sufficient stocks on hand at each of the mounting areas. When the assault

units embarked, they took with them a 30-day supply of rations, essential

clothing and equipment, fuel, and medical and construction

- [37]

- supplies. Initial ammunition quotas

consisted of five CINCPOA units of fire.68

On Leyte, XXIV Corps found that SWPA logistics agencies did not have sufficient

rations on hand to supply it as required, and the shortage was overcome by

having the Corps joined at Okinawa by two LST's loaded with rations from Tenth

Army reserve stocks in the Marianas.69

-

- Equipment issued to the troops included

weapons and instruments of war never before used against the Japanese.

New-type flame-thrower tanks, with an increased effective range and a larger

fuel capacity, were available for the invasion. Each division was issued 110

sniperscopes and 140 snooperscopes, devices for seeing in the dark by means

of infrared radiation; the former were mounted on carbines and permitted accurate

night firing, while the latter were on hand-held mounts and could be used

for night observation and signaling. Army artillery and antiaircraft units

used proximity (VT) fuzes over land areas for the first time in the Pacific.

During the campaign tests were conducted with a new mortar-locating device,

the Sound Locator Set GR-6, and the 57-mm.. and 75-mm. recoilless rifles and

4.2-inch recoilless mortars.70

-

- Supplies to maintain the troops at

the target were scheduled to arrive twenty-one shipments from the West Coast.

Loaded ships were to sail from Pacific ports at 10-day intervals, beginning

on L minus 40 (20 February 1945), and to arrive at the regulating stations

at Ulithi and Eniwetok beginning , L minus 5, there to await the call of General

Buckner. These maintenance; shipments, planned to provide automatic resupply

until L plus 210 (31 October 1945), were based on the estimated population

build-up at the scheduled time of arrival. The principal emergency reserves

were kept at Saipan and Guan. 71

-

- The main logistical task of the operation,

in Admiral Nimitz's opinion, v. the rapid development of air and naval bases

in the Ryukyus to support further operations against Japan. The Base Development

Plan for Okinawa, published by CINCPOA, provided for the construction of eight

airfields on Okinawa, two of which were to be operational by L plus 5, a seaplane

base, an advanced fleet.

- [38]

- base at Nakagusuku Bay, and the rehabilitation

of the port of Naha to accommodate support shipping. Base development responsibilities

also included immediate support of the assault by the early construction of

tank farms for the bulk storage of fuel and for the improvement of waterfront

unloading facilities and of roads. Later a large construction program was

planned that included roads, dumps, hospitals, communications facilities,

water supply systems, and housing and recreational facilities. A plan for

the development of Ie Shima as an advanced air base was also prepared.72

-

- General Buckner was charged with the

responsibility for base development in the Ryukyus. Assigned to Tenth Army

for the execution of the Base Development Plan was the Island Command Okinawa,

or Army Garrison Force, with Maj. Gen. Fred C. Wallace in command. Some of

the Island Command troops were to land in the assault echelon and to provide

logistic support for the assault troops during and immediately after the landings.

At the conclusion of the amphibious phase, the Island Command was to act as

Tenth Army's administrative and logistical agency, operating in effect as

an Army service command and an advanced section of the communications zone.

As such, it was to be in charge of the base development program as well as

of the garrisoning and defense of the captured positions. Garrison troops

and base development materials were scheduled to arrive at Okinawa in seventeen

echelons. These were based primarily on the unloading capacity of the Hagushi

beaches; the tonnage in each echelon was kept within the estimated discharge

capacity between the arrivals of the echelons. Most of this garrison shipping

was loaded on the West Coast and Oahu, but some originated in the South Pacific

and the Marianas.73

-

- Training and Rehearsal of Troops

- The great distances that separated

the elements of its command, together with the limited time available, precluded

combined training or rehearsal by Tenth Army of the maneuver which would land

two corps abreast on a hostile shore. To the extent that circumstances permitted,

however, the scattered units of the Tenth Army engaged in individual training,

combined-arms training, and special training in amphibious, cave, and mountain