- Chapter II:

-

- Invasion Of The Ryukyus

-

- Operations preliminary to the

landing on Okinawa were as protracted and elaborate as the tactical and

logistical planning. From October 1944 to April 1945 American forces

from the Pacific Ocean Areas, the Southwest Pacific Area, and the China

Theater conducted an intensive campaign to neutralize Japanese air and

naval strength.1

In the last week of March, while the Kerama Islands

were being seized, the Navy concentrated on a furious bombardment of the

main target. Before the troops for the assault mounted out American

forces had invaded Luzon and Iwo Jima.

-

-

- The first attack on Okinawa was

made by Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher's Fast Carrier Task Force,

operating as part of the Third Fleet, in the preliminary operations for

the landings on Leyte. Nine carriers, 5 fast battleships, 8 escort

carriers, 4 heavy cruisers, 7 light cruisers, 3 antiaircraft cruisers,

and 58 destroyers arrived off Okinawa early on 10 October. Admiral

Mitscher made every effort to achieve surprise. The force followed the

track of bad weather caused by a typhoon moving toward Okinawa from the

southeast. A smaller force of cruisers and destroyers made a

diversionary attack on Marcus Island, 1,500 miles to the east, in such a

way as to simulate a large force. Aircraft based on the Marianas

intensified attacks on Iwo Jima, to hamper searches from that direction,

and flew interdiction patrols ahead of the Third Fleet forces.

-

- Wave after wave of carrier

planes swept over Okinawa shortly after dawn of 10 October. The first

strikes bombed, rocketed, and strafed airfields at Yontan, Kadena, le

Shima, and Naha. Later waves made intensive attacks on shipping,

installations, harbor facilities, and similar targets. The attack con-

- [44]

- tinued throughout the day. Many

enemy aircraft were caught on the ground, dispersed and revetted, but

only a few in the air. A fighter-bomber from the Bunker Hill dropped a

bomb between two midget submarines moored side by side. Other islands in

the Ryukyus were reconnoitered and attacked, including Kume, Miyako,

Amami-O, Tokuno, and Minami.

-

- The attack was one of the

heaviest delivered by the Fast Carrier Force in a single day up to that

time. In 1,356 strikes, the planes fired 652 rockets and 21 torpedoes

and dropped 541 tons of bombs. Naha was left in flames; fourfifths of

the city's 533 acres of closely built-up area was laid waste.

Twentythree enemy aircraft were shot down and 88 more destroyed on the

ground or water. Twenty cargo ships, 45 smaller vessels, 4 midget

submarines, a destroyer escort, a submarine tender, a mine sweeper, and

miscellaneous other craft were sunk. "The enemy is brazenly

planning to destroy completely every last ship, cut our supply lines,

and attack us" was the gloomy observation of a Japanese soldier on

the island on that day.2

-

- Admiral Mitscher's estimate of

results was probably conservative. A Japanese Army report on the

attack listed in addition a destroyer and a mine sweeper as sunk.

According to the report, almost 5,000,000 rounds of machinegun

ammunition and 300,000 sacks of unpolished rice were among the supplies

destroyed. The report noted that antiradar "window" had been

used by the Americans, and that propaganda leaflets had been dropped.

Nowhere did the Japanese report mention one of the most significant

accomplishments of the task force during the day-photographic coverage

of important areas throughout the Ryukyus.3

-

- Okinawa was not assaulted again

until 1945, when carrier planes raided the Ryukyu and Sakashima Islands

on 3 and 4 January during a heavy attack on Formosa by the Fast Carrier

Task Force. The primary objective of the task force was the destruction

of enemy air strength on Formosa in preparation for the invasion of

Luzon, and the attack on Okinawa was limited in extent because of the

long distance the fighters had to fly to the target. On 22 January,

Admiral Mitscher's carrier force moved a second time against the Ryukyus,

with the primary mission of photographing the islands. Unfavorable

weather interfered with some of the sorties, but pilots obtained

photographic coverage of 80

- [45]

- percent of priority areas and

attacked ground installations, aircraft, and shipping. The operations

were small compared to those of 10 October but to the enemy they must

have seemed impressive. A Japanese superior private in the infantry

wrote indignantly in his diary on 22 January:

-

- Grumman, Boeing, and North

American Planes came over one after another continuously. Darn it, it

makes me mad! While some fly around overhead and strafe, the big

bastards fly over the airfield and drop bombs. The ferocity of the

bombing is terrific. It really makes me furious. It is past 1500 and the

raid is still on. At 1800 the last two planes brought the raid to a

close. What the hell kind of bastards are they? Bomb from 0600 to 1800!

I have to admit, though, that when they were using tracers this morning,

it was really pretty:4

-

- On 1 March the Fast Carrier Task

Force, now operating as Task Force 58, a part of Admiral Spruance's

Fifth Fleet, delivered another strike on the Ryukyus at the end of a

3-week battle cruise in Japanese home waters which included an attack on

Tokyo. Sweeping down the long Ryukyu chain, American planes hit Amami,

Minami, Kume, Tokuno, and Okino as well as Okinawa. Cruisers and

destroyers shelled Okino Daito, 450 miles from Kyushu, in the closest

surface attack to the Japanese homeland made by the fleet up to that

time. The carrier planes sank a destroyer, 8 cargo ships, and 45 more

craft of various sizes, destroyed 41 enemy planes, and attacked

airfields and installations, particularly in the Okinawa Group. Enemy

opposition was meager and American losses were small.

-

- During February and March 1945,

aircraft based in the Southwest Pacific and in the Marianas made almost

daily runs over the Ryukyus and adjacent waters. Army and Navy search

planes and patrol bombers hunted the waters for Japanese shipping and

helped to isolate Okinawa by destroying cargo vessels, luggers, and

other craft plying between Okinawa and outlying areas. One or two

bombers flying high over Okinawa became so familiar a sight to the

Japanese that they called it the "regular run" and dispensed

with air raid alarms.5

During March American submarines also tightened

the shipping blockade around the Ryukyus.

-

- On 14 March 1945, Task Force 58

steamed out of Ulithi and headed north. Its objective was the Inland

Sea, bounded by Kyushu, western Honshu, and Shikoku; its mission was to

prepare for the invasion of the Ryukyus by attacking

- [46]

-

- PRELIMINARY BOMBARDMENT of Okinawa and supporting islands

began months in advance of the landings. Naha (above) was a prize target

because of its port installations and was leveled long before the

invasion. Also important were bridges (below) along the island's lines

of supply.

-

-

- [47]

-

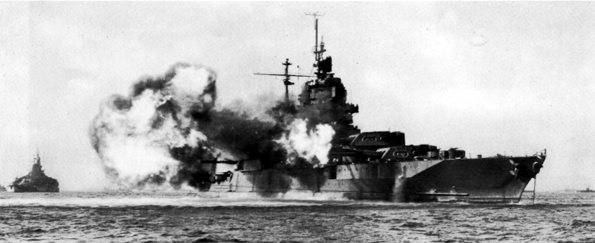

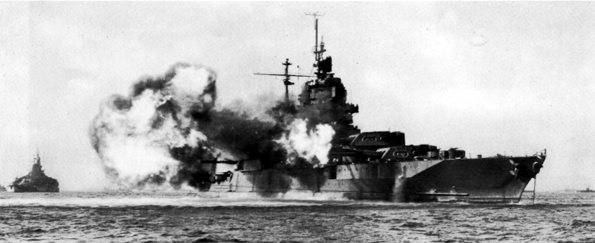

- JAPANESE KAMIKAZE ATTACKS were a constant menace to the

American fleet. Here a Kamikaze plane, falling short of its target,

plunges into the sea after being riddled by antiaircraft fire from an

American cruiser . But the aircraft carrier Franklin (below) was not as

fortunate. Hit off Kyushu by two 550-pound armor-piercing bombs, the

Franklin's fuel, aircraft, and ammunition went up in flame; more than a

thousand of her crew were lost. Gutted and listing badly, the carrier

limped back to New York for repairs.

-

-

- [48]

- airfields and naval bases in the

Japanese homeland. The formidable task force was composed of 10 large

aircraft carriers, 6 smaller carriers, 8 fast battleships, 16 cruisers,

and dozens of destroyers and other vessels; included were famous names

like Hornet, Yorktown, Enterprise, New Jersey, and Missouri.6

-

- As Task Force 58 neared Kyushu

on 17 March, it was spotted by Japanese search planes but was not

attacked. At dawn on the 18th the destroyers formed two radar patrol

groups, one 30 miles north and the other 30 miles west of the main

force, each with carrier-based fighter protection. At 0545, when Task

Force 58 was about 100 miles east of the southern tip of Kyushu, the

first fighters took off from their carriers and headed for Kyushu

airfields. Within an hour more fighters were launched, then the bombers

and torpedo bombers. During the forenoon American planes attacked

aircraft and fields near the coasts of Kyushu. When the enemy air

opposition proved ineffective, the planes were ordered to strike farther

inland, at targets originally scheduled for the next day. The move was

profitable; during the day 102 aircraft were shot down, 275 more on the

ground damaged or destroyed, and hangars, shops, and other airfield

installations heavily bombed.

-

- The Japanese counterattacked

during the day. Their attack was not heavy, but it was carried out in an

aggressive and determined manner. Single enemy aircraft using cloud

cover effectively launched bombing attacks on American carriers. Radars

were not of much help, but visual sightings by destroyers were

invaluable. Although patrol planes shot down twelve of the enemy, and

antiaircraft fire accounted for twenty-one more, the Yorktown and

Enterprise were hit by bombs. Fortunately, damage to the former was

minor, and the bomb that hit the Enterprise failed to explode. Both

could continue flight operations.

-

- The next day, 19 March, Admiral

Mitscher concentrated the attack on the enemy warships at Kobe, Kure,

and Hiroshima in western Honshu, as well as on the airfields in Honshu

and Shikoku. Major Japanese fleet units, including the battleship Yamato, were at Kure and Hiroshima harbors. The attack against the enemy

fleet was only moderately effective, mainly because of extremely heavy

and accurate antiaircraft fire. One group alone lost thirteen planes

over Kure. The Yamato was slightly damaged, an escort carrier severely

damaged, and fourteen other warships damaged in varying degrees.

Merchant ships and coastal vessels were sunk or damaged in the Inland

Sea.7

- [49]

- Soon after the first planes were

launched on 19 March, enemy aircraft appeared over Task Force 58,

concentrating their attack as usual on the carriers. Two 550-lb. bombs

hit the Franklin while she was in the course of launching a strike. She

burned fiercely amid shattering explosions and enveloping clouds of

black smoke, finally becoming dead in the water. A bomb hit the Wasp and

exploded between her second and third decks, but the fire was quickly

put out and the carrier was able to work her aircraft within an hour.

The weather was perfect for the enemy: a thin layer of clouds at 2,500

feet. Antiaircraft gunnery was, however, excellent. Six Japanese planes

attacked one group, coming in at cloud level at an angle of 45 degrees;

all six were blown to pieces.

-

- Task Force 58 retired during the

afternoon of r9 March. Carriers covered the burning Franklin, which was

being towed at five knots, and launched fighter sweeps against Kyushu

airfields in order to disrupt any planned attack on the force as it

withdrew slowly south. Eight enemy planes attacked in the evening but

were intercepted 8o miles away; five were shot down. The total number of

Japanese planes shot out of the air during the day by planes and

antiaircraft fire was 97, and approximately 225 additional enemy

aircraft were destroyed or damaged on the ground. Installations at

more than a score of air bases on Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu were left

in ruins by the operations of the day.

-

- Japanese "bogeys"

shadowed Task Force 58 on 20 March, and enemy planes attacked during the

afternoon and evening. The Enterprise was hit by American gunfire which

started a fire. Eight planes were destroyed and flying operations were

halted. A plane narrowly missed the Hancock and hit and crippled a

destroyer. The Japanese delivered an 8-plane torpedo strike against the

force during the night, without success. On the 21st the enemy launched

a final heavy attack on the retiring ships, with a force of 32 bombers

and 16 fighters. Twentyfour American fighters intercepted the enemy

planes about sixty miles from the force and quickly shot down every

enemy plane, with the loss of only two American fighters. Task Force 58

met its supply ships south of Okinawa on 22 March, and spent a busy day

fueling, provisioning, and taking on replacement pilots and aircraft, in

preparation for the decisive phase of the campaign soon to come. In the

entire course of its foray from 18 to 22 March, Admiral Mitscher's force

had destroyed 528 enemy planes, damaged 16 surface craft, and hit scores

of hangars, factories, warehouses, and dock areas. The success of the

operation was indicated by the subsequent failure of the Japanese to

mount a strong air attack for a week after the American landing on

Okinawa.

- [50]

-

- The first landings in the

Ryukyus were on the Kerama Islands, fifteen miles west of Okinawa. The

boldly conceived plan to invade these islands six days prior to the

landing on Okinawa was designed to secure a seaplane base and a fleet

anchorage supporting the main invasion. An additional purpose was to

provide artillery support for the Okinawa landing by the seizure of

Keise Shima, eleven miles southwest of the Hagushi beaches, on the day

preceding the Okinawa assault. The entire operation was under the

control of the Western Islands Attack Group. The force selected for the

landings in the Keramas was the 77th Division, commanded by Maj. Gen.

Andrew D. Bruce; the 42oth Field Artillery Group was chosen for the

landing on Keise Shima. 8

-

- Steaming from Leyte, where the

77th Division had been engaged in combat since November 1944, the task

force moved toward the objective in two convoys. The as LST's, 14 LSM's,

and 4o LCI's, organized into a tractor flotilla with its own screen,

left on 20 March. Two days later twenty transports and large cargo

vessels followed, screened by two carrier escorts and destroyers. En

route, the training begun on Leyte was continued. Operational plans

were discussed and the men were thoroughly briefed with the aid of maps,

aerial photographs, and terrain models. Booklets on habits, customs,

government, and history of the Okinawans were distributed. After an

uneventful voyage, broken only by false submarine alarms, the entire

task force arrived on 26 March in the vicinity of the Kerama Islands.

-

- Naval and air operations against

the Keramas had begun two days earlier. Under the protection of the

carriers and battleships of Task Force 58, which was standing off east

of Okinawa, mine sweepers began clearing large areas south of the

objective area on 24 March. On 25 March Vice Admiral William H. Blandy's

Amphibious Support Force arrived, and mine sweeping was intensified. By

evening Of 25 March a 7-mile-wide lane had been cleared to Kerama from

the south and a slightly larger one from the southwest. Few mines were

found. Underwater demolition teams came in on the 25th and found the

approaches to the Kerama beaches clear of man-made obstacles, though the

reefs were studded with sharp coral heads, many of which lay only a few

feet beneath the surface at high tide and were flush with the surface at

low tide.9

- [51]

- While the demolition teams

surveyed the approaches, observers from 77th Division assault units

studied their objectives. A fringing reef of irregular width surrounds

each island. The coasts of the islands are generally steep and

irregular. Narrow benches of coral rock lie along the coasts in many

places. The beaches are narrow and are usually bulwarked by 4-foot sea

walls. The only beaches of any considerable length are at the mouths of

steep valleys or within small bays. All but the smallest of the islands

are for the most part masses of steep rocky slopes, covered with brush

and trees and from about 400 to 800 feet in height. Wherever possible

the inhabitants grew sweet potatoes and rice on the terraced slopes of

the hills and in small valley flats near the beaches. There are no roads

and only a few pack-animal trails. No island in the group is suitable

for an airstrip; none can accommodate large masses of troops or

extensive base facilities. The military value of the Keramas lies in two

anchorages, Kerama Kaikyo and Aka Kaikyo, separated from each other by

Amuro Islet, in the center of the group, and bounded on the east by

Tokashiki and on the west by Aka, Geruma, and Hokaji. These anchorages

inclosed 44 berths, from 500 to 1,000 yards long, ranging in depth from

13 to 37 fathoms.10

(See Map No. IV.)

-

- Four battalion landing teams

(BLT's) of the 77th Division made the first landings in the Kerama

Islands on the morning of 26 March. The sky was clear, visibility good,

and the water calm. Escorted by Navy guide boats, waves of amphibian

tractors moved from LST's to four central islands of the groupAka,

Geruma, Hokaji, and Zamami. Cruisers, destroyers, and smaller naval

craft swept the beaches with 5-inch shells, rockets, and mortar shells.

Carrier planes strafed suspected areas and guarded against interference

by enemy submarines and aircraft. Amphibian tanks led the amtracks to

the beaches.11

-

- The first unit ashore was the 3d

BLT of the 305th Regimental Combat Team (RCT). At 0804 12

the 3d BLT

hit the soutfiern beaches of Aka, an island of irregular shape,

measuring 3,400 by 3,000 yards at its extreme dimensions and rising in a

series of ridges to two peaks, one 539 feet and the other 635 feet high.

Aka, "Happy Corner Island," lies near the center of the group.

The 200 boat operators and Korean laborers on Aka put sporadic mortar

and machine-gun fire on the Americans, without inflicting damage, and

then re-

- [52]

-

- TERRAIN IN THE KERAMA RETTO was rugged. In particular the coastal

terrain was precipitous, appearing formidable to the 2d BLT, 306

Infantry, 77th Division, as it approached Hokaji Island on 26 March.

Below is an aerial view of Tokashiki Island.

-

-

- [53]

- treated into the steep central

area as the invaders rapidly overran the beaches and the town of Aka.

-

- The next island invaded-and the

first to be secured-was Geruma, a circular island five-eighths of a mile

in diameter, lying south of Aka. The 1st Battalion Landing Team of the

306th Regimental Combat Team landed on the narrow beach at 0825, meeting

no opposition except for long-range sniper fire. Within three hours it

wiped out a score of defenders and secured the island. Before the

engagement was over, DUKW's began unloading 105-mm. howitzers of the

304th and 305th Field Artillery Battalions for use in operations

scheduled for the next day.

-

- The easiest conquest of the day

was that of Hokaji, an island one mile by Boo yards, lying a few hundred

yards south of Geruma and linked to it by an encircling reef that

follows the contours of the two land masses. The 2d BLT of the 306th

landed on Hokaji at 0921 and secured it without resistance.

-

- At 0900 on 26 March the 1st BLT

of the 305th invaded Zamami, initially meeting little resistance. A

two-legged, humpbacked island, approximately 5,500 yards long east-west

and 400 yards at its narrowest point, Zamami is formed, except for a few

low flat areas along the southern coast, by a group of wooded hills

which rise about 450 feet. Amtracks carried the troops ashore in a deep

bay that cuts into the southern coast. A sea wall fifteen feet from the

water's edge held up the amtracks and forced the men to continue by

foot. The assault elements received sporadic mortar and sniper fire

until they reached the town of Zamami, just to the rear of the beach.

Then a group of Japanese estimated to be of company strength, together

with about 3oo Korean laborers, fled north from the town to the hills.

-

- It became apparent to General

Bruce by late morning of 26 March that the rapid progress of the landing

teams would permit the seizure on the first day of an additional island.

Accordingly the 2d BLT of the 307th, a reserve unit, was directed to

seize Yakabi, northwesternmost islet of the Keramas, which was nearly

oval in shape and a little more than a mile long. At IM 1 the battalion

landed on Yakabi and, meeting only slight opposition, quickly overran

it.13

-

- On both Aka and Zamami the

invading forces met stiffer resistance as they pressed up the steep

slopes into the interior of the islands. On Aka a group of Japanese of

platoon strength was routed by naval gunfire. During the afternoon the

troops killed fifty-eight Japanese in a series of brief skirmishes

- [54]

- on the eastern heights of the

island. Though the enemy fought from caves and pillboxes with small

arms, he had no effective defense. By 1700 of 26 March two-thirds of Aka

was secured; 300 Japanese troops and 400 civilians were still at large

on the island.

-

- On Zamami advance elements of

the 1st BLT of the 305th pushed up into the high ground during the

afternoon without closing with the enemy. From midnight until dawn of

the next day, however, groups of Japanese armed with rifles, pistols,

and sabers tried to break into the American perimeters near the beach.

Company C bore the brunt of the attack, repulsing nine local thrusts

supported by automatic weapons and mortars. One American machine gun

changed hands several times. In a series of night fire fights that at

times developed into savage hand-to-hand combat, the 1st Battalion

killed more than zoo of the enemy at a cost of 7 Americans killed and 12

wounded.14

-

- On 27 March the Americans took

without opposition Amuro, an islet between the two anchorages and Kuba,

the southwesternmost of the Keramas. Fitful action was still in process

on Aka and Zamami on the morning of 27 March. On Aka the 3d BLT of the

305th isolated seventy-five Japanese who were dug in on a ridge and its

reverse slope and were fully supported by mortars and automatic weapons.

After a period of aerial strafing, bombing, rocketing, and mortar fire,

the Americans drove the enemy from their position into the brush. On

Zamami patrols of company size reconnoitered the island and eliminated

scattered groups of the enemy. One organized position was located but

could not be assaulted until the following day, when amtracks blasted

frontally the caves where the last Japanese to be found were dug in.

-

- After a preparation by artillery

firing from Geruma, the 1st BLT of the 306th landed on the west coast of

Tokashiki at 0911 of 27 March, and a few minutes later the 2d BLT landed

to the south of the 1st. Tokashiki was the largest island in the group,

six miles long from north to south and averaging about one mile in

width. Closest of the islands to Okinawa, it formed the eastern barrier

of the Kerama anchorages. Its coasts rise for the most part as cliffs or

steep slopes cut by narrow ravines, the hill masses reaching heights of

more than 650 feet in the center of the island and at the northern and

- [55]

- southern ends. At the backs of

two sheltered bays near the center of the west coast there are two

settlements, Tokashiki and Aware; the sandy beaches near these bays were

selected by the invaders for the landings.

-

- Operations on Tokashiki followed

the pattern of those on the other major islands of the Keramas.

Resistance at first was negligible, the Americans being hindered more by

the rugged terrain than by the scattered sniper fire. The two battalions

abreast drove north over narrow trails. The 3d BLT of the 3o6th,

initially in reserve, was landed with the mission of clearing the

southern portion of the island. By nightfall the 1st and 2d Battalions

were set for the next day's attack on the town of Tokashiki on the east

coast; 3d Battalion patrols had reached the southern tip of the island.

-

- On the following day, 28 March,

the two battalions of the 306th renewed their drive to the north. After

a 500-round artillery preparation the troops occupied Tokashiki, which

had previously been leveled by air and surface bombardment. The area

near the bay was overrun without opposition. The advance continued to

the north, meeting only scattered resistance. On 29 March, after the

three battalions had sent patrols throughout the island, Tokashiki was

declared secured.

-

- By the evening of 29 March all

islands in the Kerama Retto were in American hands. In all, combat

elements of the 77th had made fifteen separate landings, involving five

ship-to-shore movements by LVT's, two ship-to-shore movements by DUKW's,

three ship-to-shore movements by LCVP's with subsequent transfer to

LVT's, and five shore-to-shore movements by LVT's. Despite the

complexity of the maneuvers, the veterans of Guam and Leyte operated

with little confusion. Casualties were low. From 26 to 31 March the 77th

killed 530 of the enemy and took12Iprisoners, at a cost of 3I Americans

killed and 81 wounded.15

-

- The operations on Aka and

Tokashiki had interesting consequences. Although 77th Division patrols

scoured the islands, hundreds of Japanese soldiers and civilians managed

to evade discovery in caves, ravines, and brush throughout the hilly

central parts of the islands. After the Okinawa operation,

representatives from Tenth Army tried unsuccessfully to induce the

Japanese commander on Aka to surrender. The Japanese soldiers and

sailors were not as stubborn, and most of them escaped from the island

and surrendered. On Tokashiki teams of Nisei and Japanese officer

prisoners negotiated with the Japanese commander, who refused to

surrender his garrison of 300 officers and men. He offered, how-

- [56]

- ever, to allow Americans to swim

on Tokashiki beaches provided they kept away from the Japanese camp in

the hills. Only after many months, when he was given a copy of the

Imperial rescript announcing the end of hostilities, did the Japanese

commander surrender, claiming that he could have held out for ten more

years.16

-

- The capture of the Kerama

Islands was followed by the landings on Keise Shima. Lying about eleven

miles southwest of the Hagushi beaches and about eight miles west of

Naha, the group of four tiny coral islets that make up Keise had an

importance in the attack on Okinawa far out of proportion to its size

and topography. From Keise 155-mm. guns could command most of southern

Okinawa. Employing tactics used with great success on Kwajalein, Tenth

Army ordered XXIV Corps artillery to emplace two battalions of 155-mm.

guns on Keise to support the attack.

-

- On 26 March the Fleet Marine

Force Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion, attached to the 77th

Division, scouted Keise without encountering enemy troops or civilians.

On the morning of 31 March a convoy of LST's and LSM's bearing the 420th

Field Artillery Group and attachments arrived off the islets. Over

floating caisson docks set up by Seabees the heavy guns and other

equipment were unloaded. Twenty-four 155-mm. guns were emplaced on the

low, sandy islets, and a cub strip and a bivouac area were established.

By dawn of L Day the batteries were ready to execute their mission of

firing counterbattery, interdiction, and harassing fires deep into enemy

territory.

-

- The guns were set up in full

view of the Japanese occupying high ground on Okinawa. General Ushijima

ordered a "surprise shelling" of Keise to begin at midnight of

31 March, after which army and navy commands were to dispatch

"raiding infiltration units" to Keise, "thereby wiping

out the enemy advanced strong point in one blow." 17

For an hour

after midnight, Japanese 250-mm. shells exploded on the islets. There

were no casualties or damage. The infiltration party never appeared.

This attempt to destroy the artillery on Keise was only the first of

several, the enemy being keenly aware of the threat offered by the

artillery in this flanking position. 18

-

- The assault on Kerama and Keise

had come as a surprise to the Japanese commanders on Okinawa Gunto. The

enemy commanders on Okinawa had

- [57]

- expected that the Americans

would land first on the Hagushi beaches and that their ships would

deploy just east of the Kerama Islands.19

-

- Since the enemy considered the

Keramas as bases for special attack units rather than as defensive

positions, there were few prepared defenses on the beaches or inland

when the Americans appeared. At one time 2,335 Japanese troops occupied

the islands, engaged in installing and operating facilities for the Sea

Raiding units. When, in late 1944 and early 1945, the need for combat

troops on Okinawa became acute, most of these troops were moved to the

larger island. There remained on the Kerama group only about 300 boat

operators of the Sea Raiding Squadrons, approximately Goo Korean

laborers, ana about 100 base troops. The garrison was well supplied not

only with the suicide boats and depth charges but also with machine

guns, mortars, light arms, and ammunition.20

-

- In Kerama Retto, "Island

Chain between Happiness and Good," the Japanese tradition of

self-destruction emerged horribly in the last acts of soldiers and

civilians trapped in the hills. Camping for the night of 28 March a mile

from the north tip of Tokashiki, troops of the 306th heard explosions

and screams of pain in the distance. In the morning they found a small

valley littered with more than i5o dead and dying Japanese, most of them

civilians. Fathers had systematically throttled each member of their

families and then disemboweled themselves with knives or hand grenades.

Under one blanket lay a father, two small children, a grandfather, and a

grandmother, all strangled by cloth ropes. Soldiers and medics did what

they could. The natives, who had been told that the invading

"barbarians" would kill and rape, watched with amazement as

the Americans provided food and medical care; an old man who had killed

his daughter wept in bitter remorse.21

-

- Only a minority of the Japanese,

however, were suicides. Most civilians straggled into American

positions, worn and dirty. In all, the 77th took 1,195 civilian and 121

military prisoners. One group of 26 Koreans gave up on Zamami under a

white flag. On Aka one Japanese lieutenant surrendered voluntarily

because, he said, it would be "meaningless" for him to

commit suicide.22

A Japanese

- [58]

-

- LANDINGS IN THE KERAMAS, made by the 77th Division, met little

opposition. Zamani Island (above) was taken by the 1st BLT, 305th

Infantry, some soldiers of which are shown just before the started

inland. Amtracks were unable to negotiate the seawall and were left at

the beach. Below is a scene on a beach at Tokashiki, captured by

the 1st BLT, 306th, on 27 March. Soldier (right) seems puzzled by the

absence of opposition.

-

-

- [59]

- major captured by a patrol on

Zamami late in May assisted in efforts to induce Japanese remaining in

the islands to surrender.

-

- More than 350 suicide boats were

captured and destroyed by the 77th in the Kerama Islands. They were well

dispersed throughout the islands, many of them in camouflaged hideouts.

These plywood boats were 18 feet long and 5 feet wide. Powered by

6-cylinder Chevrolet automobile engines of about 85 horsepower, they

were capable of making up to 20 knots. Two depth charges weighing 264

pounds each were carried on a rack behind the pilot and were rolled off

the stern of the boat when released. According to captured instructions,

three boats would attack a ship simultaneously, each seeking a vital

spot to release its charge. Strictly speaking, manning the boats was not

suicidal in the same sense as piloting the Kamikaze planes or the

"Baka" bombs. Delay time for the depth-charge igniters was

five seconds. According to a Japanese officer, it was considered

possible to drop the depth charges against a ship and escape, but the

fragility of the boats made survival highly unlikely. As a result, the

pilots were promoted two grades upon assignment and received

preferential treatment. After completion of their missions they were

to receive promotion to second lieutenant; obviously, most such

promotions would be posthumous.

-

- From hideouts in the small

islands, the "Q-boats" with their charges were to speed to the

American anchorages. "The objective of the attack," General

Ushijima ordered, "will be transports, loaded with essential

supplies and material and personnel . . . . The attack will be carried

out by concentrating maximum strength immediately upon the enemy's

landing." 23

The Japanese had carefully mapped out possible

assembly areas of American transports and had prepared appropriate

routes of approach to each area, especially those around Keise.24

The initial thrust into the Keramas completely frustrated the enemy's

plan. In the opinion of General Bruce, the destruction of the suicide

boat base alone was well worth the cost of reducing the Kerama

Islands.25

-

- In a campaign that found the

Japanese prepared for the major moves of the invading forces, the

initial seizure of their "Western Islands" not only caught

them off guard but frustrated their plan of "blasting to

pieces" the American transports with a "whirlwind" attack

by suicide boats.26

The Americans gained

- [60]

-

- "SUICIDE BOATS" wrecked by their crews were found by

the 77th Division as it mopped up in the Keramas. They looked like small

speedboats but were poorly constructed and quite slow, These two craft

(below) were captured in their cave shelters by American troops on

Okinawa. Note booby trap warnings and crude depth charge racks at stern.

-

-

- [61]

-

- SOFTENING UP THE TARGET was the task of the allied

fleet. It stood off Okinawa to place accurate fire on known Japanese installations

and to support underwater demolitions teams clearing the beaches. At the

same time the fleet's air arm conducted aerial bombardment. This low-level

bombing attack on L minus (below) hit enemy shipping in the mouth of the

Bishi River.

-

-

- [62]

- even more than the Japanese

lost. In American hands, this sheltered anchorage became a miniature

naval base from which seaplanes operated and surface ships were

refueled, remunitioned, and repaired.

-

-

- While operations were proceeding

in the Kerama Islands, Task Force 52, under the command of Admiral

Blandy, supervised the specialized tasks that were an essential prelude

to the invasion of Okinawa itself-the mine sweeping, underwater

demolition work, and heavy, sustained bombardment of the target by ships

and aircraft. Task Force 58 stood off to the north and east of Okinawa,

ready to intercept any Japanese surface force approaching from the east,

while Task Force 52 guarded against enemy attack from the west and

against any "express runs" from the north either to reinforce

or to evacuate Okinawa. During the day the ships bombarding Okinawa

stayed close enough together to be able to concentrate for surface

action without undue delay. At night 80 percent of Task Force 52

deployed to the northwest of Okinawa and 20 percent to the northeast.

The northwest group was considered strong enough to cope with any

surface force which the Japanese could bring against it; the northeast

element was to deal with "express runs," and could count on

the support of Task Force 58 if the enemy dispatched a larger, slower,

and more easily detected force to the area east of Okinawa. In case of

emergency, one force could join the other by passing through the unswept

waters north of Okinawa.27

-

- Bombardment of Okinawa began on

25 March when ships of the Amphibious Support Force shelled the

southeast coast. The fire was executed only at long range, however, for

mine-sweeping operations which had commenced the previous day were still

proceeding well offshore. During the following days, as the mine

sweepers cleared areas progressively nearer the coast of Okinawa, the

bombardment ships were able to close in for heavier and more accurate

fire. The Japanese had planted a mine field of considerable strength

along the approaches to the Hagushi beaches, and until mine-sweeping

operations were completed the American ships could not bring the

beaches within range. Not until the evening of 29 March were the

approaches to Hagushi and other extensive areas cleared in what Admiral

Blandy called "probably the largest assault sweep operation ever

executed." Operating under inter-

- [63]

- mittent air attack, American

mine sweepers cleared about 3,000 square miles in 75 sweeps.

-

- From 26 to 28 March the naval

bombardment of Okinawa was at long range; targets were located with

difficulty because of the range and occasional poor visibility, and few

were reported destroyed. Effective bombardment of the island did not

begin until 29 March when battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and

gunboats closed the range and hit their objectives with increasing

effectiveness. Then for the first time the large concentration of

targets in the NahaOroku Peninsula area was taken under effective

fire. On the 30th heavy shells breached the sea walls along the coast

line in many places. Ten battleships and eleven cruisers were now

participating in the attack. On 31 March four heavy ships, accompanied

by destroyers and gunboats, supported the final underwater demolition

operation off the Hagushi beaches. This was completed before noon. Then

the ships concentrated on sea walls and on defensive installations

behind the beaches. Even at the shortest range, however, it was

difficult to locate important targets, and ships had to explore with

gunfire for emplacements and similar structures.

-

- During the seven days before L

Day, naval guns fired more than 13,000 large-caliber shells (6-inch to

r6-inch) in shore bombardment. Including several thousand 5-inch

shells, a total of 5,162 tons of ammunition was expended on ground

targets. All known coast defense guns in the area were destroyed or

severely damaged. The enemy had established a few heavy pillbox-type

installations and numerous emplacements along the beaches and farther

inland, but most of them were empty. Naval guns fired extensively into

cliffs and rocky points overlooking and flanking the beaches to disclose

defensive positions such as the enemy had frequently used in the past;

few, however, were found.28

By the afternoon of 31 March, Admiral

Blandy could report that "the preparation was sufficient" with

the exception of certain potentially dangerous installations still in

the Naha area. Enemy shore batteries did not open up on ships during the

preliminary bombardment.29

-

- Aircraft from Task Force 58 and

from the escort carriers flew 3,095 sorties in the Okinawa area prior to

L Day. Their primary objective was enemy aircraft based on the

islands. Second priority was given to small boats and "amphibian

tanks," which later were discovered to be suicide attack boats

- [64]

- fitted with depth charges. After

these, they gave preference to installations such as coastal defense

guns, field artillery, antiaircraft guns, floating mines, communications

facilities, and barracks areas.

-

- Planes from Task Force 58

concentrated on targets that could not be reached by naval gunfire.

Escort carrier aircraft protected the mine sweepers and underwater

demolition teams, conducted preliminary attacks against Kerama and Keise,

and supported the assault generally. The preliminary air assault got

under way on 25 March with bombing, napalm, and rocket attacks on

Tokashiki Island in the Keramas and attacks on air installations on

Okinawa. On the 26th, 424 sorties were made against suicide boat and

midget submarine bases, airfields, and gun positions. On the following

day attacks continued on these targets, and barracks areas were also

worked over with bombs, napalm, and rockets.

-

- From 28 to 31 March air missions

were closely coordinated with projected ground operations as the escort

carriers executed missions requested by Tenth Army. Aircraft

concentrated on gun positions at scattered points throughout southern

Okinawa. They bombed a bridge along the northern shore of Nakagusuku

Bay and broke it in ten places. They scored fifteen direct hits with

napalm on installations near the Bishi River. Operations against enemy

air and naval bases continued. On 29 March carrier planes destroyed 27

enemy planes on Okinawa airfields and probably destroyed or damaged 24

more; planes hit on the ground during the period totaled 80. Barges,

wooden boats, and other small enemy craft were systematically gutted. At

least eight submarine pens were demolished at Unten Ko on the north

coast of Motobu Peninsula.30

-

- Under cover of carrier planes

and naval gunfire, underwater demolition teams performed reconnaissance

and necessary demolitions on Keise, on the demonstration beaches of

southeastern Okinawa, and on the Hagushi landing beaches. Planes made

strafing, bombing, and rocket runs on the beaches, and smoker planes,

where needed, concealed the teams with smoke. Three lines of ships,

increasing in fire power from the beach out, gave the underwater

demolition teams formidable support. LCI(G)'s (Landing Craft,

Infantry, Fire Support) armed with 40-mm. guns stood approximately

1,200 yards off the beach; then a line of destroyers at about 2,700

yards covered the shore to 300 yards inland with 40-mm. and 5-inch

gunfire; and 1,000 yards behind the destroyers were battleships and

cruisers ready with secondary and antiaircraft batteries to neutralize

all ground from 300 to 2,000 yards inland.

- [65]

- Underwater demolition teams

first reconnoitered the Hagushi beaches on 29 March, after a delay of a

day because of the large number of mines found in the areas off the

beaches. Three battleships, 3 cruisers, 6 destroyers, and 9 LCI(G)'s

supported the operation. The machine-gun and mortar fire encountered

was silenced by the fire support units. The swimmers found approximately

2,900 wooden posts, from 6 to 8 inches in diameter and from 4 to 8 feet

high, most of them off beaches north of the Bishi River. In some places

there were four rows of these posts. On 30 and 31 March underwater

demolition teams destroyed all but 200 of the posts, using tetratol tied

in with primacord. A demolition operation was carried out on the

demonstration beaches under gunfire coverage; several tons of tetratol

were detonated on the edge of the reef even though no obstacles had been

found.31

-

- As the Americans closed in on

Okinawa from 26 to 31 March, the enemy suddenly found itself confronting

another adversary-the Royal Navy. A British carrier force, under the

command of Vice Admiral H. B. Rawlings and assigned to the Fifth Fleet,

struck at the Sakishima Islands on 26, 27, and 31 March. Its planes made

345 sorties over Sakishima, dropped more than 81 tons of bombs, and

fired more than 200 rockets. The British labored under several

handicaps. They lacked night fighters, and their ships carried a much

smaller number of planes than did the large American carriers. Also,

their supply resources afloat were rudimentary. Nevertheless, the

British rendered valuable assistance to the assault forces by

considerably reducing the magnitude and number of enemy air attacks

staged from Sakishima airfields.32

-

- Task Force 58 remained in a

constant state of readiness, and on 28 March it demonstrated its fast

striking power in convincing fashion. Word was received from Admiral

Spruance of a reported sortie of enemy fleet units from the Inland Sea

on a southwesterly course. Immediately a task group headed north at high

speed to attack the enemy ships. The Japanese force, however, was not

found. On the 29th another task group joined in the search, but without

success. The foray was not allowed, however, to be useless. On their way

back to the carriers, planes from both groups bombed airfields in the

Kagoshima Bay area of Kyushu and attacked miscellaneous shipping with

good results.33

- [66]

- Despite American attacks on

enemy airfields and installations, approximately 100 Japanese planes

made 50 raids in the Okinawa area during the period from 26 to 31 March.

Many of the attacking planes tried to suicidecrash the American

ships-an omen of the basic Japanese tactics in the tremendous sea-air

war soon to come. With few exceptions, the attacks came during early

morning or by moonlight. Already the Japanese were using a considerable

assortment of new- and old-type planes. As they approached, the enemy

raiders generally split up into single planes or a-plane groups, which

made individual, uncoordinated attacks. There was some evidence that

planes flew in from outlying bases and landed on fields in Okinawa at

night. Favorite targets of the Japanese were pickets and patrols,

including small craft, but several planes attacked formations of heavy

ships. Of the enemy planes that suicide-crashed, nine hit their targets

and ten made near misses. Much of the damage from these attacks was

superficial, but several ships suffered serious damage and casualties.

Ten American ships, including the battleship Nevada and the cruisers

Biloxi and Indianapolis, were damaged in the period from 26 to

31 March,

eight of them by suicide planes; two other vessels were destroyed by

mines. The defending ships and planes shot down approximately forty-two

of the attackers.34 In addition to the suicide attacks the Japanese

conducted a few bombing, strafing, and torpedo attacks during the

period, but these were without significant results.

-

- On the afternoon of 31 March

naval auxiliary vessels delivered the latest aerial photographs of the

beaches to the transports approaching the target area. As night fell,

the vast armada of transports, cargo ships, landing craft, and war ships

ploughed the last miles of their long voyage. Before dawn they would

rendezvous off the Hagushi beaches in the East China Sea. Weather for 1 April promised to be excellent.

[67]

page created 10 December 2001

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents