Chapter III:

Winning The Okinawa Beachhead

Dawn of Easter Sunday, 1 April

1945, disclosed an American fleet of 1,300 ships in the waters adjacent

to Okinawa, poised for invasion. Most of them stood to the west in the

East China Sea. The day was bright and cool-a little under 75°; a

moderate east-northeast breeze rippled the calm sea; there was no surf

on the Hagushi beaches. Visibility was 10 miles until 0600, when it

lowered to from 5 to 7 miles in the smoke and haze. More favorable

conditions for the assault could hardly be imagined.

The Japanese doubtless marveled

at the immensity of the assemblage of ships, but they could not have

been surprised at the invasion itself. The Kerama Islands had been

seized; Okinawa had been heavily bombarded for days; and underwater

demolition teams had reconnoitered both the Hagushi beaches and the

beaches above Minatoga on the southeast coast, indicating that landings

were to be expected at either place or both. Moreover, Japanese air and

submarine reconnaissance had also spotted the convoys en route.1

The Japanese had been powerless

to interfere with the approach to the Ryukyus. Bad weather, however, had

caused not only seasickness among the troops but also concern over the

possibility that a storm might delay the landings. It was necessary for

some convoys to alter their courses to avoid a threatening typhoon. The

rough seas caused delays and minor damage and resulted in other

deflections from planned courses. Thus on the evening before L Day

various task forces converging on Okinawa were uncertain of their own

positions and those of other forces. All arrived on time, however, and

without mishap.2

For the men, observing the

outline of the strange island in the first rays of light before the

beaches became shrouded in the smoke and dust of naval and air

bombardment, this Easter Sunday was a day of crisis. From scale models

[68]

of Okinawa studied on shipboard

they had seen that the rising ground behind the landing beaches, and

even more the island's hills and escarpments, were well suited for

defense. They had read of the native houses, each protected by a high

wall, and of the thousands of strange Okinawan tombs which might serve

the enemy as pillboxes and dugouts. They had been encouraged by the

weakness of Kerama Retto's defenses, but the generally held expectations

of an all-out defense of the beaches on the first Japanese

"home" island to be invaded was one to appall even the dullest

imagination. And behind the beaches the men were prepared to meet deadly

snakes, awesome diseases, and a presumably hostile civilian population.3

H Hour had been set for 0830. At

0406 Admiral Turner, Commander of Task Force 51, signaled, "Land

the Landing Force." 4

At 0530, twenty minutes before dawn, the fire

support force of 10 battleships, 9 cruisers, 23 destroyers, and 177

gunboats began the pre-H-Hour bombardment of the beaches. They fired

44,825 rounds of 5-inch or larger shells, 33,000 rockets, and 22,500

mortar shells. This was the heaviest concentration of naval gunfire ever

to support a landing of troops. About seventy miles east of Okinawa,

Task Force 58 was deployed to furnish air support and to intercept

attacks from Kyushu. In addition, support carriers had arrived with

troop convoys. At 0745 carrier planes struck the beaches and near-by

trenches with napalm.5

Meanwhile LST's and LSM's, which

had carried to the target both the men composing the first assault

forces and the amphibian vehicles in which they were to ride, spread

their yawning jaws and launched their small craft, loaded and ready for

the shore. Amphibian tanks formed the first wave at the line of

departure, 4,000 yards from the beach. Flagged on their way at 0800,

they proceeded toward land at four knots. From five to seven waves of

assault troops in amphibian tractors followed the tanks at short

intervals.6

[69]

Opposite each landing beach,

control craft, with pennants flying from the mast, formed the assault

waves of amphibious vehicles in rotating circles. At 0815 the leading

waves of amtracks uncoiled and formed a line near their mother control

craft. Five minutes later the pennants were hauled down and an almost

unbroken 8-mile line of landing craft moved toward the beaches.

Gunboats led the way in, firing

rockets, mortars, and 40-mm. guns into prearranged target squares, on

such a scale that all the landing area for 1,000 yards inland was

blanketed with enough 5-inch shells, 4.5-inch rockets, and 4.2-inch

mortars to average 25 rounds in each 100-yard square. Artillery fire

from Keise added its weight. After approaching the reef, the gunboats

turned aside and the amphibian tanks and tractors passed through them

and proceeded unescorted, the tanks firing their 75-mm. howitzers at

targets of opportunity directly ahead of them until landing.

Simultaneously, two 64-plane groups of carrier planes saturated the

landing beaches and the areas immediately behind with machine-gun fire

while the fire from supporting ships shifted inland. When the assault

wave moved in, the landing area had been under constant bombardment for

three hours.7

As the small boats made their

way steadily toward the shore the men kept expecting fire from the

Japanese. But there was no sign of the enemy other than the dropping of

an occasional mortar or artillery shell, and the long line of invasion

craft advanced as though on a large-scale maneuver. The offshore

obstacles had either been removed by the underwater demolition teams or

were easily pushed over by the amphibian tractors. Some concern had been

felt as to whether, despite the rising tide, the Navy landing boats

would be able to cross the coral reef, and the first waves were to

inspect the reef and send back information. The reef did not hinder the

first waves, in amphibian vehicles, but those who followed in boats had

difficulty and were therefore ordered to transfer at the edge of the

reef and cross in LVT's.

Beginning at 0830, the first

waves began to touch down on their assigned beaches. None was more than

a few minutes late. The volume of supporting fire had increased until a

minute or two before the first wave landed; then suddenly the heavy fire

on the beach area ended and nothing was to be heard except the rumble of

the shells that were shifted inland. Quickly the smoke and dust that had

shrouded the landing area lifted, and it became possible for the troops

to see the nature of the country directly before them. They

[70]

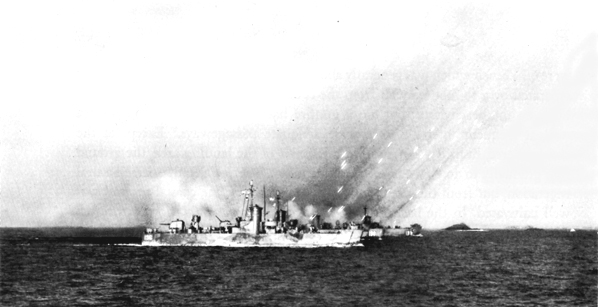

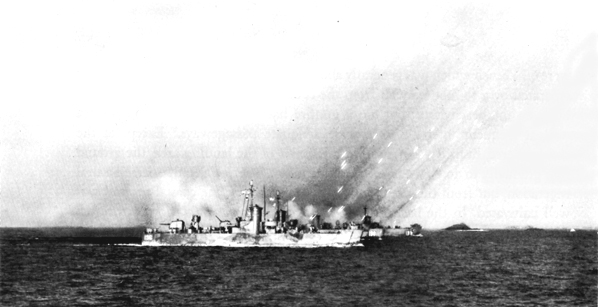

BOMBARDING THE BEACHES directly preceded the landings. It was

carrieed on at closest range by rocket gunboats of the U.S. Fleet. These

boats led the way to the Hagushi beaches, turned aside to proceed ashore

unescorted. Meanwhile the Tennessee and other American

battleships kept up a steady support barrage

[71]

were on a beach which was

generally about twenty yards in depth and which was separated by a 10-foot

sea wall from the country beyond. There were few shell holes on the

beach itself, but naval gunfire had blown large holes in the sea wall at

frequent intervals to provide adequate passageways 8

Except at the cliff-bordered Bishi River mouth, in the center of the landing area, the

ground rose gradually to an elevation of about fifty feet. There was

only sparse natural vegetation, but from the sea wall to the top of the

rise the coastal ground was well cultivated. In the background, along

the horizon, hills showed through the screen of artillery smoke. Farther

inland, in many places, towns and villages could be seen burning and the

smoke rising above them in slender and twisted spires. These evidences

of devastation, however, made less impression upon the men than did the

generally peaceful and idyllic nature of the country, enhanced by the

pleasant warmth, the unexpected quiet, and the absence of any sign of

human life.

New waves of troops kept moving

in. Before an hour had passed III Amphibious Corps had landed the

assault elements of the 6th and 1st Marine Divisions abreast north of

the Bishi River, and XXIV Corps had put ashore those of the 7th and 96th

Infantry Divisions abreast south of that river. The 6th Marine Division

and the 96th Division were on the flanks. Two battalion landing teams

from each of two assault regimental combat teams in the four divisions,

or more than 16,000 troops, came ashore in the first hour.9

(See Map No.

V.)

The assault troops were followed

by a wave of tanks. Some were equipped with flotation devices, others

were carried by LCM(6)'s which had themselves been transported by LSD's,

and still others were landed by LSM's. After debarking the assault

waves, the amphibian tractors returned to the transfer line to ferry

support troops, equipment, and supplies across the reef onto the beach.

LVT, DUKW, and small-boat control points were established at the

transfer line. Amphibian vehicles preloaded with ammunition and supplies

proceeded inland as needed. 10

The entire landing on Okinawa

had taken place with almost incredible ease. There had been little

molestation from enemy artillery, and on the beaches

[72]

THE LANDINGS were made in amphibian craft which were shepherded to

shore by control craft (arrows). heavy support fire which had blanketed

the beaches with smoke and dust lifted seconds before the first troops

touched down. Absence of enemy opposition to the landings made the

assault seem like a large-scale maneuver as troops (below) left their

craft and quickly consolidated. Other waves followed closely.

[73]

no enemy and few land mines had

been encountered. The operation had taken place generally according to

plan; there was little disorganization and all but a few of the units

landed at the beaches assigned to them. The absence of any but the most

trivial opposition, so contrary to expectation, struck the men as

ominous and led them to reconnoiter suspiciously. After making certain

that they were not walking into a trap, the troops began moving inland,

according to plan, a very short time after they had landed.

Spirits rose as the marines and

soldiers easily pushed up the hillsides behind the beaches. The land was

dry and green with conifers and the air bracing-a welcome change from

the steaming marshes and palm trees of the islands to the south. An

infantryman of the 7th Division, standing atop a hill just south of the

Bishi River soon after the landing, expressed the common feeling when he

said, "I've already lived longer than 1 thought 1 would." 11

Simultaneously with the landing

Maj. Gen. Thomas E. Watson's ad Marine Division feinted a landing on

Okinawa's southeast coast, above Minatoga, with the hope of pinning down

the enemy's reserves in that area. This diversion simulated an actual

assault in every respect. The first part of the demonstration group left

Saipan on 25 March, and the main body arrived at Okinawa early in the

morning of L Day. The Japanese attacked the force with their suicide

planes, and one transport and an LST were damaged. Under cover of a

smoke screen, seven boat waves, each composed of twenty-four LCVP's,

carried ad Marine Division troops toward the beach. As the fourth wave

crossed the line of departure at 0830-H Hour for the main assault on the

Hagushi beaches-all boats reversed course. By 1500 all the landing

vessels had been recovered by their parent vessels. The only enemy

reaction to the demonstration was one salvo of four rounds. The next day

the demonstration was repeated, and the marines retired from the area.

Proudly the Japanese boasted that "an enemy landing attempt on the

eastern coast of Okinawa on Sunday morning [1 April] was completely

foiled, with heavy losses to the enemy." 12

Having ascended the slight hills

at the landing beaches, the troops moved inland cautiously. Their

immediate objectives were the two airfields, Kadena and Yontan, each

about a mile inland. At 1000 the 27th RCT of the 7th Divi-

[74]

sion had patrols on Kadena

airfield, which was found to be deserted, and at 1030 the front line was

moving across the airstrip. A few minutes later it was 200 yards beyond.

With similar ease the 4th Marines of the 6th Marine Division captured

the more elaborate Yontan airfield by 1130. Wrecked Japanese planes and

quantities of supplies were strewn about on both fields.13

By nightfall the beachhead was

15,000 yards long and in places as much as 5,000 yards deep. More than

60,000 men were ashore, including the reserve regiments of the assault

divisions. All divisional artillery landed early, and, by dark,

direct-support battalions were in position. Numerous tanks were ashore

and operating, as well as miscellaneous antiaircraft artillery units and

15,000 service troops. Kadena airfield was serviceable for emergency

landings by the evening of the first day. The 6th Marine Division halted

for the night on a line running from Irammiya to the division boundary

below Makibaru. The 7th Division had pressed inland nearly three miles,

knocking out a few pillboxes and losing three tanks to mines. On the

southern flank, the 96th Division had established itself at the river

south of Chatan, on the high ground northwest of Futema, in the

outskirts of Momobaru, and in the hills northwest and southwest of Shido.

There were gaps in the lines in many places, but before nightfall they

had been covered by reserve units or by weapons.14

Although in the hills around

Shuri the enemy had superb observation of the Hagushi beaches and of the

great American armada that stood off shore, he had been content for the

time being to leave the burden of opposition to the Japanese air force.

Some delaying actions were fought by small groups of Japanese, and some

rounds of artillery and mortar fire were directed at the landing craft

and the beaches, but the total resistance was negligible.

In the air the enemy did his

best, but did not inflict much damage. Thrown off balance by the strikes

of Task Force 58 against the airfields on Kyushu on 18-19 March,

Japanese air resistance to the landings was aggressively pressed home

but was small in scale. Suicide hits were scored on the battleship West

[75]

Virginia, two transports, and an

LST; another LST was damaged by a suicide plane's near miss, and two

ships were damaged in other ways.15

An indefinite number of Japanese

planes were shot down during the day by ships' fire and defending

fighters.16

Favored by perfect weather and

light resistance, American forces moved swiftly during the next two

days, 2 and 3 April. By 1400 on 2 April the 17th Infantry, 7th Division,

had established itself on the highlands commanding Nakagusuku Bay, on

the east coast, and had extended its patrols to the shore of the bay.

The speed of its advance had left the units on its flanks some distance

behind. To the south the 32d Infantry came abreast late in the afternoon

of 2 April, after reducing a strong point south of Koza with tanks. To

the north, where the 1st Marine Division had encountered rugged terrain

and difficult supply problems, a 6,000-yard gap was taken over by the

184th Infantry. Okinawa was now cut in two, and units of the Japanese

Army in the northern and southern parts of the island were

separated.17

The 96th Division made slow

progress during the morning of 2 April in the country around Shido. Here

it found heavily forested ridges, empty caves and dugouts, and mines and

tank traps along the rough trails. Before evening the 381st Infantry had

pushed through Shimabuku but had been stopped by enemy opposition in and

around Momobaru. After a sharp fight the 383d Infantry took a hill just

south of Momobaru, and with the help of an air strike, artillery, and

tanks it reduced a ridge northeast of Futema. That night its lines

stretched from the west coast just north of Isa to a point southwest of

Futema on the Isa-Futema road and along the northern edge of Futema 18

On 3 April XXIV Corps turned its

drive southward. Leaving the 17th Infantry to guard and consolidate its

rear, the 32d Infantry pushed all three of its battalions southward

along Nakagusuku Bay. After gaining 5,000 yards it occupied Kuba and set

up its lines in front of Hill 165, the coastal extremity of a line of

hills that swept southwest of the village. Fire was received from the

hill, and a few Japanese were killed in a brief fire fight. Ten rounds

of enemy artillery were received in the regiment's sector, a sign of

awakening resistance.19

[76]

Coordinating their advance with

that of the Sad Infantry on their left, elements of the 96th Division

moved toward Hill 165 and Unjo. An unsuccessful attempt was made to take

the hill. Other 96th Division units advanced to positions in the

vicinity of Kishaba and Atanniya and northeast of Nodake. Futema and the

high ground 600 yards south of it were taken. On the west flank the

division's line went through Isa to the southeastern edge of Chiyunna.20

Having completed its wheeling

movement to the right, the 96th Division was ready to drive south in

conjunction with the 7th Division. Civilians and prisoners of war stated

that Japanese troops had withdrawn to the south. XXIV Corps now changed

the boundary line between its two assault divisions. On the next day, 4

April, four regiments were to move into line across the narrow waist of

the island-the Sad and the 184th of the 7th Division on the east, and

the 382d and the 383d of the 96th Division on the west. The real battle

for Okinawa would then begin.21

Meanwhile, in the zone of III

Amphibious Corps, the 1st Marine Division continued on 2 April 1945 to

the line Ishimmi-Kutoku and Chatan. It met a few small pockets of

resistance but was slowed mainly by the primitive roads and rough

terrain. On the following day this division again advanced against

little opposition, its forward elements reaching Nakagusuku (Buckner)

Bay by 1600. At the same time its reconnaissance company explored

Katchin Peninsula and the east coast roads north to Hizaonna. On 4 April

all three regiments of the 1st Marine Division were on the eastern shore

of Okinawa, and the division's zone of action was completely occupied.22

On L plus 1, the 6th Marine

Division continued its advance into the foothills of Yontan-Zan,

patrolled the peninsula northwest of the Hagushi beaches, and captured

the coastal town of Nagahama. In this mountainous sector, well-worn

trails crisscrossed the wooded hills and ridges, and caves pitted the

coral walls and steep defiles. By manning both ridge tops and caves, the

Japanese put up tenacious resistance. The 6th Marine Division killed

about 250 of the enemy in two such strong points on 2 April. Next day it

advanced 7,000 yards, the 22d Marines on the left maintaining supply

through rough wild country by "weasels." One more day's march

would bring this division to the L-plus-15 line drawn from Nakodamari to

Ishikawa.23

[77]

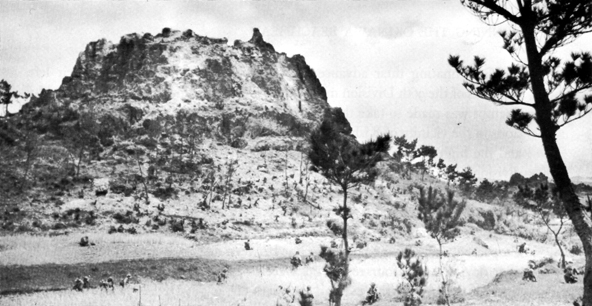

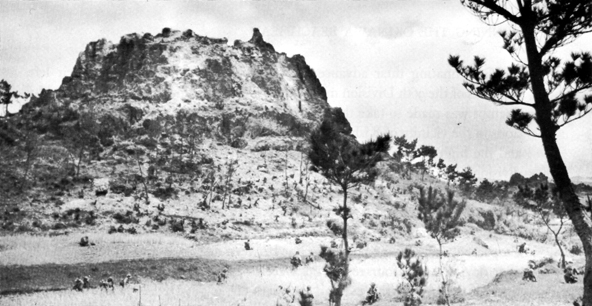

MOVING INLAND, American troops at first met little or no

opposition. South of Kadena airfield, in coral crags deeply scarred by

naval bombardment, 96th Division infantrymen engaged in their first hill

and cave fighting in Okinawa, Other 96 Division troops, in amphibian

tanks (below), turned south on the right flank and paused just north of

Sunabe to reconnoiter; here they raised the American flag.

[78]

The tempo of Japanese air

attacks increased somewhat during the first three or four days after L

Day, and many ships were damaged and some lost during this period.

Vessels not actually engaged in unloading withdrew some distance from

Okinawa each night, but this did not make them proof against attack. The

Henrico, an assault transport carrying troops and the regimental staff

of the 305th Infantry, 77th Division, was crashed by a suicide plane

south of the Keramas at 1900 on 2 April. The plane struck the

commodore's cabin and plunged through two decks, its bomb exploding on

the second deck. The commodore was killed, as were also the commanding

officer, the executive officer, the S-1, and the S-3 of the 305th. The

ship's total casualties were 30 killed, 6 missing, and 50 injured.24

The first waves of the troops

were no sooner across the beaches and moving up the slopes than the

complex machinery of supplying them, planned in intricate detail over

long months, went into action. The problem was to move food, ammunition,

and equipment for more than 200,000 men across beaches with a fringing

reef from 200 to 400 yards wide 25

to dumps in rear areas, and then to

the troops; to widen the native roads; to repair the captured airfields;

and to alleviate the inevitable distress of the civilian population

while rendering it incapable of interference.

While the beaches varied widely

in serviceability, they were in general well adapted to unloading

purposes. LCM's and LCVP's could cross the reef for four or five hours

at each flood tide and unload directly on the beach; during middle and

low tides their cargoes had to be transferred to amphibian vehicles at

transfer barges. LST's, LSM's, and LCT's were beached on the reef at

high tide to enable vehicles and equipment to be discharged during the

next low tide, and the bulk cargo by DUKW's and LVT's at any tide.

Various expedients were used to hasten the unloading. Night unloading

under floodlights began on a April, and the work proceeded without

interruption except when enemy aircraft was in the vicinity. Ponton

causeways accommodating LST's were established at predetermined sites.

By 4 April a T-pier, with a 300-foot single-lane approach and a 30- by

170-foot head, and a U-pier,

[79]

with two 500-foot approaches and

a 60- by 175-foot wharf section, had been set up on the beaches. The

piers were soon supplanted by six single-lane causeways. By the same day

an L-shaped pier, with a 1,400 foot single-lane approach and a 45- by

175-foot head, had been completed. Several sand piers were also

constructed. As the marines rolled northward, additional unloading

points were established as far north as Nago. Ponton barges carried to

Okinawa on cargo ships were assigned varying jobs from day to day. By 11

April, 25 had been equipped with cranes and were operating as transfer

barges, 53 were operating as lighters, and 6 as petroleum barges, while

8 were being used for evacuating casualties. A crane barge was capable

of handling 400 tons in a 20-hour day when enough amphibian vehicles

were available to make the runs ashore. 26

Control of operations on the

beaches, initially in the battalion landing teams, passed step by step

through the echelons of command until Tenth Army, acting through the

Island Command and the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, assumed

responsibility on 9 April. Navy beachmasters maintained liaison with the

ships and scheduled the beaching of landing ships and the assignment of

lighterage. General unloading began on 3 April. It was soon apparent

that the limiting factor was the availability of transport from the

beaches to the dumps. The shortage of service units and equipment due to

space limitations was immediately felt, especially in the Army zone; the

problem was eased for the Marines by the use of 5,000 replacements

landed with the Marine divisions. The rapidity of the advance and the

immediate uncovering of Yontan and Kadena airfields required a

rearrangement of supply priorities. The difficulties in initiating so

intricate an undertaking near the enemy's homeland were prodigious, and

it required time and the process of trial and error to overcome them.

Suicide planes and suicide boats were a constant menace, and on the

afternoon of 4 April the weather came to the aid of the enemy. A storm,

bringing with it from 6- to 10-foot surf on the Hagushi beaches, lasted

through the night and the following day. All unloading ceased, and some

landing craft hit against the reef and were damaged. Again on 10 April

surf backed by a high wind brought work to a standstill, and on 11 April conditions were but slightly improved. Rain accompanying these

storms made quagmires of the roads and further complicated the supply

problems. Despite these handicaps, the assault shipping was 80 percent

unloaded by

[80]

16 April, and 577,000

measurement tons had crossed the Hagushi beaches, a larger amount than

had been anticipated in the plans.27

In addition to beach

installations, base facilities necessary for the immediate success of

the operation had to be developed quickly. Existing roads had to be

improved and new roads built; the two airfields required repairs and

expansion; and facilities for bulk storage of petroleum products,

especially aviation gas, with connections to tankers off shore, were

urgently needed. It was not long before the road down the west coast of

Okinawa blossomed with markers which proclaimed it "US 1," and route numbers were similarly assigned to all main

roads as they were taken, in accordance with the Engineers' plans.

Okinawa's roads were, for the most part, unsurfaced and only one or one

and one-half lanes in width. On L Day beach-exit and shore-party dump

roads were improved; next, the main supply routes to the troops and

roads to permanent and semipermanent supply installations. During the

rains of 4-5 and 10-11 April the spinning wheels of endless lines of

trucks soon tore through the crusts of the more traveled highways and

became mired. In dry weather the surface became pulverized, and the

heavy military traffic raised clouds of dust that sometimes cut

visibility to the length of the hood. Engineers widened and resurfaced

the main thoroughfares, using coral from existing and newly opened pits,

coral sand, rubble from destroyed villages, and limestone. Bridges that

were too narrow or too weak to carry American trucks and tanks were soon

replaced by Bailey bridges, which could be set up and taken down much in

the fashion of an Erector span. It was late in April before equipment

was available for the construction of gasoline tank farms. 28

An area 30 feet by 3,000 feet on

the Yontan runway was cleared and the bomb craters filled on L Day; by

the evening Kadena was also ready for emergency landings.29

Nineteen

artillery spotting planes were flown in from CVE's and LST's on 2 April

and began operations on 3 April.30

The work of conditioning the two

fields began in earnest the following day.31

Land-based fighter

groups arrived at Yontan on 7 April and at Kadena two days later,

improving local control of the air and making more aircraft available

for support. Air

[81]

SUPPLYING AND DEVELOPING THE BEACHHEAD had by L plus 3

made substantial progress. Supply ships were run in to the reef's

edge, where they unloaded into trucks or amphibian vehicles.

Indentation in shore line is Bishi River mouth, with Yontan airfield

on horizon beyond; one runway (below) had been sufficiently repaired

to allow use of land-based figther planes

[82]

evacuation of the wounded to the

Marianas by specially equipped C-54's began on 8 April.32

At the

same time a C-47 equipped for spraying DDT was brought into Yontan to

take over the sanitation mission performed since a April by

carrier-based aircraft.33

The 69th Field Hospital landed on 3 April

and received its first casualties two days later. Until it was

established, the divisions had evacuated their casualties immediately by

LCVP's and DUKW's to one of eight LST(H)'s lying off the Hagushi

beaches. Each hospital ship could take care of 200 patients and perform

emergency surgery. By 16 April Army and Marine hospitals ashore had a

capacity of 1,800 beds.34

Thousands of destitute Okinawans,

dazed by the preinvasion bombardment of their island and the swift

advance of the Americans, entered the custody of the Military Government

authorities almost at once. Initially placed in stockades to keep them

out of the way, they were quickly moved to selected villages which had

escaped destruction. Thus by 5 April 1,500 civilians held in a barbed

wire enclosure just south of Kadena were being moved by truck to

Shimabuku, where they would have freedom of movement within boundaries

established by the military police. Other collection points were

similarly emptied and closed.35

Thus, in an amazingly short time

the beachhead had been won and the supply lines established. By 4 April

Tenth Army held a slice of Okinawa 15 miles long and from 3 to 10 miles

wide. The beachhead included two airfields of great potentialities,

beaches that could take immense tonnage from the cargo ships, and

sufficient space for the dumps and installations that were rapidly being

built. The months of planning and preparation had borne their first

fruit.[83]

page created 10 December 2001

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents