Chapter IV:

Where Is The Enemy

The ease with which American forces

landed and established themselves on Okinawa gave rise to widespread speculation

as to the whereabouts of the Japanese Army. The most optimistic view was that

the enemy had been strategically outguessed and had prepared for the Americans

at some other island, such as Formosa. Or, if Okinawa was not to be another

Kiska, there was the possibility that the Marine diversion in the south had

drawn the Japanese forces to that area. While the real attack forces approached

by a roundabout route, covered by an early morning fog and artificial smoke,

the approach of the diversion troops had been in full view of the enemy. Again,

the Japanese might be conserving their strength for a bold counterattack as

soon as American forces should be irrevocably committed to the beaches; but

the time for such a counterattack came and went and still the enemy gave no

sign.

The truth was, as the Americans were

soon to discover, that the enemy was indeed on Okinawa in great strength, and

that he had a well-thought-out plan for meeting the invasion.1

The task of defending the Ryukyus was

entrusted to the Japanese 32d Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima.2

General Ushijima had assumed command in August 1944, relieving Lt. Gen. Masao

Watanabe who had activated the 32d Army in the preceding April. On assuming

command, General Ushijima and his chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Isamu Cho, had reorganized

the staff of the Army, replacing the incumbents with bright young officers

from Imperial Headquarters. As reconstituted, the staff was distinguished by

its youth, low rank, and ability. Col. Hiromichi Yahara, the only holdover from

the old staff, was retained as senior staff officer in charge of operations.

[84]

General Ushijima, according to the members

of his staff, was a calm and very capable officer who inspired confidence among

his troops. He had commanded an infantry group in Burma early in the war and

came to his new assignment from the position of Commandant of the Japanese Military

Academy at Zama. General Cho was a hard-driving, aggressive officer who had

occupied high staff positions with the troops in China, Malaya, and Burma and

had come to Okinawa from the Military Affairs Bureau of the War Department in

Tokyo. Colonel Yahara enjoyed the reputation of being a brilliant tactician,

conservative and calculating in his decisions. The combination of Ushijima's

mature judgment, Cho's supple mind and aggressive energy, and the shrewd discernment

of Yahara gave the 32d Army a balanced and impressively able high command

3

Prior to the activation of the 32d

Army on 1 April 1944, Okinawa had been defended by a small and poorly trained

garrison force. In June, before the American landings in the Marianas, the Japanese

planned to reinforce the garrison with nine infantry and three artillery battalions.4

The first reinforcement to reach Okinawa was the 44th Independent Mixed

Brigade, which arrived late in June. The 9th Division landed on

the island in July and was followed in August by the 62d Division and

the 24th Division. Artillery, supporting troops, and service elements

arrived during the summer and fall of 1944.

The Japanese plans for the defense of

the Ryukyus were disrupted when the veteran 9th Division left Okinawa

for Formosa early in December, as part of the stream of reinforcements started

toward the Philippines after the invasion of Leyte. It was intended to replace

the division, but shortage of shipping made this impossible. Of the remaining

combat units, the 62d Division was considered by the commanding general

and his staff to be the best in the 32d Army. Commanded by Lt. Gen. Takeo

Fujioka, the division was formed from the 63d and 64th Brigades,

each consisting of four independent infantry battalions which had fought in

China since 1938. It lacked divisional artillery but by April 1945 had been

brought up to a strength of about 14,000 by the addition of two independent

infantry battalions and a number of Boeitai (Okinawa Home Guards).

[85]

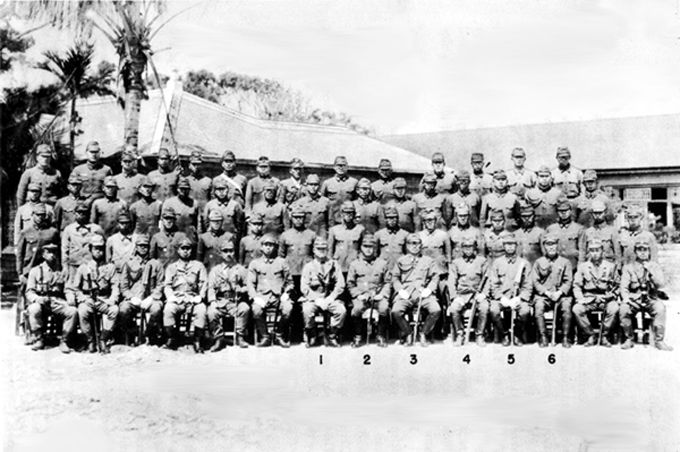

JAPANESE COMMANDERS on Okinawa (photographed early in February 1945).

In center: (1) Admiral Minoru Ota, (2) Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, (3) Lt.

Gen. Isamu Cho, (4) Col. Hitoshi Kanayama, (5) Col. Kikuji Hongo, and (6)

Col. Hiromichi Yahara.

[86]

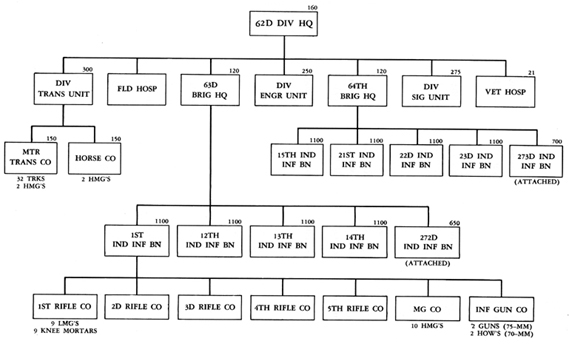

As finally organized, each of the independent

infantry battalions was composed of five rifle companies, a machine gun company,

and an infantry gun company, with a total battalion strength of approximately

1,200 men. (See Chart V.)

Unlike the 62d Division, the

24th was a triangular division, consisting of the 22d, 32d,

and 89th Infantry Regiments and the 42d Field Artillery Regiment;

it had never seen combat. In January 1945 each of the infantry regiments had

incorporated 300 Okinawan conscripts into its ranks and had been reorganized.

After the reorganization a regiment consisted of three battalions of three rifle

companies each, with each company reduced from 290 to 180 men. The total strength

of the division, including Okinawans, was more than 15,000.

The 44th Independent Mixed Brigade

consisted of the 2d Infantry Unit and the 15th Independent Mixed

Regiment and had a strength of about 5,000 men. The brigade had lost most

of its original personnel by American submarine action while en route to Okinawa

in June 1944, and it had been reconstructed around a nucleus of 600 survivors.

The latter, plus replacements from Kyushu and conscripted Okinawans, were reorganized

into the 2d Infantry Unit, of approximately regimental strength but without

a full complement of weapons and equipment. The 15th Independent Mixed Regiment

was flown to Okinawa at the end of June 1944 and assigned to the brigade. In

addition to its three battalions of infantry, it had engineering troops and

an antitank company; by the addition of native conscripts and Boeitai

it had been brought by April 1945 to a strength of almost 2,800 men.

To add to the three major combat infantry

units, General Ushijima in February 1945 converted seven sea-raiding battalions,

formed to man suicide boats, into independent battalions for duty as infantry

troops to fill the serious shortage resulting from the withdrawal of the 9th

Division. These battalions had a strength of approximately 600 men each and

were divided among the major infantry commands. Counting these additions there

was a total of thirty-one battalions of infantry on Okinawa, of which thirty

were in the southern part.

Independent artillery units constituted

an important part of the reinforcements sent to Okinawa. Two regiments of 150-mm.

howitzers, one regiment of 75-mm. and 120-mm. guns, and one heavy artillery

battalion of 150-mm- guns were on the island by the end of 1944 to supplement

the organic divisional artillery and infantry cannon. For the first time in

the Pacific war, Japanese artillery was under a unified command; all artillery

units, with the exception of divisional artillery, were under the control of

the 5th Artillery Command. Most of the personnel of the command, which numbered

3,200, had served in other cam-

[87]

Organization of the Japanese 62d Division in Okinawa

Source: Tenth Army G-2 Intelligence Monograph Ryukyus Campaign, Part I,

Sec. B, p. 20

[88]

paigns and had been with their units

for three or four years. They were well trained by Japanese standards and were

considered among the best artillerymen in the Japanese Army.

About 10,000 naval personnel were organized

into the Okinawa Naval Base Force, commanded by Rear Admiral Minoru

Ota, which had control of all naval establishments and activities in the Ryukyus.

The unit was largely concentrated on Oroku Peninsula and just before the American

landings was reorganized as a ground combat force for the defense of the peninsula.

Only about 200 of the Force, however, had had more than superficial training

in ground combat.

Other important units on Okinawa included

the 27th Tank Regiment of about 750 men, 4 independent machine gun battalions

totaling over 1,600 men, an independent mortar regiment of 600 men, 2 light

mortar battalions comprising 1,200 men, 4 antiaircraft artillery battalions

totaling 2,000 men, 3 machine cannon battalions with 1,000 men, and 3 independent

antitank battalions and 4 independent antitank companies totaling about 1,600

men. There were also from 22,000 to 23,000 service troops of various kinds.

At the time of the American landings

on Okinawa, about 20,000 Boeitai had been mobilized by the Japanese

for duty as labor and service troops. Though these men were for the most part

not armed, they performed valuable services as ammunition and supply carriers

at the front lines and also engaged in numerous front-line and rear-area construction

and other duties. Some eventually saw combat. The Boeitai are not to

be confused with the Okinawan conscripts and reservists who were called up and

assimilated into the regular army just as were the Japanese in the home islands.

The first group of Boeitai was assembled in June 1944 to work on the

construction of airfields, but the general mobilization of natives into "National

Home Defense Units" was not ordered until January 1945, after the departure

of the 9th Division. About 17,000 Okinawans between the ages of seventeen

and forty-five were drafted to serve as Boeitai. In addition, about 750

male students of the middle schools, fourteen years of age and over, were organized

into Blood and Iron for the Emperor Duty Units and trained for guerilla warfare.

Further drafts of Boeitai were made at various times during the battle.

In addition to the Boeitai a large number of Okinawan civilians were

conscripted into the Japanese forces either to increase the strength of existing

units or to organize new units. While the actual number of Okinawans serving

with the 32d Army has not been determined, available evidence indicates that

they represented a large proportion of the total,

[89]

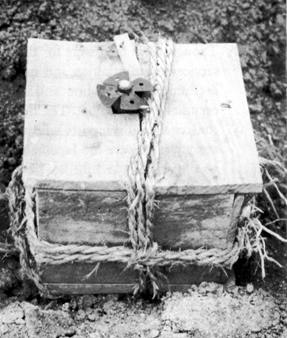

JAPANESE WEAPONS

50-mm. Grenade Discharger

|

Hand Grenade

|

320-mm. (Spigot) Mortar Shell

|

Satchel Charge

|

[90]

increasing the Japanese strength by

perhaps as much as one-third or more.5

When the Americans invaded Okinawa,

the total strength of the 32d Army amounted to more than 100,000 men,

including the 20,000 Boeitai draftees and an unknown number of conscripted

Okinawans. The army proper totaled 77,000, consisting of 39,000 Japanese troops

in infantry combat units and 38,000 in special troops, artillery, and service

units. (For the troop list of the 32d Army, see Appendix B.)

Weapons of the 32d Army

The armament of the Japanese on Okinawa

was characterized by a high proportion of artillery, mortar, antiaircraft, and

automatic weapons in relation to infantry strength. Their supply of automatic

weapons and mortars was generally in excess of authorized allotments; much of

this excess resulted from the distribution of an accumulation of such weapons

intended for shipment to the Philippines and elsewhere but prevented by the

shortage of shipping and the course of war from leaving the island. The Japanese

also had an abundant supply of ammunition, mines, hand grenades, and satchel

charges.6

On Okinawa the Japanese possessed artillery

in greater quantity, size, and variety than had been available to them in any

previous Pacific campaign. Utilizing naval coastal guns, they were able to concentrate

a total of 287 guns and howitzers of 70-mm. or larger caliber for the defense

of the island. Of this total, sixty-nine pieces could be classified as medium

artillery, including fifty-two 150-mm. howitzers and twelve 150-mm- guns. The

smaller pieces included 170 guns and howitzers of calibers of 70- and 75-mm.

In addition, seventy-two 75-mm. antiaircraft guns and fifty-four 20-mm. machine

cannon were available for use in ground missions.

The principal mortar strength of the

32d Army was represented by ninety-six 81-mm. mortars of the two light

mortar battalions. The Japanese also possessed, in greater numbers than had

previously been encountered, the large 320-mm. mortars, commonly called spigot

mortars; the 1st Artillery Mortar Regiment, reputed to be the only one

of its kind in the Japanese Army, was armed with twenty-four of these. Standard

equipment of the ground combat units of the army included about 1,100 50-mm,

grenade dischargers (knee mortars).

[91]

To counter American tank strength, the

Japanese relied, among other things, on an unusually large number of antitank

guns, especially the 47-mm. type. The independent antitank units had a total

of fifty-two 47-mm. antitank guns, while twenty-seven 37-mm. antitank guns were

distributed among the other units of the Army. The entire Japanese tank

force, however, consisted of only fourteen medium and thirteen light tanks,

the heaviest weapon of which was the 57-mm. gun mounted on the medium tanks.

The 32d Army relied heavily

on a great number of automatic weapons, well emplaced and plentifully supplied

with ammunition. Its units possessed a total of 333 heavy and 1,208 light machine

guns. In the course of the battle many more were taken from tanks being used

as pillboxes and from wrecked airplanes. The 62d Division alone wielded

nearly half the automatic weapons of the 32d Army and was by far its

most potent unit.

The active formulation of a defense

plan for the Ryukyus dates from the American capture of the Marianas in June

and July 1944. The first plan for the ground defense of the Ryukyus was established

in a 32d Army directive of 19 July 1944. This document outlined a plan

to destroy the Americans at the water's edge; that failing, to "annihilate"

them from previously constructed positions, embodying a fortified defense in

depth. In accordance with this directive, construction of cave and underground

positions began in the summer of 1944. The command on Okinawa was convinced

that the situation was urgent and informed the troops that "the Empire

is determined to fight a show-down battle with an all-out effort for the preservation

of national unity when the enemy advances to the Nansei Shoto." 7

In instructions issued in August 32d Army Headquarters stated:

The enemy counteroffensive has become

increasingly severe and they have infiltrated into our central Pacific defense

area and are now boldly aiming toward the Nansei Shoto. Should we be unable

to defend the Nansei Shoto, the mainland and the southern frontier would become

isolated. Thus, the execution of the present war would be extremely difficult

and would become a life-and-death problem for our nation. 8

In the early part of 1945 important

changes were made in the original defense plan. It was decided not to attempt

the destruction of the invading

[92]

forces at the beaches, but to have the

32d Army offer a strong resistance around a central fortified position;

a decisive land battle would be avoided until the Kamikaze planes and

the Japanese fleet should destroy the American warships and transports. The

general character of the final plan reflected the critical situation that faced

General Ushijima with the departure of the 9th Division for Formosa

and with the fading of prospects for reinforcements. He had to alter his plans

to fit his resources, so depleted by now that he had to mobilize virtually the

entire civilian population of the island.

The Japanese high command was determined

to hold Okinawa and planned to employ the major portion of the Empire's remaining

air strength as well as a large portion of its fleet in an attack on the American

sea forces. The Japanese hoped to isolate and weaken the invading ground forces

by destroying the American naval units and support shipping lying off Okinawa.

To accomplish this, they relied chiefly on bomb-laden planes guided to their

targets by suicide pilots, members of the Japanese Navy's Special Attack

Corps known as the Kamikaze (Divine Wind) Corps. This desperate

measure was expected to equalize the uneven ground battle by cutting off the

Americans from supplies and reinforcements. It would enable the 32d Army

to drive the invaders into the sea.

Despite the hopes of the Japanese high

command, planning of the 32d Army for the defense of Okinawa proceeded

on the assumption that it was impossible to defeat the enemy and that .the most

that could be done was to deny him the use of the island for as long a period

as possible and inflict the maximum number of casualties.9

Acting on this assumption, General Ushijima drew his forces together into the

southern part of Okinawa and, from the strongly fortified positions around Shuri,

prepared to make his stand there as costly to the enemy as possible. He would

not go out to meet the invaders; he would wait for them to come to him, and

force them to fight on his own terms. The 32d Army artillery was instructed

not to fire on the invading ships and landing forces, in order to avoid revealing

its positions and exposing them to the devastating naval gunfire of the Americans.

Units were not to oppose landings in their sectors until enough enemy troops

had been brought ashore to render escape by sea impossible. The 32d Army

planned to defend only the southern third of Okinawa strongly. The principal

defenses would be established in the rugged ground north of Naha, Shuri, and

Yonabaru. Landings north of this line would not be opposed; south of it the

Americans would be met on the beaches.

[93]

Wherever the Americans landed, they

would eventually come up against the Shuri defenses, where the main battle would

be fought.10

The Japanese estimate of American plans

was very accurate. The enemy expected the Americans to land across the Hagushi

beaches on the west coast, with from six to ten divisions, and to strike out

for the Yontan and Kadena airfields. He anticipated that American landing forces

would form large beachheads of 2-division strength each, hold within these perimeters

until sufficient supplies were unloaded to permit a strong attack, and then

advance behind massed tanks and concentrated artillery fire. The Japanese estimated

that it would take the Americans about ten days to launch their attack against

the main Shuri defenses. They believed that the Americans intended to draw the

main Japanese force into the Shuri lines so that a not too costly secondary

landing could be effected with perhaps one division on the east coast somewhere

south of Shuri, near Minatoga.11

The 32d Army disposed its available

troops in accordance with its general plan of defense and its estimate of the

enemy's capabilities. Only two battalions of the 2d Infantry Unit were

left in the north to defend not only the Motobu Peninsula but also Ie Shima,

where they destroyed the island's airfield.12

The only force stationed in the area immediately behind the Hagushi beaches

was the 1st Specially Established Regiment, Boeitai, which was ordered to fight

a delaying action and then, after destroying the two airfields in the sector,

to retreat.13

The 62d Division manned the defensive belt across the island north of

the Naha Shuri-Yonabaru line. Its 63d Brigade was to absorb the shock

of the American attack southward at the narrow waist of the island between Chatan

and Toguchi, while the main line of resistance was established from Uchitomari

to Tsuwa north of the Shuri defenses. Deployed to support the 63d, the

64th Brigade was dug in to fight in the successive positions around

Shuri. Artillery attached to the 62d Division was emplaced in direct

support on the west side of the line.14

(See Map No. VI.)

[94]

Having selected the Shuri area as their

main battle position, the Japanese with shrewdness and great industry organized

the ground for a strong defense. The main zone of defense was planned as a series

of concentric positions adapted to the contours of the area. Caves, emplacements,

blockhouses, and pillboxes were built into the hills and escarpments, connected

by elaborate underground tunnels and skillfully camouflaged; many of the burial

tombs were fortified. The Japanese took full advantage of the terrain to organize

defensive areas and strong points that were mutually supporting, and they fortified

the reverse as well as the forward slopes of hills. Artillery and mortars were

emplaced in the caves and thoroughly integrated into the general scheme of defensive

fires.15

To meet the threat of landings in the

south, the 32d Army stationed the 24th Division in defensive

positions covering the Minatoga beaches and extending across the southern end

of the island.16

The 44th Independent Mixed Brigade was moved to the Chinen Peninsula

and was ordered to cooperate with the 24th Division in repelling any

landings in the area. Artillery was registered on the Minatoga beaches, and

some of the 320-mm. mortars were moved to this sector.17

During the long period of planning the

Imperial General Staff and the 32d Army were constantly concerned with

fixing the probable date of the American invasion; each changed its view several

times and on occasion they were not in agreement. It was during and after the

invasion of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam, in the summer of 1944, that the Japanese

first expected an immediate invasion of Okinawa and, accordingly, began to pour

troops into the island. But after the invasion of the Palaus and Leyte in September

and October 1944 the Imperial General Staff in Tokyo considered it unlikely

that sufficient American troops would be immediately available for another major

operation.18

During the Philippines operations at the end of 1944 the Imperial General Staff

in Tokyo was in doubt as to whether the next blow would fall on the south China

coast or on Formosa,19

although the command of the 32d Army was still convinced that Okinawa

would be invaded and pushed forward preparations for its defense.20

[95]

Again, at the beginning of 1945 the

Imperial General Staff was uncertain whether the next American attack would

be against Formosa or Okinawa. By the end of February, as a result of the invasion

of Iwo Jima, which pointed to the American strategy of cutting off the Japanese

home islands from the mainland and the Indies, the Japanese concluded that Formosa

would be bypassed and that Okinawa would be the next target.21

Their aerial reconnaissance and intelligence reports revealed an increase in

west-bound American shipping to the Philippines and the Marianas during the

latter part of February--an increase that swelled to large proportions early

in March; this seemed a clear indication of the imminence of another American

operation.22

When the invasion fleet appeared off Iwo Jima, it was considered by some to

be a feint for the invasion of Okinawa.23

With the Iwo Jima battle in progress and submarine activity increasing around

the Ryukyus, it was taken for granted that the invasion of Okinawa would soon

follow, on or about 1 April 1945 24

As one of the last steps in preparing

for the expected struggle, the Japanese command on Okinawa on 21 March ordered

all air, shipping, and rear-echelon units to "prepare for ground combat."

On 27 March, the day after the American invasion of the Keramas, 32d Army

advised its units that "the enemy is planning to land his main strength

tomorrow, the 28th, on the western coast of southern Okinawa, in particular

in the Yontan-Kadena sector." 25

When the American forces invaded Okinawa, a few days later than had been predicted,

the 32d Army adhered strictly to its plan of offering little resistance

until the invaders should come up against their outposts at the Shuri line.

The Japanese Combined Fleet Commander, meanwhile, prepared to execute his plan,

delayed by Task Force 58's foray into the Inland Sea in March, to destroy the

American fleet by air and surface action. Before many days had passed, the enemy

was to react to the invasion with a fury never before encountered.

The American command was aware of the

likelihood of formidable attacks by both air and sea on the assault forces.

Okinawa was close to the Japanese home-

[96]

land, where the remaining strength of

the enemy's naval and air forces was concentrated. To meet the expected air

offensive from the near-by fields of Kyushu. Shanghai, and Formosa, the Americans

relied upon Task Force 58, the Tenth Army's Tactical Air Force, the guns of

the fleet and supply ships, the British task force, and land-based antiaircraft

artillery. To ensure early warning of Japanese raids, the Navy established around

Okinawa a ring of picket stations, manned by destroyers and destroyer-type vessels,

to which gunboats (LCS) and later LSM(R) types were added to give increased

fire power. These stations were all less than 100 miles from Zampa Point, the

peninsula just north of the Marine beaches; some, were only a few miles off

the coasts of the island. Combat air patrols were maintained day and night over

the picket stations, which could also call for aid from the routine combat air

patrol of from 48 to 120 planes aloft during the daytime, orbiting in depth

in a circle around Okinawa. Task Force 58, deployed just to the east of Okinawa,

with its own picket group of from 6 to 8 destroyers, kept 13 carriers (7 CV

and 6 CVL) on duty from 23 March to 27 April and a smaller number thereafter.

Until 27 April from 14 to 18 converted carriers (CVE's) were in the area at

all times, and until 20 April British Task Force 57, with 4 large and 6 converted

carriers, remained off the Sakishima Islands to protect the southern flank.

Two Marine Fighter Groups were installed and operating at Yontan and Kadena

airfields by 9 April, and other Marine and Army Air Groups were added later.

All assault antiaircraft artillery of the XXIV Corps was ashore by the night

of 4 April, and that of III Amphibious Corps by 12 April. Japanese airmen were

to find these combined defenses formidable.26

Enemy air opposition had been relatively

light during the first few days after the landings. On 6 April the expected

air reaction materialized with a fierce attack of 400 planes which had flown

down from Kyushu to drive the invaders from Okinawa. The raids' began at dawn,

and by noon Task Force 58 had shot down seven possible suicide planes. Throughout

the afternoon the battle increased in intensity. Patrol and picket ships, which

throughout the operation proved an irresistible attraction to enemy planes,

were a favorite target. Japanese planes also appeared from time to time over

the Hagushi beaches and transport area and were taken under fire by the ship

and shore

[97]

KAMIKAZE ATTACKS resulted in many hits, more near

misses. U. S. S. Sangamon (above) was just missed but was hit in

a later attack. Another near miss (below) sent U. S. battleship Missouri's

gunners scurrying from upper turret while those in Turret 9 looked to see

what was going on.

[98]

batteries. On such occasions the raider,

ringed with bright streams of tracer bullets from automatic weapons, would streak

across a sky filled with black puffs of smoke from hundreds of bursting shells,

and in the course of seconds would plunge into the sea in a geyser of water

and smoke, or crash into a ship with an even greater explosion of smoke and

flame. Directed against such raiders, friendly fire killed four Americans and

wounded thirty-four others in the XXIV Corps zone, ignited an ammunition dump

near Kadena, destroyed an oil barge, and in the late afternoon shot down two

American planes over the beaches. Some ships also suffered damage and casualties

from friendly fire. Twenty-two of twenty-four suicide crashes were successful,

sinking two destroyers, a mine sweeper, two ammunition ships, and an LST. A

ship rescuing survivors from the lost LST was itself struck by a suicide plane

soon after but was not seriously damaged. The attack cost the Japanese about

300 planes; 65 were splashed by fliers from the Essex alone. Unloading

continued on the Hagushi beaches almost without pause, and the American fleet,

although it had taken severe blows, was still intact.27

On the night of 6-7 April the Japanese

fleet came out for the planned surface attack on the American sea forces. An

American submarine lying off Kyushu reported the movement of the Japanese warships,

and forty planes of Task Force 58 began a far-flung search at dawn on 7 April.

At 0822 a plane from the Essex sighted the enemy force, which consisted of the

battleship Yamato, the light cruiser Yahagi, and eight destroyers,

in the East China Sea on a course toward Okinawa. Task Force 58, which had started

northeastward at 0400 that morning in order to close with the enemy, launched

its planes at a point estimated to be 240 miles from the enemy fleet. The. first

attacks through heavy but inaccurate antiaircraft fire scored at least eight

torpedo and five bomb hits on the Yamato, the Yahagi, and three

of the destroyers. Subsequent attacks succeeded in sinking the Yamato,

the Yahagi, and four destroyers; one destroyer was seriously damaged

and one left burning. Task Force 58 lost only 10 planes out of the 386 that

participated. Okinawa was now safe from surface attack.28

While the strike on the Yamato

was in progress, Task Force 58 was busy warding off enemy air attacks and in

the course of the day shot down fifty-four planes. A suicide plane dropped its

bomb from a height of fifty feet onto the Hancock's flight deck, then itself

plowed through a group of planes aft. Although

[99]

SINKING OF THE YAMATO, last of Japan's super-battleships, was accomplished

by Task Force 58 before the Yamato had ever fired her main batteries

in World War II. With her escorts near by, she went up in a blast of smoke

and flame.

[100]

seriously damaged, the carrier landed

her own planes when they returned at i63o. British Task Force 57 was able to

keep the airfields of Sakishima largely inoperative during the Japanese air

and sea offensive of 6-7 April.29

The enemy continued during April to

deliver periodic heavy air attacks. Daytime raids were generally staged against

Task Force 58, the picket ships, and shipping beyond the range of land-based

antiaircraft artillery. At night, when the supply ships shrouded themselves

in artificial fog as raiders approached, the enemy usually struck Yontan and

Kadena airfields, with the Hagushi beaches a secondary target. Most of these

raids were made between 2100 and 2300, and 0200 and 0400. The Japanese, clever

at deception, sometimes shelled one of the airfields with their artillery, leading

the Americans to expect an attack at that point, and then followed with an air

raid on the other field. On occasion enemy planes would follow American planes

in at dusk, circle the fields with their lights on, and then bomb and strafe

the runways and storage areas.30

Task Force 58 was heavily engaged on

it April, and near misses by four suicide planes sent the carrier Enterprise

to Ulithi for repairs. On the next day the main weight of the attack shifted

to the picket ships and the Hagushi anchorage. Seventeen Allied ships were hit

and two sunk. The destroyer M. L. Abele was sent to the bottom when hit by both

a suicide plane and a Baka bomb; the latter was a potentially dangerous but

not often successful piloted, rocket-driven projectile launched by a twin-engined

bomber. Again on 25-16 April, despite strikes by Task Force 58 against Kyushu

airfields, Japanese airplanes appeared in strength at Okinawa. On the 16th a

Kamikaze plane crashed the Intrepid's flight deck, and other

suicide planes damaged 10 ships and sank a destroyer; 270 enemy planes were

shot from the air and many more destroyed on the ground. Eventful days, too,

were 22, 27, and 28 April. On the last of these, starting at 1400, a force of

200 Japanese planes attacked Okinawa in 44 raids. Several American ships were

damaged, but 118 of the attacking planes were destroyed. The hospital ship Comfort,

although following hospital procedure, was crashed by a suicide plane 50 miles

south of Okinawa. The Comfort's casualty list was 63, of whom 29 were

killed and 1 missing.31

American planes too had struck hard.

During the month the XXI Bomber Command had hit Japan with 15,712 tons of bombs;

36 percent of the tonnage

[101]

had been dropped on Kyushu airfields

in support of the Okinawa operation, 29 percent on the Japanese aircraft industry,

and 34 percent on other Japanese urban industrial areas. Formosa was being struck

from the Philippines.

During the period 26 March-30 April,

20 American ships were sunk and 157 damaged by enemy action. Suicide attacks

accounted for the sinking of 14 ships and the damaging of 90, while other air

attacks damaged 47 ships and sank 1. Two of the largest carriers-the Hancock

and the Enterprise-one CVL, the San Jacinto, and the British

carrier Intrepid sustained serious damage from suicide planes. Picket

ships suffered especially heavy attrition, and as quickly as land-based radar

could be installed on Okinawa and neighboring islands the number of picket stations

was reduced. Five picket stations remained after completion of radar installations

at Hedo Point on 21 April and in Ie Shima on 23 April. Although the seizure

of the Kerama Islands had substantially reduced this threat, suicide boats continued

to be active on a small scale, particularly in the Naha and Yonabaru areas at

night. Up to 30 April suicide boats sank one ship and damaged six. Navy casualties

were heavy; during April they totaled 956 killed, 2,650 wounded, and 897 missing

in action.32

For their part, the Japanese had lost

up to 30 April more than 1,100 planes in the battle to Allied naval forces alone,

and many more to land-based antiaircraft artillery and planes of the Tactical

Air Force. Not only had the task force led by the Yamato been defeated

and for the most part sunk, but a considerable number of other Japanese combatant

and auxiliary vessels had also been sunk or damaged.

More important, the Japanese plan to

destroy or drive off the fleet and isolate the troops, thus winning the battle

for Okinawa, had been frustrated. Instead, the Japanese on the island were completely

cut off and isolated from their near-by homeland. The invading warships and

transports remained and, despite the weight of the blows delivered against them,

continued to pour supplies into Okinawa and to keep the lanes open for fresh

supplies from the other side of the Pacific Ocean. Thus American ground troops

could work their way inland with the assurance of an unbroken supply line.33

[102]

page created 10 December 2001

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents