- Chapter XIV:

-

- Battle in the Rain

-

- At the end of the third week of May

the fighting had penetrated to the inner ring of the Shuri defenses. The Tenth

Army's hopes had been raised by the capture of the eastern slopes of Conical

Hill, which, permitting the 7th Division to funnel through the corridor by

Buckner Bay, opened up the possibility of an envelopment of the enemy forces.

But the bid for envelopment was destined to fail. From 22 to 29 May, except

for certain gains on the flanks, there was no appreciable progress against

any part of the Japanese inner defense ring. The enemy line held with hardly

a dent against every attack.

-

- The stalemate was due in large measure

to rain, mud, and the bogging down of all heavy equipment. The weather during

April and thus far into May had been unexpectedly good; there had been far

less rain than preinvasion meteorological tables had predicted. But now the

days of grace from the skies were over: the heavens were about to open and

the much talked-about "plum rains" of Okinawa were to set in and

continue day after day. Mud was to become king, and it was impossible to mount

a large-scale attack during this period.

-

-

- While the ground fighting was largely

stalemated by rain, the air battle between the Americans on Okinawa and the

enemy pilots from the Japanese home islands went on unceasingly. Despite their

failure in April to destroy the invading American fleet, the Japanese air

forces in May kept on unremittingly with their attacks. They were directed

against two targets-the ships off shore and the airfields on Ie Shima and

at Yontan and Kadena. During the latter half of May the Japanese air attacks

on these targets reached a peak and included some of the severest strikes

which the enemy delivered during the air fighting of the entire campaign.

The American Tactical Air Force not only engaged in routine support of the

ground forces-a support limited in effectiveness by the location of the enemy

in deep underground positions-but also attempted to ward off the Japanese

air attacks from the home islands. Thunderbolts and Corsairs

- [360]

- of the Tactical Air Force made daily

sweeps over the waters between Okinawa and southern Kyushu, intercepting enemy

planes, and often continuing over Kyushu to bomb, rocket, and strafe targets

there. From Guam, Saipan, and Tinian in the Marianas the strategic heavy bombing

of the Japanese home islands went on concurrently without let-up.1

-

- Japanese air raids reached a peak

during the latter part of May. On the 20th, thirty-five planes raided the

American fleet; twenty-three were shot down. On 22 and 23 May, Japanese planes

came over Okinawa again. Beginning on 24 May, the enemy stepped up the tempo

of the attack on American units ashore and afloat. The evening of the 24th

was perfect bombing weather with a clear sky and full moon. The air alerts

started about 2000 and it was 2400 before an all-clear sounded. In that interval

there were seven distinct air raids on Okinawa. In the first raid planes penetrated

through to bomb Yontan and Kadena. The third, fourth, and sixth groups of

raiders also succeeded in dropping bombs on the airfields.

-

- The seventh group consisted of five

low-flying two-engine bombers, called "Sallys," that came in about

2230 from the direction of Ie Shima. Antiaircraft batteries immediately engaged

them, and four planes crashed in flames near Yontan airfield. The fifth came

in and made a belly landing, wheels up, on the northeast-southwest runway

of Yontan. At least eight heavily armed Japanese rushed out of the plane and

began tossing grenades and incendiaries into American aircraft parked along

the runway. They destroyed 2 Corsairs, 4 C-54 transports, and 1 Privateer.

Twenty-six other planes-1 Liberator bomber, 3 Hellcats, and 22 Corsairs-were

damaged.

-

- In the wild confusion that followed

the landing of the Japanese airborne troops, two Americans were killed and

eighteen injured. At 2338, forces arrived at Yontan to bolster the air-ground

service units and to be on hand if enemy airborne troops made subsequent attempts

to land. In addition to the thirty-three planes destroyed and damaged, two

600-drum fuel dumps containing 70,000 gallons of gasoline were ignited and

destroyed by the Japanese. When a final survey could be made, it was found

that ten Japanese had been killed at Yontan; three others were found dead

in the plane, evidently killed

- [361]

- by antiaircraft fire. The other four

"Sallys" each carried fourteen Japanese soldiers, all of whom died

in the flaming wrecks. Sixty-nine bodies in all were counted. A Japanese soldier

killed at Zampa Point the next day was thought to be the last of the airborne

raiders. Yontan airfield was non-operational until 0800 of 25 May because

of the debris on the runway. This was the enemy's only attempt to land airborne

troops on Okinawa during the battle.

-

- While the attack on Yontan was in

progress, twenty-three enemy planes conducted a raid against the field at

le Shima. The bombing did not seriously damage the field itself but caused

sixty casualties. During the night, antiaircraft fire shot down eleven enemy

planes over Okinawa and sixteen over le Shima.

-

- The air assault of 24-25 May was not

confined to the airfields of Okinawa and le Shima. At the same time a large

Kamikaze attack was under way against American ships. It was estimated the

next day that 200 enemy planes had engaged in the attack. The enemy scored

thirteen Kamikaze hits on twelve ships off shore. In repelling an attack during

the morning of 25 May, American fighter planes intercepted and destroyed seventy-five

enemy planes north of Okinawa. Altogether, on 24-25 May, more than 170 Japanese

planes were brought down. During the week ending 26 May, the Japanese lost

at least 193 planes in the Okinawa area.

-

- The period of torrential rains was

interrupted on 27-28 May by a night of clear weather with a bright moon. The

Japanese air force and Kamikazes again came in force. Between 0730 of 27 May

and 0830 of 28 May there were 56 raids of from 2 to 4 planes each, the total

of enemy planes being estimated at 150. A vigorous effort was made by the

enemy to penetrate the transport defense area and reach the heavy ships. The

Kamikazes struck at both the Hagushi area and at Buckner Bay, which was now

coming into use as an important anchorage. During the night of 27-28 May nine

ships were hit by Kamikazes. One of them, the destroyer Drexler, hit at 0705

on 28 May, sank within two minutes. Including the Kamikazes, 114 enemy planes

were destroyed during this attack. There were only two other Kamikaze attacks

during the rest of the campaign, at the beginning and the end of June, both

of much smaller scale than any preceding.

-

- The total Japanese air effort was

far greater than that encountered in any other Pacific operation. The proximity

of airfields in Kyushu and Formosa permitted the employment by the enemy

of all types of planes and pilots. Altogether, there were 896 air raids against

Okinawa. Approximately 4,000 Japanese planes were destroyed in combat, 1,900

of which were suicide planes. The intensity and

- [362]

-

- JAPANESE AIR RAIDS ON OKINAWA were stepped up the

last week of May. Above, Japanese plane caught squarely by antiaircraft

fire leaves a trail of smoke and flame as it falls toward the ocean. Picture

below was taken after unsuccessful Japanese airborne raid on Yontan airfield

the morning of 225 May. Bodies of the enemy "Commandos" are

scattered around wreckage of their planes. torn fuselage of one "Sally"

is in left background.

-

-

- [363]

- scale of the Japanese suicide air

attacks on naval forces and shipping were the most spectacular aspects of

the Okinawa campaign. Between 6 April and 22 June there were ten organized

Kamikaze attacks, employing a total of 1,465 planes as shown below: 2

-

| Date of Attack |

Total |

Navy Planes |

Army Planes |

| 6-7 April |

355 |

230 |

125 |

| 12-13 April |

185 |

125 |

60 |

| 15-15 April |

165 |

120 |

45 |

| 27-28 April |

115 |

65 |

50 |

| 3-4 May |

125 |

75 |

50 |

| 10-11 May |

150 |

70 |

80 |

| 24-25 May |

165 |

65 |

100 |

| 27-28 May |

110 |

60 |

50 |

| 3-7 June |

50 |

20 |

30 |

| 21-22 June |

42 |

30 |

15 |

|

TOTAL

|

1465 |

860 |

605 |

-

- In addition, sporadic small-scale

suicide attacks were directed against the American fleet by both Army and

Navy planes, bringing the total number of suicide sorties during the campaign

to 1,900.

-

- The violence of the air attacks is

indicated by the damage inflicted on the American forces. Twenty-eight ships

were sunk and 225 damaged by Japanese air action during the campaign. Destroyers

sustained more hits than any other class of ships. Battleships, cruisers,

and carriers also were among those struck, some of the big naval ships suffering

heavy damage with great loss of life. The radar picket ships, made up principally

of destroyers and destroyer escorts, suffered proportionately greater losses

than any other part of the fleet. The great majority of ships sunk or damaged

were victims of the Kamikaze. Suicide planes accounted for 26 of the 28 vessels

sunk and for 164 of the 225 damaged by air attack during the entire campaign.

-

-

- It was in the center, where during

the preceding week the Americans had made least progress, that the impeding

effect of the rains of the last week in May was most clearly shown. Having

gained no break-through or momentum in the

- [364]

- previous fighting, the troops found

it impossible under the conditions to resume the offensive effectively.

-

- On the morning of 22 May the 1st Marine

Division held a line which extended over the northern and southern slopes

of Wana Ridge, south through the village of Wana. To its left, holding the

western flank of the XXIV Corps line, was the 77th Division, which had just

secured Chocolate Drop. Left of the 77th Division, the 96th Division had recently

completed the capture of Sugar Hill and was on the slopes of Oboe. (See Map

No. XLIV.)

-

- The 1st Marine Division at Wana

Ridge and Wana Draw

- When the heavy rains began the 1st

Marines was on the northern slope of Wana Ridge, at the left (east) flank

of the III Amphibious Corps. The 5th Marines was on the division right, holding

the lower crest of Wana Ridge, with its line extending on over the southern

slope into Wana village. Beyond the village of Wana lay Wana Draw, a broad,

shallow basin, entirely bare, which dropped down from the coral heights west

of northern Shuri to the Asa River and the coastal plain north of Naha. On

the south side of Wana Draw a high coral ridge, similar to Wana Ridge on the

north, climbed steeply to Shuri Heights at the southwestern corner of Shuri.

Wana Draw was completely exposed to enemy fire from high ground on three sides.

-

- The 1st Marine Division had been repeatedly

thrown back since its first attack on Wana Ridge, 13 May.3

Yet during most of this 9-day period the weather had been dry and the ground

solid, making possible a coordinated attack of all arms-infantry, tanks, heavy

assault guns, armored flame throwers, and airplanes. On 21 May the weather

changed, with gusts of wind and an overcast that reduced visibility. Before

dawn of the next day the rain began, and it continued throughout most of the

day and on into the night. The prospects of success for the infantry alone,

slogging through the mud without the support of other arms, were not encouraging.

-

- The almost continual downpour filled

Wana Draw with mud and water until it resembled a lake. Tanks bogged down,

helplessly mired. Amphibian tractors were unable to negotiate the morass,

and front-line units, which had depended on these vehicles for carrying supplies

forward in bad weather, now had to resort to hand carrying of supplies and

of the wounded. These were backbreaking tasks and were performed over areas

swept by enemy fire. Mortar and

- [365]

- artillery smoke was used as far as

possible to give concealment for all movement. Litter cases were carried back

through knee-deep mud.

-

- Living conditions of front-line troops

were indescribably bad. Foxholes dug into the clay slopes caved in from the

constant soaking, and, even when the sides held, the holes had to be bailed

out repeatedly. Clothes and equipment and the men's bodies were wet for days.

The bodies of Japanese killed at night lay outside the foxholes, decomposing

under swarms of flies. Sanitation measures broke down. The troops were often

hungry. Sleep was almost impossible. The strain began to take a mounting toll

of men.

-

- Under these conditions the Marine

attack against Wana Ridge was soon at a standstill. The action degenerated

into what was called in official reports "aggressive patrolling."

Despite inactivity, enemy mortar and artillery fire continued to play against

the American front lines, especially at dusk and at night.

-

- A break in the weather came on the

morning of 28 May. The sky was clear. The 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, acting

on a favorable report of a patrol that had reconnoitered the ground the day

before, made ready to strike for 100 Meter Hill, or Knob Hill as it was sometimes

called, at the eastern tip of Wana Ridge. As soon as this objective was gained,

the 3d Battalion was to secure Wana Draw. Twice the ad Battalion assaulted

100 Meter Hill, and by 0800 Company E reached the top. But the crest could

not be held, and no gain at all was made down the southern and eastern slopes.

Machine-gun fire from three directions hit the marines, mortar shells fell

on them, and Japanese only a few yards away mounted satchel charges on sticks

and flung them from close range. The attack failed, and smoke had to be employed

to evacuate the wounded.

- Meanwhile, on 28 May, the 5th Marines

on the division right captured Beehive Hill, a strong enemy defense position

on the lower end of Shuri Ridge south of Wana Draw.

-

- The 77th Division Stands Still

at Shuri

- The 77th Division fared no better

than did the 1st Marine Division. Its capture on 20 May of Flattop and the

Chocolate Drop area was followed very quickly by the onset of the heavy rains.

Thereafter the 77th Division made hardly any gains in its part of the line,

directly in front of Shuri. Here the Japanese stood more stubbornly, if possible,

than anywhere else, and held defiantly every muddy knob and slope. Jane (also

called "Three Sisters"), Dorothy, and Tom Hills formed the main

strong points directly north and east of Shuri from which the enemy faced

the 77th Division across the rain-drenched country. Dorothy Hill was a fortress

with several layers of caves and tunnels

- [366]

-

- WANA DRAW, from east end of Wana Ridge, showing

open ground over which marines advanced. Bottom of draw, with town of

Wana 100 feet to the right, was flooded at time of the battle. Below is

ground over which marines attacked 28 May. They captured "Beehive"

but were unable to hold "Knob". Ruins of Ishimmi, east of the

Marine zone, are at upper right.

-

-

- [367]

-

- MUD AND FLOOD increased the difficulties of fighting

on Okinawa. Above, 77th Division infantrymen trudge toward the front lines

past mud-clogged tanks. Below, 1st Division marines resort to hand carrying

of supplies and wounded as roads are washed out by torrential rains.

-

-

- [368]

- on its reverse slope and with heavy

artillery and mortars concentrated behind its protecting bulk. The next objective

of the 307th Infantry of the 77th Division was the Three Sisters, 900 yards

across a low bare swale from Flattop. Farther to the west the 306th Infantry,

which had relieved the 305th Infantry on 21 May, stood on Ishimmi Ridge and

in front of the eastern end of Wana Ridge, which had proved so tough a barrier

to the 1st Marine Division.

-

- As a result of an ill-fated attack

early in the morning of 21 May, Company A of the 307th Infantry was isolated

along the bottom of the forward slope of Jane Hill, ahead of the rest of the

troops back on Flattop and Ishimmi Ridge, with an exposed valley raked by

enemy mortar and machine-gun fire between the troops and their base of supplies.

All roads leading to the 307th front had become impassable, and over the last

2,000 yards everything had to be hand carried. As many men were lost in trying

to bring supplies up to Company A across this muddy swale as were lost in

the fighting on Jane Hill.4

In these circumstances life was not pleasant on the lower slope of the hill,

where foxholes were washed out in the yellow clay almost daily. Company A

was virtually cut off at Jane Hill from 21 to 30 May.

-

- The last week of May points up the

importance of logistics to the battle. In this instance, mud defeated local

logistics. Ammunition, water, and food had to be hand carried up from the

rear for distances as great as a mile. Casualties had to be carried back,

eight men struggling and slipping in mud up to their knees with each litter.

Weapons were dirty and wet. In a second or two, mortar shells could be expended

that had taken a man a half-day to bring to the weapon from the nearest vehicle

or dump. Under these conditions there could be no attack. The men had all

they could do to live. Their time was entirely taken in meeting the fundamental

needs of existence. Hard fighting during the last third of May was impossible

for men who were already exhausted. The troops simply tried to stay where

they were. The front had everywhere bogged down in mud.

-

- The 96th Division at Oboe

- Like the 77th Division troops, elements

of the 382d Infantry, 96th Division, holding positions at the foot of Hen

Hill, just across the boundary from the 77th Division, were unable to move

from their mud foxholes. The Japanese had perfect observation of this area

from Tom Hill, just east of Shuri, and brought down mortar and machine-gun

fire on any activity. There was little

- [369]

- movement except for an occasional

patrol. Mud, low supplies, and drooping spirits prevailed here too.

-

- To the east the lines of the 382d

Infantry crossed over the jaw-like clay promontory of Oboe, which stood like

a rampart a thousand yards east of Shuri. On 21 May bitter fighting had placed

elements of the 382d Infantry on the lip of Oboe. For the next week the crest

of Oboe was a no-man's land, and around it, and even down the forward face,

supposedly in American hands, a close and unending grenade and bitter hand-to-hand

fight raged. Here, more than anywhere else on the cross-island line during

the period of mud, action was always near at hand. Here it was hardest to

maintain the status quo described by Lt. Col. Howard L. Cornutt, Assistant

G-3 of the 96th Division, when he stated ironically: "Those on the forward

slopes of hills slid down; those on the reverse slopes slid back. Otherwise,

no change." 5

-

- An hour after midnight, in the morning

of 24 May, a platoon of Japanese started through a gap between Companies C

and L on Oboe and succeeded in knocking out the three right-hand foxholes

of Company C. The light mortars of the 1st Battalion were at the base of Oboe,

and when the attack developed they fired into the gap between the companies

for the next four hours at the rate of a round and a half a minute. Communication

lines were out: enemy mortars had cut every phone line, and the radio to the

Navy had been drowned out by the rain. Artillery and illumination by the Navy

could not be called over the area. By 0330 a full company of Japanese was

attacking through the gap, and two platoons were assaulting Company A on the

left of Company C. In the foxhole next to the three that had been knocked

out by the Japanese, Pfc. Delmar Schriever, though wounded by mortar fire

which killed the other two men in the foxhole with him, held his position

single-handed until morning. Companies A and B were forced back off Oboe to

the bottom, but the few men left in Company C remained near the top under

the courageous leadership of Pfc. John J. Kwiecien, who took over command

of the 1st Platoon when the platoon leader was wounded. In the 2d Platoon

on the right only one man out of fourteen was unwounded when daylight came.

These men on Oboe had used thirty-five cases of grenades during the night;

only fifty rounds of 60-mm. mortar remained. By 0530 the foxholes on the right

of Company C at the crest of Oboe had been won back from the Japanese. At

this time Japanese were seen

- [370]

- "THREE SISTERS," photographed 6 May after the

area had been saturated by American artillery fire. Radio towers (upper

left) were destroyed later in May.

-

- OBOE hill mass was under attack by the 77th Division artillery when

this picture was taken 23 May. Muddy reverse slope of Zebra (foreground)

is pitted with Foxholes; some shelters can be seen in defilable at foot

of Oboe.

-

- [371]

- forming for another attack, but a

timely resupply of mortar ammunition enabled the embattled troops to repel

this effort. During the Japanese counterattack against Oboe the 362d Field

Artillery Battalion fired 560 rounds of shells in helping to stem the enemy

onslaught.

-

- When the Japanese attack subsided,

150 enemy dead lay on top of Oboe and on the slope immediately beyond. The

Japanese dug in on the reverse slope of Oboe only twenty-five yards from the

American foxholes. Between the two dug-in forces, on 24 May, there was an

interchange of hand grenades all day long.

-

- The heavy losses incurred by the 1st

Battalion, 382d Infantry, in repelling this furious Japanese night assault

compelled a reorganization of the battalion. The three rifle companies, A,

B, and C, were combined into one company under the Company C commander, with

a total strength of 198 officers and enlisted men. This is another example

of how battalions were reduced to company strength at Shuri. On 24 May General

Bradley, the 96th Division commander, ordered the 3d Battalion, 383d Infantry,

to take over the left part of the line of the 2d Battalion, 382d, on Oboe.

The ranks of the 2d Battalion had become too thin to withstand another attack

like that of 24 May.

-

- Efforts of the 383d Infantry to make

inroads into the Love Hill system of defenses on the western side of Conical

all failed during the period 22-28 May. Many men were killed during patrol

action while searching for a weak spot in the enemy's lines. Nor could American

troops move over the crest of the Conical hogback to the west slope without

risking their lives. In the neighborhood of Cutaway Hill especially, the enemy

constantly reinforced his lines and kept on the alert. No gains toward Shuri

were registered in any part of this region lying west of the crest of Conical.

The enemy held tight. Thus matters stood along the center of the XXIV Corps

front at the end of the month of May.

-

-

- During the rainy period at the end

of May, both flanks of the American line forged ahead of the center. This

development was a continuation of a trend that had started in the third week

of May. In that week two ramparts of the three hills that made up the integrated

Sugar Loaf position-Sugar Loaf itself and the Horseshoe-had fallen after as

bloody a period of fighting as the marines had ever encountered. However,

the efforts of the 6th Marine Division to complete the reduction of Sugar

Loaf, the left (west) anchor of the Japanese

- [372]

- line, failed; on 21 May, after five

days of fighting, they gave up their attempt to take the reverse (south) slope

of the Crescent, the third and closest to Shuri of the Sugar Loaf hills.

-

- For several days after Sugar Loaf

fell, the 6th Marine Division continued its efforts to reduce Crescent, the

easternmost strong point of the Sugar Loaf sector, but without success. The

Japanese denied American troops control of the crest and retained complete

possession of the crescent-shaped reverse slope. As long as this ground remained

in Japanese hands there could be no swinging eastward by the 6th Marine Division

for close envelopment of Shuri. After considering the prospect the division

decided to abandon its efforts to force the fall of Crescent and instead to

press on toward Naha and the Kokuba River. A strong defense force was left

on the north face of Crescent to protect the left rear and to maintain contact

with the 1st Marine Division to the east. The main effort of the Army's right

(west) flank was now toward Naha and no longer immediately toward Shuri.6

-

- The 6th Marine Division Crosses

the Asato

- The heavy rains had raised the Asato

River when patrols on the night of 22-23 May waded the river upstream from

Naha to reconnoiter the south bank. The initial reports were that it would

be feasible to cross the stream without tank support. Between dawn and 1000,

23 May, patrols pressed 400 yards south of the river under moderate fire.

At 1000 the decision was made to cross in force at 1200 by infiltration. An

hour and a half after the movement began two battalions were across the Asato

under cover of smoke. Casualties had to be evacuated back across the stream

by hand, twelve men carrying each stretcher in chest-deep water.

-

- Throughout the night of 23-24 May

the 6th Engineer Battalion labored to build a crossing for vehicles. Borrowing

from experience at Guadalcanal, five LVT's were brought to the stream and

efforts made to move them into position to serve as piers for bridge timbers.

Two of the LVT's struck mines along the bank and were destroyed, and the effort

to bridge the stream in this manner was abandoned. At dawn a Bailey bridge

was started, and by 1430 it had been finished. A tank crossing was ready before

dark. The same day two squads of the Reconnaissance Company crossed the lower

Asato and roamed the streets of northwestern Naha without meeting resistance.

- [373]

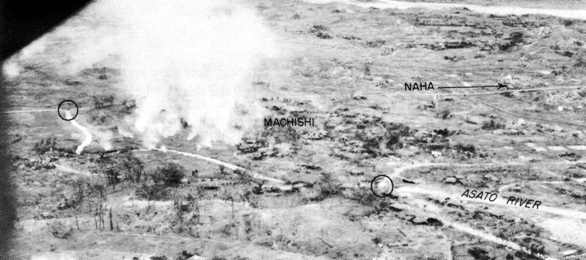

- CROSSING THE ASATO RIVER, marines laid smoke to

cover their advantage at Machishi 23 May. Destroyed bridges (circled)

had not been replaced at time picture was made. Eastern Naha and Kokuba

estuary are at upper right.

-

- ENTERING NAHA, Marine patrols move through deserted streets in the

western part of town. the walled compounds around the houses, typical

of Oriental urban structures, gave good cover for snipers.

-

- [374]

- The Occupation of Naha

- The unmolested patrols into Naha on

24 May led to the crossing of the lower Asato on 25 May by the Reconnaissance

Company of the 6th Marine Division, which during the day penetrated deep into

Naha west of the northsouth canal that bisects the city. Only an occasional

Japanese straggler was met; sniper fire was almost nonexistent. A few Okinawan

civilians who were still hiding in the rubble of the city said they had seen

only scattered 5- or 6-man Japanese patrols during the past week.7

The rubble of Naha was deserted. The Reconnaissance Company dug in without

packs and gear to hold the gain so easily obtained.

-

- Naha had no tactical value other than

to afford the Americans a route of travel southward to the next objective.

The city was located in a wide coastal flat at the mouth of the Kokuba River;

it was dominated by the high ground of the Oroku Peninsula across the channel

to the south, and by a ridge that curved around the city and coastal flat

from the northeast to southwest along the Kokuba estuary.

-

- On 27 May one company of the 2d Battalion,

22d Marines, crossed the Asato, passed through the lines of the Reconnaissance

Company, and pressed deeper into the western part of Naha. The next morning

at daylight the marines moved on toward the Kokuba estuary; reaching it at

0900, they received hardly a shot as they picked their way among the demolished

buildings and the heaps of debris. The effort of a platoon to press forward

to scout the situation at the approaches to Ona-Yama Island, which lies in

the middle of the Kokuba Channel opposite the south end of the Naha Canal,

failed. The marines were met by heavy machine-gun fire, and in their withdrawal

the platoon leader was killed. All of Naha west of the canal and north of

Kokuba was now in possession of the marines. Steps were taken quickly to defend

this portion of the city. Eight 37-mm. antitank guns were ranged along the

sea wall bordering the north bank of the Kokuba estuary, and a line of marines

took up positions behind the sea wall. The 1st Armored Amphibious Battalion

held and patrolled the seaward side of the city.

-

- During the night of 28 May engineers

put three footbridges across the canal, and before dawn the 1st Battalion,

22d Marines, crossed to Telegraph Hill in east Naha, where a fight raged throughout

the day without noticeable gains. On 30 May the 2d and 3d Battalions, 22d

Marines, crossed the canal,

- [375]

- passed through the 1st Battalion,

and took up the assault. Enemy machine guns emplaced in burial tombs on Hill

27 in east Naha temporarily checked the infantry. During most of the day

tanks were unable to reach the position, but in the afternoon three worked

their way along the road north of the hill, and their direct fire enabled

the marines to seize it.

-

- The Kokuba Hills

- The Kokuba Hills extend eastward from

the edge of Naha along the north side of the Kokuba estuary and the Naha-Yonabaru

valley. They guard the southern and southwestern approaches to the rear of

Shuri. With the 6th Marine Division pressing south along the west coast, defense

of this terrain was vital to the enemy in preventing an envelopment of Shuri

from Naha. On the night of 22-23 May the headquarters of the Japanese

44th Independent Mixed Brigade moved from Shuri to Shichina village, in

the Kokuba Hills, for better control of the operations on this flank 8

The Japanese upon evacuating Naha took positions in the high ground in the

eastern part of the city and the semicircle of hills beyond. There the fight

on the enemy's left flank entered its next phase.

-

- Since the crossing of the upper Asato

on 23 May, the left (east) elements of the 6th Marine Division had encountered

continuing opposition. The 4th Marines held this part of the line, and suffered

heavy casualties as it tried to press forward in the mud of the flooded valley

and low clay hills. By the night of 25 May Company E had been reduced to forty

enlisted men and one officer. That day the 1st Battalion took the village

of Machishi, but with bridges washed out and the torrential rains making the

terrain impassable for tanks it was learned that infantry could go ahead only

with heavy casualties. On 28 May the 29th Marines relieved the 4th Marines,

and, although opposed by enemy smallarms fire, by the close of the day it

had pressed to within 800 yards of the Kokuba River.

-

- Both the 22d and the 29th Marines

were now attacking east against the hill mass centering on Hill 4.6, west

of Shichina village and north of the Kokuba estuary. After the fall of Hill

27 on 30 May there was a rapid advance of several hundred yards until the

defenses of Hill 46 were reached. Then another intensive battle was fought

in the rain and mud. Fourteen tanks clawed their way into firing position

on the last day of the month and put direct fire into the enemy. Even then

intense machine-gun and mortar fire denied the hill to a strong

- [376]

- coordinated attack, although large

gains were made. Throughout the night American artillery pounded Hill 46.

The next morning, on 1 June, the assault regiments took the hill, broke through

the Shichina area, and then seized Hill 98 and the line of the north fork

of the Kokuba.

-

-

- When elements of the 96th Division

seized the east face of Conical Hill and of Sugar Hill at the southern end

of the Conical hogback, a path was cleared for the execution of a flanking

maneuver around the right end of the Japanese line. The flanking force, once

through the corridor and past Yonabaru, could sweep to the west up the Yonabaru

valley and encircle Shuri from the rear. The main force of the Japanese army

would then be trapped. This was the plan which the XXIV Corps was ready to

put into effect when night fell on 21 May.9

-

- Funneling Through the Conical Corridor

- Strengthened by 1,691 replacements

and 546 men returned to duty from hospitals since it left the lines on 9 May,

the 7th Division moved up to forward assembly areas just north of Conical

Hill and prepared to make the dash through the corridor. At 1900 on 21 May

the 184th Infantry, chosen by General Arnold to lead the way, was in place

at Gaja Ridge, at the northern base of Conical. The initial move of the envelopment

was to be made in the dead of the night and in stealth.10

General Buckner felt that "if the 7th can swing round, running the gauntlet,

it may be the kill."11

-

- Rain began to fall an hour before

Company G, 184th Infantry, the lead element, was scheduled to leave its assembly

area. The rain increased rapidly until it was a steady downpour. Up to 0200

on 22 May, the hour of departure, the men huddled under their ponchos listening

to the dull, heavy reverberations of the artillery preparation, which sounded

even louder and nearer in the rain. Then, in single column, the company headed

south through the black night, the

- [377]

- rain, and the sludge. No one fired

as two Japanese dodged into the shadows and the debris of Yonabaru, and at

0415 the company formed at a crossroads in the ruined town, platoons abreast,

ready to push on to Spruce Hill. It accomplished this advance without incident.

Once on the crest of Spruce Hill, Company G sent up a flare signaling Company

F to come through and try to reach Chestnut Hill.

-

- Daylight, a dull and murky gray, had

come when Company F reached the crest of Chestnut, 435 feet above the coast

1,000 yards southeast of Yonabaru. Only one man was wounded in this phase

of the assault. As Company F reached the crest of Chestnut and looked down

over the southern slope, several enemy soldiers were spotted climbing the

hill, apparently to take up defense positions. A soldier said as he looked

at them that they "had better hold reveille a little earlier." Complete

surprise had crowned the American effort. It was learned later that the Japanese

command had not expected the Americans to make a night attack or to attack

at all when tank and heavy-weapons support were immobilized by rain and mud.12

-

- The 3d Battalion followed the 2d through

Yonabaru. It then began advancing to the south toward juniper and Bamboo Hills

on a line southwest of Chestnut, the other high ground which the 184th was

to seize before it would be considered safe for the 32d Infantry to come through

the corridor and turn west to cut behind Shuri. The attack continued on the

rainy morning of 23 May, with the 2d and 3d Battalions pressing forward to

these initial objectives. At the end of the day, except for a small gap between

Company G on Juniper Hill and Company L on Bamboo Hill, the 184th Infantry

had won a solid line stretching from the seacoast across the southern slope

of Chestnut Hill and then across to juniper and Bamboo. In two rainy days

the 184th had forced a 2,000-yard crack in the enemy's defenses south of Yonabaru

and accomplished its mission. Now the 32d Infantry could begin the second

and decisive phase of the enveloping plan.

-

- The 32d Infantry Attempts an Envelopment

- While the 184th Infantry held the

blocking line from Chestnut to Bamboo and thus protected the left flank and

rear, the 32d Infantry was to drive directly west along the Naha-Yonabaru

valley to cut off Shuri from the south. The success of the entire plan of

encirclement depended upon the 32d Infantry's carrying out its part.

- [378]

- On 22 May, while the 184th Infantry

was pressing south, Company F of the 32d Infantry moved to the southern tip

of Conical Hill, just west of Yonabaru, to help protect the right side of

the passage. The main body of the 32d Infantry, however, did not start moving

until the morning of 23 May, after Colonel Green of the 284th Infantry radioed

that his attack was going well and that it would be safe for the 32d to proceed.

At 1045 on 23 May the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry, passed through Yonabaru

and headed west. Its initial objective was the string of hills west of Yonabaru

and south of the Naha-Yonabaru road, centering on Oak Hill just below the

village of Yonawa. By nightfall two battalions, the 2d and 3d, were deployed

a mile southwest of Yonabaru facing west, ready to make their bid for envelopment.

Already heavy machine-gun fire had slowed the advance and served notice that

the enemy would bitterly oppose a drive up the Yonabaru valley. The continuing

rains had by this time mired the tanks in their assembly areas north of Conical

Hill, and the armor which commanders had counted on to spearhead the drive

to the west was unable to function. Heavy assault guns likewise were immobilized.

The infantry was on its own.13

-

- During 24 May the 32d Infantry developed

the line where the Japanese meant to check the westward thrust of the 7th

Division. This line ran south from Mouse Hill (southwest of Conical Hill),

crossed the Naha-Yonabaru road about a mile west of Yonabaru, and then bent

slightly southwest to take in June and Mabel Hills, the latter being the key

to the position. Mabel Hill guarded the important road center of Chan, which

lay two miles almost directly south of Shuri. Oak Hill, an enemy strong point,

was somewhat in front of this line. Tactically, it was apparent that this

line protected the Shuri-ChanKaradera-Kamizato-Iwa road net, the easternmost

of two routes of withdrawal south from Shuri.

-

- The Japanese reacted slowly to the

initial penetration below Yonabaru. Mortar and artillery fire, however, gradually

increased. The scattered groups of second-class troops encountered plainly

did not have the skill and determination of the soldiers manning the Shuri

line. On 23 May elements of the Japanese 24th Division were dispatched

from Shuri to retake Yonabaru.14

This effort took shape in numerous counterattacks on the night of 24-25 May

against the 184th Infantry, which had just secured a lodgment on Locust Hill,

a high,

- [379]

- EAST COAST CORRIDOR, looking north along Highway 13 from Yonabaru.

Conical Hill is just to left of Gaja.

-

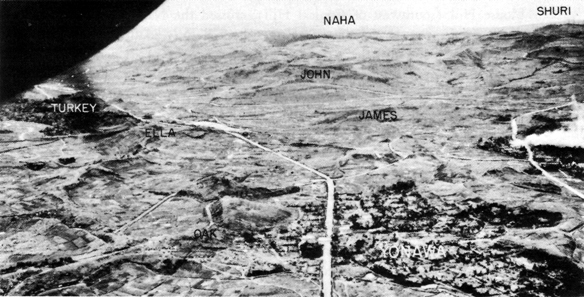

- YONABARU-NAHA VALLEY highway, with Yonawa and Oak Hill in foreground.

Picture was taken 26 May as 7th Division infantrymen pressed back the

enemy's right flank below Shuri.

-

- [380]

- broad coral escarpment half a mile

south of Chestnut Hill. At 0230 the Japanese counterattack also struck elements

of the 32d Infantry west of Yonabaru. The enemy made some penetration of American

lines at this point, and fighting continued until after dawn, when the Japanese

assault force withdrew, leaving many dead behind.15

-

- On 25 or 26 May, the main body of

the enfeebled 62d Division left Shuri and made a circuitous march to the southeast

to join the fight against the 184th Infantry below Yonabaru 16

Its arrival on the Ozato-Mura front had no important effect except to strengthen

the covering and holding force. The HemlockLocust Hill Escarpment area was

cleared of the enemy on 26 May, and thereafter the 184th Infantry met no

serious opposition as it pressed south to the vicinity of Karadera 17

Patrols sent deep to the south reported encountering only scattered enemy

troops. It became increasingly evident that the Japanese had pulled back their

right flank, were fighting only a holding action there, and had no intention

of withdrawing into the Chinen Peninsula as had been thought possible by American

commanders.

-

- It was on the right end of the 7th

Division's enveloping attack that the Japanese brought the most fire power

to bear and offered the most active resistance. The high ground at this point,

where the southwest spurs of Conical Hill came down to the Naha-Yonabaru valley,

was integrated with the Shuri fortified defense zone. American success at

this point would cut the road connections south from Shuri and permit its

envelopment; hence the Japanese denied to the 96th Division any gains in this

area which would have helped the 32d Infantry in its push west.

-

- The Japanese Hold

- The bright promise of enveloping Shuri

faded rapidly as the fighting of 23-26 May brought the 32d Infantry practically

to a standstill in front of the Japanese defense line across the Yonabaru

valley. The Japanese had emplaced a large number of antitank guns and automatic

weapons which swept all approach routes to the key hills. Mortars were concentrated

on the reverse slopes. Had tanks been able to operate, the 32d Infantry could

perhaps have destroyed the enemy's fire power and overrun the Japanese defenders,

but the tanks were mired. On 26 May torrential downpours totaled 3.5 inches

of rain; the last ten

- [381]

- days of May averaged 1.11 inches daily.18

General Hodge stated later that no phase of the Okinawa campaign worried him

more than this period when the 32d Infantry was trying to break through behind

Shuri.19

-

- Decisive action in the Japanese holding

battle took place in the vicinity of Duck and Mabel Hills, east of Chan. Here,

on 26 May, the 32d Infantry tried to break the enemy resistance, but in a

fierce encounter on Duck Hill it was thrown back with heavy casualties. The

fighting was so intense and confused that five Japanese broke through and

attacked T/5 William Goodman, the only medic left in Company I, who was bandaging

wounded men in a forward exposed area. Goodman killed all five Japanese with

a pistol and then held his ground until the wounded were evacuated. In the

withdrawal from Duck Hill the dead had to be left behind. No gain was made

on the 27th, and on the 28th there was no activity other than patrolling.20

-

- The most significant gains of the

32d Infantry in its drive west were to come on 30 and 31; May, when all three

of its battalions launched a coordinated attack. By the end of 30 May the

32d had taken Oak, Ella, and June Hills; the advance brought the regiment

directly up against Mabel and Hetty Hills and the defenses of Chan. On the

last day of the month the 32d Infantry seized Duck Hill, consolidated positions

on Turkey Hill, north of Mabel, and occupied the forward face of Mabel itself.

The enemy still held the reverse slope of Mabel and occupied the town of Chan.

The Japanese encountered were not numerous, but they had to be killed in place.

They were the rear-guard holding force.

-

- In front of the 184th Infantry to

the southeast, the enemy fought a delaying action on 28-29 May at Hill 69,

commonly called Karadera Hill, just north of the village of the same name.

When patrols of the 184th Infantry penetrated deep into the Chinen Peninsula

on 30 May without encountering the enemy, it was obvious that this rugged

region would not become a battlefield.21

-

- By 30 May the XXIV Corps lines showed

a large and deep bulge on the left flank below the Naha-Yonabaru road; here

the American lines were approximately two miles farther south than at any

other part of the cross-island battlefront. On the American left flank the

envelopment of Shuri had almost succeeded in catching the Japanese army.

- [382]

page created 10 December 2001