- Chapter XV:

-

- The Fall of Shuri

-

- As the end of May approached, conflict

had been raging on the Shuri line nearly two months and many an American soldier

wondered whether Shuri would ever be taken or whether he would be alive to

witness its capture. While on 21 May the eastern slope of Conical Hill had

been taken, after more than a week of further fighting the high belt of Shuri

defenses still held firm all around the ancient capital of the Ryukyus. The

American gains in southern Okinawa had been confined to a rather small area

of hills and coral ridges which, aside from Yontan and Kadena airfields seized

on 1 April, had no important value for the attack on the Japanese home islands.

It is true that these airfields, the flat extent of Ie Shima, and certain

coastal areas of central Okinawa suitable for air base development were already

swarming with naval and army construction battalions, at work on the task

of making the island over into a gigantic, unsinkable carrier from which to

mount the final air assault on Japan. But this was just a beginning. Most

of the big prizes-the port of Naha, the big anchorage of Nakagusuku Bay, Yonabaru,

Shuri, Naha airfield, and the flat coastal ground of southern Okinawa-were

still effectively denied to the Americans, long after they had expected to

capture them.

-

- By the end of May, however, the flower

of General Ushijima's forces on Okinawa had been destroyed. The three major

enemy combat units-the 62d Division, the 24th Division, and

the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade-had all been committed to the line

and had all wasted away as a result of the incessant naval gunfire, artillery

fire, air attacks, and the tank and infantry combat. Second-rate troops had

for some time been present in the line, mixed with the surviving veterans

of the regular combat units. By the end of May 62,548 of the enemy had been

reported killed "and counted" and another 9,529 estimated as killed.

As compared with 3,214 killed in northern Okinawa and 4,856 on le Shima, 64,000

of these were reported killed in the fighting in the Shuri fortified zone.

According to division reports, about 12,000 were killed by the 1st and 6th

Marine Divisions and 41,000 by the 7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th Army Divisions

while in the line at one time or another under XXIV Corps. The

- [383]

- largest number were killed by the

96th Division, credited with 17,000.1

Even though these reports of enemy losses are undoubtedly somewhat exaggerated,

there is no question that Japanese forces, especially infantry combat units,

had been seriously depleted. A conservative estimate would indicate that 50,000

of the best Japanese troops had been killed in the Shuri fighting by the end

of May. The enemy's artillery also was weakening noticeably as piece after

piece was captured or was destroyed by naval gunfire, counterbattery fire,

and air bombing.

-

- Nothing illustrates so well the great

difference between the fighting in the Pacific and that in Europe as the small

number of military prisoners taken on Okinawa. At the end of May the III Amphibious

Corps had captured only 128 Japanese soldiers. At the same time, after two

months of fighting in southern Okinawa, the four divisions of the XXIV Corps

had taken only 90 military prisoners. The 77th Division, which had been in

the center of the line from the last days of April through May, had taken

only 9 during all that time 2

Most of the enemy taken prisoner either were badly wounded or were unconscious;

they could not prevent capture or commit suicide before falling into American

hands.

-

- In the light of these prisoner figures

there is no question as to the state of Japanese morale. The Japanese soldier

fought until he was killed. There was only one kind of Japanese casualty-the

dead. Those that were wounded either died of their wounds or returned to the

front lines to be killed. The Japanese soldier gave his all.

-

- Casualties on the American side were

the heaviest of the Pacific war. At the end of May, losses of the two Marine

divisions, whose fighting included approximately a month on the Shuri front,

stood at 1,718 killed, 8,852 wounded, and 101 missing. In two months of fighting,

chiefly on the Shuri front, the XXIV Corps suffered 2,871 killed, 12,319 wounded,

and 183 missing. The XXIV Corps and the III Amphibious Corps had lost a total

of 26,044 killed, wounded, or missing. American losses were approximately

one man killed to every ten Japanese.3

-

- Nonbattle casualties were numerous,

a large percentage of them being neuropsychiatric or "combat fatigue"

cases. The two Marine divisions had had 6,315 nonbattle cases by the end of

May; the four Army divisions, 7,762. The most

- [384]

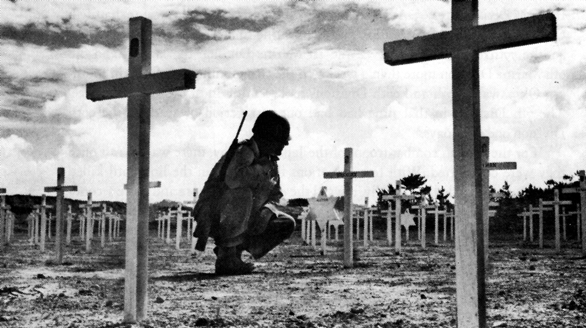

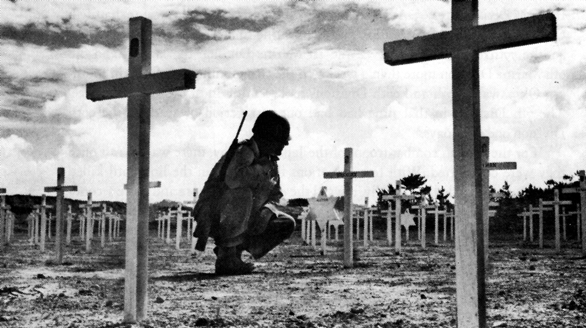

- "There was only one kind of Japanese casualty..."

-

- Our Losses: "one man killed to every ten Japanese."

-

- CASUALTIES

-

- [385]

- important cause of this was unquestionably

the great amount of enemy artillery and mortar fire, the heaviest concentrations

experienced in the Pacific war. Another cause of men's nerves giving way was

the unending close-in battle with a fanatical foe. The rate of psychiatric

cases was probably higher on Okinawa than in any previous operation in the

Pacific.4

-

- If Japanese artillery and mortar fire

shattered nerves to such an extent among American troops, some idea may be

gained of the ordeal experienced by the Japanese when they were exposed to

the greatly superior American fire power delivered by artillery, naval gunfire,

and planes. The Japanese, however, were generally deep underground during

heavy bombardment; the Americans were usually in shallow foxholes, in defilade,

or exposed on the slope or crest of some ridge that was under attack.

-

- The fighting strength of the American

combat units engaged in southern Okinawa at the end of May stood at 45,980

for the III Amphibious Corps and 51,745 for the XXIV Army Corps. The infantry

divisions, especially those of the Army, were considerably below strength.

On 26 May the 77th Infantry Division had a strength, exclusive of attached

units, of only 9,628 enlisted men; the 96th Infantry Division, 10,993. At

the end of May the American troops were exhausted. Out of 61 days the 96th

Division had been in the line 50 days, the 7th Division 49, the 77th Division

the last 32, the 1st Marine Division the last 31, and the 6th Marine Division

more than 3 weeks. In the two months of fighting in southern Okinawa the 7th

and 96th Divisions had seen the most continuous service. The 7th Division

in that time had had one rest period of 12 days, the 96th Division one of

11 days.5

-

- For the veteran combat troops of the

Japanese army, there was no rest once they were committed. With few exceptions

they stayed in the line until killed or seriously wounded. Gradually, toward

the end of May, more and more second rate troops from service units and labor

groups were fed into the Japanese line to bolster the thinning ranks of the

combat infantry.

-

- American armor, which played so important

a part in the ground action, had suffered heavily. By the end of May, not

counting Marine tank losses, there had been 221 tank casualties in the four

Army tank battalions and the one

- [386]

- armored flame thrower battalion. Of

this total, 94 tanks, or 43 percent, had been completely destroyed. Enemy

mines had destroyed or damaged 64 tanks and enemy gunfire 111. Such mishaps

as thrown tracks or bogging down in bad terrain had accounted for 38, of which

25 were subsequently destroyed or damaged, mostly by enemy action. The 221

tank casualties constituted about 57 percent of the total number of Army tanks

on Okinawa. At least 12 of the valuable and irreplaceable armored flame-throwing

tanks were among those lost.6

-

-

- American staff officers believed that

the Japanese would fight at Shuri to the end. The struggle had gone on so

long in front of Shuri that everyone apparently had formed the opinion that

it would continue there until the last of the Japanese defenders had been

killed. In a staff meeting at Tenth Army on 19 May Col. Louis B. Ely, intelligence

officer of the Tenth Army, said that it looked as though the Japanese would

fight at Shuri to the death. In another staff meeting, on the evening of 22

May, Colonel Ely, in commenting on the passage of the 7th Division down the

Conical corridor, noted the absence of strong resistance to the move and interpreted

this as supporting the view that the "Japs will hole up in Shuri."

At the same time General Buckner remarked: "I think all Jap first line

troops are in the Shuri position. They don't appear to be falling back."

On 25 May the Tenth Army periodic intelligence report stated that "evidence

of captured documents, POW [Prisoners of War] statements, and air photographs

tends to indicate that the enemy intends to defend the Shuri area to the last."

7

-

- Actually, the Japanese had for some

time been preparing to evacuate Shuri. About 20 May, even before the final

stretches of the eastern face of the Conical hogback fell to the 96th Division,

the pressure on both flanks and the American gains in front of Shuri forced

the Japanese command to realize that a decision must be made whether to fight

to the end at Shuri, bringing all remaining resources to that area, or to

withdraw from Shuri to other positions farther south. The loss of ground on

the west flank in the vicinity of Sugar Loaf Hill

- [387]

- and Naha was not, indeed, considered

by the Japanese as endangering too greatly the defense of Shuri, as they believed

that they could meet this threat by withdrawing the flank to positions south

and southeast of Naha. But the loss of the remaining positions on the east

and south of Conical Hill made the defense of Shuri extremely difficult and

tipped the scales. 8

-

- Decision Under Shuri Castle

- On 21 May, the very day when the 96th

Division completed the seizure of the eastern face of Conical and carved out

the corridor to the south, General Ushijima called a night conference in the

command caves under Shuri Castle. It was attended by all division and brigade

commanders of the Japanese 32d Army. Three alternative courses of action

were proposed: a final stand at Shuri; withdrawal to the Chinen Peninsula;

and withdrawal to the south 9

-

- The first plan was favored by the

62d Division, which had fought so long in the Shuri area and looked

upon that part of the island defenses as peculiarly its own. The argument

of General Fujioka, the division's commander, was supported by the presence

of large stores at Shuri and the general feeling that a withdrawal would not

be in the best traditions of the Japanese Army. The second proposal, to retreat

to the Chinen Peninsula, received little support from anyone; it was considered

unfeasible because of the difficulties of transportation over mountainous

terrain and poor roads. The third possibility, that of withdrawing to the

south, had in its favor the prospect of prolonging the battle and thereby

gaining time and exacting greater attrition from the American forces. Other

considerations favoring the plan were the presence in the south of positions

prepared earlier by the 24th Division and the availability there of

considerable quantities of stores and supplies.

-

- For a time the trend of the discussion

favored a final battle at Shuri, but it was generally conceded that this would

result in a quicker defeat for the Japanese Army. The prospect of prolonging

the battle by a withdrawal to the south was the determining consideration

in the staff debate, and the decision was finally made to order a retreat

to the south. The commanders present were directed to prepare for withdrawal

from Shuri at the end of the month. The transport of supplies and wounded

began the following night, 22-23 May. This final tactical deployment began

silently, unsuspected by the Americans.

- [388]

- Discovery From the Air

- From 22 May until the end of the month

aerial observation over the enemy's rear areas was limited by the almost constant

overcast and the hard rains. Planes, however, were over the enemy's lines

for short periods nearly every day, and on 22 May groups of individuals, believed

to be civilians, were observed moving south at dusk from Kamizato. The movement

continued the following day. It was not believed that these people were soldiers

since they were wearing white cloth. Leaflets had previously been dropped

behind the Japanese lines telling the Okinawan civilians to identify themselves

by wearing white and thus avoid being strafed and bombed. On 24 and 25 May

aerial observation noted continued movement southward, but the impression

persisted that it was civilian.10

-

- The first doubt of the correctness

of this view came on 26 May. In the afternoon the overcast lifted long enough

for extensive aerial observation over the south end of the island. Movement

extending from the front lines to the southern tip of the island was spotted.

About 2,000 troops were estimated to be on the move between Oroku Peninsula

and the middle part of the island below the Naha-Yonabaru valley. At 1800

from 3,000 to 4,000 people were seen traveling south just below Shuri. About

a hundred trucks were on the roads in front of the Yaeju-Dake. At noon two

tanks were observed pulling artillery pieces, and an hour later a prime mover

towing another artillery piece was spotted. During the afternoon seven more

tanks, moving south and southwest, were seen.

-

- Pilots strafed the moving columns

and reported that some of the soldiers seemed to explode when the tracers

hit them-an indication that they probably were carrying satchel charges. Artillery

and naval gunfire, guided by spotter planes, hit the larger concentrations

of movement and traffic with destructive effect. Naval gunfire alone was estimated

to have killed 500 Japanese in villages south of Tsukasan, and to have destroyed

1 artillery piece and 5 tanks.11

-

- Just before dark, at 1902, a column

of Japanese with its head near Ozato, just west of the Yuza-Dake, was seen

in the far south of the island, moving north. Fifteen minutes later it was

reported that this road was blocked to a point just above Makabe with troops

moving north. The troop column extended over about 5,000 yards of road and

was estimated to be in regimental strength.

- [389]

-

- SECRET RETREAT of the Japanese from Shuri was difficult

for Intelligence to discover because of pitted, wooded terrain such as

this. Where, however, enemy could be found, they were scattered or destroyed.

These Japanese howitzers (below) were caught on road leading south from

Shuri.

-

-

- [390]

- This was the largest enemy troop movement

ever seen in the Okinawa campaign.12

-

- The reports of the aerial observers

on the 26th were perplexing. Enemy troops were moving in all directions. The

majority, however, were headed south; the main exception was the largest column,

which was moving north. The heaviest movement was in an area about five miles

south of Shuri. It was noted that artillery and armor were moving south. What

did it all mean? One careful appraisal concluded that the Japanese were taking

advantage of the bad weather, poor aerial observation, and the general stalling

of the American attack to carry out a relief of tired troops in the lines

by fresh reserves from the south. It was believed that artillery was being

moved to new emplacements for greater protection and for continued support

of the Shuri battle.13

-

- The next day, 27 May, little movement

was noted behind the enemy's lines in the morning, but in the afternoon from

2,000 to 3,000 troops were seen moving in both directions at the southern

end of the island.14

-

- After the reports of enemy movement

on 26 May by aerial observers, General Buckner issued on 27 May an order directing

that both corps "initiate without delay strong and unrelenting pressure

to ascertain probable intentions and keep him [the Japanese] off balance.

Enemy must not be permitted to establish himself securely on new positions

with only nominal interference." 15

In view of the preponderance of other evidence it seems that this order was

purely precautionary, and that there was no real conviction in the American

command that the Japanese were actually engaged in a withdrawal from Shuri.

-

- On 28 May the Tenth Army intelligence

officer observed in a staff meeting that it "now looks as though the

Japanese thinks holding the line around north of Shuri is his best bet . .

. . It is probable that we will gradually surround the Shuri position."16

General Buckner indicated at this meeting that he was concerned about the

possibility of a Japanese counterattack against the 7th Division on the left

flank. He asked, "What has Arnold in reserve against counterattack?"

17

On the following day, however, General Buckner said it looked as

- [391]

- though the Japanese were trying to

pull south but that they had made the decision too late.18

On the day before, a total of 112 trucks and vehicles and approximately 1,000

enemy troops had been observed on the move to the south and southeast, in

the vicinity of Itoman on the west coast, and around Iwa and Tomui in front

of the Yaeju-Dake, a strong terrain position in the south.19

On 28 May Marine patrols found evidence of recently evacuated enemy positions

west of Shuri 20

On 29 May there was almost no aerial observation because of a zero ceiling,

and on 30 May practically no movement was seen behind the enemy's lines.

-

- American opinion on the meaning of

the Japanese movements crystallized on 30 May. After a meeting with III Amphibious

Corps and XXIV Army Corps intelligence officers the Tenth Army intelligence

officer reported at a staff meeting on the evening of 30 May that they had

reached a consensus that the "enemy was holding the Shuri lines with

a shell, and that the bulk of the troops were elsewhere." He estimated

that there were 5,000 enemy troops in what he hoped would be the Shuri pocket,

and stated that he did not know where the bulk of the Japanese troops were.21

At a staff meeting held on the evening of 31 May, it was suggested that the

enemy would make his next line the high ground from Naha-Ko and the Oroku

Peninsula on the west to Baten-Ko below Yonabaru on the east. At this meeting

General Buckner stated that "he [General Ushijima] made his decision

to withdraw from Shuri two days too late." 22

During the following days it became clear that the Americans had underestimated

the scope of the enemy's tactical plan and the extent to which it had been

executed.

-

- The Retreat South

- Once the Japanese decision to withdraw

had been made, steps were taken to carry out the withdrawal in an orderly

manner. The major part of the transportation fell to the 24th Transport

Regiment of the 24th Division. This unit had been exceptionally

well trained in night driving in Manchuria, and as a result of its fine performance

in the withdrawal from Shuri it received a unit citation from the 32d

Army. When the withdrawal from Shuri began only 80 of the 150 trucks of

the transport regiment were left. One hundred and fifty Okinawan

- [392]

- Boeitai helped to load the vehicles.

The formal order from 32d Army headquarters to withdraw from Shuri

was apparently issued on 24 May.23

-

- The movement of supplies and the wounded

began first, one truck unit moving out the night of 22 May. Communication

units proceeded between 22 and 28 May to Mabuni and Hill 89, where the

32d Army proposed to establish its new command post. The 36th Signal

Regiment left Shuri on 26 May and arrived at Mabuni by way of Tsukasan

on 28 May. Other units moved out early. The 22d Independent Antitank Gun

Battalion left the Shuri area on the night of 24.-25 May, withdrawing

to the Naha-Yonabaru valley area, and at the end of the month continued on

south to the southern end of the island. Remnants of the 27th Tank Regiment

began to withdraw from Shuri on 26 May, passing through Kamizato. At the same

time the 103th and 105th Machine Cannon Battalions left the

Shuri and Shichina areas and began the movement south, hand-carrying some

of their guns.24

-

- Of the major combat units of the

32d Army, the 62d Division left first. It began moving out of

Shuri on 26 May, two days ahead of the original schedule, fighting delaying

actions in the zone of the 7th Division, where the bulge had been pushed deep

to the southwest of Yonabaru. The 44th Independent Mixed Brigade on

the left flank in front of the 6th and 1st Marine Divisions was to begin withdrawing

from the front lines on 26 May, but, because of the failure of naval ground

troops to arrive and take over the lines, the evacuation of the front positions

by the brigade had to be delayed two days, and it was not until 28 May that

the withdrawal began in the western part of the line. The units of the brigade

assembled behind the lines and made the move south in mass on the night of

1-2 June. One battalion, the 3d, withdrew directly from Shuri. The 24th

Division remained behind longest. Elements of the division fought in front

of Shuri as late as 30 May, and the division headquarters itself did not leave

Shuri until 29 May. The mortar battalions supporting the Shuri front had for

the most part already left, their main movement south having taken place between

27 and 29 May.25

- [393]

- The evidence is conflicting concerning

the date when the 32d Army headquarters left Shuri. The cook for the

32d Army staff said that the Army headquarters left Shuri

on 26 May and arrived at the Hill 89 headquarters cave near Mabuni on 29 May.

Officers of the 62d Division confirmed this, stating that the

Army headquarters left Shuri on 26 May, the same day the division itself

started to move south. On the other hand, Colonel Yahara, 32d Army

operations officer, and Mr. Shimada, secretary to General Cho, stated that

the Army headquarters did not move from Shuri until the night of 29 May. On

the whole the evidence seems to indicate that the Army headquarters

moved from Shuri before 29 May. On that day elements of the 1st Marine Division

entered Shuri Castle, the 24th Division headquarters left Shuri, and

only the last of the rearguard units were still in the line as a holding force.

It seems improbable that the 32d Army headquarters would have remained

behind so long. It appears likely that the Army headquarters left Shuri at

night between 26 and 28 May, possibly as early as 26 May.26

-

- The main movement of 32d Army

combat units out of the inner Shuri defense zone took place from 26 to 28

May, some of the units, particularly the 62d Division, fighting as

they went. The 3d Independent Antitank Battalion, the 2d Battalion

of the 22d Regiment of the 24th Division, and part of the

17th Independent Machine Gun Battalion formed the principal components

of the final holding force in front of Shuri, 29-31 May, after the 32d

Regiment withdrew.27

-

-

- As the battle lines tightened around

Shuri at the end of May, the 1st Marine Division on the northwest and the

77th Division on the north and northeast stood closest to the town. Patrols

reported no signs of weakness in the enemy's determination to hold the Shuri

position. Invariably they drew heavy fire when they tried to move forward.

There was one exception to the reports of the patrols. On 28 May a patrol

brought back to the 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division, the news that Shuri

Ridge, the high ground south of Wana Draw, seemed to be held more lightly

than formerly. (See Map No. XLIV. )

- [394]

- SHURI HEIGHTS, at southwest corner of the city, was approached by

the marines from the low ground at right. First building to be taken was

the Shuri Normal School (upper left). (Photo taken 28 April 1945.)

-

- [395]

- The Marines Take Shuri Castle

- At 0730 on 29 May the 1st Battalion,

5th Marines, left its lines and started forward toward Shuri Ridge, where

patrol action the previous day had indicated a possible weakness in the enemy's

lines. The high ground was quickly occupied. The 1st Battalion was now on

the ridge that lay at the eastern edge of Shuri. Shuri Castle itself lay from

700 to 800 yards almost straight west across the Corps and division boundary.

From all appearances, this part of the Shuri perimeter was undefended and

the castle could be captured by merely walking up to it. The battalion commander

immediately requested permission from his regimental commander to cross the

Corps boundary and go into Shuri Castle. The request was approved, and at

midmorn Company A of the 5th Marines started toward the spot that had been

so long a symbol of Japanese strength on Okinawa. At 1015 Shuri Castle was

occupied by Company A.28

The Marine unit entered Shuri through a gap in the covering forces caused

by the withdrawal of the 3d Battalion, 15th Independent Mixed

Regiment of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade, in the course

of the Japanese retreat from Shuri.29

This seems to have been the only notable instance of confusion and mistake

in the Japanese withdrawal operation as a whole. Everywhere else around Shuri

the Japanese still held their covering positions in the front lines.

-

- As a result of the unexpected entrance

into Shuri, the 1st Marine Division at 0930 ordered the 1st Marines to bypass

Wana Draw, leaving its position in the line next to the 77th Division, and

to move around to the southwest to relieve the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines,

in Shuri. This move was carried out with the 3d Battalion leading and the

1st Battalion following. Enemy positions were bypassed on the right, and by

night the two battalions had established a perimeter in the south of Shuri.

-

- The elements of the 1st Marine Division

which entered Shuri Castle had crossed over into the 77th Division zone of

action and line of fire without giving that unit notice that such a movement

was under way. The 77th Division learned of the move barely in time to cancel

an air strike on the Shuri Castle area which it had scheduled.30

-

- The next day, the Marine units at

Shuri Castle and south of Shuri did not move, except for small patrols that

were turned back by heavy machine-gun

- [396]

- and 47-mm. antitank fire a few hundred

yards north of the castle. Vehicles could not reach the marines in Shuri and

their supplies were critically low. Carrying parties of replacement troops

formed an almost unbroken line from the west coast dumps all the way to Shuri.

Many men collapsed from sheer exhaustion. Five air drops through heavy clouds

to the marines in Shuri relieved somewhat their critical supply situation

on 30 May.31

-

- The entrances to the caves under Shuri

Castle were still held by the enemy at 1330 on 30 May, and no additional ground

had been taken in Shuri itself.32

The two Marine battalions, dug in, merely formed a pocket within the Japanese

perimeter on which the enemy's rear guard was fighting the holding battle

around Shuri. The occupation of Shuri Castle did not cause these Japanese

to withdraw from their covering positions or result in the occupation of Shuri

itself; nor did it, so far as is known, affect the enemy's plans. The marines

themselves had all they could do to get food and water and some ammunition

up to their position in order to stay.

-

- The Crust Breaks

- Although the holding party at 100

Meter Hill repulsed the 306th Infantry on 30 May when it attacked across the

Marine line, elsewhere across the Shuri front key positions were wrested from

the enemy in what obviously was a breaking up of the Japanese rear-guard action.

Now for the first time there was convincing proof along the front lines that

the Japanese had withdrawn from Shuri. (See Map No. xLV.)

-

- Dorothy Hill, a fortress directly

east of Shuri and a tower of strength in the enemy's inner line for the past

two weeks, was attacked by the 3d Battalion, 307th Infantry, 77th Division.

The first platoon to reach the base of the hill was pinned down by heavy fire,

the platoon leader and all noncommissioned officers being wounded. Other platoons

maneuvered into position and finally one squad reached the crest at the right

end. This entering wedge enabled two companies to reach the top, from which

they discovered three levels of caves on the reverse slope. They went to work

methodically, moving from right to left along the top level, burning and blasting

each cave and dugout, the flame-thrower and satchel-charge men covered by

riflemen. When work on the top level was finished, the second level of caves

and tunnels received similar treatment, and then the third and lowest level.

That night fifteen Japanese who had survived

- [397]

- the day's fighting crawled out of

the blasted caves and were killed by Americans from their foxholes. A great

amount of enemy equipment, including ten destroyed 150-mm- guns and twenty-five

trucks, was found on the south (reverse) side of Dorothy Hill, testifying

to the enemy fire power at this strong point. On 30 May, the 77th Division

also took Jane Hill on its left flank and then almost unopposed took Tom Hill,

the highest point of ground in the Shuri area, by 1700.33

-

- For nine days elements of the 96th

Division had been stalemated at the base of Hen Hill, just northeast of Shuri.

On the 30th, Company F and one platoon of Company G, 38ad Infantry, resumed

the attack on Hen Hill. Pfc. Clarence B. Craft, a rifleman from Company G,

was sent out ahead with five companions to test the Japanese positions. As

he and his small group started up the slope, they were brought under heavy

fire from Japanese just over the crest, and a shower of grenades fell on them.

Three of the men were wounded and the other two were stopped. Craft, although

a new replacement and in his first action, kept on going, tossing grenades

at the crest. From just below the crest he threw two cases of grenades that

were passed up to him from the bottom, those of the enemy going over his head

or exploding near him. He then leaped to the crest and fired at point-blank

range into the Japanese in a trench a few feet below him. Spurred by Craft's

example, other men now came to his aid. Reloading, Craft pursued the Japanese

down the trench, wiped out a machinegun nest, and satchel-charged the cave

into which the remaining Japanese had retreated. Altogether, in the taking

of Hen Hill as a result of Craft's action, about seventy Japanese were killed,

at least twenty-five of whom were credited to Craft himself. This daring action

won him the Congressional Medal of Honor.34

-

- To the left (east), Company F at the

same time engaged in a grenade battle for Hector Hill, using ten cases of

grenades in the assault on the crest. It was finally won after a satchel charge

was hurled over the top and lit in the enemy trench on the other side, parts

of Japanese bodies and pieces of enemy equipment hurtling into the sky in

the blast. Hen and Hector Hills had fallen by 1400.35

-

- On the 96th Division's left rapid

advances were made on 30 May. Roger Hill was seized when the Japanese failed

to man their combat positions quickly

- [398]

-

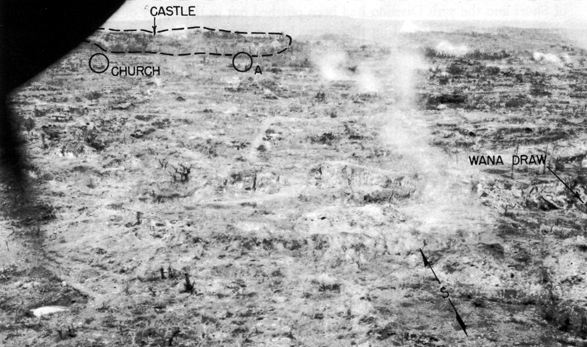

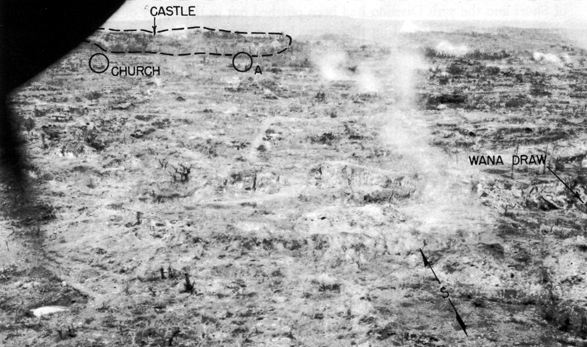

- SHURI, photographed 28 April (above) and 23 May 1945 (below). Ruins

shown in lower picture iclude Methodist Church and a 2-story concrete

structure (circle A). Dotted outline in photos indicates the castle wall.

-

-

- [399]

- enough after an artillery barrage

that had driven them to cover. They were killed to a man by the infantry,

which surprised them when they tried to reach their fighting positions. Sgt.

Richard Hindenburg alone killed six of the enemy with his BAR. The 3d Battalion,

381st Infantry, went down the western slope of the Conical hogback to find

from 75 to 100 dead Japanese on the reverse slope of Cutaway Hill. At last

the ad Battalion, 383d Infantry, reached Love Hill and dug in, although scattered

fire was still received from a machine gun in a nook of Charlie Hill and there

were a few live Japanese on Love itself. In the afternoon the 3d Battalion,

383d Infantry, left its foxholes on Oboe, where it had experienced so great

an ordeal, and proceeded down the reverse slope of the hill, finding only

a few scattered Japanese. That night the 383d Infantry expressed a heartfelt

sentiment when it reported "infinite relief to have Conical Hill behind

us." Although there had been suicidal stands in a few places by the last

of the holding force, the advances had been rapid.36

-

- On 31 May the 77th Division walked

over 100 Meter Hill at the eastern end of Wana Ridge and on into Shuri. The

marines from the vicinity of Shuri Castle moved north without opposition to

help in the occupation of the battered rubble. Overnight the enemy had stolen

away. When darkness fell on 31 May the III Amphibious Corps and the XXIV Corps

had joined lines south of Shuri and the 77th Division had been pinched out

in the center of the line at Shuri. The troops rested on their arms before

beginning the pursuit south with the coming of dawn.37

-

- Crater of the Moon

- Shuri, the second town of Okinawa,

lay in utter ruin. There was no other city, town, or village in the Ryukyus

that had been destroyed so completely. Naha too had been laid waste. Certain

villages which had been strong points in the enemy's defense, such as Kakazu,

Dakeshi, Kochi, Arakachi, and Kunishi, had been fought over and leveled to

the ground. But none of these compared with the ancient capital of the Ryukyus.

It was estimated that about 200,000 rounds of artillery and naval gunfire

had struck Shuri. Numerous air strikes had dropped 1,000-pound bombs on it.

Mortar shells by the thousands had arched their way into the town area. Only

two structures, both of concretethe big normal school at the southwestern

corner and the little Methodist

- [400]

- SHURI CASTLE BELL, with an American officer standing by. Bell is

a companion to one brought to U.S. Naval Academy by Commodore Perry

-

- [401]

- church, built in 1937, in the center

of Shuri-had enough of their walls standing to form silhouettes on the skyline.

The rest was flattened rubble. The narrow paved and dirt streets, churned

by high explosives and pitted with shell craters, were impassable to any vehicle.

The stone walls of the numerous little terraces were battered down. The rubble

and broken red tile of the houses lay in heaps. The frame portion of buildings

had been reduced to kindling wood. Tattered bits of Japanese military clothing,

gas masks, and tropical helmets-the most frequently seen items-and the dark-colored

Okinawan civilian dress lay about in wild confusion. Over all this crater-of-the-moon

landscape hung the unforgettable stench of rotting human flesh.38

-

- On a high oval knob of ground at the

southern edge of the town, Shuri Castle had stood. Walls of coral blocks,

20 feet thick at the base and 40 feet in height, enclosed the castle area

of approximately ago acres. The castle in its modern form had been constructed

in 1544, the architecture being of Chinese origin. Here the kings of Okinawa

had ruled. Now the massive ramparts, which had been battered by 14- and i6-inch

shells from American battleships, remained intact in only a few places. Inside

the castle area one could discern the outline of the rubble-strewn and pitted

parade ground. Magnificent large trees that had graced the castle grounds

were now blackened skeletons on the skyline.

-

- From the debris of what once had been

Shuri Castle two large bronze bells, scarred and dented by shell fire, were

dug out by the troops. One of them was about five feet in height, the other

three and a half. Cast about 1550, they were inscribed with characters that

may be translated as follows:

-

- In the Southern Seas lie the islands

of Ryukyu Kingdom, known widely for their scenic beauty. The Kingdom of Ryukyu

embraces the excellent qualities of the three Han states of Korea and the

culture of the Mings. Separated as it is from these nations by distance, still

it is as close to them as lips to teeth . . . .

-

- Behold! What is a bell? A bell is

that which sounds far, wide, and high. It is a rare Buddhist instrument, bringing

order to the routine of the monk. At dawn it breaks the long stillness of

the night and guards against the torpidity of sleep . . . .

-

- It will always ring on time, to toll

the approach of darkness, and to toll the hour of dawn. It will startle the

indolent into activity that will restore honor to their names. And how will

the bell sound? It will echo far and wide like a peal of thunder, but with

utmost purity. And evil men, hearing the bell, will be saved.39

- [402]

page created 10 December 2001