- Chapter XVI:

-

- Behind the Front

-

- The stubborn and protracted defense

by the Japanese of the fortified Shuri area affected every phase of logistic

and other operations in support of the Okinawa campaign, adding unforeseen

complications to the execution of a mission which in itself was of great

complexity and magnitude. As time passed far beyond the limits set in the

plans the quantity of supplies and equipment used increased in direct proportion,

while the reduction of the elaborate defenses required the expenditure of

inordinate amounts of materiel, especially ammunition. The planned capture

of the ports of Naha and Yonabaru for the delivery of cargo failed to materialize

and, as a result, the increased supplies required could not be unloaded in

sufficient quantities. The carefully integrated shipping schedules for garrison

and maintenance supplies were thereby upset. At the same time construction

of base facilities was delayed. Difficulties were compounded when, in the

last days of May and the early part of June 1945, the invading forces found

themselves fighting the weather as well as the enemy. Steady and heavy rains

severed land communications on Okinawa, and the motorized Tenth Army was bogged

down in the mud. Only through the utmost use of all available resources, energetic

improvisation, and resort to water and air transportation was it possible

to keep the supplies rolling in to the appointed place in approximately the

desired quantities and in time to defeat the enemy.1

-

- As soon as the hilly terrain behind

the Hagushi beaches was overrun by American troops, it became the scene of

feverish activity. Roads were widened and improved, supply dumps established,

antiaircraft guns emplaced, and hundreds of military installations constructed.

Tent settlements sprang up everywhere, and the dark green of pyramidal and

squad tents became as commonplace a feature of the landscape as the Okinawan

tomb. Coral was chopped away from hills and laid on the roads and airfields.

Bumper-to-bumper traffic raised clouds of dust on the main thoroughfares in

dry weather and splattered along through deep mud in wet. Telephone service

soon linked all Army and Navy

- [403]

Large supply installation in Kakazu area

|

Route 1 near Kadena

|

Main west-coast telephone cable

|

-

- SUPPLY AND COMMUNICATIONS INSTALLATIONS

-

- [404]

- installations, and Signal Corps troops

also established an elaborate radio communication net and service to American

bases in the rear. There were 170,000 Americans on the island a month after

the landings, and about 245,000 on Okinawa and neighboring islands at the

end of June.2

-

-

- Bringing the Supplies Ashore

- Unloading of the assault shipping

was nearly completed by 16 April, ahead of schedule.3

(See Appendix C, Table No. 7.) Further progress was satisfactory through 6

May. Thereafter, however, the discharge of supplies failed to keep pace with

unloading plans. Between 7 May and 15 June tonnage unloaded was more than

2,00,000 measurement tons behind schedule. However, this was largely offset

by the earlier achievements, and the cumulative effect was not evident until

5 June. The chief difficulty was the failure to capture the port of Naha with

its harbor and dock facilities as early as planned. Unloading continued for

the most part over the reef and beaches in the Hagushi area long after it

was expected that they would have been abandoned in favor of rehabilitated

port facilities. (See Appendix C, Chart No. 3.) High winds, heavy rains, frequent

air raids, and equipment shortages all contributed to the delays and the cumulative

deficiencies. Particularly onerous was the necessity of selective discharge

of cargo to bring ashore critical items of supply. Sometimes dock gangs had

to be pulled off ships prior to unloading and placed on "hot" ships

as emergencies developed. In the face of all these difficulties, more than

2,000,000 measurement tons of cargo were unloaded on Okinawa from 1 April

to 30 June, an average of some 22,200 tons a day. (See Appendix C, Table No.6.)

-

- To supplement the tonnage unloaded

at the Hagushi beaches, Tenth Army developed a number of unloading points

at other places along the coasts of Okinawa. Such points were opened between

5 and 9 April in northern Okinawa for close support of III Amphibious Corps

in its rapid advance northward during the early stages of the operation. After

the marines moved south to take part in the drive against the main enemy position,

work was rushed to develop unloading facilities at Machinato on the west coast.

By 25 May LCT's were being unloaded at a temporary sand causeway. At the same

time, temporary unloading

- [405]

- points were developed on the coast

between Machinato and Naha in further support of the III Corps. On 7 June,

the port of Naha was opened for the use of LCT's and the rehabilitation of

harbor and dock facilities was begun. It was planned that by the end of June

the bulk of west-coast tonnage would be unloaded at Naha and that the Hagushi

beaches would gradually be abandoned.

-

- Unloading on the east coast of Okinawa

began in the middle of April, and use was successively made of beaches at

Chimu Bay, Ishikawa, Katchin Peninsula, Awase, and Kuba. Yonabaru was captured

on 22 May and supplies were unloaded there on 1 June. A ponton pier was started

there for LST's and smaller craft a week later and was completed on 12 June.

In the last stages of the campaign an emergency unloading point was opened

at Minatoga on the southeast coast on 9 June and was operated for two weeks.

-

- By 30 June 1945 about 20 percent of

all tonnage unloaded on Okinawa had been brought ashore at points other than

the Hagushi beaches, amounting to nearly 400,000 measurement tons of cargo.

In one respect, however, the use of unscheduled supply points contributed

to the delays of unloading: as each new beach was opened in immediate support

of the assault, available lighterage, trucks, and personnel were dispersed

over a number of places, thereby materially slowing operations at the original

unloading points. In addition, much of the cargo handled over the new beaches

was not discharged directly from ships but from landing craft that had loaded

at previously established dumps at Hagushi, Awase, and Kuba and had sailed

down the coast.

-

- As a result of slow unloading, ships

awaiting discharge accumulated at the various anchorages and presented fine

targets for Japanese air attacks. While strenuous efforts were continuously

made to speed unloading operations and return the ships to safer areas, the

originally planned schedule of resupply shipping could not be adhered to.

Emphasis was placed on calling up ships loaded with supplies that were in

great need on the island at the particular time. Calling up only the number

of such ships which could be expeditiously handled was not always possible

because the requirements were so great, particularly in the case of ammunition

ships. 4

-

- Delivery of Supplies to the Front

- Responsibility for supplying the assault

troops passed smoothly, during the initial stages, from division to corps

and then to the Island Command, the Army logistic agency, on 9 April. Depot

and dump operations for the Island

- [406]

- Command were handled by the 1st Engineer

Special Brigade until 24 May, when Island Command took over direct operational

control of supply installations. All units normally drew supplies in their

organic transportation from the Island Command supply points. These were first

established in the area behind the Hagushi beaches, but forward supply points

were opened farther south as the action moved toward that end of the island.

Initially an ammunition supply point was established for each division, and,

as operations progressed, these points were consolidated and new ones set

up farther forward.

-

- No unusual difficulties were encountered

in moving up supplies to the troops until the latter part of May. When the

heavy rains started on 20 May and continued day and night for two weeks, the

main supply roads linking the forward and rear areas were washed out and movement

of vehicles became impossible. The rainy period, moreover, coincided with

the break-through at Shuri that started the troops moving rapidly south away

from all established supply points. It became necessary to resort to water

transportation to bring supplies to the forward dumps. In the interim the

7th Division, which was making the main effort in the sector at the time,

was supplied by LVT along the coast. XXIV Corps established a supply point

at Yonabaru on 31 May, and lighterage was made available by the Island Command

and the Navy for the delivery of the necessary supplies. The first supplies

arrived at Yonabaru on LCT's on 1 June. Several LCT's also ferried service

troops and artillery forward and evacuated casualties.

-

- As the pursuit of the retreating Japanese

continued, the Corps turned the Yonabaru supply point over to Island Command

and concentrated on a new forward unloading point at Minatoga, on the southern

coast. To ensure the steady flow of ammunition to XXIV Corps units, a cargo

ship and three LST's loaded entirely with that class of supply were anchored

off Yonabaru and Minatoga and used as floating ammunition supply points. The

7th Division received some supplies by LVT at Minatoga on 6 June. The initial

shipment of four LCT's loaded with rations and fuel and an LST with ammunition

arrived on 8 June. Forty-four LVT's loaded with ammunition and bridging material

were sent to Minatoga aboard an LST on 9 June. Shipments to the new supply

point were continued from both east and west coasts of Okinawa by LST and

LCT, with the LVT's being used as lighterage from ship to shore. During much

of this time, supply of the assault elements on the line was almost entirely

by hand carry. On the west coast III Amphibious Corps was being supplied ammunition

by a cargo ship, an LST, and about seventy DUKW's making daily trips

- [407]

- Ship-to-shore supply causeway at Hagushi beaches

-

- Handling supplies at 196th Ordnance dump

-

- Supply trucks pulled through bad spot by 302d Combat Engineers

-

- MOVING SUPPLIES

-

- [408]

- from rear areas, all unloading at

Naha. Thirty-four LVT's also made a daily trip from the Hagushi beaches to

advance Corps positions along the coast.

-

- Air delivery was also utilized at

this time to bring supplies forward. The Air Delivery Section of III Amphibious

Corps was responsible for all air drops on the island. The section operated

from CVE's until 18 April, and thereafter from Kadena airfield. Using torpedo

bombers rather than C-47's, primarily because more accurate drops could thus

be made, the section delivered a total of 334 short tons of supplies in 830

planeloads. Most of the air drops were to III Amphibious Corps units, particularly

the 1st Marine Division, whose front-line elements were supplied almost exclusively

by air between 30 May and 9 June, when the roads in its area were impassable

even to tracked vehicles. The tonnage delivered by air to XXIV Corps in the

week a-9 June was small but, because of its emergency nature, important. Supplies

thus dropped consisted in the main of ammunition and rations.5

-

- Maintenance and construction of supply

roads were impeded by the lack of good road-building material and by rapid

deterioration from rainy weather and heavy traffic. In the XXIV Corps zone

the limestone coral used for road building in the early stages of the campaign

proved to be unsuitable, and extensive use had to be made of rubble from destroyed

buildings and stone walls. A rock crusher was not available. As the Corps

drove southward, the lack of adequate sources of coral limestone became acute

and the use of building rubble had to be continued. When a rock crusher was

made available at the end of the first week in June, it was set up and operated

in a limestone quarry and then moved to a site where the excellent stone from

the razed Shuri Castle could be used. It was at this time, moreover, that

the problem of road maintenance became overwhelming. A 12inch rainfall between

as May and 5 June forced the abandonment of the two main supply roads serving

the Corps. One of these, Route 13 along the east coast, was not reconstructed

during the battle; the engineers concentrated on keeping Route 5, down the

center of the island, in operation, as well as the roads running south from

Yonabaru and Minatoga, to which supplies were moved by water. In the Marine

zone on the west side of the island, only the continuous labor of all engineer

units and rigid traffic control kept Route 1 open. By the end of June main

supply roads had been developed from Chuda to Naha on the west coast (Route

1), from Chibana to Shuri in the center (Route 5), from Kin to Yonabaru on

the east coast (Route 13), and at six intermediate points across the island.

- [409]

- Approximately 164 miles of native

roads had been reconstructed and widened for two-lane traffic, 37 miles of

two-, three-, and four-lane roads had been newly constructed, and a total

of 339 miles of road was under maintenance.

-

- Supply Shortages

- Providing an adequate supply of ammunition

to support the sustained attacks on the Shuri defenses constituted the most

critical logistical problem of the campaign. The resupply of ammunition beyond

the initial five CINCPOA units of fire had been planned for a 40-day operation;

the island was not officially declared secure until L plus 82 (22 June).6

The sinking of three ammunition ships by enemy action on 6 and 27 April and

damage to other ships resulted in a total loss of 21,000 short tons of ammunition.

The unloading of ammunition was, moreover, never rapid enough to keep pace

with expenditures, particularly by the artillery, and at the same time to

build up ample reserves in the ammunition supply points. Further, it was found

that the shiploads of all calibers balanced according to the CINCPOA unit

of fire prescription did not fit the needs of a protracted campaign; the requirements

for artillery ammunition far exceeded those for small-arms ammunition and

resulted in hasty, wasteful unloading and constant shortages.

-

- The ammunition situation first became

critical when XXIV Corps developed the Naha-Shuri-Yonabaru defense line during

the second week of April. The ammunition expenditures in the large-scale artillery

attacks mounted rapidly. As the rate of discharge from the ships failed to

keep pace, the supplies on hand dwindled. The plans for the Corps attack designed

to penetrate the Japanese positions called for an expenditure of 14,800 tons

of artillery ammunition plus supply maintenance of some 1,000 tons a day.

To conserve supplies, command restrictions on artillery ammunition expenditures

were imposed on 9 April. The Corps attack was delayed until 19 April, partly

in order to accumulate sufficient stocks and reserves. This was accomplished

in time by means of greater unloading efforts, making available all resupply

ammunition, and diverting III Amphibious Corps' stocks to XXIV Corps.

-

- After the attack of 19 April ammunition

expenditures continued to mount. By the end of the campaign a total of 97,800

tons of ammunition had been expended. XXIV Corps alone consumed about 64,000

tons between 4 April and 21 June, and restrictions on daily expenditures were

continuously in force in its zone until L plus 61 (1 June). In spite of restrictions

an average of more than

- [410]

- 800 tons of ammunition was expended

daily by Corps units. (See Appendix C, Table No. 10.)

-

- About the middle of April a critical

shortage of 155-mm. ammunition developed, and on 17 April Tenth Army had to

call up four LST's loaded only with ammunition for 155-mm. guns and howitzers

from the reserves in the Marianas. Subsequently, additional emergency requisitions

on the reserves were necessary. CINCPOA was also requested to divert ammunition

resupply shipments from canceled operations, as well as some originally intended

for the European Theater of Operations, to Okinawa in order to alleviate the

shortages. On 21 May Tenth Army had to request an emergency air shipment of

50,000 rounds of 81-mm. mortar ammunition, of which more than 26,000 rounds

were received between 28 May and 9 June.

-

- However, the expenditure of large-caliber

ammunition (75-mm. and larger) on the average was within 1 percent of the

over-all requirements estimated in the planning phase. Of the total of 2,116,691

rounds expended (including 350,339 rounds lost to the enemy), the greatest

expenditure was in 105-mm. howitzer ammunition, with 1,104,630 rounds fired

and an additional 225,507 rounds lost to the enemy. (See Appendix C, Table

No. 8 and Chart No. 4.) Although this exceeded the total estimated requirements

for 105-mm. howitzer ammunition by nearly 8 percent, the expenditure was well

within the limits of available supply for the period.

-

- Shortages of 4.2-inch chemical mortar

ammunition, resulting in large part from an unusual percentage of defective

fuses, were overcome by the use of surplus Navy stocks and by air shipments

of replacement fuzes.

-

- The supply of aviation gas on the

island always bordered on the critical. Although no air mission's had to be

canceled, generally the two airfields barely had enough gas to carry out all

scheduled missions. The relative scarcity of aviation gas was due principally

to slow unloading and the lack of bulk storage facilities ashore. Gas tanks

were not completed until the end of April; until then gas had to be brought

ashore in drums and cans-a slow, laborious process. The use of DUKW's to take

gas directly from the ships to the fields materially expedited unloading.

Reserves on hand, however, were never plentiful, and, when a tanker failed

to arrive on schedule at the end of April, Tenth Army had to call on the Navy

to supply the gas for land-based aircraft from fleet tankers.7

- [411]

- The loss of light and medium tanks

during the campaign, much heavier than had been expected, caused another critical

shortage and replacements could not be secured in time. Tenth Army reported

the complete loss of 147 medium tanks and q. light tanks by 30 June; replacements

were requested from Oahu on 28 April but these had not arrived by the end

of the campaign. As an emergency measure, all the medium tanks of the 193d

Tank Battalion, attached to the 27th Division, were distributed to the other

tank battalions on the island. XXIV Corps tank units received fifty of these

tanks which contributed materially to combat effectiveness. The 193d, however,

could not be reequipped and returned to combat.

-

-

- Hospitalization and evacuation facilities

for battle casualties on Okinawa were also strained by the fierce and costly

battle against the Japanese defenses, resulting in higher battle casualties

than had been expected. (See Appendix C, Table No. 3.) The nonbattle casualties,

however, were much lower than anticipated, and the low incidence of disease,

with the corresponding reduction of the use of facilities for these long-term

cases, provided welcome hospital and surgical facilities for the large number

of wounded.8

-

- In the normal course of events on

Okinawa, a man hit on the battlefield was delivered by a collecting company,

in a jeep ambulance, weasel, or weapons carrier, to a battalion aid station

located from two to four hundred yards behind the lines. After treatment he

was carried by standard or jeep ambulance to a collecting station, the first

installation equipped to give whole-blood transfusions. The next stop was

the division clearing station, to which portable surgical hospitals were attached.

Finally, the patient would reach a field hospital, from four to six thousand

yards behind the front. Evacuation to the field hospitals functioned satisfactorily

on Okinawa until the end of May, when the heavy rains made the roads impassable.

Evacuations from the divisions south of Naha-Yonabaru ceased. It became necessary

to evacuate casualties by LST from Yonabaru on the east coast on a June and

from Machinato on the west

- [412]

-

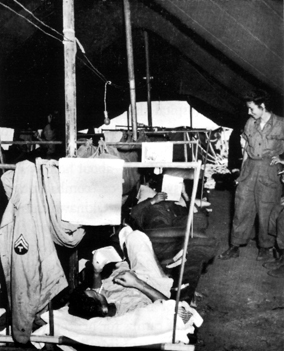

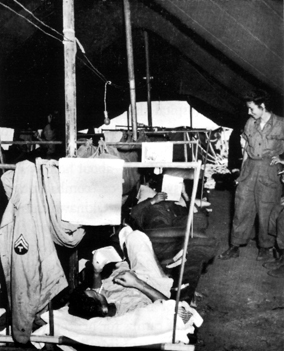

- MOVEMENT OF WOUNDED on Okinawa was difficult. Wounded had to be carried

part of the way by stretcher before they could be placed on ambulance

jeeps taking them to hospital ships or field hospitals.

-

-

- [413]

- coast on 31 May. By 10 June water

evacuation from XXIV Corps zone had been extended south to Minatoga. In the

III Amphibious Corps sector at Itoman water evacuation was not feasible because

of the reef and enemy fire. As a result, evacuation by L-5 artillery liaison

planes was instituted. The planes landed on a stretch of concrete highway

just north of Itoman and delivered the patients to Chatan. On 15 June air

evacuation of XXIV Corps casualties from Minatoga was begun. By the end of

June, 1,232 casualties had been evacuated by cub planes to the field hospitals.

-

- By the end of April six field hospitals

and one Marine evacuation hospital, with a total bed capacity of 3,000, were

in operation. At the end of the campaign on 21 June available hospital beds

for combat casualties had increased to only 3,929, in addition to 500 convalescent

beds and 1,802 garrison beds. The small number of beds was chiefly responsible

for the policy, applied in the first six weeks of the campaign, of immediately

evacuating casualties to the Marianas. As a result of this policy many so-called

"white" casualties, that is, casualties requiring two weeks or less

of hospitalization, were evacuated from the island and lost to their units

for considerable periods of time. On 16 May, in an attempt to stop this wholesale

evacuation of a valuable source of trained replacements, Tenth Army instructed

the hospitals to hold "white" cases to the limit of their capacity.

Both corps tried to stem the losses by establishing convalescent camps-XXIV

Corps on 6 May and III Amphibious Corps on 29 May. These camps alleviated

conditions but hospital facilities continued to be strained after each of

the great offensives. On 26 and 27 May all evacuation from Okinawa was suspended:

the heavy rains made the airfields unusable, and no hospital ships were- available

for surface evacuation. The hospital bed situation was critical until air

evacuation was resumed on 28 May. A total of 30,848 patients, or almost 80

percent of all battle casualties, was evacuated from Okinawa by 30 June-about

half by air and half by ship.

-

- Neuropsychiatric or "combat fatigue"

cases were probably greater in number and severity in the Okinawa campaign

than in any other Pacific operation. Such cases resulted primarily from the

length and bitterness of the fighting, together with heavy hostile artillery

and mortar fire. The influx of from three to four thousand cases crowded the

field hospitals and resulted in needless evacuations from the island. Treatment

was instituted as far forward as possible in the hope of making it more effective

as well as of retarding the flow to hospitals. Rest camps for neuropsychiatric

cases were established by divisions in addition to the corps installations.

On 25 April Tenth Army opened one field

- [414]

- hospital to handle only such cases.

Early treatment produced good results. About half of the cases were finally

treated in divisional installations; the other half, comprising the more serious

cases, were treated in the field hospitals. About 80 percent of the latter

were returned to duty in ten days, but half of these had to be reassigned

to noncombat duties.

-

- Fears that Okinawa was a disease-ridden

island where the health of American troops would be gravely menaced proved

unfounded. Surveys made in April revealed no schistosomiasis or scrub typhus

and very little malaria; about 30 percent of the natives, however, were found

to be infected with filariasis. Institution of sanitation control measures,

such as DDT spraying from the air at 7- to 20-day intervals and the attachment

of disease control units to combat organizations, helped, together with the

general favorable climatic conditions, to prevent large-scale outbreaks of

communicable diseases on the island. As a result the net disease rate for

the troops on Okinawa was very low.

-

-

- One of the most puzzling questions

confronting the planners of the Okinawa operation had been the probable attitude

of the civilian population. It was very soon apparent that the behavior of

the Okinawans would pose no problems. In the first place, only the less aggressive

elements of the populace remained, for the Japanese Army had conscripted almost

all males between the ages of fifteen and forty-five. Many of those who came

into the lines were in the category of displaced persons before the invasion

began, having moved northward from Naha and Shuri some time before. Others

had been made homeless as the fighting passed through their villages. Casualties

among civilians had been surprisingly light, most of them having sought the

protection of the caves, and some, including whole families, having taken

refuge in deep wells.

-

- The initial landings brought no instances

on Okinawa of mass suicide of civilians as there had been on the Kerama Islands,

although some, particularly of the older inhabitants, had believed the Japanese

terror propaganda and were panic-stricken when taken into American custody.

While there appeared to be only a few cases of communicable diseases and little

malaria, most civilians, living in overcrowded and unsanitary caves, were

infested with lice and fleas.

-

- A frugal and industrious people, with

a low standard of living and little education, the Okinawans docilely made

the best of the disaster which had overtaken them. With resignation they allowed

themselves to be removed from

- [415]

-

- MILITARY GOVERNMENT set up headquarters in Shimabuku at beginning

of the Okinawa campaign. Tent city (upper left) was quickly established,

and registration of military-age civilians was started (upper right).

Many Okinawan men (lower left) were given jobs carrying supplies to American

troops, while others (lower right) helped to distribute food supplies

to displace persons.

-

-

- [416]

- their homes and their belongings to

the special camp areas which soon supplanted the initial stockades as places

of detention 9

The principal areas chosen initially for civilian occupation were Ishikawa

and the Katchin Peninsula in the north, and Koza, Shimabuku, and Awase in

the south. Military Government supplied the minimum necessities of existence-food,

water, clothing, shelter, medical care, and sanitation. Food stores sufficient

to take care of civilian needs for from two to four weeks were discovered;

additional quantities were available in the fields. Growing crops were harvested

on a communal basis under American direction. Horses, cows, pigs, goats, and

poultry, running wild after eluding the invading troops, were rounded up and

turned over to the civilian camps.

-

- There was no occasion for use of the

occupation currency with which American troops had been supplied, in exchange

for dollars, before landing; no price or wage economy existed in the zone

of occupation. For a time the population had to devote its energies solely

to the problems of existence.

-

- Control of civilians on Okinawa was

vested in a Military Government Section whose operation was a command function

of Tenth Army. The organization provided for four types of detachments, each

consisting of a number of teams. The first type accompanied assault divisions

and conducted preliminary reconnaissance; the second organized Military Government

activities behind the fighting front; the third administered the refugee civilian

camps; and the fourth administered the Military Government districts. It proved

difficult to secure adequate numbers of certain types of personnel for Military

Government, especially interpreters who were sufficiently skilled in the Japanese

language. Before the invasion seventy-five men were assigned for this duty;

when it became apparent that this number was insufficient, an additional allotment

of ninety-five interpreters was secured. As the campaign progressed, minor

shortages of cooks, military police, and medical corpsmen developed in the

camps for displaced civilians. In spite of these shortages, detachments that

were originally designed to operate camps containing 10,000 civilians often

found it necessary to care for as many as 20,000.

-

- The number of Okinawans under control

of Military Government rose rapidly in the first month of the invasion until

by the end of April it amounted to 126,876. Because of the stalemate at the

Shuri lines the increase during May was gradual, the total number of civilians

at the beginning of June being 144,331.

- [417]

- DEVELOPMENT OF AIRFIELD at Kadena (photographed 20 April 1945) was rapid.

-

- REHABILITATION OF PORT at Naha was in progress when this picture

was taken, 19 June 1945.

-

- [418]

- But during the first three weeks of

June, after the break-through on the Shuri line, the number again rose sharply

until, at the conclusion of the fighting, the Okinawans under Military Government

totaled approximately 196,000.10

-

-

- The purpose of the base development

plans for Okinawa and le Shima was the construction of advance fleet and air

bases and staging facilities for future operations. Initially, however, all

construction work was directed to the support of the assault troops. Main

supply and dump roads were improved, Yontan and Kadena airfields were put

into operation, and work was begun on the construction of bulk storage facilities

for gasoline with offshore connections to tankers.11

-

- In the original plans many more islands

in the Ryukyus chain had been selected for capture and development as American

bases, particularly for aircraft. No less than five additional islands-Okino

Daito, Kume, Miyako, Kikai, and Tokuno-had been scheduled for invasion in

Phase III of ICEBERG and were to be developed as fighter and B-29 bases and

radar stations. In the course of time, as reconnaissance revealed that some

of the islands were unsuitable for the purposes intended, plans for their

capture were canceled. Of the five, only Kume was taken, on 26 June, and not

for use as an air base but in order to enlarge the air warning net for the

Okinawa island group.

-

- The cancellation of the Phase III

projects greatly affected the plans for base development on Okinawa and Ie

Shima. In some cases most of the resources and troops intended for the abandoned

operations were made available for the work on Okinawa. At the same time,

however, some of the airfield construction projects were also transferred,

thereby sizeably increasing the task of the Okinawa construction troops. In

one case favorable estimates of construction possibilities on Okinawa and

Ie Shima were responsible in large part for the decision to abandon one of

the most important operations planned for Phase III-the Miyako operation.

On 9 April Tenth Army reported to Admiral Nimitz that a detailed reconnaissance

of the terrain of Okinawa revealed excellent airfield sites for Very Long

Range bombers (VLR) on the island. As a result, Admiral

- [419]

- Nimitz recommended to the Joint Chiefs

of Staff that the seizure of Miyako Island for development as a VLR bomber

base be abandoned in favor of a more intensive construction program for Okinawa

and le Shima. The Joint Chiefs approved and the Miyako operation was canceled

on 26 April. Accordingly, base development plans were changed to provide for

18 air strips on Okinawa and 4 on Ie Shima, instead of the 8 and 2 originally

planned respectively for the two islands. Construction of fields on Okinawa

was to center on the provision of facilities for B-29 operations, while Ie

Shima was to be developed primarily as a base for VLR fighter escorts.

-

- There was concern over interruptions

to the progress of the greatly expanded Okinawa program. The extremely heavy

rains at the end of May practically stopped all construction work until about

15 June, as troops working on the airfields had to be diverted to maintenance

of the main supply roads to the assault troops. Although the cancellation

of the Miyako project made available more men for the base program on Okinawa,

only 31,400 of the 80,000 construction troops needed had reached the island

by 22 June 1945. It was impossible to keep abreast of scheduled dates of completion.

The delays in unloading and failure to uncover airfields and ports on schedule

also contributed to the delay in the base development program.

-

- Work on fighter airfields was initially

given the highest priority in order to provide land-based air cover during

the assault. By 10 April Kadena and Yontan airfields had been reconditioned

for successful operations. American engineers found that the Japanese airfields

were poorly constructed, being surfaced with only a thin layer of coral rock

and lacking adequate drainage. The runways had to be completely rebuilt, with

a foot of coral surfacing added. By the end of May construction was in progress

on ten different bomber and fighter strips on Okinawa and le Shima. Of these

only the fields at Yontan and Kadena and one of the fighter strips on Ie Shima

were near completion. The first American air strip built on Okinawa was the

7,000-foot medium bomber runway at Yontan, completed on 17 June. By the end

of June a 7,500-foot VLR strip at Kadena was 25 percent complete, two 5,000-foot

fighter strips at Awase and Chimu were ready for operation, an 8,500-foot

VLR strip at Zampa Point was 15 percent complete, and construction was under

way for VLR and medium-bomber strips at Futema and Machinato.

-

- Harbor development began at the end

of April with the construction of a 500-foot ponton barge pier on the Katchin

Peninsula at Buckner Bay. Tem-

- [420]

- porary ponton barge piers were built

at other sites on the bay-at Kin on Chimu Bay, at Machinato, and at the mouth

of the Bishi River. By the end of June an 800-foot ponton barge pier was under

construction at Yonabaru. Preparations for building permanent ship piers and

cargo berths were also under way. At Naha troops had begun clearing the harbor

of wrecks and debris at the beginning of June; several months would be required

before this work would be completed and Naha could serve as a major port.

-

- By the end of the Okinawa campaign

the full realization of the plans for the development of major air and naval

bases in the Ryukyus still lay in the future. Most of the airfields would

not be completed for two or three months, although fighters were flying from

some to attack Kyushu. The naval base in Buckner Bay was far from complete

when the war ended. It was not until the last night of the war that Okinawa-based

B-29'S carried out their first and last offensive mission against the Japanese

homeland.

- [421]

page created 10 December 2001