- Chapter XVII:

-

- The Enemy's Last Stand

-

- "Ushijima missed the boat on

his withdrawal from the Shuri Line," General Buckner declared on 31 May

as he reformed his ranks for the pursuit and final destruction of the 32d

Army. "It's all over now but cleaning up pockets of resistance. This

doesn't mean there won't be stiff fighting but the Japs won't be able to organize

another line." Other officers also did not credit the enemy with the

ability to execute an orderly withdrawal 1

This optimism proved soon to be largely unfounded. It was to be learned that

the enemy had withdrawn his forces from Shuri effectively and in time to organize

a new line in the south. The enemy's maneuver, though it did not result in

setting up a formidable line of defense, was to necessitate more than three

crowded weeks of pursuit and fighting by the American troops to bring organized

resistance to an end.

-

-

- On 31 May General Buckner extended

the Army boundary along the road joining the villages of Chan, Iwa, and Gushichan.

He ordered his two corps to complete the encirclement of Shuri in order to

cut the remaining Japanese troops into large segments. General Buckner and

his staff still hoped to isolate a large portion of the 32d Army and

prevent its withdrawal from Shuri; thus the two corps were directed to converge

at Chan "in order to pocket enemy north this point." III Amphibious

Corps was then to secure Naha and its airfield while XXIV Corps drove rapidly

southeast to prevent the enemy from retiring into the Chinen Peninsula. General

Buckner expected the Japanese, without skilled men or adequate transportation

or communications, and hindered by boggy roads, to experience trouble and

disorder during their mass retreat.2

-

- Mud was a major concern of American

commanders. Nearly twelve inches of rain had fallen during the last ten days

of May and more was expected during the first part of June. Although 400 trucks

had been used on 30 May to dump coral and rubble into the mudholes on Route

5, the main north-south

- [422]

- road through the center of Okinawa,

it was closed the following day to all but the most essential traffic. Other

supply routes along the east and west coasts were in almost impassable condition.

At the time when General Buckner ordered his troops to "drive rapidly,"

supply trucks were moving toward the front only as fast as they could be dragged

by winches or bulldozers through the numerous quagmires. Units on each flank

were using boats or amphibian tractors to transport supplies from rear areas

to forward dumps, but they still faced the problem of moving food and ammunition

from the beaches to the front-line foxholes. Center divisions were under a

still greater strain. Much of the ammunition, food, and water was carried

forward by reserve units-sometimes by men from the assault companies.

-

- "We had awfully tough luck,"

said General Buckner, "to get the bad weather at the identical time that

things broke." His deputy chief of staff considered the mud to be as

great a deterrent to the attack as a large-scale enemy counterattack.3

-

- The Japanese Make Their Escape

- The XXIV Corps occupied the southernmost

positions of the American front. General Hodge shifted the 7th Division toward

the east and ordered the 96th to move south, relieve the 32d Infantry, and

take up the western end of the Corps line. The 77th Division became responsible

for protecting the rear of the 96th and for mopping up the part of the Shuri

line which was in the XXIV Corps sector. By evening of 31 May, the 7th and

96th Divisions reached the Corps' objective, and they were ready to start

south on the following morning. 4

-

- The lines of the III Amphibious Corps

stretched from Shuri to a point 1,000 yards southeast of Naha; its nearest

position was more than 3,000 yards from the dominating ground near Chan where

General Buckner still hoped to converge spearheads of his two corps and to

reduce Ushijima's force to segments. This hope disappeared by the night of

31 May, when the performance of the 96th and 7th Divisions .indicated that

General Ushijima had already accomplished his sly withdrawal despite the difficulties

of mud and communications. When it became apparent that the Japanese withdrawal

had frustrated American hopes of splitting the enemy forces, Tenth Army revised

its plans

- [423]

- and permitted the III Amphibious Corps

to attack down the west coast and the 7th Division to proceed down the east

flank.5

(See Map No. XLVI.)

-

- When the attack toward the south began

on the first day of June, it was planned that the Marines should destroy the

remaining Japanese rather than isolate them. Patrols from the III Amphibious

Corps soon discovered that only a thin shell of defenses remained near Shuri.

General Geiger decided, therefore, to push the 1st Marine Division directly

south to seal the base of Oroku Peninsula, and he also made plans for an amphibious

landing by the 6th Marine Division on the tip of the peninsulas.6

-

- Four miles south of the front line

loomed another coral escarpment, the largest on the Okinawa battlefield. This

was the Yuza-Dake-Yaeju-Dake, which formed a great wall across the southern

end of the island that had been visible since the early days of the campaign.

The central part of the island between the American front lines of 31 May

and the Yaeju-Dake consisted of a series of comparatively small rounded hills

and uneven low ridges; a few larger hills stretched across the base of the

Oroku Peninsula on the west side of the island. The highest hills south of

the landing beaches were on the east side of southern Okinawa and on Chinen

Peninsula, which consisted entirely of hilly ground except for the narrow

strip of flat land at the shore.

-

- Pursuit in the Mud

- Dense fog banks covered southern Okinawa

on the morning of I June. Visibility extended for only a few yards and mud

was ankle-deep as the Americans attacked south to catch up with Ushijima's

escaped army before it should have time to burrow into a new defensive line.

On 1 June the Japanese defended two hills in front of the 7th Division, and

during 1-2 June they made a solid stand in the zone of the 96th near Chan.

Otherwise there was only spotty resistance of delaying and nuisance value

until 6 June. On that day the pace of the American troops was retarded by

vigorous enemy action to the front and by the overextension of the supply

lines of the front-line units.7

-

- Most of the hills were either defended

by thin enemy forces or had been completely abandoned, and a lack of skill

was noticeable among the enemy troops encountered. As American troops approached

their positions the Japanese of-

- [424]

- fered ineffectual fire until the attack

drew close, and then frequently tried to escape by running across open ground.

They became easy targets for riflemen and machine gunners, who were quick

to see and respect skill in their opponents and as quick to feel disdain for

spiritless mediocrity. S/Sgt. Lowell E. McSpadden, a member of the 383d Infantry,

expressed the attitude of the infantrymen toward these inferior troops when

he stepped up behind two Japanese soldiers without being seen, tapped one

on the shoulder, and then shot both with a .45caliber pistol which he had

borrowed for the purpose.8

-

- After the first day of the pursuit,

rain was more troublesome and constant than enemy interference. The 184th

Infantry waded south and east over the green and rain-soaked hills on Chinen

Peninsula against light opposition that indicated an absence of enemy plans

for a defense of that area. General Arnold, moving to speed up operations,

committed the 32d Infantry to patrolling the northern part of the peninsula.9

Late in the afternoon of 3 June, patrols from the 1st Battalion, 184th, reached

the southeast coast of Okinawa near the town of Hyakuna and completed the

7th Division's first mission: It had been, General Buckner said, a magnificent

performance.10

-

- General Hodge doubted that his corps

could have continued its pace had it not been for previous experience in the

marshes of Leyte.11

Only flimsy resistance faced the 1st Marine Division, but its supply system

had collapsed and the battalions had to rely upon air drops or carrying parties.

By 3 June the gap in depth between the two corps had increased to 3,000 yards,

and the 383d Infantry was subjected to harassing fire from its exposed right

flank. To protect his corps' flank, General Hodge sent the 305th Infantry,

77th Division, south to fill the increasing void.12

-

- Toward the Yaeju-Dake

- In the meantime the 2d Battalion,

5th Marines, crossing the Corps boundary north of Chan, attacked southwest

through Tera and secured Hill 57 and the high ground south of Gisushi, thus

reducing the gap to 1,000 yards.

-

- With the elimination of possible defensive

terrain on Chinen Peninsula and in central southern Okinawa, it was becoming

evident by the evening of 3 June that General Ushijima intended to stage his

final stand on the southern

- [425]

-

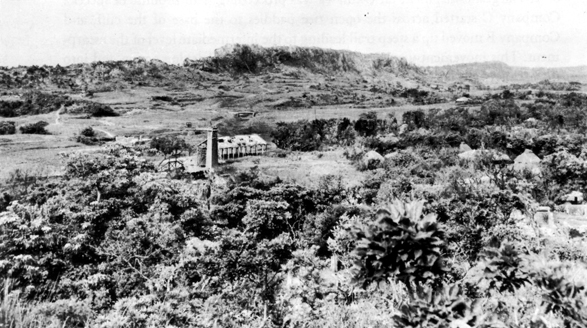

- MUD AND SUPPLY were major problems in pursuing the

Japanese southward from Shuri. Success depended largely on ability to

move American supplies over bad roads. Tractor (above) is pulling a reconnaissance

car uphill from portable bridge in the hollow. When roads became impassable

to motor vehicles (below), horses were used.

-

-

- [426]

- tip of the island, almost certainly

on the Yaeju-Dake Escarpment, which lay within the zone of the III Amphibious

Corps. Moreover, if the XXIV Corps maintained its pace for one or two days

longer, as seemed likely, it would have secured its portion of southern Okinawa.

In order to deny the enemy a breathing spell before the final period of combat,

General Buckner shifted the Corps' boundary to the west so that the entire

escarpment fell within the zone of the XXIV Corps. Effective at noon on 4

June, the boundary between the corps changed from the road connecting Iwa

with Gushichan to the road connecting Iwa with Yuza, Ozato, and Komesu. 13

(See Map No. XLVIL)

-

- Shifting their direction of attack

on 4 June to the southwest, General Hodge's troops moved across the small,

tidy fields, the rice paddies along the sea, and the hills luxuriantly green

from the continuing spring rains. By midafternoon the 7th Division had secured

more than 6,000 yards of coast line and had reached the soggy banks of the

Minatoga River. Infantrymen waded the swollen stream, the only bridge having

been destroyed. The 96th joined on the west to extend the Corps line from

Minatoga to Iwa. To the south the Japanese had prepared the outposts of their

next important line, which was to be their last. Behind the American lines

the supply routes, now stretched beyond an unbridged river, were strained

to the limit. Commanders immediately explored the possibilities of landing

supplies at Minatoga. During the several days that followed, the American

troops crowded steadily but more cautiously forward against a heavy and determined

opposition that was reminiscent of previous fighting and suggested that the

enemy's last line was close at hand.14

-

-

- It was only by chance and whim that

the Oroku Peninsula was defended by the Japanese after the Shuri line was

abandoned. Before 1 April enemy naval units were responsible for this two-by-three-mile

peninsula and the installations emplaced there to protect the airfield and

the city of Naha. A few days before the American landings took place, but

after the threat of invasion made it either impossible or unnecessary for

the naval units to continue with their more specific missions, they were consolidated

under the Okinawa Base Force. Most of the Navy personnel congregated

on Oroku Peninsula. The Okinawa Base

- [427]

- Force, commanded by Rear Admiral

Minoru Ota, was in turn responsible to the 32d Army, toward which Ota

adopted a policy of complete cooperation.15

-

- The total strength of enemy naval

units on Okinawa was originally nearly 10,000 men; less than a third of that

number, however, belonged to the Japanese Navy, the majority being either

recently inducted civilians or Home Guards. Of the men who made up the construction

units, the naval air units, the Midget Submarine Unit, and the other

organizations that became a part of the Base Force, only two or three hundred

had received more than superficial training for land warfare. None of these

naval units participated in combat until the counterattack of 4 May, when

a limited number of naval troops were sent to the front line and sustained

very high casualties. Other units were subsequently fed into the front lines.

The 37th Torpedo Maintenance Unit was almost completely destroyed

when, with three times as many men as rifles, it entered the fighting at Shuri

and Yonabaru toward the end of May.

-

- The greatest misfortune affecting

the ultimate fate of the enemy naval forces occurred at the time of the mass

exodus from Shuri. The 32d Army headquarters directed all naval troops

to fall back on 28 May to a new defense area, near the coastal town of Nagusuku.

Because of an ambiguously worded order, the remaining men of the Base

Force destroyed most of the weapons and equipment which they were unable

to carry; they then moved south on 26 May, two days before they were scheduled

to withdraw. When they arrived at their assigned area they found it totally

unsuited to the type of fighting for which they were prepared, as well as

inferior to the area they had just left. Disgusted with their new sector,

the young officers asked Ota for permission to return to Oroku "to fight

and die at the place where we built positions and where we were so long to

die [sic] in that one part of the island which really belonged to the

Navy." Advocates of independent action by the Navy succeeded in persuading

Ota of the advisability of returning the troops to Oroku. Without consulting

the Army Ota ordered the troops back on 28 May, and the return was effected

that night. Naval troops numbering about 2,000 returned to their former positions.

Some Navy personnel stayed in the south to fight on the Yuza-Dake or Yaeju-Dake

line; the rest of the original 10,000 had been used up in the previous combat.

-

- Naha airfield, the largest and most

important which the Japanese had constructed on Okinawa, was at the northern

end of a strip of flat land on the

- [428]

-

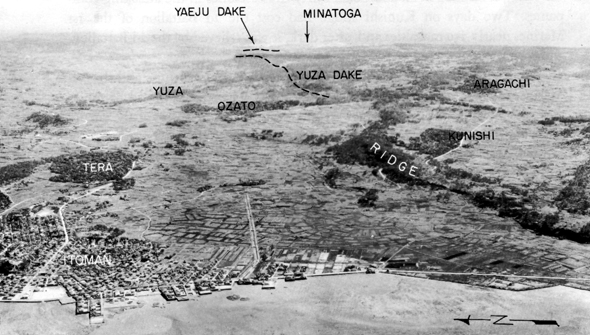

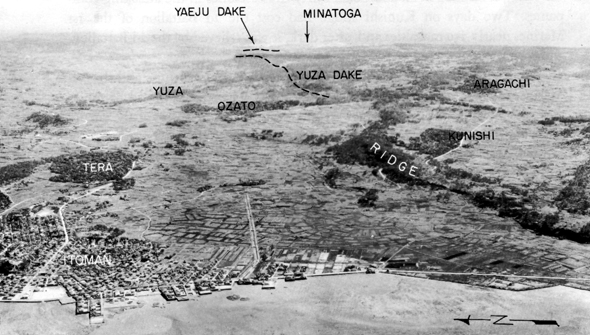

- ADVANCING TO YAEJU-DAKE through the Iwa area, American

tank passes burning native house, fired to lessen danger from snipers.

Below is seen a patrol of the 381st Infantry, 96 Division, moving south

toward Yaeju-Dake.

-

-

- [429]

-

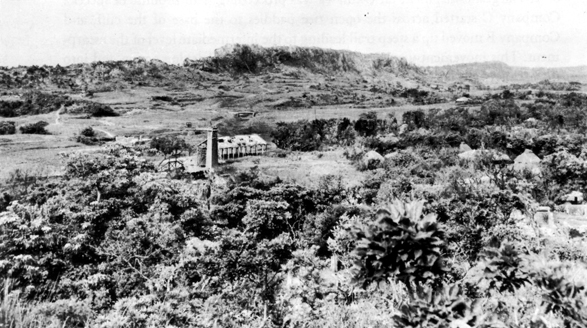

- LAST POINT OF RESISTANCE in the Oroku Peninsula

was Hill 57, shown above in panorama. Below is a close-up of a concrete

emplacement (dotted outline in photo above) after it had been blasted

open by Marine artillery fire.

-

-

- [430]

- west side of Oroku Peninsula. The

rest of the peninsula was wrinkled with ridges and hills up to 2000 feet in

height but was lacking in any pattern or dominant terrain features. Between

the hills were valleys planted in sugar cane and other dry crops; the valleys

had been sown with mines and were carefully covered by automatic weapons firing

from camouflaged cave openings.

-

- An Amphibious Assault

- A shore-to-shore movement would offer

suitable landing beaches and orient the American attack in the direction that

afforded the best use of supporting artillery. This plan of attacking from

the sea would also provide for supply by sea, made necessary by the break-down

of roads. Therefore General Shepherd, commander of the 6th Marine Division,

ordered the 4th Marines, followed by the 29th, to make a landing. Planning

and organization had been completed by the evening of 3 June. At 0445 on the

following morning supporting artillery began an hour-long preparation during

which 4,300 shells fell on the high ground in front of the landing beaches.

With amphibian tanks in the lead the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, embarked

from the assembly area north of the Asato River and headed south toward the

northern point of the Oroku Peninsula. The formation was partially broken

when some of the amphibian tractors, which had been used by the marines to

haul supplies to the front during the rainy period, failed after getting under

way, leaving elements of the assault force stranded in the water. There was

only light fire, however, when the first troops stepped ashore a few minutes

before o6oo and the men hurried inland to carve out a beachhead sufficiently

large to warrant landing the remainder of the force. An hour and a half after

the landing the two assault battalions were 900 yards inland, and twenty-four

tanks and four self-propelled guns were ashore; by 1000 the 29th Marines was

ordered to land and take up the north end of the division line. The landing

was proceeding satisfactorily.16

-

- As the 4th Marines landed on the north

point of Oroku the 6th Reconnaissance Company seized Ono-Yama, a small island

in the center of the Naha Inlet which formed the anchor for two destroyed

bridges linking Naha to the peninsula. A few defenders were killed, and the

island was in American hands an hour after the assault commenced. Replacement

of the bridges, necessary to provide adequate logistical support, was hindered

by Japanese machine-gun and 20-MM. shell fire, and it was not until the following

day that the final sections of a ponton bridge were floated into place.

- [431]

- Mud, Mines, and Machine Guns

- At the end of the first day assault

battalions, 1,800 yards beyond the point of the landing, faced stabilized

enemy fire power from a wealth of automatic weapons varying from light machine

guns to 40-mm. cannons. It was later learned that many of these weapons had

been stripped from damaged planes, adapted for use by ground troops, and,

with painstaking care, hidden underground behind narrow, camouflaged firing

ports that overlooked the mines own valleys and other approaches to the defended

hills. The 10-day battle for Oroku Peninsula is the story of a half-trained

enemy force, poor in standard weapons, organization, and hope of eventual

success, but possessed of abundant automatic fire power, a system of underground

positions larger than they could man, and a willingness to die in those positions

in order to make the Americans pay dearly for the ground.

-

- Gains were slowed down on the second

day and came to an abrupt halt when the 29th Marines, on the northern flank,

hit a hard core on Hill 57 near the center of the- peninsula. With progress

least difficult on the right (south), General Shepherd tried to crowd the

4th Marines forward to outflank the enemy's positions. The southern end of

the line yielded as far as the village of Gushi; then the entire line, 4,000

yards long, faced a tight ring of Japanese defenses that held the marines

to slight gains for two more days, 7 and 8 June. Use of tanks was restricted

by mud and the widely scattered mine fields, which were protected by abundant

machine-gun fire. Three platoons of tanks helped in the capture of Hill 57

on 7 June, but usually the tanks were bogged in mud or fenced off beyond direct-support

range by mine fields. In three instances when men from the 2d Battalion, 4th

Marines, were unable to fight their way to the top of a hill, they used the

extensive tunnel systems and went through the hills rather than over them.

-

- Meanwhile, the 1st Marine Division

had freed itself from the mud, and on 6 June it was halfway across the base

of Oroku Peninsula, closing the gap between the two corps but exposing its

own west flank. General Shepherd committed the Corps reserve, the 22d Marines,

sending them south to establish a line across the base of the peninsula. This

placed elements of the division on opposite sides of the Japanese troops on

Oroku, and General Shepherd, recognizing that the logical avenues of entry

to the Japanese hill positions were from the south and southeast, ordered

the 22d to patrol to the northwest and then to attack in that direction. The

4th Marines was ordered to attack on the left of the 22d's line.

- [432]

- With three regiments thus engaged

in the fight, the division continued to concentrate on an encircling move

to compress the Japanese on the high ground near Tomigusuki. There were no

soft spots along the enemy line, and each slow advance the marines scored

was against machine-gun and 20-MM. and 4o-mm. antiaircraft fire. Fighting

proceeded with the same sustained effort by both sides through 10 June, when

the remaining Japanese were confined in an area no larger than 1,000 by 2,000

yards. Subjected to extreme pressure, the Japanese during the night of 10

June erupted in a series of local counterattacks along the entire front. Two

hundred enemy dead were scattered along the front lines on the following morning.

-

- End o f the Okinawa Base Force

- General Shepherd struck back at the

Japanese at 0730, it June; he employed the greater part of eight battalions

and supported them with tanks, which after several days of clear weather were

no longer restricted by mud. This was planned as the final blow to break through

the enemy resistance. The 29th Marines attacking from the west, and the 4th

moving from the south, made only slight headway; the tad Marines, after an

intense artillery barrage, drove toward Hill 62 from the southeast. The first

attack stopped short of the objective, but, about noon, the 2d Battalion,

22d Marines, rammed another assault against Hill 62 while the 3d Battalion

moved off for Hill 53, about 300 yards north. The first of these objectives

fell by 1330, and Hill 53, which afforded observation of the remainder of

the enemy-held ground, soon afterward. The three regiments held a tight ring

in an area 1,000 yards square.

-

- A break-up in the Japanese forces

occurred on the following day. As the converging forces closed in on the remaining

pocket, the Japanese were forced from the high ground onto the flat land near

the Naha Inlet. Some chose to fight until killed; others, including several

who lay down on satchel charges and blew their bodies high in the air, destroyed

themselves. On 12 June and the day following, 159 surrendered-the first large

group of Japanese taken prisoner.

-

- When the destruction of his force

was nearly complete, Admiral Ota committed suicide. On 15 June, as patrols

sought out the last of the Japanese on Oroku, the marines found Ota's body

and those of five members of his staff lying on a raised, mattress-covered

platform in one of the passages in the underground headquarters. Their throats

had been cut, and, from the appearance of the room, it was apparent that an

aide had carefully arranged the bodies and tidied up after the self-destruction

of the Japanese officers. Nearly 200 other bodies were found in the headquarters,

one of the most elaborate underground systems on the

- [433]

- island. More than 1,500 feet of tunnels

connected the office rooms, which were well ventilated, equipped with electricity,

and reinforced with concrete doorways and walls.17

-

- The slow and tedious battle for Oroku

Peninsula had lasted for ten days. The total number of marines killed or wounded

was 2,608, a cost in casualties proportionately greater than the American

forces suffered during the fighting for Shuri, where they were opposed by

General Ushijima's infantrymen.

-

- Six days before the 6th Marine Division

wiped out Admiral Ota's force, and four days after the XXIV Corps separated

Chinen Peninsula from the rest of the battlefield, the 1st Marine Division

reached the west coast above Itoman. Besides straightening Tenth Army front

lines between that village and Gushichan, this advance opened a water supply

route for the advance elements of the III Amphibious Corps.18

-

-

- When the rainy period on Okinawa ended

on 5 June, troops of the XXIV Corps occupied a solid line across 6,000 yards

of soft clay. Supply was critical and was partially dependent upon air drops.

Tanks could not operate, and to the front, 1,000 or 1,500 yards away, stood

the craggy Yaeju-Dake and Yuza-Dake hill masses-physical barriers which, together

with Hill 95 on the east coast, formed a great wall across the entire XXIV

Corps sector from Gushichan to Yuza. The highest point of this 4-mile-long

cliff was the Yaeju-Dake Peak, which rose 290 feet above the adjoining valley

floor. Because of its shape the troops who fought up its slopes named it the

"Big Apple." The Yuza-Dake stood at the west end of the line and

then tapered off into Kunishi Ridge, which extended across the III Amphibious

Corps' sector. Hill 95, which paralleled rather than crossed the direction

of attack, formed the eastern anchor. On the seaward side of Hill 95 there

was a 300-foot drop to the water; on the side next to Hanagusuku village there

was another sheer drop of about 170 feet to the valley floor. The only break

in this defensive wall was in the 7th Division's sector, where a narrow valley

pointed south through Nakaza. This approach to the high tableland beyond the

escarpment cliff was subject to fire and observation from both flanks.

-

- Between this redoubtable terrain and

the front occupied by XXIV Corps on the evening of 5 June were a few grassy

knolls and numerous small hills scattered

- [434]

- BASE OF OROKU PENINSULA, where Okinawa Base Force made its

last stand.

-

- [435]

- over a generally flat valley. After

two weeks of almost continual rain, the valley was rich with verdure and thus

far only slightly torn by shells and combat.

-

- General Ushijima's army reached this

new defensive area several days ahead of the Americans and, by 3 or 4 June,

was deployed in the caves and crevices in and behind the escarpment wall.

The combined strength of 32d Army infantry units was about 1 1,000

men. Total enemy strength, however, amounted to nearly three times that number.

It included personnel from artillery or mortar units which no longer possessed

weapons; signal, ordnance, airfield construction, and other units whose normal

duties were no longer necessary; and conscripted Okinawans whose ability and

will to fight did not equal those of the regular Japanese soldiers.19

-

- About 8,000 men made up the Japanese

24th Division, which, as his strongest unit, General Ushijima stationed

in the center and across the west flank from Yaeju-Dake to the town of Itoman.

The 62d Division, originally the 32d Army's best but now reduced

to two or three thousand men, took up reserve positions near Makabe. This

left only the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade to defend the eastern

part of the enemy's final line facing the 7th Division. Around these three

original major combat units General Ushijima grouped the remaining service

and labor troops, scattered naval personnel, and Okinawan conscripts. Thus,

with a heterogenous army lacking in adequate training, artillery support,

communications, and equipment and supplies, General Ushijima waited for the

final battle. His headquarters took only a 20-day supply of rations when it

moved from Shuri to the southern tip of the island-an indication of his own

appraisal of his army's capabilities.

-

- Both sides watched warily and prepared

for the Americans' next assault. The state of supply, the condition of the

narrow roads linking assault elements with supply dumps at Yonabaru, and the

lack of armored and direct-fire weapons prevented an immediate large-scale

attack by the XXIV Corps. American commanders probed the enemy line with patrols,

regrouped their forces, and assembled necessary supplies through the little

port of Minatoga, which was in operation by 8 June.20

- [436]

- YAEJU-DAKE was brought under American artillery fire shortly before

the infantry attempted its first advance to the escarpment. Burst at upper

left is white phosphorus.

-

- HILL 95, near Yaeju-Dake, with Gushichan in foreground

-

- [437]

- Locating Enemy Strength

- One of these probing actions made

a slight penetration of the enemy's line and soon revealed the nature and

volume of the enemy fire power protecting the final Japanese line. Nearest

the Big Apple Peak was the 381st Infantry, first to venture into the Yaeju-Dake

and the first to be driven back. West of the Big Apple was a secondary escarpment,

like a step, about halfway to the top. Col. Michael E. Halloran ordered the

1st Battalion to explore this area and, if possible, to seize a lodgment on

the lower part of the escarpment which would permit an attack against the

Big Apple from the west and against the flank of the enemy's most dominating

fortification.21

-

- On the morning of 6 June the battalion

commander, Maj. V. H. Thompson, leapfrogged his companies through Yunagusuku

against only half-hearted opposition and then sent Company B, under Capt.

John E. Byers, forward to test the escarpment wall. Three squad-sized patrols

crept through bands of fire from machine guns, some of which were so far inside

caves that they could not be destroyed with grenades, and reached the lower

of the two escarpments. The rest of the company followed, and Thompson ordered

Company C to move abreast and left of Byers' men. It was midafternoon, and

the first attempt at penetration of this largest escarpment on Okinawa was

proceeding with promise of success. Company C started across the open rice

paddies to the base of the cliff, and Company B moved up a steep trail leading

to the intermediate level of the escarpment. This movement went beyond the

line of enemy delaying action and into the area where General Ushijima had

ordered his army to "bring all its might to bear" to break up the

American attack and exact a heavy toll of the attacking force. "To this

end," he instructed, "the present position will be defended to the

death, even to the last man. Needless to say, retreat is forbidden."

22

-

- The Japanese waited patiently until

both companies were in a belt of pre-registered fire, then opened up with

machine guns and 20-min. dual purpose guns in sufficient quantity to lace

both companies with beads of automatic fire. Major Thompson immediately started

to organize a withdrawal and employed ten battalions of artillery to drop

smoke shells in front of his trapped men. Even this was inadequate and many

of the troops did not return until after dark. Company C lost five men killed

and as many wounded. Casualties in Company B for the day totaled 43, including

14 missing. Of the missing men, 4 were dead,

- [438]

- 2 returned the following morning,

and the other 8 were trapped behind enemy lines. Three of the trapped men

were subsequently killed by friendly or enemy fire, and the remaining five

stayed in enemy territory until the morning of 14 June, although they tried

to escape on each of the eight intervening nights.

-

- For the next three days the 96th Division

blasted the coral escarpment with artillery and air strikes and watched it

closely for possible gun positions and strong points. The heaviest fighting

occurred on the extreme eastern flank of the 7th Division, where Company B,

184th Infantry, faced unyielding opposition on a tapered ridge that pointed

northeast from the tip of Hill 95. One of the roughest single terrain features

on Okinawa, this 800-yard-long ridge was a jumbled mass of coral that was

as porous as sponge and as brittle and sharp as glass. There were several

fortified positions on the ridge as well as numerous cavities which protected

individual enemy riflemen. The entire ridge was also under fire and observation

from other positions on Hill 95. The advance was tedious, and the company

made only slight progress. The largest gain from 6 to 9 June was in the zone

of the 17th Infantry, which forced advances up to 1,800 yards and occupied

the green knolls at the base of the escarpment. These small hills were not

heavily defended but they were exposed to enemy fire from the face of the

Yaeju-Dake and from the tableland above.23

-

- The 32d Infantry, which had rounded

up about 20,000 Okinawa civilians during six days of patrol activity on Chinen

Peninsula, moved south on the afternoon of 8 May and effected relief of the

184th. Road conditions were improved and a large quantity of supplies reached

Minatoga on 8 June; two companies of medium tanks were near the front lines

and others were moving forward. General Arnold planned to strike the first

blow against the new Japanese line and ordered the attack to commence at 0730

on 9 June. There were two immediate objectives. The task of reducing Hill

95 and the rough-hewn coral ridge that lay in front fell to the 1st Battalion,

32d Infantry, commanded by Lt. Col. Robert C. Foulston; the 3d Battalion,

17th Infantry, under Lt. Col Lee Wallace, was to secure a lodgment on the

southern and low end of the Yaeju Dake at a point just north of the town of

Asato.

-

- First Break in the Japanese Wall

- Dawn patrols proceeded unmolested

toward the coral ridge in front of Hill 95, but the Japanese reacted quickly

before the remainder of Company C of the 32d Infantry, which carried the burden

of the attack, had moved 100 yards.

- [439]

- As long as the men kept their heads

down the enemy fire subsided, but any attempt to move forward attracted rifle

and machine-gun and knee-mortar fire which blasted sharp chips from the coral

formation. The company commander, Capt. Robert Washnok, held up the frontal

assault, placed artillery shells on Hill 95, used about 2,000 mortar shells

on his objective, and then tried working a platoon forward on the Gushichan

side to eliminate two strongly defended knobs near the end of Hill 95. This

effort was partially successful; the men killed thirteen Japanese and located

the source of the most troublesome automatic fire, but toward evening they

had to be recalled.

-

- The first and greatest obstacle confronting

Wallace's attack was the open ground over which both assault companies had

to move. Wallace used all available support and the men camouflaged themselves

with grass and rice plants, but enemy fire began almost as soon as the leading

platoons moved into the open. The infantrymen crawled through the slimy rice

paddies on their stomachs. Within an hour Company I was strung from the line

of departure to the base of the objective which two squads had reached. About

this time the Japanese opened fire with another machine gun, separating the

advance squads with a band of fire. This left one squad to continue the attack;

the remainder of the company was unable to move, cut off by fire or strung

across the rice paddies.

-

- Those men in the squad still free

to operate lifted and pulled each other to the edge of the cliff and crawled

quietly forward through the high grass on top. Pfc. Ignac A. Zeleski, a BAR

man, moved so stealthily that he almost touched the heels of one Japanese.

Zeleski killed him, and the other men killed eight more Japanese within the

first ten minutes. Another squad reached the top of the escarpment about an

hour later but was caught in cross and grazing fire from three machine guns,

and the entire 8-man squad was killed. Gradually, however, a few more men

reached the top, and by evening there were twenty men from Company I holding

a small area at the escarpment rim.

-

- Company K had a similar experience.

Accurate enemy fire killed one man, wounded two others, and halted the company

when it was from 200 to 300 yards from its objective. For forty-five minutes

the attack dragged on until S/Sgt. Lester L. Johnson and eight men maneuvered

forward through enemy fire, gained the high ground, and concentrated their

fire on the enemy machine gun that was firing on the remainder of the company.

This did not silence the gun but did prevent the gunner from aiming well,

and Johnson waved for the rest of the company to follow. By 1330 of 9 June

Company K was consolidated on the southeastern tip of the Yaeju-Dake. That

evening, three small but deter-

- [440]

- mined counterattacks, with sustained

grenade fire between each attempt, hit the small force from Company I, which

held off the attackers with a light machine gun and automatic rifles.

-

- Tanks stirred dust along the narrow

roads when, at 0600 on the morning of 10 June, they started for the front

lines. A full battalion was on hand to support the 7th Division; two companies

operated with the 96th Division, which began its assault on the Yaeju-Dake

that morning. The character of warfare on Okinawa changed, and until the end

of the campaign there was a freer, more aggressive use of tanks. Weather and

terrain were more favorable, and flame tanks became the American solution

to the Japanese coral caves; interference from enemy shells became less with

the destruction of each Japanese gun; and, more important, through experience

the infantrymen and tankers developed a team that neared perfection. Improved

visibility also aided observation of artillery fire and air strikes. The battle

for the southern tip of Okinawa blazed with orange rods of flame and became

a thunderous roar of machine guns, shells, rockets, and bombs.24

-

- Pumping Flame Through a Hose

- Company C, 32d Infantry, still bore

the responsibility of destroying the Japanese in front of Hill 95. When the

fighting flared again on the second day of the attack, Navy cruisers fired

on the seaward side of the ridge; artillery and tanks shelled and machine-gunned

the top and sides of Hill 95; and the ad Battalion attacked toward the village

of Hanagusuku. Captain Washnok and his men crept cautiously over the coral.

The Japanese did not withdraw; Company C killed them as it advanced. By early

afternoon the men had eliminated all enemy fire except that from a few scattered

rifles and several fortified caves in two rocky knobs near the northeast end

of Hill 95. Colonel Finn advocated the use of flame. Washnok held his company

in place, and Capt. Tony Niemeyer, 6-foot 4-inch commander of Company C, 713th

Armored Flame Thrower Battalion, moved one tank to the base of the two knobs.

Then he attached a 200-foot hose, a special piece of equipment for delivering

fuel to an area inaccessible to the tank. S/Sgt. Joseph Frydrych, infantry

platoon leader, Captain Niemeyer, and Sgt. Paul E. Schrum dragged the hose

onto the high rock and sprayed napalm over the two strong points, forcing

out thirty-five or forty enemy soldiers whom the infantryman killed by rifle

or BAR fire. Except for stray rifle fire, all enemy opposition in the coral

ridge was gone when the 1st Battalion set up

- [441]

- defenses for the night. The Japanese

came back, however, during the night; they harassed Company C with mortars

and grenades and prowled in the open in front of the other advanced companies.

Two days of fighting through the rough terrain had cost Company C forty-three

casualties, ten of whom were killed.

-

- Niemeyer was active again on the morning

of 11 June, when the 32d Infantry proceeded against the high end of Hill 95.

Company B had taken the lead and pushed against the northeast end of the hill;

although tank and artillery fire on Hill 95 was so heavy that the hill was

partially obscured with haze, several machine guns fired from caves which

could not be reached, and the men were temporarily stopped. When this approach

failed, Niemeyer, Colonel Finn, and Capt. Dallas D. Thomas, Company B commander,

decided to use the flamethrower tanks to burn a path to the top of the 170-foot

coral cliff. Captain Niemeyer, a daring soldier who was enthusiastic over

the, capabilities of his flamethrower tanks, moved them to the Hanagusuku

side of Hill 95 and forced streams of red flame against the portion of the

cliff where the infantrymen expected to make the ascent. This flame eliminated

any threat of close-quarters resistance from caves in the face of the escarpment.

The next step was to reach the flat top of the hill and secure a toe hold

on the high ground. At 1100 Niemeyer and a platoon under 1st Lt. Frank A.

Davis fastened one end of a hose to a flame tank and began dragging the other

end up the almost vertical side of the hill. The tanks, artillery, mortars,

and machine guns stepped up their rate of fire to keep down enemy interference,

the men being as exposed as spiders on a bare wall. This spectacular attack

was also slow, and it was forty-five minutes before the men reached a small

shelf just below the lip of the escarpment. They stopped here long enough

to squirt napalm onto the flat rocks above them in case any Japanese were

waiting for them there, then scrambled over the edge and poured flame onto

the near-by area. Davis and his men fanned out behind the flame. The remainder

of Company B followed immediately; the company quickly expanded its holding

across the northeast end of the hill and then pushed south, still using flame

against suspected enemy strong points. When the fuel from one tank was exhausted

the hose was fitted to another tank.

-

- Colonel Foulston reinforced his attacking

company with two platoons from Company A. When evening came the 1st Battalion

had destroyed the enemy force on the northeast end of the tableland. The men

were involved in close-in fighting with Japanese hiding in rocks and crevices

but their grip on the tableland was firm.

- [442]

- When it was time for front-line troops

to dig in on the evening of 11 June, one battalion from each of the 7th Division's

attacking regiments held a small corner of the enemy's main line on southern

Okinawa. During the three days since the assault against Hill 95 and the Yaeju-Dake

began on 9 June, the right (western) end of the XXIV Corps line had remained

relatively unchanged. The 1st Battalion, 17th Infantry, softened its end of

the Yaeju-Dake with lavish use of artillery, to destroy enemy strong points

on the plateau above the escarpment, and employed tanks and cannon company

weapons directly against caves in the face of the cliff. 25

-

- The 96th Attacks in the Center

- Meanwhile, the 38rst and 383d Infantry

Regiments hammered away at the high peaks of Yaeju-Dake and Yuza-Dake. On

10 June the 383d attacked toward the town of Yuza, which it reached the following

day. There was heavy fighting from one wall to the next in the battered town

and, in addition, constant fire from Yuza-Dake, which towered over the southern

edge of the town. The troops withdrew that evening when enemy fire increased.26

-

- With its approach blocked by the highest

and steepest section of the YaejuDake wall, the 381st Infantry struck toward

the saddle between the Big Apple Peak and the Yuza-Dake, where the escarpment

rose in two levels. Major Thompson's 1st Battalion had unsuccessfully explored

this route on 6 June when Companies B and C reached the intermediate level,

immediately drew pre-registered fire, and were forced to abandon their gains

under smoke. After shelling the Japanese emplacements for four days these

two companies attacked over the same route, this time with tank support. Difficult

terrain and mines prevented effective use of the tanks, but Companies B and

C pushed ahead without them and, by 0900 of 10 June, three of the attacking

platoons were back on the ledge where the previous attack had stalled. Japanese

machine guns opened fire as promptly and accurately as before, and the advance

again ended suddenly with half of the men on the first ledge of the escarpment

and the rest scattered in the rice paddies to the rear.

-

- Throughout the day the company commanders

tried to maneuver the trailing elements of their units forward. Each effort

failed until, late in the afternoon, another smoke screen was laid down, this

time to cover the advance of the rear elements and the preparation of defensive

positions for the night. When the smoke had cleared, both companies were in

place. A few minutes later about a

- [443]

Flame-throwing tanks advance to Hill 95.

|

Flame hose is stretched up the hill.

|

Flame from hose hits hill.

|

Burned, bewildered survivor is captured

|

Enemy positions burned out by Capt. Tony Niemeyer's team.

|

- FLAME THROUGH A HOSE

-

- [444]

- hundred Japanese troops, believing

the smoke had covered a withdrawal as on 6 June, emerged from their holes

and gathered near a building at the southern end of the flat area, where they

began to change to civilian clothes for their customary night infiltrations.

Capt. Philip D. Newell, commanding Company C., adjusted artillery fire in

their midst and most of them were killed.

-

- An ammunition-carrying party took

supplies to the forward companies that night, enabling the men to defend their

gain successfully against a counterattack that came early the next morning.

Just before dawn on 11 June the remainder of the battalion joined the two

advance companies. The 381st Infantry made no attempt to extend its holdings

on 11 June but conducted heavy tank and artillery fire against the cave openings

on the Big Apple Peak. The next important thrust against the Japanese line

was to occur in the sector of the 17th Infantry where Col. Francis Pachler

was planning a night attack against his portion of the Yaeju-Dake.

-

- Night Move Onto the Yaeju-Dake

- Colonel Pachler had good reasons for

favoring a night move. The advantages of observation belonged almost completely

to the defending force, and this had seriously interfered when the 3d Battalion,

Uth Infantry, seized the southeast end of the escarpment. The coral wall of

the escarpment in front of the 1st Battalion was higher at this end; at the

same time the two suitable routes leading to the high ground were narrow and

could be easily controlled by Japanese fire. The troops had held positions

at the base of the 170-foot cliff for several days and were familiar with

the terrain. They had, in fact, been looking at the escarpment so long that,

as their commander, Maj. Maynard Weaver, said, they were anxious to get on

top so that they could look at something else.27

-

- Although the night attack was planned

principally for the 1st Battalion, Colonel Pachler also decided on a coordinated

move to enlarge the area held by the 3d Battalion. The final plan included

three assault companies: Company A was to occupy a cluster of coral about

a hundred yards beyond the edge of the escarpment and next to the boundary

between the 7th and 96th Divisions; Company B had a similar objective about

200 yards to the southeast; and Company L was directed against the small hill

between the 1st Battalion's objectives and the positions occupied by the 3d

Battalion on ii June. Each company was to take a separate route. Company A's

path led directly up the face of the cliff to its objective. Company B had

to travel south to a break in

- [445]

- the escarpment face and then, once

on the high ground, turn right toward its objective. The objective of Company

L was near the edge of the escarpment and easily approached.

-

- Movement was to begin at 0400 on 12

June. Since the attack was based on stealth, no artillery preparation was

used. However, 2 battalions of 105-mmartillery, 1 battery of 155-mm. howitzers,

and an 8-inch howitzer battalion were scheduled to deliver heavy harassing

fires during the early part of the night. Also a total of 21 batteries registered

their fires on the afternoon of 11 June and were prepared to surround the

objectives with protective artillery fire if trouble developed after they

were reached. One section of heavy machine guns was attached to each assault

company.

-

- Colonel Pachler had planned the attack

carefully and insisted that every man participating know all details of the

movement. Reconnaissance patrols had examined the trails leading to the high

ground, and demolition teams had satchel-charged known cave positions in the

face of the cliff. Nevertheless, everyone concerned with the attack dreaded

the possibility of confusion that might result from the unknown conditions

during darkness. This apprehension increased at 2000 on the night of 11 June

when the 7th Division G-2 Section reported interception of an enemy radio

message that evening which said, "Prepare to support the attack at 2300."

A little later another intercepted message read: "If there are any volunteers

for the suicide penetration, report them before the contact which is to be

made one hour from now." 28

At the same time, from dusk until nearly 2300, the Japanese fired an extremely

heavy concentration of artillery which front-line troops fully expected to

be followed by a counterattack. The counterattack came but was aimed against

the 1st Battalion, 32d Infantry, which had reached the top of Hill 95 that

afternoon, and against the 96th Division. There was no enemy activity in the

17th Infantry's sector.

-

- Night illumination and harassing shell

fire ceased shortly before 0400, and thereafter the execution of the attack

followed the plan almost without variation. The attacking companies moved

out in single file. As promptly as if it had been scheduled, a heavy fog settled

over southern Okinawa. It was of the right density-allowing visibility up

to ten feet-to provide concealment but still allow the men to follow their

paths without confusion. On the high ground Company A found a few civilians

wandering about, and the leading platoon of Company B met three Japanese soldiers

just after it reached the shelf of the

- [446]

- escarpment. The men ignored them and

walked quietly on. Nor did the enemy open fire. By 0530, a few minutes after

dawn, Companies A and B were in place and no one had fired a shot. (See Map

No. XLVIII.)

-

- Without incident Company L reached

its objective and then, anxious to take advantage of the fog and the absence

of enemy fire, its commander sent his support platoon to another small hill

fifty yards beyond. This objective was secured within a few minutes, after

two enemy soldiers were killed. The platoon leader called his company commander

to report progress and then frantically called for mortar fire. Walking toward

his position in a column of twos were about fifty Japanese. The Americans

opened fire with rifles and BAR's, broke up the column formation, and counted

thirty-seven enemy soldiers killed; the others escaped.

-

- Men in the 1st Battalion were pleased

no less with the success of the night attack. A few minutes after Company

A was in place, four enemy soldiers came trudging up toward them. They were

killed with as many shots. Four others followed these at a short interval

and were killed in the same way. Company B was not molested until about 0530,

when some Japanese tried to come out of several caves in the center of the

company's position. Since the cave openings were reinforced with concrete

they could not be closed with demolition charges, but the men guarded the

entrances and shot the Japanese as they emerged. Soon after daylight Company

C began mopping up caves in the face of the escarpment, and later it joined

the rest of the battalion on the high ground. By 0800 the situation was settled

and the 17th Infantry held strong positions on the Yaeju-Dake. The Japanese

had withdrawn their front-line troops from Yaeju-Dake during the night in

order to escape harassing artillery, but they had expected to reoccupy it

before "the expected 0700 attack." Fifteen hours after the 32d Infantry

burned its way to the top of Hill 95, the 17th Infantry had seized its portion

of the Yaeju-Dake in a masterfully executed night attack.

-

- The 2d Battalion, 17th Infantry, relieved

Companies I and K during the day, and, with Company L attached and supported

by medium and flame tanks, continued the attack. The 1st Battalion held its

ground and fired at enemy soldiers who, slow to realize that their defensive

terrain had been stolen during the night, tried to creep back to their posts.

Company B alone killed sixty-three during the day.

-

- Progress in the Center

- At 0600 on the same day, 12 June,

Colonel Holloran's 381st Infantry delivered the next blow against the Japanese

main line of resistance. Since 10 June,

- [447]

-

- NIGHT ATTACK ON YAEJU-DAKE by the 17th Infantry,

7th Division, on 12 June resulted in capture of the section shown in picture

above. Company A went up the path shown near center and occupied the coral

ridges appearing in center. Company B moved up the slope at left and swung

back to right on top of the escarpment. Below are infantrymen on Yaeju-Dake

the morning of 13 June. Litter team evacuating wounded can be seen on

the road

-

-

- [448]

- when the 381st launched its attack

against the escarpment, the 1st Battalion had gained a toe hold on the intermediate

level in the saddle between the Yaeju-Dake and the Yuza-Dake Peaks. The 3d

Battalion had cleaned the enemy troops out of Tomui but was unable to proceed

against the blunt and steep segment of the escarpment that lay in its zone.

For 12 June Colonel Halloran committed his reserve battalion, the 2d, on the

west end of his flank to fight abreast of the center salient and, at the same

time, close a gap between his regiment and the 383d. Then, depending upon

the success of the 17th Infantry's night attack, the 3d Battalion was to press

its attack against the adjoining portion of the escarpment.29

-

- Despite extensive use of artillery

and tanks on previous days to batter cave openings in the face of the cliff,

enemy fire flared as briskly as ever when the 3d Battalion, under Lt. Col.

D. A. Nolan, Jr., reached the base of the escarpment on the morning of 12

June. Realizing that a frontal assault against this defended wall would be

both slow and costly, Colonel Nolan left Company K to contain the enemy and

to mop up near the bottom of the cliff; he ordered Capt. Roy A. Davis to take

Company L around to the southeast, climb the escarpment in the 7th Division's

zone, and then move back along the edge of the cliff to a position above Company

K.30

-

- It was nearly midafternoon before

Davis and his men were in place on the high ground. Company K, meanwhile,

worked along the base of the cliff under a steady volume of rifle fire but

with protection of smoke. An effort to join the two elements of the battalion

for the night failed, but the 381st Infantry had broken a 3-day stalemate

at the steepest part of the escarpment and was now ready to pry the next section

from Japanese control.

-

- Japanese troops still controlled the

Big Apple Peak, which rose about sixty feet above the general level of the

plateau, but by evening of 12 June the 7th and 96th Divisions had forced the

reconstituted 44th Independent Mixed Brigade from the southeastern

end of the enemy's line.

-

- General Ushijima acted as quickly

as his shattered communication system and the confusion of his front-line

units would permit. With his artillery pieces shelled and bombed into near-silence,

and his supplies and equipment diminishing even faster than his manpower,

his only hope was to send more troops into the shell fire and flame with which

the American forces were sweeping the front-line area. His order read:

- [449]

- The enemy in the 44th IMB sector has

finally penetrated our main line of resistance . . . . The plan of the 44th

IMB is to annihilate, with its main strength, the enemy penetrating the Yaeju-Dake

sector.

-

- The Army will undertake to reoccupy

and hold its Main Line of Resistance to the death. The 62d Division will place

two picked infantry battalions under the command of the CG, 44th IMB.31

-

- The 64th Brigade-the part

of the 62d Division which had moved from Shuri to reserve positions

near Makabe-did not issue this order until late on 13 June, fully thirty hours

after its need arose. Moreover, piecemeal commitment of reserve troops was

inadequate. By 13 June the 44th Brigade was so close to destruction

that when the reinforcements arrived the remnants of the 44th were

absorbed by the reinforcing battalions and there were still not enough men

to hold the line. The enemy then committed the main strength of the 62d

Division, his last reserve and hope, with a plea for cooperation and orders

to "reoccupy and secure the Main Line of Resistance."

-

- By the time the 62d Division

could move onto the line, however, it ran squarely into General Hodge's men

attacking south across the coral-studded plateau. The Americans were moving

behind the fire of machine guns and tanks and over the bodies of the Japanese

who had defended their last strong line "to the death."

-

- The Battle of Kunishi Ridge

- Only the eastern end of the Japanese

line collapsed. On the western side of the island troops of the 24th Division

fought to a standstill one regiment of the 96th Division and the 1st Marine

Division from is until 17 June. This slugging battle of tanks and infantrymen,

with heavy blows furnished by planes and by naval and ground artillery, was

for the possession of Yuza Peak and Kunishi Ridge. Yuza Peak, approximately

300 feet higher than the surrounding ground, dominated this part of the fortified

line and was the source of most of the enemy fire. Its capture was the responsibility

of the 383d Infantry, 96th Division. The western side of Yuza Peak tapered

off toward the sea and formed Kunishi Ridge, a 2,000-yard-long coral barrier

lying athwart the 1st Marine Division sector. Movement toward the Peak was

restricted by extensive mine fields.

-

- On three successive days the 383d

Infantry drove the enemy troops from the town of Yuza, but each time machine-gun

fire plunging from the coral peak beyond forced the men to withdraw to defensive

positions at night. The Japanese reoccupied the town each night. Real progress

was first made on 15 June when

- [450]

- the 2d Battalion, 382d Infantry, having

relieved the center battalion of the 3834, gained the northern slope of the

peak. The remainder of the 383d, weary from thirty-five days of continuous

combat, passed into reserve on the following day, and Colonel Dill's 382d

Infantry proceeded against the hard core of the Yuza line.32

-

- Kunishi Ridge was the scene of the

most frantic, bewildering, and costly close-in battle on the southern tip

of Okinawa. After reaching the west coast of the island above Itoman and isolating

Oroku Peninsula from the rest of the southern battlefield, the 1st Marine

Division edged forward against slight resistance until the front lines were

1,500 yards north of Kunishi Ridge and subject to fire and observation from

the heights of Yuza Peak. Two regiments, the 1st and 7th, were abreast. The

1st Marines, on the left, were the first to go beyond the guarded approaches

of the Japanese line and the first to pay heavily with casualties. On 10 June

the 1st Battalion lost 125 men wounded or killed during an attack against

a small hill west of Yuza town. Seventy-five of these were from Company C.

On the same day the 7th Marines reached the high ground at the northern edge

of Tera, a long ridge contested almost as vigorously. The left flank swung

ahead again on 11 June to Hill 69, west of Ozato, against steady and heavy

opposition.33

-

- A 1,000-yard strip of low and generally

level ground separated the 1st Marine Division's line between Tera and Ozato

from Kunishi Ridge, the next step in the advance. The 7th Marines ventured

onto this open ground on 11 June and was promptly driven back by Japanese

machine guns which covered the entire valley. As a result of this experience,

General del Valle and the commander of the 7th Marines, Col. Edward W. Snedeker,

decided to make the next move under cover of darkness. Each of the assault

battalions was to lead off with one company at 0300 on12 June, seize the west

end of Kunishi Ridge and hold until daylight, and then support the advance

of the remainder of the battalions.

-

- Companies C and F walked onto the

ridge with surprising ease, but the illusion of easy victory ended at dawn.

Company C opened fire first, killing several enemy soldiers just as the two

companies reached their objectives. This disturbance was the signal for immediate

enemy action. Mortar shells began falling within a minute or two, and, as

daylight increased, the Japanese sighted

- [451]

- their guns along the length of the

coral ridge and began shelling and machine-gunning the valley of approach

to prevent reinforcement. Colonel Snedeker challenged the enemy guns with

two tanks, but one of these was knocked out and the other driven back by the

fury of the shell fire. Both forward companies were suffering casualties and

asked for help, but the other companies of the two battalions could no more

move across the valley with impunity than the assault companies could expose

themselves on Kunishi Ridge.

-

- An attempt to cross under smoke failed

when the Japanese crisscrossed bands of machine-gun fire through the haze

and forced the two companies and their tank support to withdraw. In the afternoon,

with Companies C and F still asking for help, several tanks succeeded in reaching

Kunishi Ridge with a supply of plasma, water, and ammunition and brought back

the seriously wounded. After this successful venture the battalion commanders

evolved a plan for ferrying infantrymen, six in each tank, across the 1,000-yard

strip of exposed ground. Before nightfall fifty-four men had dropped through

the tank escape hatches onto Kunishi Ridge, and twenty-two casualties were

evacuated on the return trips. This method of transporting both supplies and

men was used throughout the fighting for Kunishi Ridge. 34

-

- The difficulties of 12 June were only

the beginning of trouble. With the return of daylight on 13 June six companies

occupied the lower end of Kunishi Ridge, and none of them could move. All

were dependent upon tanks for supplies and evacuation. Twenty-nine planes

dropped supplies, but with only partial success since a portion of the drops

fell beyond reach and was unrecoverable. One hundred and forty men from the

two battalions were casualties on 13 June; the seriously wounded were returned

in tanks, men with light wounds stayed on the ridge, and the bodies of the

dead were gathered near the base of the ridge.

-

- The burden of offensive action fell

upon the tanks on 13 June and the three days following. Flame and medium tanks

moving out on firing missions carried supplies and reinforcements forward

and then, on the return trip for more fuel or ammunition, carried wounded

men to the rear. Soft rice paddies made it necessary for the tanks to stay

on the one good road in the sector, and this road was effectively covered

by Japanese 47-mm. shells and other artillery, which destroyed or damaged

a total of twenty-one tanks during the 5-day battle.

- [452]

- YUZA PEAK, under attack by the 382d Infantry, 96th Division. Tanks

are working on the caves and tunnel system at base ridge of ridge.

-

- KUNISHI RIDGE, with Yuza-Dake and Yaeju-Dake Escarpments in background.

From the ridge the enemy fired on troops attacking Yuza peak. (photo taken

10 October 1944.)

-

- [453]

- Most enemy fire on Kunishi Ridge came

from the front and the left flank. To relieve this pressure from the left,

the 1st Marines ordered the 2d Battalion to seize the eastern and higher end

to the left of the 7th Marines. This attack was similar to the first both

in plan and in result. At 0300 on 14 June Companies E and G moved out. Two

hours later the assault platoons were in place, but at dawn a sudden heavy

volume of enemy fire interrupted further advance. The leading men were cut

off, the rear elements could not move, and all the men were receiving rifle,

mortar, and machine-gun fire from the front and left flank and rifle fire

from bypassed Japanese in the rear. No one could stand up on the ridge, and

even the wounded had to be dragged on ponchos to the escape hatch underneath

the tanks upon which, as did also the 7th Marines, these two companies depended

for supply and evacuation. It was not until dark that the battalion was able

to consolidate its position.

-

- The two regiments held grimly to Kunishi

Ridge although making no appreciable gains until 17 June, after the tanks,

planes, and artillery had destroyed the enemy's ability and will to resist.

The 7th Marines attempted to expand their hold on 15 June but, although fifteen

battalions of artillery supported the effort, it resulted in an additional

thirty-five casualties in the attaching companies. Two days on Kunishi Ridge

had cost the 2d Battalion of the 1st Marines nearly 150 casualties and, after

dark, it was relieved by the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines.

-

- Signs of weakening enemy strength

appeared first on 16 June and the 7th Marines made some headway on each of

its flanks. The zone of the 2d Battalion was taken over by the 22d Marines

before dawn of the 17th. Most of the enemy resistance disappeared when these

comparatively fresh troops took up the attack and gained ground on 17 June.

During the five days of savage fighting, tanks had carried 550 reinforcing

troops and approximately 90 tons of supplies to Kunishi Ridge and had evacuated

1,150 troops to the rear, most of

- whom were casualties.

- [454]

page created 10 December 2001