Chapter X:

QUADRANT - Shaping the Patterns: August 1943

As the QUADRANT Conference drew near, General Marshall and his staff were

convinced of the need for a showdown with the British. Once before-in July

1942-Marshall had led a move for a showdown. Then he had had to yield on a

cross-Channel operation and accept TORCH instead. A series of

opportunistic moves had followed in the Mediterranean-moves the U.S.

staff sought to parallel with limited offensive actions in the Pacific.

Marshall had fought to keep the Mediterranean commitments limited while he

struggled to keep the BOLERO idea alive and the war against Japan

progressing. But there was always the danger that the two limited

wars-one in the Pacific, the other in the Mediterranean-would become

all-out wars or absorb so much that little would be left for a major

offensive in northwest Europe. The Army planners now feared that the

Mediterranean trend had already gone so far as to be well-nigh

irreversible. There were also signs, as Marshall was aware, of increasing

restlessness among Navy planners, anxious to get on with the Pacific war,

over his European strategy. At hand was an acceptable plan for

concentration in the United Kingdom for a cross-Channel operation-Plan

OVERLORD. The time for

a final decision on European strategy therefore appeared to Marshall to

have arrived. But would the President now support him, and, if so, would

they be able to convince the Prime Minister and his staff?

Staff Planning

and the President's

Position

Part of the answer was soon to come. General Marshall, on the eve of his

departure for Quebec, met with the President at the White House to

discuss the line of action to be followed at QUADRANT. At this meeting on

9 August, the President observed that the planners were "always

conservative and saw all the difficulties," and that more could usually be

accomplished than they would admit. Between OVERLORD and post-HUSKY

operations in the Mediterranean (now called PRICELESS), he assured the

Army Chief of Staff that he was insistent on OVERLORD. But he felt that

more could be done in the Mediterranean than was currently proposed by the

U. S. planners. Pointing to the scheduled departure of seasoned troops from

the Mediterranean to the United Kingdom, he agreed that the seven

battle-tested

[211]

divisions be provided for OVERLORD. He proposed, however, that seven fresh

divisions be dispatched from the United States for PRICELESS. At the same

time the President assured Marshall that he did not wish to have anything

to do with an operation into the Balkans nor did he even intend to agree

to a British expedition in that area that would cost the United States

vital resources such as ships and landing craft necessary for other

operations. He was in favor of securing a position in Italy to the north

of Rome and taking Sardinia and Corsica, thereby posing a serious threat

to southern France.

General Marshall replied that the United States "had strained programmed

resources well to the limit" in the agreements already reached regarding

OVERLORD and PRICELESS. While the movement of three divisions from

PRICELESS forces to OVERLORD could be undertaken without a loss in troop

lift and with some advantage in equipping the French, beyond this point

movements to OVERLORD of veteran units would cost the United States part

of its troop lift. Marshall feared that the proposed movement from the

United States to PRICELESS would result in a corresponding reduction for

OVERLORD. He promised the President, however, that he would have a

critical review made of the logistical factors involved. In a humorous

vein, the President remarked that he did not like Marshall's use of the

word "critical" since he wanted help in carrying out his idea rather than

obstacles placed in the way.1

The Army planners that same day presented a report on the logistical implications of reinforcing PRICELESS.2 It indicated that, on the basis of

optimistic predictions of available personnel lift in the Atlantic, it

would be possible, by 1 May 1944, to build up in the United Kingdom the

force of 1,300,000 U.S. troops provided for in TRIDENT estimates and, in

addition, to lift approximately 100,000 more either to the United Kingdom

or to some other theater.3 Recent troop lists prepared by the European

Theater of Operations, however, called for over 1,400,000 U.S. troops by I

May 1944 to make up balanced striking forces for the Combined Bomber

Offensive (POINTBLANK) and OVERLORD. If the TRIDENT estimates of 1,300,000

were adhered to, and if the optimistic shipping estimates for the

Atlantic proved correct, the Army planners admitted that seven U.S.

divisions could be lifted to North Africa by the middle of 1944 without

affecting the availability of divisions for OVERLORD as set at TRIDENT.

But, the planners pointed out, the utilization of personnel shipping to

lift troops to the Mediterranean before June 1944 would not contribute as

much to striking a direct decisive blow at the European Axis as the

employment of the same shipping to insure a well-balanced force in the

United Kingdom. They observed, moreover, that it was the opinion of

General Eisenhower and of the JCS that the force

[212]

currently committed to the Mediterranean (less the seven divisions

scheduled for transfer to the United Kingdom) would be adequate to achieve

the desired objective of occupying Italy to a line north of Rome, seizing

Sardinia and Corsica, and making a diversionary effort against France from

the Mediterranean. The addition of seven divisions to General Eisenhower's

forces in the Mediterranean would make a total of thirty-one divisions

available in that area, as compared with twenty-nine for the main effort,

OVERLORD. The Army planners therefore called for the full troop lift of

1,400,000 to be allocated to OVERLORD and POINTBLANK.4

At the session of the JCS at noon on 10 August, shortly before a

scheduled conference of the JCS with the President, General Marshall

reported the President's inclination to furnish seven new divisions from

the United States to replace the seven veteran divisions scheduled for

transfer to the United Kingdom. Arguing that this reinforcement of

PRICELESS would occur at the expense of the build-up for OVERLORD, he

emphasized that, even if the seven additional divisions were provided,

they could not arrive in the Mediterranean before June 1944. The

President, he went on, should be informed of General Eisenhower's report

that he had sufficient resources to conduct the proposed operations in

Italy. The President should also be apprised that an additional force of

seven divisions would in reality constitute an expeditionary force

available for use in the Balkans. General Marshall felt that the President

was opposed to operations in the Balkans, and particularly to U.S. troop

participation in them, on the ground that they represented an uneconomical

use of shipping and also because of the political implications involved.

In rallying the JCS against the Presidential proposal, General Marshall

was supported by Admiral King, who was particularly fearful lest the

provision of shipping for seven new divisions to the Mediterranean

seriously curtail planned Pacific operations.5

Meanwhile-at one o'clock that same afternoon-Secretary of War Stimson, who

had recently returned from the United Kingdom, conferred with the

President at the White House. That very morning, he had decided to present

his conclusions to the President in writing. So serious did he consider

the action he was about to recommend decisions that would affect

Marshall's position in the Washington high command-that he called Marshall

in to let him read what he was going to say, in case Marshall had any

vital objections. Stimson recorded the reaction of the Army Chief of Staff

in his diary entry for that day: "He said he had none but he did not want

to have it appear that I had consulted him about it. I told him that for

that very reason I had signed the paper before I showed it to him or

anyone else." Stimson also recorded that the conference that followed at

the White House was "one of the most satisfactory" he had ever had with

the President.

In the course of the conversation he produced his letter of conclusions.

In it Stimson reasoned:

[213]

We cannot now rationally hope to be able to cross the Channel and come to

grips with our German enemy under a British commander. His Prime Minister

and his Chief of Imperial Staff are frankly at variance with such a

proposal. The shadows of Passchendaele and Dunkerque still hang too

heavily over the imagination of these leaders of his government. Though

they have rendered lip service to the operation, their hearts are not in

it and it will require more independence, more faith, and more vigor than

it is reasonable to expect we can find in any British commander to

overcome the natural difficulties of such an operation carried on in such

an atmosphere of his government.

Stimson went on to point out that the difference between the Americans and

the British was "a vital difference of faith." The U.S. staff believed

that only by massing the great vigor and might of the two countries under

overwhelming mastery of the air could Germany be defeated. The British

theory was that Germany would be beaten by a "series of attritions" in the

Mediterranean and the Balkans. The USSR, to which both the United States

and Great Britain were pledged to open a second front, would not be fooled

by "pinprick warfare"-a special danger in the light of postwar problems.

Stimson concluded his letter:

I believe therefore that the time has come for you to decide that your

government must assume the responsibility of leadership in this great

final movement of the European war which is now confront- 'in us. We

cannot afford to confer again g and close with a lip tribute to BOLERO

which we have tried twice and failed to carry out . . . . Nearly two years

ago the British offered us this command. I think that now it should be

accepted-if necessary, insisted on.

Finally the time had come to put ". . . our most commanding soldier in

charge of this critical operation at this critical time." Lincoln had had

to fumble by trial and error until he discovered the right man. Wilson had

to choose a relatively unknown. But Roosevelt was far more fortunate. He

had General Marshall, who

. . . already has a towering eminence of reputation as a tried soldier and

as a broadminded and skillful administrator. This was shown by the

suggestion of him on the part of the British for this very post a year and

a half ago. I believe that he is the man who most surely can now by his

character and skill furnish the military leadership which is necessary to

bring our two nations together in confident joint action in this great

operation. No one knows better than I the loss in the problems of

organization and world-wide strategy centered in Washington which such a

solution would cause, but I see no other alternative to which we can turn

in the great effort which confronts us.

The President, Stimson noted, "read it [the letter] through with very

apparent interest,, approving each step after step and saying finally that

I had announced the conclusions which he had just come to himself."

6

Later on 10 August the JCS joined the Secretary and the President at the

White House to discuss the coming conference with the British at Quebec.7

At this meeting the President reported that, from his conversations with

the Secretary of War, he had learned that the

[214]

Prime Minister currently favored operations against the Balkans but was

opposed to an operation against Sardinia. The Secretary of War qualified

this statement, pointing out that Mr. Churchill had disclaimed any wish

to land troops in the Balkans, but had indicated that the Allies could

make notable gains in that area if the Balkan peoples were given more

supplies. The Secretary of War affirmed that the British Foreign

Secretary, Mr. Anthony Eden, wished the Allies to invade the Balkans. To

this the President added that the British Foreign Office did not wish the

Balkans to come under Soviet influence, and therefore the British wished

"to get to the Balkans first." He himself did not follow the logic of the

British thinking on the Balkans. He did not believe, he stated, that the

USSR desired to take over the Balkan states but rather that the USSR

wished to "establish kinship with other Slavic people." He assured the

U.S. military leaders that he himself was opposed to Balkan operations. In

arguing against a Balkan operation the President reasoned along the lines

of the view that had been emphasized by General Marshall and General

Handy on the undesirability of basing hopes for victory on political

imponderables. He declared that it was "unwise to plan military strategy

based on a gamble as to political results."

8

In recommending against the President's proposal for replacing the seven

trained divisions to be taken from the Mediterranean with seven from the

United States, General Marshall and Admiral King repeated the arguments

they had advanced at the meeting of the JCS earlier in the day. On the

basis of the War Department study he had made, General Marshall reported

that the seven new divisions could be transported to North Africa by the

end of June 1944 and the planned build-up for OVERLORD could still be

executed. But he emphasized General Eisenhower's belief that even without

the seven divisions to be sent to the United Kingdom he would still have a

sufficient force to conduct the projected operations in Italy, capture

Sardinia and Corsica, and have fourteen divisions available for an

invasion of southern France in co-ordination with OVERLORD. Dispatching an

extra seven divisions to the Mediterranean, Marshall argued, would meet

the desires of Mr. Churchill and Mr. Eden, invite their use in an invasion

of the Balkans, and so extend the Mediterranean operations as to have a

harmful effect on the main effort from the United Kingdom. Following the

presentation of these arguments, the President announced that he would

advocate leaving General Eisenhower with his current build-up, less the

seven divisions earmarked for transfer to the United Kingdom.

Turning to the basic question in grand strategy, Admiral King suggested to

the President that, if the British insisted upon abandoning OVERLORD or

postponing OVERLORD indefinitely, the United States should abandon the

project. The President replied with the optimistic view that the United

States itself could, if necessary, carry out the cross-Channel operation.

He felt certain that the British would make the necessary bases available

to the United States for the operation. General Marshall ob-

[215]

jected to the President's suggestion on the ground that fifteen British

divisions were already available in the United Kingdom. In no other place

in the world, he maintained, could fifteen divisions be put into an

operation without entailing great transportation and supply problems. The

President affirmed his wish for the preponderance of U.S. forces in

OVERLORD from the first day of the assault in order to be able to justify

the choice of an American commander for the operation. In line with the

emphasis that had been placed by Washington military planners on the

wastage in the Allied war effort resulting from past divergences from the

main plot, General Marshall cautioned the President against subsequent

changes in basic decisions. He was prepared to accept only minor

diversions from the main plan-and those only when absolutely necessary.

It was especially important to avoid such dislocation of the American war

effort as had resulted earlier from the change from BOLERO to TORCH.

Marshall reminded the President that every such shift in plans resulted

in changes in production, loading of convoys, and other phases of U.S. war

mobilization, which "reached as far back as the Middle West in the United

States."

9

The U.S. leaders left the meeting of 10 August agreed to insist on the

continuation of the current build-up for the cross-Channel operation from

the United Kingdom and on carrying Out OVERLORD as the main U.S.-U.K.

effort. The JCS now had the President behind them in their plans for

Europe.10 When they

had touched on strategy and planning differences in the war against Japan,

the JCS had urged the President to try to persuade the Prime Minister to

put full British support behind the projected Burma operations-operations

to which the President had already agreed on 26 July.11

Stimson has recorded the delight of the U.S. staff with the "clear and

definite" stand of the President on the conduct of the war against

Germany, marking the full acceptance by the Commander in Chief of the

military policy for which Stimson and Marshall had been fighting.12 The

ranks of the American high command appeared closed as never before.

Cheered as the staff was, the question remained whether the President and

his military advisers could see the agreed policy through in the

conference with the British.

[216]

The Conferees Assemble

After the completion of their preparations, the U.S. military delegation

left for Quebec. In preparing for the meetings with the British, American

military planners as well as their chiefs had carefully studied British

preparations, representation, and techniques in negotiations at past

conferences and had taken steps to match them.13

At Quebec, amid the quaint 18th century charm of the French city, the

military staffs were quartered and held their meetings in the impressive

Château Frontenac overlooking the St. Lawrence River. The President and

Prime Minister made their headquarters at the old fortress known as The

Citadel, close by the historic Plains of Abraham, and currently the summer

seat of the Governor General of Canada. Special ramps had been installed

for the President's use, and the two plenary sessions of the conference

were held here for his convenience. As the delegations assembled, the news

from the war fronts-especially of the war against Germany-was definitely

encouraging. Reports of Italian peace moves were persistent. In Sicily the

campaign was in its final stages, and by 17 August-early in the

conference-Sicily was entirely in Allied hands. On the Eastern Front the

Russians had seized the initiative and had begun to drive the Germans back

to their homeland. The Combined Bomber Offensive had finally gotten under

way in earnest. In the war on the U-boats in the Atlantic, the tide that

had turned in the spring of 1943 was running even more strongly in Allied

favor. American intelligence estimates on the eve of the conference

predicted that the German war against Allied shipping would continue, but

with diminishing effect; that the Germans would try, during 1943, to

improve their defensive position in the USSR, and to impair Soviet

offensive capabilities by attrition; and that the Germans would stand on

the strategic defensive on all fronts during 1944, yielding outlying

territories only under compulsion. The estimates held that Germany would

resist as long as there was any hope of a negotiated peace.14

In Alaska, U.S. troops had occupied Kiska, and the Japanese had finally

withdrawn from the Aleutians. General MacArthur's Southwest Pacific

forces were ready to advance on Salamaua in New Guinea and South Pacific

forces were driving ahead on the island of New Georgia. Only in the CBI

had the front remained more or less stationary. U.S. intelligence

estimates on the Pacific and Far East situation held that Japan would

probably remain on the strategic defensive unless convinced that an

attack by the USSR was imminent or that

[217]

CHATEAU FRONTENAC, OVERLOOKING THE ST. LAWRENCE RIVER, scene of QUADRANT

Conference, August 1943.

[218]

CHATEAU FRONTENAC, OVERLOOKING THE ST. LAWRENCE RIVER, scene of QUADRANT

Conference, August 1943.

[218]

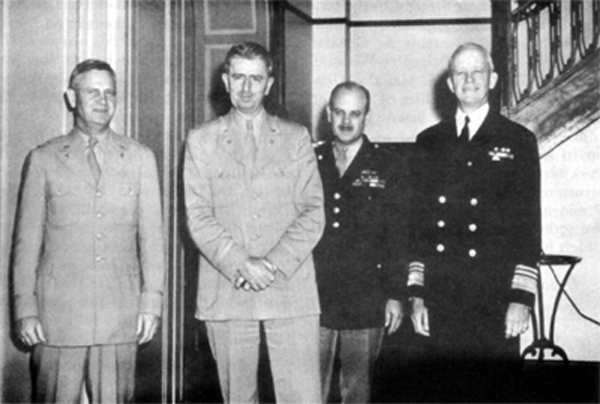

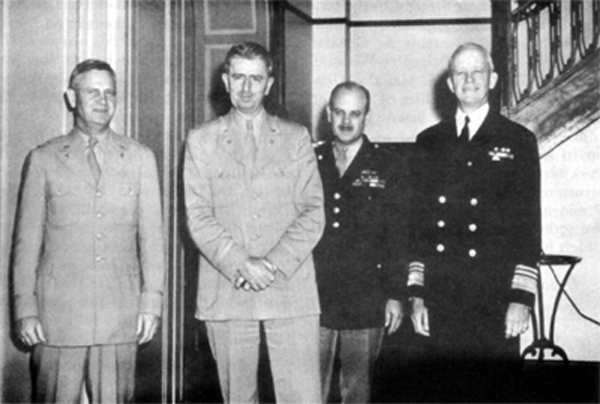

TOP MILITARY PLANNERS AT QUEBEC. From left: Maj. Gen Thomas T. Handy,

Brig. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, Mai. Gen. Muir S. Fairchild, and Vice Adm.

Russell Willson.

major operations were to be launched by the Allies in China. Serious

reverses for the Allies in the Pacific or for the Soviet Union in Europe

might also lead to a shift by Japan to the offensive.15

American and British planners arrived on the scene to lay the groundwork

for the conference a few days before the principals began-their

sessions.16 Then in the eleven-day period of the conference between 14 and

24 August 1943, the U.S. and British Chiefs of Staff met

for a full-dress debate on Allied strategy in the war. Present among the

American delegation to assist General Marshall were General Handy, the

Assistant Chief of Staff, OPD, and General Wedemeyer, the Army planner,

and a considerable number of other Washington Army planners delegated for

duties on the planning and working staff level.17

[219]

TOP MILITARY PLANNERS AT QUEBEC. From left: Maj. Gen Thomas T. Handy,

Brig. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, Mai. Gen. Muir S. Fairchild, and Vice Adm.

Russell Willson.

major operations were to be launched by the Allies in China. Serious

reverses for the Allies in the Pacific or for the Soviet Union in Europe

might also lead to a shift by Japan to the offensive.15

American and British planners arrived on the scene to lay the groundwork

for the conference a few days before the principals began-their

sessions.16 Then in the eleven-day period of the conference between 14 and

24 August 1943, the U.S. and British Chiefs of Staff met

for a full-dress debate on Allied strategy in the war. Present among the

American delegation to assist General Marshall were General Handy, the

Assistant Chief of Staff, OPD, and General Wedemeyer, the Army planner,

and a considerable number of other Washington Army planners delegated for

duties on the planning and working staff level.17

[219]

The Prime Minister brought to the conference a full staff complement,

including such special assistants as General Morgan (COSSAC), Brigadier

Wingate, and Maj. Gen. A. W. S. Mallaby, General Wavell's Deputy Chief of

Staff for Operations, who had flown in from India.18 Churchill arrived at

Quebec on to August, then journeyed to Hyde Park for a brief visit with

the President, returning to Quebec on 15 August. The President did not

arrive at Quebec until the 17th-three days after the Combined Chiefs had

begun their sessions.

Debating the Issues in the War

Against Germany

The Arguments

In the discussions at QUADRANT between the staffs on the war against

Germany, the U.S. Joint Chiefs sought a final resolution of the question

whether the main effort was to be made from the United Kingdom or in the

Mediterranean.19 In the process, they sought agreement on the relationship

between operations in the two areas. As usual in the conferences with the

British in mid-war, General Marshall served as the principal American

spokesman on European strategy. In part this was recognition of his strong

convictions and his talents in advocacy and military diplomacy. In part it

was acceptance of the view that the American concept of European strategy

was essentially that of the U.S. Army and its defense in debate with the

British should properly be conducted by the War Department spokesman. As

already suggested, Marshall was convinced that a final choice between the

basic alternatives of cross-Channel versus Mediterranean now had to be

made. He was prepared and willing to risk a showdown with the British at

this point-the consequences of which he fully realized. He made clear to

his colleagues that

. . . we must go into this argument in the spirit of winning. If, after

fighting it out on that basis, the President and Prime Minister decided

that the Mediterranean strategy should be adopted, he wished that the

decision be made firm in order that definite plans could be made with

reasonable expectation of their being carried out.20

As it had previously decided, the American delegation immediately

presented its proposal that OVERLORD be given overriding priority over

other operations in the European theater.21

Sir Alan Brooke replied for the British Chiefs of Staff that the British

were in complete agreement with the U.S. Chiefs of Staff that OVERLORD

should be the major U.S.-U.K. offensive for 1944. Nevertheless, he went on

to stress forcefully the necessity of achieving the three main conditions

on which the success of the OVERLORD plan was based: (1) the

[220]

reduction in German fighter strength; (2) the restriction of German

strength in France and the Low Countries and of German ability to bring in

reinforcements during the first two months; and (3) the solution of the

problem of beach maintenance. To create a situation favorable to a

successful OVERLORD was the main British aim of Allied operations in

Italy. The desired Allied, vis-à-vis enemy, strength, Brooke emphasized,

could be attained by operations in Italy to contain the maximum German

forces and by air action from the most suitable Italian bases to reduce

German fighter forces. In this connection Sir Charles Portal argued the

advantages of gaining the northern Italian airfields.22 Not too

surprisingly, the British soon turned the discussion to the much-debated

question of the seven divisions. If the seven divisions were withdrawn

from the Mediterranean, the British Chiefs argued, the Americans and

British would run risks in the Mediterranean that might preclude or

jeopardize success in OVERLORD. On the basis of this reasoning, Sir Alan

Brooke concluded, therefore, that the decision sought by the U.S. Joint

Chiefs between OVERLORD and operations in the Mediterranean would be "too

binding."

23

In reply, General Marshall questioned whether the necessary conditions for

OVERLORD could be brought about only by increasing Allied strength in the

Mediterranean. If Italian resistance proved to be weak, he agreed, the

Allies ought to seize as much of Italy as possible. While it would be

better if the Allies held the northern airfields of

Italy, he believed that almost as much could be accomplished from the

Florence area. In his opinion, a successful OVERLORD could be insured

only by giving it an overriding priority. Unless OVERLORD were given that

priority, the operation might never be launched. Unless the seven

divisions from the Mediterranean were dispatched and the necessary means

were concentrated for OVERLORD, OVERLORD would at best become a

"subsidiary operation." A delay in such decisions not only would hinder

the OVERLORD build-up but also would have repercussions on Pacific

operations. Marshall again emphasized, this time to the combined staffs,

that any exchange of troops contrary to TRIDENT agreements "would absorb

shipping" and upset supply arrangements "as far back as the Mississippi

River." Unless OVERLORD were given an overriding priority, General

Marshall went on, the entire U.S.-U.K. strategic concept would have to be

revised. In that event, the United States and the United Kingdom would

have to rely on air bombardment alone to defeat Germany, and only a

reinforced U.S. Army corps for an "opportunistic" cross-Channel

operation might well be left in the United Kingdom. Although the Combined

Bomber Offensive had accomplished great results, the final outcome of that

operation-and the very possibility of an opportunistic cross-Channel

undertaking - remained "speculative." Such a recasting of strategy, he

pointed out to the British, might lead to a possible reorientation of

American offensive efforts toward the Pacific.24

The British position, as could be expected, was not inflexible. On 16 Au-

[221]

MEMBERS OF U.S. AND BRITISH STAFFS CONFERRING, Quebec, 23 August 1943.

Seated around the table from left foreground: vice Adm. Lord Louis

Mountbatten, Sir Dudley Pound, Sir Alan Brooke, Sir Charles Portal, Sir

John Dill, Lt. Gen. Sir Hastings L. Ismay, Brigadier Harold Redman, Comdr.

R. D. Coleridge, Brig. Gen. John R. Deane, General Arnold, General

Marshall, Admiral William D. Leahy, Admiral King, and Capt. F. B. Royal.

gust, General Marshall informed his American colleagues that Churchill had

told him the previous evening "that he had changed his mind over OVERLORD

and that we should use every opportunity to further that operation."

Marshall had taken the opportunity to tell the Prime Minister that he

could not agree to the logic of supporting the main effort by withdrawing

strength from it to reinforce the effort in Italy. In Marshall's view,

the British approach to OVERLORD was by "indirection."

25

To counter the British reservations and qualifications, the JCS on 16

August accepted for presentation to the CCS proposals submitted by General

Handy. Handy called for the acceptance by the CCS of the TRIDENT decision

for OVERLORD-including the definite allotment of forces for it-and of the

American proposal of overriding priority for OVERLORD, without

reservations or conditions. The JCS decided to withhold

[222]

MEMBERS OF U.S. AND BRITISH STAFFS CONFERRING, Quebec, 23 August 1943.

Seated around the table from left foreground: vice Adm. Lord Louis

Mountbatten, Sir Dudley Pound, Sir Alan Brooke, Sir Charles Portal, Sir

John Dill, Lt. Gen. Sir Hastings L. Ismay, Brigadier Harold Redman, Comdr.

R. D. Coleridge, Brig. Gen. John R. Deane, General Arnold, General

Marshall, Admiral William D. Leahy, Admiral King, and Capt. F. B. Royal.

gust, General Marshall informed his American colleagues that Churchill had

told him the previous evening "that he had changed his mind over OVERLORD

and that we should use every opportunity to further that operation."

Marshall had taken the opportunity to tell the Prime Minister that he

could not agree to the logic of supporting the main effort by withdrawing

strength from it to reinforce the effort in Italy. In Marshall's view,

the British approach to OVERLORD was by "indirection."

25

To counter the British reservations and qualifications, the JCS on 16

August accepted for presentation to the CCS proposals submitted by General

Handy. Handy called for the acceptance by the CCS of the TRIDENT decision

for OVERLORD-including the definite allotment of forces for it-and of the

American proposal of overriding priority for OVERLORD, without

reservations or conditions. The JCS decided to withhold

[222]

the second part of General Handy's proposals-alternative recommendations

for a radical reversal in U.S. strategic policy -calling for the

abandonment Of OVERLORD and placing the main effort in the Mediterranean,

in the event the British Chiefs of Staff refused to back OVERLORD

wholeheartedly. On this "Mediterranean alternative" scheme, foreshadowed

in General Hull's analysis a month earlier, the JCS were noncommittal.26

At the same time, the JCS decided immediately to inform the President, who

had not yet arrived at the conference, of the emerging divergences in

British and American staff views and especially of their concern over

apparent reservations of the British on OVERLORD. General Handy was

delegated to fly to Washington at once.27

On 17 August the President arrived in Quebec to lend his support to

OVERLORD. By that time-after three days of staff debate-it was already

clear that a compromise was in the making and that the U.S. staff would

have to accept something less than "overriding priority" for the

operation.28

In arguing his case before the President and CCS in plenary session,

Churchill declared that he had not favored SLEDGEHAMMER in 1942 Or ROUNDUP

in 1943, but he "strongly favored" OVERLORD for 1944.

29

His objections to the earlier operations, he stated, had been removed. He

wished all to understand, nevertheless, that the implementation of the

OVERLORD plan depended on the fulfillment of certain conditions. One of

these conditions was that no more than twelve mobile German divisions were

to be in northern France at the time the operation was mounted. Another

was that the United States and the United Kingdom had attained definite

superiority over the German fighter forces at the time of the assault. He

urged that the OVERLORD plan be subject to revision by the CCS in the

event that the German strength exceeded the twelve mobile divisions. He

also suggested that the Allies keep a "second string to their bow" in the

guise of a prepared plan to undertake Operation JUPITER-the invasion of

Norway, long a favorite project of his.30

Churchill and General Marshall agreed that an increase in the initial

assault force would greatly strengthen the OVERLORD undertaking. The Prime

[223]

Minister called for an addition of at least 25 percent strength. General

Marshall pointed out that actually there would be four and one half

divisions in the assault rather than the force of three divisions

suggested at the TRIDENT Conference. The President seized the

opportunity to express his desire, already stated to the JCS, to speed

the shipment of U.S. troops to the United Kingdom. General Marshall

repeated that the matter was being studied. At the same time, he

emphasized to the conferees that the greatest limiting factor on all the

prospective Anglo-American operations was the shortage of landing craft.

Had landing craft been available, Marshall pointed out, the

Anglo-American forces could have already made an entry into Italy.

31

Turning to Mediterranean operations, the British and U.S. military leaders

sought to speed the elimination of Italy from the war and decide the

course of action to be taken after the prospective landings in Italy.

Keeping abreast of current plans of General Eisenhower's staff for two

amphibious assaults to be launched early in September- BAYTOWN (across the

Strait of Messina) and AVALANCHE (into Salerno Bay)-they took steps to

expedite negotiations on Italian peace feelers.32 On the delicate question

of how far to go in Italy, the Prime Minister assured the conferees that

he was not committed to an advance beyond the Ancona-Pisa line.33

All were agreed on the desirability of capitalizing on the Italian fields

as far north as they became available and thereby extending the range of

the Combined Bomber Offensive.34

The Prime Minister indicated his hesitancy in placing Anglo-American

divisions in southern France as a diversion for OVERLORD and said that he

doubted that the French divisions would be capable of undertaking such an

operation. Sir Alan Brooke pointed out that there were two routes by which

such a diversion might be achieved: a drive west from Italy, if the Allied

forces had been able to advance far enough north, and an amphibious

operation against southern France. Such a diversion in southern France,

he also maintained, would depend on what the German reactions had been.

Troops would be landed in southern France only if the Germans had been

compelled to withdraw a number of their divisions from that area. In the

light of these conditions, the Prime Minister suggested an alternative

plan he termed "air-nourished guerrilla warfare" in southern France. This

proposal envisaged flying in supplies for French guerrillas at a

rendezvous point in the mountains thirty miles inland from the southern

French coast. The President went even further and voiced the belief that

guerrilla operations could be conducted in south-central France as well

as in the Maritime Alps.35

[224]

As for operations in the Balkans, the President indicated his desire to

have the Balkan divisions that the Allies had trained, particularly the

Greeks and Yugoslavs, operate in their own countries. He expressed the

belief that it would be advantageous if these Balkan divisions would

follow-up and harass the Germans, should the latter decide to withdraw

from the Balkans to the line of the Danube. The Prime Minister suggested

that commando forces could also operate in support of the guerrillas on

the Dalmatian coast. Neither the British nor the American leaders

expressed an interest in offensive land operations by the United States

and Great Britain in the Balkans.36

A persistent note pervaded the discussion of the American delegates-the

fear of draining strength and means away from the cross-Channel operation

and the consequent desire to restrict Mediterranean operations. How to

keep the war in the Mediterranean a limited one contributing to OVERLORD

and early victory over Germany was the problem. In any event, whatever

measures were undertaken to eliminate Italy, establish bases on the

mainland, seize Sardinia and Corsica, and launch an operation in southern

France in conjunction with OVERLORD, should be carried out with the forces

allotted at TRIDENT. To such limits the British raised objections. They

argued strongly the need for more leeway in allocating resources in order

to insure the success of the Mediterranean operations-all the more

important now to pave the way for OVERLORD. Hence, they saw great danger

in accepting rigid commitments for the Mediterranean-a straight jacket likely to

jeopardize the Allied cause in the whole European-Mediterranean area.

Staff differences on the question of Mediterranean commitments were

themselves symptomatic of more basic and lingering divergences in

European strategy-on the role of preparatory operations and the timing of

the main blow. Back of these divergences lay the even more fundamental

differences in approach to strategy-the claims of waging attritional

warfare versus those of concentration in a selected area. Though a

definitive reconciliation of strategic methods and theories might be

beyond the scope of the staffs assembled in conference, the practical

issue on which the larger divergences came to settle-the question of

Mediterranean commitments for the following year posed a problem for

immediate compromise.

Plan RANKIN

In the course of discussing operations in the European-Mediterranean area,

British and American military leaders also considered the possibility of

an emergency return to the Continent. For this a new plan was at hand-Plan

RANKIN. Prepared by General Morgan's COSSAC staff, it provided for an

emergency return to the Continent in the winter of 1943-44, or early

spring of 1944 before the target date for OVERLORD.37 Just as OVERLORD

represented

[225]

the culmination of the thinking on decisive cross-Channel operations that

had been embodied in ROUNDUP and ROUNDHAMMER, so RANKIN signified a new

version of the SLEDGEHAMMER concept of an opportunistic operation. Added

weight was given to the urgency of this planning in view of the

President's expressed interest in it at QUADRANT and particularly in the

light of his expressed desire at the conference that the "United Nations

troops . . . be ready to get to Berlin as soon as did the Russians."

38

Plan RANKIN set forth three contingencies for the emergency return: Case

A: a substantial weakening of German resistance; Case B: a withdrawal of

the German forces from occupied countries; or Case C: unconditional German

surrender.39 The COSSAC planners considered that any of these three

contingencies might evolve from the continuation of such encouraging

developments as the German reverses on the Eastern Front, the growing

threat to Germany in Italy and the Balkans, the setback to the German

submarine campaign, and the increasing Allied air offensive. The COSSAC

planners shaped their proposals for the emergency operations on the

considerable alteration of the Allied strategic situation in the European-Mediterranean

area since the incorporation of the SLEDGEHAMMER concept into the War

Department BOLERO-ROUNDUP plan in the spring of 1942.

In Case A of Plan RANKIN the COSSAC planners set as the objective a lodgment on the Continent from which

the U.S. and British forces could complete the defeat of Germany. The

assault area was to be the same as that for OVERLORD-the Cotentin-Caen

sector of northwestern France. If there was a sufficient disintegration

in morale and strength of the German armed forces, an operation against

organized opposition could be undertaken in January or February 1944 to

capture the Cotentin Peninsula. Alternatively, a modified OVERLORD would

be put into effect in March or April 1944. In either case, the COSSAC

planners believed, the port of Cherbourg would have to be captured within

the first forty-eight hours to provide adequate maintenance. In Case A of

Plan RANKIN, as in OVERLORD, diversionary operations in the Pas-de-Calais

area, and from the Mediterranean would probably be necessary.

In Case B of Plan RANKIN the COSSAC planners also called for a lodgment

on the Continent from which the Allies could complete the defeat of

Germany. The first place of entry for the main Allied forces in this event

was to be Cherbourg.

In Case B, moreover, substantial Allied forces were

to be sent from the Mediterranean to occupy the ports of Marseille and

Toulon and move northward as required.

In Case C Of RANKIN the COSSAC planners stated that the object was to

occupy as quickly as possible areas from which the Allies could enforce

the terms of unconditional surrender imposed by their governments on

Germany. Under the general direction of the Supreme Allied Commander,

France, Belgium, and the Rhine Valley from the Swiss frontier to Duesseldorf were to be under

[226]

the control of the U.S. forces, with British representation in the

liberated countries; Holland, Denmark, Norway, and northwest Germany from

the Ruhr Valley to Luebeck were to compose an area under the control of

the British forces, with American representation in the liberated

countries.

The COSSAC planners concluded that the forces allotted for OVERLORD should

also be considered available for RANKIN. In all three of the contingencies

they emphasized the importance of rehabilitating the liberated countries.

They therefore recommended that the United States and the United Kingdom

lay down policies to govern the establishment of military governments in

enemy territory to be occupied by Allied troops and of national

administrations in the liberated Allied territories. Nuclei of combined

Anglo-American civil affairs staffs in London for Germany and for each

Allied and friendly country within the sphere of the Supreme Allied

Commander should be established.40

In discussing RANKIN, Sir Alan Brooke stated the hope of the British

Chiefs that fewer forces might be used for occupation purposes than set

forth in the plan. Admiral Leahy replied that the JCS shared this view.

The U.S. Joint Chiefs recommended that RANKIN be approved in principle and

that it be continuously reviewed.

41

The CCS approved these suggestions, noting that, in line with the plan,

the U.S. Joint Chiefs would appoint a commanding general, staff, and

headquarters for the U.S. Army group in the United Kingdom.42

Compromises and Agreements

The operations in 1943-44 for the defeat of the Axis Powers in Europe,

approved by the CCS, the President, and the Prime Minister at QUADRANT,

represented another compromise of British and American views on strategy.

The conferees agreed that Operation OVERLORD was to be the main

Anglo-American effort in Europe with a target date of 1 May 1944, approved

the outline plan of General Morgan for Operation OVERLORD, and authorized

him to proceed with preparations. Because of differences in British and

American views of the relationship between OVERLORD and Mediterranean

operations, the U.S. delegation had to yield on its desire for overriding

priority for OVERLORD and accept a compromise statement that, in the event

of a shortage of resources, avail-' able means were to be disposed and

utilized with the "main object" of insuring the success Of OVERLORD.43

The American delegation also accepted, as 3n added qualification to its

original proposal that operations in the Mediterranean area be conducted

with the forces allotted at TRIDENT, the clause upheld by the British

representatives-"except insofar as these may be varied by decision of the

Combined Chiefs of Staff."

44

[227]

The same proviso was attached by the British to the planned return of the

seven divisions from the Mediterranean to the United Kingdom for OVERLORD,

though Marshall had fought hard for a decision without strings. The

conferees also accepted the British proposal that in the event OVERLORD

could not be executed, JUPITER should be considered as an alternative and

called for plans to be developed and kept up to date for such an

operation. All agreed that the Combined Bomber Offensive (POINTBLANK) was

to remain in the "highest strategic priority" and was to. be extended from

all suitable bases-particularly from Italy and the Mediterranean -as a

prerequisite for OVERLORD.

As for Mediterranean operations, the conferees agreed on the basic

outlines of the three phases of operations in Italy that the JCS had

suggested in their proposals to the CCS before QUADRANT. The first phase,

as accepted at QUADRANT, called for the elimination of Italy from the war

and the establishment of air bases in the Rome area and, if possible,

farther north.45 For the moment at least, these general objectives in

Italy represented a meeting ground between the aims of the Americans and

the desires of the British.

The second phase involved, as the JCS had recommended, the seizure of

Sardinia and Corsica. In this connection the delegates decided to request

General Eisenhower to examine the possibilities of intensifying subversive

activities on the islands in order to facilitate entry

into them. This action stemmed largely from the American staff's urging,

especially for Sardinia. The JCS had themselves been persuaded to make

this proposal to the CCS by Generals Marshall, Handy, and Wedemeyer in

the course of staff discussions during the conference. In the meeting of

the JCS on 19 August 1943, Generals Marshall, Handy, and Wedemeyer had

argued that, in view of the shortage of landing craft available to General

Eisenhower, and in the light of the opportunity to test the effectiveness

of the Office of Strategic Services organization, "fifth column activity"

should be undertaken by the OSS on Sardinia.46

In the third phase of operations in Italy, the conferees accepted the JCS

provision for maintaining constant pressure on German forces in northern

Italy and creating conditions favorable for the eventual entry of Allied

forces, including most of the re-equipped French Army and Air Force, into

southern France. Also in keeping with the American proposal, offensive

operations against southern France were to establish a lodgment in the

Toulon-Marseille area and exploit northward in order to create a diversion

in connection with

[228]

OVERLORD. Omitted, however, was the qualifying phrase, "with available

Mediterranean forces" that the JCS had sought.47 In line with the

proposals of the President and Prime Minister, it was agreed that "air

nourished guerrilla operations" in the southern Alps would be conducted if

feasible.48 Also approved was the rearmament of French units up to and

including eleven divisions by 31 December 1943. As a result of the

deliberations at the conference, the CCS sent a directive to General

Eisenhower calling for his appreciation and outline plan on operations in

southern France, to be submitted to the CCS by 1 November 1943.49 In the

preparation of the plan, Eisenhower was to consult with the Supreme

Commander of the cross-Channel operations (whoever might be appointed) or

his chief of staff so that his planning could be correlated with the

requirements of OVERLORD.

With little debate, the delegations at QUADRANT rejected the idea of

offensive ground operations by the United States and the United Kingdom in

the Balkan area. Operations in that area were to be limited to supplying

Balkan guerrillas by air and sea, minor commando raids, and bombing of

strategic objectives. In keeping with the by then long familiar concern of

the JCS for safeguarding the lines of communications in the Mediterranean,

appropriate Allied forces were to be deployed in northwest Africa so long

as the possibility of a German invasion of the Iberian Peninsula remained.

From the military point of view, the time was not considered right for

Turkey to enter the war, but the United States and Great Britain were to

continue to supply such equipment to Turkey as they could spare and the

Turks could absorb.50

Further measures were to be undertaken in the Atlantic to strengthen

operations against the U-boats. Especially attractive was the

possibility of using the Azores as a base for intensified sea and air

operations and for the development of an air-ferry route.51

During the discussions, the British had indicated that negotiations over

the Azores with the Portuguese Government, undertaken by the British

Foreign Office in consultation with the British Chiefs of Staff, were

approaching a conclusion. The Portuguese had agreed to the entry of a

small British force into the Azores on 8 October (Operation ALACRITY. The

U.S. delegation was assured by the British Chiefs of Staff that, upon

gaining entry into the Azores, the British would seek to make arrangements

for U.S. aircraft to use the airfields in the Azores as a base of

operations and in transit.52

Finally, on the President-Prime Minister level, a significant agreement

was reached at Quebec on the question of

[229]

command for the projected coalition effort in the European-Mediterranean

area. Earlier, the two leaders had agreed that, since the United States

had the African command, it was but fair that the commander of the

cross-Channel operation be British. With Presidential agreement, Churchill

had gone so far as to nominate General Brooke, Chief of the Imperial

Staff, for the post and early in 1943 had so informed him. The logic of

events, however, now compelled a change. Churchill has since recorded:

. . . as the year advanced and the immense plan of the invasion began to

take shape, I became increasingly impressed with the very great

preponderance of American troops that would be employed after the original

landing with equal numbers had been successful, and now at Quebec, I

myself took the initiative of proposing to the President that an American

commander should be appointed for the expedition to France. He was

gratified at this suggestion, and I dare say his mind had been moving that

way.53

As already observed, the President's mind indeed had been moving in that

direction. An American officer, they therefore agreed, would command

OVERLORD, and a British commander would take over in the Mediterranean,

the time for the change to depend upon progress in the war. The way was

thus cleared, as Stimson had strongly urged before the conference, for an

American leader to take over the command of the cross Channel operation.

Whether that prize would fall to Marshall-as Stimson had hoped-or whether

Marshall, like his British counterpart, would be passed over by the force

of circumstances, remained to be seen.

Discussion on the War Against Japan

The British had originally intended to bypass the war against Japan at

QUADRANT, but consideration of it consumed as much time and effort as it

had at Casablanca and TRIDENT. Fear that the Pacific conflict might

degenerate into a long war of attrition or stalemate made the United

States anxious to spell out the future course and timing of operations.

British reluctance to commit Allied resources too heavily in the Pacific

until after the Germans collapsed was understandable, but could not

withstand the growing American pressure for accelerated action. Two basic

questions demanded consideration: selection of the main line of approach

to the Japanese homeland and Great Britain's role in the Pacific after

Germany was defeated. Exploration of these vital problems at QUADRANT

brought to light areas of Anglo-American disagreement that would require

still further examination.

As usual in the midwar international conferences, Admiral King took the

lead in presenting the U.S. case for the Pacific war-an acknowledgment by

the Army of the Navy's primary interest in the Pacific. Nevertheless, in

backing the case for the Pacific position, Marshall was not unmindful of

the Army's interests. Ever conscious of the need to link Pacific and

European strategy, he sought, insofar as possible, to safeguard the plans

and projects of Generals MacArthur and Stilwell for their respective

theaters.

The Search for a Long-Range Plan

The basis for discussion of the Pacific war at QUADRANT was the over-all

plan

[230]

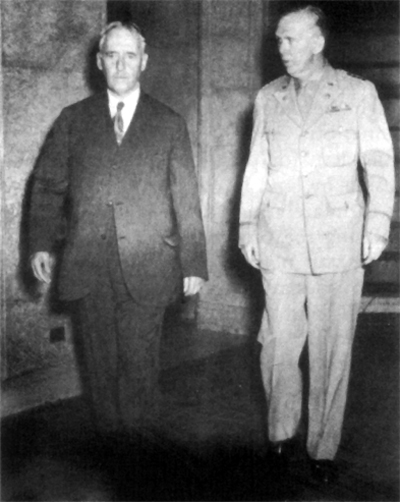

SECRETARY OF WAR HENRY L. STIMSON AND GENERAL MARSHALL at Château

Frontenac, 23 August 1943.

produced by members of the Combined Planning Staffs on the eve of the

conference.54 The initial reaction of the JCS to this combined effort had

been unenthusiastic, for they agreed generally that it overlooked many

possible elements that might shorten the conflict.55 The American Chiefs'

distaste for any plan that might prolong the war until 1947 or 1948 was

keynoted by King and Marshall in the second meeting of the CCS at Quebec.

King told the Combined Chiefs that the current lack of means in the

Pacific to carry out operations directed toward Rabaul CARTWHEEL) was

occasioned by Allied failure to consider the war against the enemy powers

as a whole. Reverting to the mathematical approach of which he was

evidently quite fond, he declared that if 15 percent of all Allied

resources were now deployed against Japan, then an increase to 20 percent,

or just 5 percent, would make one-third more resources available. The

resulting decrease in resources available in the European war would amount

to a mere 6 percent of the total. King and Leahy both thought it was most

important to plan how to transfer the bulk of Allied forces from Europe

to the Pacific-Far East once Germany was defeated. Marshall then went on

to point out that not only were all operations in the Pacific related to

those in Burma, but also affirmed that it was

. . . essential to link Pacific and European strategy. Movements of ships

from the Mediterranean must take place in the next few days if operations

from India were not to be delayed, and a decision must be taken. It was

important that no time should be lost in agreeing on a general plan for

the defeat of Japan since the collapse of Germany would impose the problem

of partial demobilization and a growing impatience would ensue throughout

the United States for the rapid defeat of Japan.56

Since the British would be faced with an even greater demand for

demobilization as a result of their long participation in the war,

Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff were perfectly amenable to the

early completion of a general plan for the war against Japan. They

realized that the future role of Great Britain in the struggle would

vitally affect British demobilization, particularly that of the ground

forces. Since British land forces would probably be substantially de-

[231]

SECRETARY OF WAR HENRY L. STIMSON AND GENERAL MARSHALL at Château

Frontenac, 23 August 1943.

produced by members of the Combined Planning Staffs on the eve of the

conference.54 The initial reaction of the JCS to this combined effort had

been unenthusiastic, for they agreed generally that it overlooked many

possible elements that might shorten the conflict.55 The American Chiefs'

distaste for any plan that might prolong the war until 1947 or 1948 was

keynoted by King and Marshall in the second meeting of the CCS at Quebec.

King told the Combined Chiefs that the current lack of means in the

Pacific to carry out operations directed toward Rabaul CARTWHEEL) was

occasioned by Allied failure to consider the war against the enemy powers

as a whole. Reverting to the mathematical approach of which he was

evidently quite fond, he declared that if 15 percent of all Allied

resources were now deployed against Japan, then an increase to 20 percent,

or just 5 percent, would make one-third more resources available. The

resulting decrease in resources available in the European war would amount

to a mere 6 percent of the total. King and Leahy both thought it was most

important to plan how to transfer the bulk of Allied forces from Europe

to the Pacific-Far East once Germany was defeated. Marshall then went on

to point out that not only were all operations in the Pacific related to

those in Burma, but also affirmed that it was

. . . essential to link Pacific and European strategy. Movements of ships

from the Mediterranean must take place in the next few days if operations

from India were not to be delayed, and a decision must be taken. It was

important that no time should be lost in agreeing on a general plan for

the defeat of Japan since the collapse of Germany would impose the problem

of partial demobilization and a growing impatience would ensue throughout

the United States for the rapid defeat of Japan.56

Since the British would be faced with an even greater demand for

demobilization as a result of their long participation in the war,

Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff were perfectly amenable to the

early completion of a general plan for the war against Japan. They

realized that the future role of Great Britain in the struggle would

vitally affect British demobilization, particularly that of the ground

forces. Since British land forces would probably be substantially de-

[231]

creased after the defeat of Germany, the British desired to base their

main contribution to the war against Japan on air and naval units. They

hoped that Japan might be defeated by sea and air attack alone, but they

agreed with the Americans that, for planning purposes, an invasion by land

forces should be assumed as ultimately necessary.57

Using the proposed over-all plan as a basis, staff planners moved to

define for the consideration of the CCS the points at issue and those on

which the Americans and British agreed. American planners condemned the

proposed schedule of operations in the Pacific as being too slow and

suggested that the tempo be pitched to defeat Japan within twelve months

of the fall of Germany. Although their British counterparts agreed on

acceleration, they would not accept the twelve-month limit. Both staffs

felt that the reorientation of forces toward the Pacific should be started

about four to six months before the fall of Germany. They also agreed on

an American advance toward Japan via the Central and Southwest Pacific

and possibly the Northwest Pacific, and on a British drive via the Strait

of Malacca and South China Sea, together with the development of a U.S.

line of supply to China through Burma.58

Perhaps the sharpest difference of opinion between the British and U.S.

planners revolved around the sequence and timing of the operations to take

south Burma and Singapore. The Americans believed that south Burma should

be cleared right after north Burma and visualized a target date of

November 1944 for tile beginning of south Burma operations. The British,

on the other hand, maintained that after the seizure of north Burma,

south Burma should be bypassed until November 1946 and that an effort to

take Singapore should be made in 1945.59 Wedemeyer

advised the JCS that tile long period of inactivity between the close of

north Burma operations (May 1944) and the initiation of the Singapore

campaign (March 1945) would result in too great a time lag. Furthermore,

operations in south Burma would provide more direct aid to China.60

The conflicting views between the two staffs were further complicated by

Churchill. He sided with the United States in disapproving a Singapore

expedition in 1945, since he did not think that the period from May 1944

to March 1945 should be a time of inaction. Instead, he wanted a move to

take the northwestern tip of Sumatra-his favorite Far Eastern operation,

which he pictured as the TORCH of the Indian Ocean and possibly of as

great strategic significance as the Dardanelles operation of 1915. The

Prime Minister received little comfort from the President in this

direction, for Roosevelt looked at the problem from another angle:

The position occupied by the Japanese might be compared to a slice of pie,

with Japan at the apex, and with the island barrier forming the outside

crust. One side of the piece of pie passed through Burma, the other led

down to the Solomons. He

[232]

quite saw the advantages of an attack on Sumatra, but he doubted whether

there were sufficient resources to allow of both the opening of the Burma

Road and the attack on Sumatra. He would rather see all resources

concentrated on the Burma Road, which represented the shortest line

through China to Japan. He favored attacks which would aim at hitting the

edge of the pie as near to the apex as possible, rather than attacks which

nibbled at the crust.

61

The JCS were willing to forego any definite decision on the south

Burma-Singapore question until the next conference, but pressed for the

acceptance of the twelve-month target date. In support of their belief in

a shorter war, they presented an AAF plan for the defeat of Japan, based

upon the use of the new very long range (VLR) bomber-the B-29

Super fortress-which was due to become available in quantity in 1944. The

1,500-mile tactical radius of this new weapon would allow it to reach most

of the important targets in Japan proper, if it operated from bases in the Changsha area in China, and its bomb load of ten tons would permit greater

destruction to be inflicted by each plane. Since the Air plan was so

recent that even the U.S. staff had not had a chance to study it

carefully, the CCS referred it to the Combined Staff Planners for close

consideration. In as much as use of Chinese air bases was part of the plan,

the JCS recommended that the TRIDENT decisions regarding China's

importance as an ally be reaffirmed and the capacity of air route to China

be expanded. In the meantime, studies could be made of the possibility of

operations at Moulmein in

Burma and on the Kra Isthmus of the Malay Peninsula to isolate Rangoon-the

gateway to north Burma and the Burma Road-and to facilitate the capture of

Singapore. As to the Pacific, they urged that the U.S. plan for operations

in 1943-44 be accepted in toto.62

The British met the American proposals more than halfway. Since Japan

depended so heavily upon airpower, naval strength, and shipping to

maintain its position, the CCS decided that greater emphasis should be

placed upon attrition and that greater use should be made of the Allied

air forces for this purpose. Through the build-up of the air route to

China, the employment of lightly equipped, air-supported jungle troops,

and the use of special equipment such as HABAKKUKS and artificial harbors,

increased advantages might accrue to the Allies.63 The British accepted

the twelve-month target date for future planning, but on the condition

that the reorientation of forces toward the Pacific

[233]

should proceed as soon as the German situation, in the opinion of the CCS,

would so allow. Forces for the operations in the Pacific would be

provided by the United States and those for the prospective operations in

the Southeast Asia area by the British, except for special types available

only to the United States. In the Pacific, as customary at the

conferences, the U.S. schedule of operations was approved. Operations in

north Burma would be carried out in February 1944, but the need for the

amphibious landings at Akyab and Ramree would be investigated further. The

CCS directed that studies be made on the south Burma-Singapore and

Malaya-Sumatra operations. They also decided to examine fully the

possibilities of developing the air route to China on a scale that would

permit the use of the bombers and transports available after the defeat of

Germany.64

The anxiety of the British to assure themselves of a proper place in the

later stages of the war-an issue that led to heated staff discussion-was

assuaged by assigning to the Combined planners the task of investigating

further operations in which the British would play the major role.

Evidently the Prime Minister was well satisfied that any doubts regarding

Britain's desire to share in the final defeat of Japan had been

effectively removed at QUADRANT-65

To the Americans, however, the perplexing problem of how and where to use

the British naval and air forces in an area where bases were few and

logistical difficulties many required answers that, at the moment, they

felt in no position to provide.66

Although only certain features of the over-all plan were adopted by the

CCS, there were several developments of especial significance. The

acceptance of the twelve-month target date promised to shorten the war and

to alter radically the timing and possibly the sequence of forthcoming

operations. Similarly, the free hand given to the United States in the

Pacific to conduct Southwest and Central Pacific offensives simultaneously

promised to move the war into higher gear. The main portions of the

over-all plan agreed upon by the CCS were essentially the short-term

phases indicating immediate directions without committing the Allies to

any definite ultimate roads. The relative importance of the different

approaches to Japan-land, sea, and air-and the selection of the main line

of offense for an invasion of Japan, if this should prove necessary, had

not been considered. It remained to be seen whether this inability to

determine conclusively where the weight of the Allied drive should be

placed and which operations should be held as subsidiary foreshadowed the

same prolonged deliberations on Pacific strategy as had marked the

planning of European strategy.

Pacific and Far Eastern Operations

1943-44

The American decision to open up a new line of advance in the Central

Pacific with the Gilberts-Marshalls operations in the fall and winter of

1943-44 was received by the British without protest. This increase of

pressure upon the

[234]

Japanese from the east, which would utilize the expanding U.S. naval

forces profitably, made a favorable impression upon Churchill, who

disliked the idea of fighting difficult land campaigns in Burma and China.

Nevertheless, the British Chiefs at first did question the necessity for

pressing forward in the Central Pacific and the Southwest Pacific with

equal vigor and suggested that the New Guinea phase be limited to a

holding operation, while the main effort took place through the mandated

islands. Thus, they observed, resources might be released for OVERLORD.67

Admiral King attacked this proposal at once, holding that if there were

resources that could be spared from the Southwest Pacific, they should be

sent to the Central Pacific. He stated that he himself considered both

advances essential, and Marshall pointed out to the British that the

troops and resources for the New Guinea operations were already in or en

route to the theater.68 The British did not press the point further.

Since the British seemed to have no other objections to the American plan,

the CCS approved the U.S. proposals to proceed successively through the

Gilberts, Marshalls, Ponape, Truk, and the Palaus to the Marianas in

1943-44. Consideration was also to be given to operations against Paramushiro in the Kurils. In the Southwest Pacific, eastern New Guinea as

far as Wewak, the Admiralty Islands, and the Bismarck Archipelago were to

be seized. As foreshadowed before the conference, Rabaul was to be

neutralized rather than captured.

69 With these operations accomplished, a

further move westward along the New Guinea coast to the Vogelkop Peninsula

was to be made in step-by-step, airborne-waterborne advances.70 The

decision to neutralize Rabaul marked the first official pronouncement of

a policy of bypassing strong centers of resistance and foreshadowed the

gradual replacement of the earlier conservative step-by-step method of

operations in the Pacific.

In the CBI, the long wrangle over the importance of China and the value of

capturing all of Burma came in for a full show of attention. The British

appeared perfectly willing to carry out the north Burma campaign, but

balked at the need for next clearing south Burma and were disinclined to

go through with the amphibious landings at Akyab and Ramree. In fact, on

several occasions the Prime Minister flatly opposed any commitment to

conduct the latter and warned his Chiefs of Staff against taking any

decision that he might later have to overrule.71

The JCS and the President had agreed before the conference that the Burma

campaign should not be delayed, and Roosevelt had even gone so far as to

mention the substitution of American resources and ships and possibly two

U.S. divisions, should the British seek to withhold forces and supplies

for use in their Mediterranean ventures.72 Marshall and

[235]

King had then been particularly disturbed by the unilateral action taken

by the British in the form of their "stand-fast order" preventing the

scheduled departure of resources from the Mediterranean to the CBI. At

the conference the JCS exerted considerable pressure on their British

colleagues in support of the land campaign to take all of Burma. They

pointed out the necessity of support for China, which ultimately would

provide the necessary facilities for the huge air forces to be released

for use against Japan after the defeat of Germany. To Marshall there

appeared to be four issues to be decided: (1) the value of Chinese troops

to future operations; (2) the likelihood that the existing Chinese

Government might fall if there were no sustaining action; (3) the

possible Japanese reaction to heavy air attacks; and (4) the need for a

port on the China coast. The road to China would not be opened, he felt,

by a Sumatra operation, but only through the capture of all of Burma,

including Akyab and Ramree.73

The British were not convinced that the reconquest of south Burma was a

prerequisite to assisting China, since they believed that the air route

could be developed to the degree that it could supply most of the numerous

Allied air forces that would become available for the CBI after Germany's

defeat. Marshall agreed that, in view of the great difficulties of

undertaking ground operations in the CBI, full advantage should be taken

of the Allied air superiority. In the matter of Akyab and Ramree operations, however, the British were reluctant to make any decisions.74

In the face of this indisposition on the part of the British Chiefs, the

intransigence of the Prime Minister, and the lack of Presidential

enthusiasm for Akyab and Ramree operations, Marshall admitted to the JCS

that he himself considered the plan for the landings unrealistic, since

the British seemed unable to produce enough efficient troops to ensure

success. The possibility of withdrawing some of the better-led Indian

divisions from the Mediterranean was considered by the JCS, but the

shipping implications for OVERLORD and the Pacific made such a move of

doubtful value.75

Nature took a hand in the fate of Burma operations at this juncture, for Auchinleck reported that severe floods in Assam might force the

cancellation of either the Ledo or the Imphal advance, and perhaps both.

Even without the interference of nature, the limited capacity and

inefficient operation of the Assam railroad promised to make difficult

logistical support of the land campaigns in Burma. The strains on the

Assam line of communications spurred the CCS decision to expand the

railway capacity, and to lay gasoline pipelines between Calcutta and

Kunming.76

The possibility of tonnage deficiencies in Assam led the British Chiefs of

Staff to suggest that a policy decision be made on the priority of

resources for undertakings in the CBI. They felt that the priority system

should not be a rigid one. Nevertheless, they favored putting the

[236]

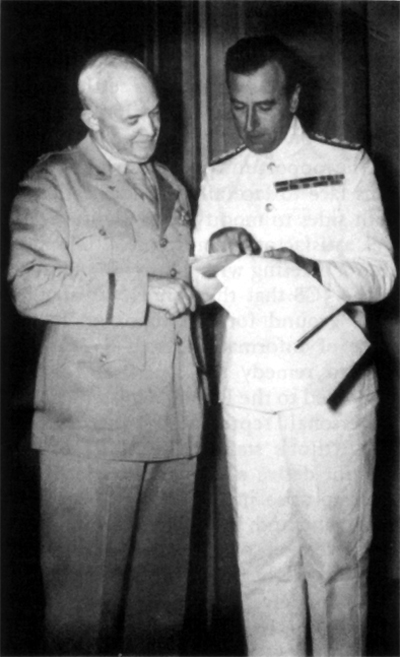

GENERAL ARNOLD WITH LORD LOUIS MOUNTBATTEN, Quebec conference, 20

August 1943.

main stress on north Burma operations, so necessary to establish land

communications with and to improve and secure the air route to China.

This primary emphasis on north Burma operations would serve as a guide

for the supreme commander of the Southeast Asia Command -still to be

appointed-. The commander would, of course, also have to keep in mind the

importance of long-range development of the Assam line of

communications, so fundamental for all CBI undertakings. Although the JCS

recognized that the proposed priority might affect adversely the supply

delivery to China over the Hump, they accepted the British

recommendations.77

Logistical difficulties involved in supporting both the air effort and the

projected ground offensive in China, which the TRIDENT decisions had

failed to appraise adequately, had to be faced more realistically at

QUADRANT. Despite British and Chinese preference for more emphasis on the

air build-up, the end result was an apparent reversal of the priorities

set up at TRIDENT. After the enthusiasm for the Chennault air plan that

had been so manifest at TRIDENT, this volte-face seemed to be a major

change in policy in the CBI. How strictly the reversal would be adhered to

in the future remained a matter of conjecture, for although the

unimpressive showing made by the air forces in China during the summer may

have influenced the President to give the Stilwell-Marshall-Stimson school

a chance to demonstrate the efficacy of a ground approach to aiding China,