| In Incorporation of America, Trachtenberg articulates the move to create a unified, nationalized, ordered public after the Civil War through the creation and manipulation of the public sphere. At the same time this was going on in the North in projects such as White City, Central Park, and Pullman City and throughout the nation in museums, department stores, and railroad stations, a major movement toward creating a distinctly Southern public and public sphere was also going on in the South. While projects in the North and throughout the nation aimed at reconciliation, order, and unification (the monuments included), the increased proliferation of the solitary soldier monument throughout the South from the end of the war into the first two decades of the twentieth-century, perpetuated and created divisions, tensions, and differences in class, gender, and region within the public sphere. |  |

|

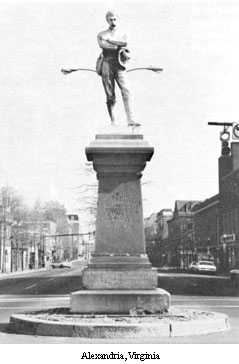

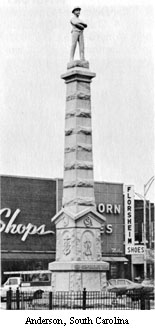

I sought to show in this project how much of a monument's meaning resides in its historical context and to access some of that meaning by restoring some of this context. Much of that meaning has necessarily been divorced from the monument by time and circumstance. The solitary soldier monuments are, in a sense, quite different objects from what they were at the time of their dedications. Inscriptions identify the statues and give them a minimal context, but much of their original meanings and significance have been lost. Nor could they have been expected to endure. This speaks to the primacy of the monument's role as a point for people to gather around and become a community. A monument is a fairly limited medium in terms of what it can express. However, it does have one extremely important characteristic, and that is its placement in the public sphere. Such placement endows it with the power to articulate important ideas such as definitions of nationhood, power, public, and identity. Thus, the monument endures as a reminder to people of the conflict of the Civil War and the sublimation of the Old South and Confederate Cause. It endures as a voice of Southern identity, difference, and regionalism in a collective of united states. |

In shaping the course of my research I had to leave some rich areas of study behind and was unable to get to others. The following is a list of such topics and activities:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|