everyone says one ought to sell all one has and mortgage one's soul to go there; it is esteemed such a revelation of beauty. People cast away all sin and baseness, burst into tears and grow religious etc., under the influence!!1

| In his study of the gilded age, The Incorporation of America, Alan Trachtenberg reveals the emergence of a new public sphere. Rapid expansion of industrialization created cities of a new sort; it created the metropolis. Growth in industry caused more and more people to forsake small businesses and agrarianism for employment in the cities. |

| At the same time, advances in technology created a world of business and industry increasingly dominated by the machine, as it replaced workers in the performance of labor. This created a new class of unskilled laborers on the one hand, and a class of specialized engineers and trained technicians on the other. Offering greater prospects for profit, the machine put management in the hands of a corporation of investors and made productivity the keynote of management. This resulted in compartmentalized labor and factory spaces, greater regulation of work hours, activities and behaviors. It also resulted in tensions between the managing and working classes, epitomized by the creation of labor unions and the violent labor strikes of the time period. Thus, industrialization and incorporation not only promoted the growth of population, and thus of the city as well, but it also created a decidedly mechanized, regulated, stratified, and strained business and labor situation which was manifested in the social and physical conditions of the city. |

|

|

For example, poverty and crime increased and became increasingly visible. Political corruption loomed large as did friction between the classes of management and labor and the rich and poor. The labor strike of 1877 alone resulted in over one hundred deaths. In addition to such violence, technology provided ample dangers as well. At work, powerful equipment coupled with fast-paced production resulted in accident and injury, while "exploding gas mains and inflammable electrical wires"2 made the city a veritable jungle. The city took on the aspect of a living force with power over the people within it. Recognizing such power, people also saw in the city a means of reforming not only the city itself, but its citizens as well, including their health, happiness, and morality. This attitude marks a new conception of the public sphere as that which can create and shape a public. It was thought that by creating order in people's environment, even the most superficial aspects of the environment, such as its appearance, a social, political, and moral order would result. In short, this attitude marks the identification of the public sphere as a public sphere. This new attitude was behind the call for street lamps, parks, and better sanitation. It was the principle behind the social engineering of Olmstead's Central Park, the palatial movie theaters, railroad stations, museums, department stores, and Pullman city, but was epitomized by the White City in the World's Fair of 1893, the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The Columbian Exposition defined the public sphere for a whole nation, drawing over 27 million people, almost one quarter of the country's population at the time. Those unable to attend experienced the Fair through newspaper accounts, photographic guidebooks and post cards, and through the accounts of those who did visit.3 The size of the fair, and its dissemination into the nation through word and photograph, indicated right away that the public sphere was national. Like the palatial railroad terminals, movie theaters, and department stores of the time, the Fair was designed for the masses. From the transportation arrangements, to ticket prices, to the nature of the exhibits, the Fair was designed to attract and accomodate a large number of diverse people. The department stores and movie theaters offered luxury to the masses, a luxury for all classes, by virtue of its manifestation in a public building and venue. White City offered not only luxury for the masses, but a lesson in culture as well. Epitomizing social engineering, the motto of the fair was "Not Matter, But Mind; Not Things, But Men", suggesting the primacy of intelligence and morality over objects and experience. This motto also expresses the doctrine that there is a separation between the realm of labor and science and the realm of art by calling for the supremacy of culture and art, represented by the Mind and Men, over science, industry, and labor, represented by Matter and Things. This was expressed in the organization of the exhibit spaces which were categorized and separated according to this distinction. Yet, the relation is more complex. The motto and the fair also suggest a certain fusion between art, science, and labor. As Trachtenberg states:

...art provided the mode of presentation, the vehicle, the medium through which material progress manifests itself, and manifests itself precisely as serving the same goals as art: the progress of the human spirit.4

|

|

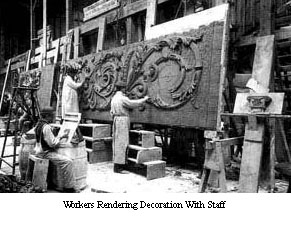

| This relationship between art and science and labor was expressed particularly in the buildings of White City's Court of Honor which lay at the center of the Fair. These buildings were of a neoclassical style, large, white, and imposing with columns and ornamented pediments. Yet, within these structures were exhibits on science, industry, and labor. Furthermore, the neoclassical style was just that, style, as opposed to structure. For, the neoclassical architecture was not really architecture but the image of architecture created by applying a plaster-like material called "staff" to the structures of the Court of Honor. The staff was then painted white to emulate marble. |

|

| The structures of the buildings were really an achievement in steel. Thus, White City teaches the lesson that science and industry are validated in so far as they contribute to culture and the progress of humanity. They are given a place in the public sphere, but it is subordinate to, and clothed in, the form of culture. |

|

|

|

This use of neoclassical architecture ultimately depicts the public sphere as monolithic. First, it

defines the public good as culture and progress. More fundamentally, it defines the public as an

ideal "humanity". This has a leveling, homogenizing effect on class, racial, and regional

distinctions. In subordinating labor to culture, White City creates, or affirms the separation

between the unskilled laboring class and the classes of managers and trained workers with

specialized skills. At the same time, White City seeks to deny or override this and all other

distinctions by defining the public as an idealized mass unified by the goal of culture and progress.

White City's definition of the public and the public sphere is undeniably homogenized and

nationalistic.

The unified style of White City manifests the rule of a single authority. That authority was the "World's Columbian Commission", a private corporation created by state legislation which raised money for the Fair by selling stock. Trachtenberg points out that the Official Manual of the Fair included a list of the Commission's bylaws, of its board of directors and committees, a list of "prominent Chicago citizens among its ranks", and a copy of the Act of Congress which gave the Commission responsibility for the Fair.5 The content of the Manual celebrates the absolute power of an elite group consisting, primarily, of businessmen, bankers, and lawyers. Thus, White City defines public authority as an elite and private group of middle to upper class men who had both money and the support of a government that transmitted its responsibility, power, and authority to the Commission through legislative acts. White City further identifies authority with the government through its neoclassical architecture; classical architecture had been used throughout time to accommodate and symbolize the government, its activities, and power. Furthermore, the central location of White City in the spacial arrangement of the Fair as a whole suggests that the government is the center of society and the public sphere. While the planners of White City wanted authority to go by the name of culture and progress expressed in the neoclassical facade of its Court of Honor, they also wanted to define authority as belonging to the government, to private corporations, to the power of money, and to an elite group of middle to upper class professionals. Nor does White City exclude business or science from its vision of authority. While the exterior of the buildings offered a uniform picture of culture, the interiors of the buildings were dedicated to business and advertising in the guise of informational and entertaining exhibits and displays. Exhibits did as much for business as they did for the delight of their audience. Similarly, while the neoclassical facades were meant to disguise the steel structures supporting them and the technological exhibits within them, they remained, nonetheless, facades and disguises. Visitors to the Fair were meant to see the wonder of the engineering feat that upheld the face of culture. |

|

|

Among the more visible and celebrated scientific and technological exhibits were an enormous elevated traveling crane and a 2,000 horsepower engine which lit 10,000 incandescent lights. According to Trachtenberg, "The use of alternating-current electrical power to illuminate the entire fairgrounds was one of the event's unique achievements."6 While subordinate to culture and progress, business and science were both represented as invaluable to them as well. Thus, the public sphere belonged to the authority of business and science as well as to the government and incorporation. |

|

The incongruity between the facades of the buildings and their structures and activities also marks

the public sphere as a place of disparity, appearances, and illusion. These are, in fact, at the heart

of the principle of social engineering which is essentially based on a distinction between appearances and reality. Yet,

the Fair does more than simply separate the two. As Miles Orvell contends

in The Real Thing, the

relationship between appearances and reality and the very meanings of authenticity and reality

were called into question during the Gilded Age by new technologies of

imitation.7

More than simply evincing these quandaries, the Fair presents a solution to them through the

medium of the public sphere. White City suggests that, by manipulating appearances, reality may

be changed as well. Thus, appearances and the ideal they represent are more powerful and, in a

sense, more real than reality.

White City teaches that manipulation of appearances is a tool of power and authority, a tactic by which to create and control. It also offers a definition of reality as that which is ideal. Indeed, the whole overall effect of the Fair was to make the ideals of culture, business, technology, and their union an experienced reality for a significant portion of the American population. This was achieved by using the public sphere as a voice of authority and as an environment which completely surrounds the individual and defines their world. We find that White City reaffirms the bewildering power of the city over the people in the form of a public sphere that surrounds the visitor to the Fair with the overwhelming virtuality of a real city. And, like the metropolis, White City achieves this by dazzling the visitor as spectacle. White City was a spectacle in one sense because it represented itself as something virtual, as an ideal to be achieved, as a facade with a concealed structure and function. Furthermore, the whole illusory spectacle was created and maintained by an elite group and a mass of workers behind the scenes. The visitors themselves had nothing to do with the creation or maintenance of the spectacle. They were mere spectators in a world beyond their control. |

| White City was also a spectacle in the sense that its architecture, activities, and exhibits were designed to appeal to the visitor's sense of beauty, wonder, awe, and enjoyment. For, though I have emphasized the way in which the facades represented themselves as facades and were meant to be seen as facades, they were also meant to work as facades. They were meant to distract from other realities and meanings of the fair, such as the separation of the labor class and its centrality to the success of the Fair on the one hand, and its exclusion as a class from the vision of ideal society on the other. Thus, White City presents the public sphere as a sphere of spectacle and powerless spectators. Yet, unlike the spectacle of the metropolis seen as an autonomous force, White City is a spectacle created by a powerful elite, manipulated for the good of humanity (also, incidentally, defined by the interests of the elite). |

|

| White City represents a definitive moment in American history, when a powerful voice from within attempted to define America as the ideal of culture and progress, the people and public as a homogenous, manipulatable mass, the nation as a unified and monolithic whole, authority as a union of culture, business, science, and government, and reality as an orderly and beautiful ideal. The moment marked the public sphere as a medium and arena for manipulation, domination, and creation of the public and reality. It marked the sphere as the territory of power and authority. This is also the moment when the public sphere transcended spatial boundaries to accommodate the masses who could not attend, through newspapers and photographs, residing ultimately in not only these words and images, but also in the thought and opinion of a growing and increasingly accessible public. The mechanization, industrialization, and incorporation of America created a new kind of experience which necessitated the creation of a public sphere that, in the form of White City, reflects the domination of those powers which called it into being. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|