Chapter XII

WAC Center and WAC School

Nowhere were the changes shaking the

Corps felt more severely than at the heart of the training program, the WAC

Center and WAC School. The 1954 move from Fort Lee to Fort McClellan had placed

these organizations under the jurisdiction of the commanding general of the

Third U.S. Army, Fort McPherson, Georgia. The WAC Center commander's immediate

supervisor, however, was the post commander at Fort McClellan, and doctrine

and policy for enlisted and officer courses came from the Continental Army Command,

Fort Monroe, Virginia. Within that organizational structure, the training of

new officers and enlisted women had flourished.1

The WAC Training Battalion processed

basic trainees, reenlistees, and reservists as it had done at Fort Lee. The

WAC School operated the basic and advanced courses for officers and added a

typing and clerical procedures course and a stenography course. In 1957 the

WAC College Junior Course, too, became part of the curriculum. Headquarters

and Headquarters Company housed and administered the enlisted women who worked

throughout the WAC area and at post headquarters, Noble Army Hospital, the dental

clinic, and the Chemical Corps Training Command. The 14th Army Band (WAC) housed

and administered its members. The WAC Center commander controlled and directed

all four activities. To staff them and her own headquarters, she had approximately

100 officers and 260 enlisted women but no civilians. Except for the periods

of WAC expansion-1967, for Vietnam, and 1972, for the all-volunteer Army-few

changes occurred in these figures.2

After moving into their initial 21-building

complex, the WACs had made the area their own. To mark the 27 September 1954

dedication of the center and school, the WAC Officers Association installed

a large plaque mounted on a marble slab in a triangular area between the parade

[329]

ground and the site of the WAC chapel.

The WAC detachment in Japan contributed a Japanese stone lantern in October

1956, and it was placed in this area, known as the WAC Triangle.3

A ground-breaking ceremony for the WAC

chapel on 18 June 1955 had brought Brig. Gen. Frank Tobey, Chief of Chaplains,

and Col. Irene O. Galloway, DWAC, to the center. The chaplains at Fort McClellan

provided a silver-plated spade for the event and later presented it to the WAC

Museum. A few months later, on 28 September, at the ceremony for the laying

of the cornerstone, a copper box containing items used by WACs was encased in

the stone. The WAC detachments in the Fifth Army area donated a set of canto

chimes to the chapel and Chapter 1, Chicago, WAC Veterans' Association, contributed

a bronze dedication plaque, unveiled at the dedication on 12 May 1956. Several

years later (1964), the then chief of chaplains, Maj. Gen. Charles E. Brown,

Jr., allotted $20,000 from the Chaplains' Fund to install stained-glass windows

in the chapel-the high, stained-glass window in the back of the chapel includes

a large Pallas Athene insignia and the coat of arms of the WAC School.4

Because of its large seating capacity, the chapel became the site of orientation

and graduation exercises for basic trainees, clerical students, and student

officers. And, even though attendance at church services was voluntary, the

chapel attracted capacity crowds. Enlisted men found the chapel a pleasant place

to attend services and to become acquainted with the women. On 4 November 1978,

the post commander (Maj. Gen. Mary E. Clarke) issued a general order officially

naming the chapel the WAC Memorial Chapel. 5

The post engineers added a reviewing

stand to the WAC parade ground in October 1958 in time for a regimental parade

welcoming the visit of Col. Kim Hyun Sook, Director, Women's Army Corps, Republic

of Korea. In 1960, the parade ground was named in honor of General of the Army

George C. Marshall, who had requested the formation of the Corps in 1941. The

next year, the engineers built a corner fence made of native Alabama fieldstone

on the southwestern edge of the parade ground for the name plaque, "George

C. Marshall Parade Ground."6

Buildings and other landmarks honored

the memory of other individuals who had contributed to the success of the WAC.

WAC School Headquarters (Building 1081) was named for Brig. Gen. Don C. Faith,

who had commanded the First and Second WAAC Training Centers at

[330]

Fort Des Moines and at Daytona Beach,

as well as the WAAC Training Command, during World War II. General Faith's widow,

Katherine Faith, attended the ceremony on 23 November 1963. The serenity of

the event was marred by the news of the death of John F. Kennedy. A memorial

service for the president had been held at the chapel on the night of the 22d.7

On 13 May 1957, Rice Road, running from

Fort McClellan's North Gate to WAC Center Headquarters (Building 1060), was

named for Lt. Col. Jessie P. Rice, the deputy director of the WAC from March

1944 to April 1945. In 1963, Col. Irene O. Galloway succumbed to cancer, and

Fort McClellan's North Gate and North Gate Road, which led directly into and

through the WAC area, were renamed Galloway Gate and Galloway Gate Road. The

only WAC to have a building named for her was Sgt. Maj. Florence G. Munson.

The headquarters and classroom building for the WAC Training Battalion (Building

2281) was dedicated in her honor on 29 October 1965. She died in 1964, after

serving as sergeant major of the battalion from 1959 to 1964. Through this process

of naming buildings and roads, bonds of tradition and shared memories gradually

enveloped the WAC site at Fort McClellan.8

In 1952, WAC officers at Fort Lee had

organized the WAC Officers Association as a nonappropriated fund activity (i.e.,

not supported by government funds) to raise funds to accomplish morale-building

projects. The association's members supported its projects through membership

dues, white elephant auctions, and fund-raising parties. The association moved

with WAC Center to Fort McClellan. In 1971, the group changed its name to the

WAC Association and accepted as members enlisted women in the top four grades.

For twenty-four years, the association served recreational, social, charitable,

and morale needs at WAC Center and School. It bought furniture, air conditioners,

cooking utensils, and other equipment to improve enlisted and junior officer

quarters, and it paid for nice-to-have items for special ceremonies and parties

for the women at WAC Center and School. Members dissolved the group in 1976

when the WAC Center and School deactivated and voted to transfer its assets

to the WAC Foundation to help construct the WAC Museum building. 9

[331]

Another organization that frequently

contributed to projects for increasing morale at the WAC Center and School was

the National WAC Veterans Association. The idea for this group came from the

National WAC Mothers Association that had chapters in sixty cities throughout

the United States during World War II. On 14 May 1946, a board appointed from

members of the Chicago chapter formed the Chicago WAC Veterans Association.

Women in Cleveland, Columbus, Milwaukee, and Pittsburgh soon followed the lead

of the Chicago veterans. Membership grew, and members held their first convention

in Cleveland in March 1947. Four years later, Lt. Col. Mary-Agnes Brown Groover,

a lawyer and a WAC reservist, presented the articles of incorporation for the

national association to Esther Bentley, the association's president. The National

WAC VETS Honor Guard, established in 1951, still regularly represents WAC veterans

at ceremonies in Washington and other cities throughout the United States. The

organization's bimonthly newsletter, the Channel, keeps members informed

not only of meetings, but of VA benefits, WAC activities, and other items of

interest.10

The WAC VETS Association promotes the

general welfare of all veterans but concentrates on assisting veterans of the

WAAC and the WAC, particularly those in adverse circumstances. Many chapters

devote their activities to providing services for veterans in Veterans Administration

hospitals. The association also supports a number of nonprofit organizations,

including the WAC Foundation; the WAC Veterans Redwood Memorial Grove, Big Basin

Redwoods State Park, California; the Hospitalized Veterans Writing Project (creative

writing for recreation and therapy); and the Cathedral in the Pines Memorial,

Ringe, New Hampshire, a memorial to the dead of World War II. On 30 October

1984, President Ronald Reagan signed H.R. 4966 giving the WAC VETS Association

a federal charter and national recognition as a veterans' organization. 11

The third organization of importance

to the WAC is the WAC Foundation, established as a nonprofit corporation under

the laws of the state of Alabama in July 1969. Authorized by the post commander

to operate at Fort McClellan, the WAC Foundation succeeded in raising almost

$400,000 to build the WAC Museum. After the building was constructed and dedicated

on 13 May 1977, the WAC Foundation gave it to the Army which now operates it

with government funds. The WAC Foundation continues to raise money to purchase

equipment and services for the WAC Museum and to educate the public on the past

and present role of women in the Army. It issues a biannual newsletter, the

Flagpole, and conducts a WAC Museum Reunion in May of every even year.12

[332]

In size and mission, WAC Center with

its subordinate activities WAC School, WAC Training Battalion, and Headquarters

and Headquarters Company-was the equivalent of a regiment or a brigade and was

organized along brigade lines. The 14th Army Band (WAC) belonged to Third Army

but, operationally, it also came under the center commander. The commander's

staff included a deputy commander, an S-1 (personnel officer) and adjutant;

an S-2 (intelligence officer) combined with the S-3 (training officer); an S-4

(supply officer); a management officer; and an information officer. The staff

developed and implemented plans and policies to manage and distribute the commander's

resources to perform her various missions. Each staff member had a counterpart

in the school, training battalion, and Headquarters and Headquarters Company.

Because of the need to encourage young officers to enter the Regular Army, and

to groom other Regular Army officers for the positions of director and deputy

director, WAC, the Corps usually filled the staff positions with regular rather

than with reserve officers on extended active duty. The WAC Center was the only

Army command of brigade size that required and assigned women in such staff

and command positions, and women prized assignment in them. Col. Dorotha J.

Garrison was the only reserve officer to command WAC Center (1970-1972).

WAC Center did differ from most Army

brigades in one way-it was commanded by a lieutenant colonel until 1968. After

the elimination of restrictions on women officers' promotions in 1967, the WAC

Center commander's position was elevated to the grade of colonel, along with

the positions of deputy commander of WAC Center and assistant commandant of

WAC School.

Few men filled WAC Center or WAC School

positions until 1973. Occasionally, male cooks worked in the mess halls, and

during one year (1962), a male NCO, Sgt. 1st Cl. Harold Fitzgerald, taught in

the WAC Typing and Clerical Procedures Course at WAC School. Only the chaplain

assigned to the WAC Center chapel provided a continuing male presence. The women

took great pride in their ability to operate the center and gave up these spaces

to men as reluctantly as men gave up such positions to women. Only the WAC expansion

that began in 1972 finally forced the center to requisition male NCOs to fill

vacancies. On 5 September 1973, the first male drill sergeants were assigned

to the 2d and 3d WAC Basic Training Battalions. In 1974, WAC Center accepted

its first male staff officers.13

[333]

LT. COL. ELEANORE

C. SULLIVAN (1952-1955) turns over command of WAC Center and WAC School,

Fort McClellan, to Lt. Col. F. Marie Clark (19551956) on 24 June 1955.

In the WAC hierarchy, the dual position

of commander of the WAC Center and commandant of the WAC School held importance

and prestige second only to the position of the director of the WAC. Of fifteen

WAC Center commanders between 1948 and 1976, two, Elizabeth P. Hoisington and

Mary E. Clarke, and one deputy commander, Mildred C. Bailey, advanced to the

director's position.14

Perhaps no WAC Center commander had

greater responsibilities than Lt. Col. Eleanore C. Sullivan. She and her staff

carried out the move to Fort McClellan, a job that included moving personnel

and equipment, commencing training at the new site, establishing community relations

in the Anniston area, entertaining hundreds of visitors at the new facility,

participating in parades and ceremonies, and keeping up the morale and welfare

of WACs at both sites. On 20 January 1955, the colors flew for the first time

from the flagpole at WAC Center headquarters. Colonel Sullivan also launched

a three-year landscape beautification program and

[334]

| LT.

COL. MARJORIE C. POWER |

|

LT. COL. LUCILE G. ODBERT |

established the WAC Museum. The museum

at first occupied one room of her headquarters building and later was moved

to a wing of the basic trainees' classroom building, where each trainee and

student could pass through and see photographs, uniforms, paintings, and documents

that told the history of their Corps.15

Lt. Col. F. Marie Clark, who succeeded

Colonel Sullivan in 1955, streamlined the organizational structure by eliminating

some duplicative positions in subordinate activities. She activated a reception

company in the WAC Training Battalion and gave it responsibility for welcoming,

orienting, outfitting, and processing newly arrived WAC recruits. Thus, for

the first time since World War II, the recruits entered a reception company

before being assigned to their basic training unit. Lack of space forced the

center to suspend this system in 1957, but in January 1963, it was revived with

the creation of Headquarters and Receiving Company, WAC Training Battalion.

These functions remained in the battalion until February 1973, when the post

commander activated the U.S. Army Reception Station.

[335]

In the spring of 1956, Colonel Clark

reintroduced WAC field training, which had been suspended since 1953, when heavy

storms destroyed the outdoor training area at Fort Lee. By far the most popular

phase of basic training, it taught recruits first aid, map reading, camouflage,

civil defense, and familiarity with the M 1 carbine. In 1961, field training

was expanded to include overnight exercises. Thereafter, unit commanders happily

noted that the women returned from field training with a greater feeling of

team spirit and will to succeed than they had had before.16

During Lt. Col. Frances M. Lathrope's

tour, field testing of the new Army green cord summer uniform began and fitting

tests got under way on the women's Army green winter uniform. Colonel Lathrope,

who served as WAC Center commander from 1956 to 1958, boosted the morale of

members of WAC Training Battalion's cadre and staff by allowing them to wear

a distinctive yellow cotton scarf with their winter duty uniform. Battalion

members became so fond of the scarf that in 1959, the then center commander,

Lt. Col. Lucile G. Odbert, obtained official approval for it. The College Junior

Program commenced at WAC School on 14 July 1957 as nineteen cadets entered the

first class. Also women officers of foreign military armies began attending

officer courses at WAC School beginning in August 1956. Between 1957 and 1972,

when the WAC Officer Basic Course was discontinued, 112 foreign students attended

the course as well.17

Between 1958 and 1960, the number of

recruits entering WAC basic training jumped from 2,715 to 3,220. As usual, the

input peaked between June and October, driving the trainee load over the programmed

level for these months-a challenge to Lt. Col. Marjorie C. Power, who commanded

WAC Center in 1958 and 1959. The WAC Center historian described the emergency.

"The housing shortage was only one of the problems. The battalion mess

had to feed in shifts. Training facilities were overtaxed and trainers overworked.

Battalion was forced to borrow personnel from Headquarters and Headquarters

Company and the WAC School to act as cadre."18

One of the major problems that Colonel Power encountered was the shortage of

the brown and white seersucker exercise suit. Both recruits and clerical training

students wore this uniform (shirt, shorts, skirt) to classes daily. As an emergency

measure, the quartermaster general substituted a blue exercise suit worn by

the WAFs. Later in 1958, the WACs' newly designed tan, three-piece, cotton exercise

suit became available and was issued at WAC Center. Thus, after

[336]

| LT.

COL. SUE LYNCH |

|

LT. COL. ELIZABETH H. BRANCH |

| COL.

SHIRLEY R HEINZE |

|

COL.

LORRAINE A. ROSSI |

[337]

1958, it was not unusual for a unit

in training to have women dressed in brown, blue, or tan. The combination led

some to describe the center's appearance as "molting." In March 1959,

the Army green cord summer uniform was issued, adding yet another shade to the

assortment of colors. A year later, however, uniformity returned. Trainees and

students now wore the tan exercise suit to classes and the green cord to parades

and inspections. At WAC School, Colonel Power shifted the emphasis from lecture

to student participation in the WAC Officer's Advanced Course and organized

a section to develop WAC training films for WAC basic trainee, clerical student,

and student officer courses.19

Colonel Power retired in September 1959

and was succeeded by Lt. Col. Lucile G. Odbert. To increase the prestige of

enlisted women, she enlarged the WAC NCO Advisory Council, which had been established

in November 1955, and included on it all WAC E-8s and E-9s assigned to Fort

McClellan. The senior NCO at WAC Center headquarters, in 1959 M. Sgt. Julia

Vargo, chaired the council. The council developed ideas to improve the operation

of WAC Center and WAC School, operated the WAC-of-the-Month program, and promoted

the sports program. The latter included intramural and regional competition

in softball, basketball, volleyball, golf, tennis, bowling, small games, and

marksmanship. WAC Center, with more women to select from, frequently won top

sports prizes within Third Army area. In 1960, for example, WAC Center won first

place in the Third Army Golf Tournament for the second consecutive year; 1st

Lt. Sallie L.E. Carroll won first place in the Slow Fire .22-Caliber Rifle Matches

at Tampa, Florida; and a team including Lieutenant Carroll, 1st Lt. Joyce W.

O'Claire, Sgt. 1st Cl. Marian C. Jamieson, and Sgt. Credessa W. Williams took

first place in the sharpshooter events at the Central Regional Pistol Matches

at Fort Knox, Kentucky, defeating male teams in the .22- and .45-caliber team

matches.

The advent of proficiency pay presented

a problem for women assigned as cadre and instructors at WAC Center because

they were not eligible for proficiency pay while in those positions. Colonel

Odbert set out to resolve the difficulty. In March 1960, she wrote to the adjutant

general (TAG), through channels, and asked that women who qualified for proficiency

pay in their primary MOSs be authorized to receive it while assigned at WAC

Center and WAC School. TAG denied the exception because it might invite others

and, instead, advised that women who would lose proficiency pay not be assigned

to the center. Colonel Odbert had already rejected that solution. Such a practice

would have excluded some of the best WAC NCOs and denied them promotion opportunities.

TAG tried to develop a standard MOS for WAC training cadre and military subject

instructors but, when this proved to be impractical, advised the center commander

to assign women in personnel and

[338]

administrative MOSS to the instructor

and cadre spaces. Most women held these MOSs and could continue to receive proficiency

pay if assigned in them. This complex arrangement continued until December 1971,

when the DCSPER authorized WACs to attend the Army Drill Sergeants School. There

WACs could earn the MOSS required for assignment to instructor and cadre spaces.20

Under the next center commander, Lt.

Col. Sue Lynch, the WAC School took a more prominent role in the formulation

of doctrine and policy in WAC training matters. An educator in civilian life,

Colonel Lynch broadened the faculty training program and improved the quality

of instructors and instruction at the center and school. Faculty members responded

by revising their lesson plans to present their material in more interesting

and more understandable ways and by improving their training aids. In May 1962,

CONARC gave WAC School the authority to approve changes in the basic training

program. In 1963, WAC Center hired its first civilian, a librarian for the WAC

School. Throughout the period, WAC School's Doctrine and Literature Division,

headed by Lt. Col. Mary Charlotte Lane, produced a prodigious amount of statistical

analyses, training films, historical studies, handbooks, and a text entitled

The Role of the WAC. When Colonel Lynch retired, she had served longer

as commander than anyone before or after her. Lt. Col. Elizabeth P. Hoisington

replaced her on 1 October 1964.21

Colonel Hoisington further improved

the training programs for recruits and student officers and the facilities at

the WAC Center. To the field training program she added a silent night march,

more realistic air defense and civil defense exercises, and a two-hour course

on unarmed self-defense. The latter served at least in part to replace the weapons

familiarization and firing course. That course had been deleted by CONARC from

the field training program in 1963 on the grounds that the new M14 rifle, which

had replaced the carbine and weighed one pound more, was too heavy for women.

That change had eliminated weapons training from the women's program. To the

Leadership Orientation Course, initiated in 1963 to develop leaders among recruits,

Colonel Hoisington added two more hours of theory; in 1973, the course was replaced

by the Special Leadership Program that had the same objectives. In March 1966,

CONARC introduced an Army training test (ATT 21-3, Individual Proficiency in

Basic Military Subjects, WAC) that measured the level of learning achieved by

each trainee in each basic training subject. And, also beginning in 1966, WAC

School accepted male stu-

[339]

RETREAT CEREMONY AT

HOISINGTON WALK, WAC CENTER, 30 July 1970. Brig. Gen. Elizabeth P. Hoisington

with Cols. Maxene B. Michl, Dorotha J. Garrison, and Georgia D. Hill (left

to right).

dents in the enlisted clerical courses

when class space was available. The men lived in barracks on main post but ate

their noon meal with the WACs.

At Colonel Hoisington's insistence,

the post commander built a cement walk down the steep incline from her headquarters

to the battalion area in November 1965. Officially named South Walk, the post

engineer put a sign at the bottom and unofficially designated it "Hoisington

Walk." But, in addition to introducing new ideas into the WAC Center and

the WAC School and causing new walkways to be built, Colonel Hoisington also

continued traditional activities such as march-out on Tuesday mornings, regimental

parades on Saturday mornings, WAC-of-the-Quarter (formerly of-the-Month) selections,

the annual WAC anniversary torchlight parade from the battalion to the Hilltop

Service Club, the WAC Drill Team, and the sports program. She added an Arbor

Day tree planting, a cost-

[340]

consciousness program, and a more active

social and sports program for the officers.22

In 1966, after Colonel Hoisington left

to become director of the WAC, Lt. Col. Elizabeth H. Branch, then assistant

commandant of the WAC School, replaced her. A new discharge regulation issued

that year created disciplinary problems from which the center had virtually

been free since it opened. The new regulation required recruits who were unsuitable

for additional training to be "recycled" (turned back to repeat their

earlier training) before any discharge action could be initiated. Heretofore,

the battalion commander had decided whether a recruit's performance and attitude

warranted additional training. When the new regulation was implemented at WAC

Center, many of those scheduled for recycling went AWOL rather than participate

in additional training when all they wanted from the Army was a discharge. The

WAC Center historian wrote: "The AWOL rate among WAC trainees was negligible

from January through July 1966 (.31 %). Upon implementation of the new recycling

requirement, it rose to . . . 18.7%."23

The AWOL rate continued to rise, and Colonel Branch recommended, through channels,

that the regulation be modified so that recycling could be waived for obstreperous

or unmotivated trainees. The Department of the Army agreed, and in October 1968,

the regulation was revised so that, upon the recommendation of a judge advocate

general, the commander could waive counseling and recycling procedures for certain

recruits. The WAC Center's AWOL rate fell from 31 percent to 8.3 percent for

the third quarter of 1968 and to 2.26 percent in the fourth quarter.24

Secretary of the Army Resor's decision

in May 1967 to increase WAC strength by 35 percent to support the Vietnam War

had caused the number of new arrivals to soar at the WAC Center and WAC School.

Throughout her tenure, Colonel Branch and her staff continuously developed and

revised plans to train more recruits, clerical students, and officers than ever

before. The addition of another basic training company (Company E) in 1968 relieved

overcrowding, but, throughout this period, the instructors and cadre had to

manage double loads of recruits and students. A WAC NCO Leadership Course was

inaugurated at WAC School in January 1968 to obtain more trained NCO leaders

for duty at Fort McClellan and in the WAC field detachments. This four-week

course prepared women in grades E-4 and above as cadre and as supervisors. The

training battalion dining hall that could seat 400 women at one time began operating

on shifts during the summer and set a record on 1 September 1968 by feeding

1,340 women at one meal. The Headquarters

[340]

and Headquarters Company mess hall frequently

fed the overflow from the training battalion dining ha11.25

Despite expansion problems, the WAC

Center celebrated some special occasions in 1967. Over thirty members of the

DACOWITS arrived in April to tour the facilities. They were followed by a training

inspection team from Third Army that reported "instructor and supervisory

personnel [at WAC School] were both knowledgeable and enthusiastic," and

that "the heavy training overload is being managed effectively . . . [with]

no adverse effect on the quality of training."26

On 14 May, four WAC directors, Colonels Hallaren, Rasmuson, Gorman, and Hoisington,

joined a week-long celebration marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Corps.

Highlighting these events was a retreat ceremony at the foot of Hoisington Walk

that featured fifty trainees lining the walk holding their state flags while

the garrison flag was lowered and the WAC Band played the national anthem. The

center historian wrote: "The 1200 members of the Women's Army Corps who

participated in this retreat ceremony realized that sharing the experience with

the present and former directors of their Corps made it a special and unusual

occasion." 27

On 18 July of that year, Fort McClellan celebrated its fiftieth anniversary,

and on 25 September, the WAC School marked its fifteenth year as an Army school.

Lt. Col. Maxene Baker Michl replaced

Colonel Branch in August 1968. Colonel Michl had served in Vietnam (1966-1967)

and most recently had been the WAC staff adviser to the Fourth Army (1967-1968).

When she arrived at WAC Center, the program to expand the WAC was in full acceleration.

The heavy input of trainees was overloading classrooms, instructors' schedules,

transportation facilities, and barracks. Closed-circuit TV was installed in

classrooms and barracks and soon helped reduce the instructors' platform time

and the cadre's night working hours. Colonel Michl also introduced a one-hour

evening study hall to ensure quiet time in the overcrowded barracks; group study

replaced it the following year when review lessons were shown on barracks televisions.

And, although the WAC had not experienced any drug problems, Colonel Michl added

a two-hour block on drug abuse to the basic training curriculum. Before the

end of 1968, she also introduced self paced instruction in the enlisted courses,

and by May 1969, this method had replaced the conventional instructor-taught

methods in the Clerical Typing and Procedures Course (MOS 71B) and the Stenography

Course (MOS 71C). It was also used in the Personnel Specialists Course (MOS

[342]

THE FIRST WAC CENTER

AND WAC SCHOOL COMMANDER/COMMANDANT to hold the rank of full colonel.

Col. Maxene B. Michl's silver eagles are pinned on by Maj. Gen. Joseph R.

Russ, Deputy Commander, Third Army, and Col. William A. McKean, Commander,

Fort McClellan, 4 December 1968.

71 H), which was added to the school's

schedule of courses in September 1969.28

With too many students, the school was obliged to make the students their own

instructors.

A surge of racial protests and disturbances

in U.S. cities in 1968 led Colonel Michl to introduce a series of lectures and

seminars on black studies in the officer courses. A black WAC officer, Lt. Col.

Williemae M. Oliver, Director of Instruction, developed and conducted the initial

program. Colonel Michl also established an ad hoc Committee on Race Relations

at WAC Center and WAC School in January 1970 and added a three-hour course in

race relations to the WAC basic training program in May.29

Several conspicuous individual firsts

also occurred at WAC Center during Colonel Michl's tour. On 30 March 1968, Sgt.

Maj. Yzetta L. Nelson, assigned to WAC Training Battalion, became the first

WAC

[343]

NEWLY PROMOTED COMD.

SGTS. MAJ. YZETTA L. NELSON AND CURTIS S. RAMSAY, Fort MClellan, 8 April

1968.

promoted to the new rank of command

sergeant major. On 31 July, the sergeant major of WAC Center, Elaine I. Slewitzke,

became the second WAC to achieve that rank. In a ceremony at the WAC Center

auditorium on 4 December 1968, Colonel Michl was promoted and became the first

WAC Center commander to hold the rank of colonel.30

The next year, in July, Colonel Michl formed the WAC Foundation, and, in September,

she obtained approval from the Department of the Army to publish the WAC Journal

to disseminate news and information of career interest to WAC officers and enlisted

women.31

In 1970, Col. Dorotha J. Garrison, who

had been deputy commander at the WAC Center for a year, succeeded Colonel Michl.

The influx of trainees continued, increasing each year during the Vietnam buildup.

The number of basic trainees jumped from 4,124 in 1967 to 7,139 in 1972. In

consequence, shortages of cadre, instructors, cooks, and housing plagued the

center. To alleviate these problems, Colonel Garrison and her staff initiated

a number of actions. Selected privates, first class, and corporals received

training to be assistant platoon sergeants; the battalion gave cadre and instructor

training to women newly assigned these duties; and, at the center commander's

request, the Department of the Army approved conversion of all the E-7 (sergeant,

first class) platoon sergeant

[344]

positions to E-7 drill sergeant positions

in that MOS. Thereafter, women ordered to fill these positions first attended

drill sergeants' school.32

Other changes included sending new recruits

directly to their basic training units during peak periods, rather than processing

them at Headquarters and Receiving Company. WAC Center's Headquarters and Headquarters

Company moved to a larger building on post (Building 3131) in January 1971 and

turned over its former quarters to the training battalion, which then, in February,

activated its sixth unit, Company F Provisional.33

To relieve the mess hall problems, KPs continued to report for duty in two (rather

than one) shifts (0400 to 1230 and 1030 to 1900); the battalion opened another

mess hall for trainees (Building 2203); and later, in 1972, after a study proved

it more economical, the Army hired cooks on contract to replace military cooks

at Fort McClellan.34

In anticipation of further WAC expansion, the post commander, Col. William A.

McKean, instructed Colonel Garrison to prepare a plan to accommodate thousands

more recruits beginning in 1972. Colonel Garrison proposed creating a second

and later a third basic training battalion and a reception station apart from

the battalion. CONARC and the Department of the Army approved both concepts

and later provided funds to construct or rehabilitate buildings to accommodate

them. WAC Center activated the 2d and 3d WAC Basic Training Battalions in September

1972.35

That year, CONARC ordered discontinuation of the WAC Officer Advanced Course,

the clerical training courses, and the NCO leadership courses.36

These changes further alleviated overcrowding, and, thereafter, women received

this training at other centers and schools.

At the peak of this activity, the last

WAC Officers Advanced Course class (XIX) graduated on 7 July 1972, with sixteen

WAC officers and seven foreign students (four from Vietnam, two from Indonesia,

and one from the Philippines). WAC officers thereafter attended advanced courses

at other branch schools. Speaking to the graduates, Maj. Gen. Ira A. Hunt, Jr.,

who had been deeply involved in the training aspects of the WAC expansion, outlined

the changes occurring in the Corps and explained the reasons for them:

[345]

COMD. SGT. MAJ. BETTY

J. BENSON, one of the first WAC graduates of the Sergeants Major Academy,

Fort Bliss, June 1973.

We have opened avenues to women across

the board to insure that they can get the training which will make them competitive

with men. Because no matter what you say, if the women don't have the training,

they can't get out and perform the job. So, in summary, . . . we can say that

the Army is breaking the barriers to full participation by women . . . that

discrimination is out; that institutional barriers are being removed; and having

done this, hopefully, ingrained inhibitions will be eroded.37

The last class (X) of the WAC NCO Leadership

Course graduated 41 students on 17 May 1972. Between 1968 and 1972, 380 women

had graduated from the course. Thereafter, enlisted women participated in the

Noncommissioned Officer Educational System that provided progressive training

at service schools and NCO academies at all skill levels. Both the Department

of the Army and the major commanders scheduled enlisted personnel for resident,

extension, and on-the-job training courses, ranging from primary technical courses

to the sergeants major course. The first WACs to graduate from the U.S. Army

Sergeants Major Academy at Fort Bliss, Texas, were Class I (June 1973), M. Sgt.

Betty J. Benson; Class III (June 1974), M. Sgts. Helen I. Johnston and Dorothy

J. Rechel. All later achieved the rank of command sergeant major, the highest

enlisted grade in the Army.38

[346]

On 23 August 1972, the remaining students

graduated from the WAC Clerical Typing and Procedures Course (MOS 71B), the

Stenography Course (MOS 71C), and the Personnel Specialists Course (MOS 71H).

In the future, WACs attended these MOS courses at other Army training centers

and schools to qualify in these skills. The Clerical Training Company was deactivated

on 5 October 1972.39

An eleven-week WAC Officer Orientation

Course (WOOC) for student officers and officer candidates replaced the WAC Officer

Basic Course/Officer Candidate Course (WOBC/OCC) on 1 January 1973. Upon completion

of the orientation course, the women attended an officers basic branch course

at another service school (Quartermaster, Military Police, Signal, etc.). The

average length of the courses was nine weeks. The last WOBC/OCC Class (XLII),

159 student officers and 7 officer candidates, graduated on 15 December 1972.40

Discontinuance of the courses at WAC

School provided office, barracks, and classroom space for the 2d WAC Basic Training

Battalion, which immediately occupied the vacated buildings. The 3d WAC Training

Battalion was activated in September 1972 in the area vacated by transfer of

the Chemical School training activities to other stations. A former officers

mess in the basic training area was opened to provide an additional facility

to feed up to 400 more trainees at a sitting. The WAC presence now occupied

more area of the post that it ever had before or would again.

While somewhat insulated from the racial

strife which confronted the country in the 1960s and early 1970s, WAC Center

and WAC School reflected society at large. On Saturday, 13 November 1971, those

institutions experienced racial conflict.41

Near midnight a group of black and white enlisted women (primarily clerical

training students at WAC School) and enlisted men from various units on post

left the Enlisted Men/Enlisted Women's Club (EM/EW Club) and prepared to board

Army buses to return to their barracks. As the group boarded a bus, the white

military driver allegedly said he would not take any blacks on the bus. The

blacks left and boarded the second bus, where they allegedly demanded that all

the whites get off. By this time, the first bus had left, and the whites would

have had no transportation. An altercation ensued. A military police car, standing

by to escort the club manager to the bank with his deposit, radioed for assistance.

[347]

Before assistance arrived, a group of

about sixty black men and women left the area on foot, shouting and chanting.

They marched through the main section of the post, damaged some cars along the

route, and generally impeded traffic. A car that pushed its way through the

crowd injured several marchers who had refused to move out of its way. An ambulance

removed the injured, and the crowd followed it to the post hospital about a

half-mile away. They left when hospital officials assured them that none of

their friends were seriously injured. The crowd then moved to the WAC School

area, another half-mile away. A number of the black women entered the women's

barracks, awakened the sleeping women, and encouraged them to join the group.

Many did. The group continued this process through the WAC area. Several MP

cars followed the group but did not impede its progress as it continued a noisy

march around the post. About 0400, the demonstrators tired and returned to their

barracks. The next afternoon, they met at the Hilltop Service Club near the

WAC area, discussed the night's events and their problems. They posted guards

who kept white men and women from entering the club. Late in the afternoon,

they moved en masse to the EM/EW Club and refused to leave it when ordered at

2130 hours, but they left voluntarily an hour and a half later.

The next morning, Monday, approximately

thirty black students at WAC School refused to report to their classes. Instead,

they walked to a baseball field near the center of the main post where they

joined many other black enlisted personnel. The group refused to disperse and

demanded that the post commander and unit commanders meet with them to discuss

a list of grievances. While this meeting was in progress, a white female reporter

from the local newspaper was assaulted by a group of black WACs because she

refused to stop taking notes during the meeting. At this point, the post commander

used 700 troops to apprehend and arrest approximately 139 demonstrators; 68

were black enlisted women. The Anniston city jail accommodated the women until

16 November when the military police moved them back to the post to a makeshift

confinement barracks guarded by WACs. The men were confined in the post stockade

and other jails in the area.

Within a month, the post commander and

WAC Center commander disposed of the charges. Of the 68 women confined, 2 were

promptly released because they had not been involved in the incident; 9 were

discharged; 46 were transferred from WAC Center or WAC School; and 11 remained

at WAC School to complete their clerical courses.

An investigation revealed that earlier

confrontations had preceded the demonstration. On Saturday, 7 November, about

100 black enlisted men and women had met with managers of the Hilltop Service

Club to ask why that club, predominately patronized by black service personnel,

did not hire black dance bands, had no soul music in the jukeboxes, and did

not have a black service club director. When the club employees could

[348]

not provide satisfactory answers, the

group asked for a conference with the post chaplain. When he arrived for the

scheduled meeting, however, they refused to talk to him because he was white.

They did, however, discuss their grievances with a male black major who accompanied

the chaplain at the request of the post commander, Col. William A. McKean. The

group discussed with the major the many inequities they suffered, particularly

regarding promotions and military justice, and they reported that their unit

commanders did not respond to their requests for information or assistance.

They asked for a meeting with the post commander. At that meeting, on the afternoon

of 13 November, Colonel McKean listened to their grievances and promised to

provide them with answers to their questions and resolve their problems at a

meeting scheduled for 16 November. The incident at the EM/EW Club occurred a

few hours later.

Immediately after the incident, Colonel

McKean ordered racial committees established in every unit, male and WAC, at

Fort McClellan. Each unit sent representatives to councils established at battalion,

school, and center levels where complaints could be aired, investigated, and

resolved. WAC Center had established such a council in 1970.

At the time of the incident, the WAC

School's Clerical Training Company (the unit home of most of the women demonstrators)

held 373 women of whom 20.8 percent were black. The barracks were full but not

overcrowded. Because training was conducted under the self-pace method, in which

each student progressed at her own rate, it was difficult to develop a unified

class spirit, the basis for good morale. (The inability to generate such feeling

was a frequent criticism of the self-pace method.) The company was supervised

by a commander, executive officer, first sergeant, supply sergeant, and five

platoon sergeants. The investigation report stated: "At least two weeks

prior to the incident almost complete racial polarization was effected among

the students in CTC, resulting in a complete breakdown of discipline and worsening

racial tensions. Black leaders undoubtedly contributed to the problem."

Although the unit commander and her staff knew the situation, the report continued,

they had taken no effective corrective action. During the demonstration, unit

officers and NCOs had failed to control the women, to establish dialogue with

the dissidents, or to show concern for their welfare. This lack of action had

worsened the situation. As a result of this report and her personal investigation

of the events, Colonel Garrison relieved the unit's commander, executive officer,

and first sergeant and replaced them.

The report concluded that throughout

the events preceding, during, and after the incident, the post commander and

WAC Center commander had acted with compassion, restraint, and concern and were

held blameless for the incident. The local newspapers and radio stations received

frequent, open, and detailed reports of the demonstration but had insisted upon

admittance of a reporter. The incident received meager national

[349]

publicity. The Third Army report summed

up the cause and solution to the incident:

From the onset of the Fort McClellan

experience, it became forcefully self evident that the good will, good intentions,

and total commitment of senior commanders to assuring equal treatment for personnel

are not enough to eliminate the racial problem. Many necessary actions were

indicated as a result of the racial disturbance but of all the lessons learned

or relearned, the need to improve communications upwards as well as down with

the young soldiers, and especially the young black soldiers, through the chain

of command, is most apparent." 42

On 1 October 1972, Colonel Garrison

retired and the director of the WAC selected Col. Mary E. Clarke, a former WAC

Training Battalion commander, to be the commander/commandant of the WAC Center

and WAC School. By this time, the WAC expansion campaign was well under way.

New arrivals during 1971 had averaged 360 recruits a month but rose during 1972

to 590 a month. The success of the new recruiting effort pleased Army planners,

but at WAC Center, where housing, classrooms, and personnel resources were strained

to the limit, it was a time of controlled panic. A parody composed and sung

by the training center cadre told the story.43

The WAC Center Lament

(To the tune of "On Top of

Old Smokey")

Down here at WAC Center, in August

last year

The general told us, "Expansion

is here."

She smiled and said, "Do it.

I do not care how.

It must be done quickly, so get

started now."

Headquarters is buzzing, with orders

and such.

DA gives direction but not very

much.

USAREC sends us trainees, they

come by the pack.

Last week we were busy, so we sent

them all back.

[350]

There's one NCO here for each thousand

troops.

Is it any wonder they all have

the "droops?"

For eighteen hours daily they toil

at their task.

Just how they can do it, I'd rather

not ask.

There are no replacements for those

of us here,

So we've all been extended for

at least ten more years.

So come all you women, come listen

to me.

It will be better in seventy-three.

We'll know what we're doing, we'll

get the job done.

Then we'll look back and laugh

and say "Wasn't it fun?"

[At the end, all responded with

a heartfelt and loud, "NO!"]

The huge influx of trainees forced the

new WAC Center commander to relocate more units and offices. WAC School, reduced

now to the College Junior Course and the WAC Officer Orientation Course, moved

its offices, classrooms, and student housing to buildings vacated by the Chemical

School. Meanwhile, the 2d WAC Basic Training Battalion, activated 17 September

1972, took over the WAC School (Faith Hall) for its headquarters and classrooms,

and the recruits moved into the quarters of the Clerical Training Company. The

battalion consisted of four companies, each with five platoons. Ten days later

the 3d WAC Basic Training Battalion opened with five companies, four platoons

each. It was located approximately one mile from WAC Center headquarters at

a site where the Chemical Training Command had conducted advanced individual

training and housed its students. Named "Tigerland," the area contained

old, one-story, wooden barracks that the women scrubbed, painted, and beautified

to the best of their ability with the help of male volunteers from the 548th

Service and Supply Battalion. Another major unit, Headquarters Battalion, was

activated in January 1973 in the WAC area. It supervised the Staff and Faculty

Company (permanent party instructors and administrative staff), the Special

Training Company that conducted remedial instruction for trainees, the Student

Officer Company that administered and out-processed women who failed to graduate

from one of the courses, and the 14th Army Band (WAC). Although the band moved

to a four-story building on post in September 1973, it remained under Headquarters

Battalion.44

As a result of a major reorganization

of the Department of the Army in 1973, several changes occurred in the relationships

between WAC Center, Fort McClellan, Third Army, CONARC, and the Department of

the Army. On 1 July 1973, the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC)

absorbed CONARC and the Combat Developments Command. A new command, the U.S.

Forces Command (FORSCOM) at

[351]

Fort McPherson, Georgia, absorbed the

missions of the Third U.S. Army and CONARC's readiness and reserve component

responsibilities. CONARC and Third Army were deactivated. Meanwhile, at Fort

McClellan a decision by the chief of staff to merge Chemical and Ordnance branches

caused discontinuance of the Chemical Center and School and dispersal of its

training and functions to other posts, primarily Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland.45

In the midst of the reorganizations

and WAC expansion efforts, the Defense Department threatened to close Fort McClellan

as part of a program to reduce the number of military installations commensurate

with the reduction in military forces. Initially, in April 1973, the chief of

staff announced that the Military Police activities at Fort Gordon, Georgia,

would move to Fort McClellan and that one WAC basic training battalion would

move to Fort Jackson, South Carolina. But, in July, a new study recommended

that Fort McClellan be closed; that MP activities remain at Fort Gordon; that

WAC basic training be dispersed to other training centers; and that the WAC

School be deactivated. The women's direct commission program would be discontinued

and WAC officer candidates would be trained with male officer candidates at

Fort Benning, Georgia.46

The threatened closure of Fort McClellan

generated complaints to Secretary of the Army Howard H. Callaway from the citizens

of Anniston and its congressional representatives, principally Congressman Bill

Nichols in whose district Fort McClellan was located. General Bailey and Colonel

Clarke fought to keep Fort McClellan open. General Bailey emphasized the WAC

identification with the post: "The women have been encouraged by seeing

that they are now receiving some priority in the Army policies and planning.

Their perception that the Army now wants to close their `home' facilities will

negate these favorable reactions."47

For her part, Colonel Clarke also opposed the closing: "It seems to me

that the middle of a WAC expansion is poor timing for the discontinuance of

the USWACCS [WAC Center and School]. Particularly do I feel this to be true

when I look back on the tremendous record of achievement made by this overtaxed,

understaffed organization in the turbulent year just passed." 48

After almost a year of indecision, Secre-

[352]

tary Callaway announced on 8 February

1974 that DOD had decided to retain Fort McClellan as an active post and to

relocate the Military Police training and school activities there in July. WAC

School continued to be slated for deactivation in 1976, ending separate training

for women officers.49

Despite the threat of closure, life

had gone on at Fort McClellan. The Army reorganizations brought changes that

had to be implemented. Between January and July 1973, WAC Center absorbed WAC

School; their staffs combined and a new organization emerged titled WAC Center

and School.50

On 1 July 1973, the new organization became a subordinate command of TRADOC

rather than of Third Army. Fort McClellan, however, continued to provide logistical

and other support services. Third Army established the much needed U.S. Army

Reception Station and attached it to the WAC Center on 30 January 1973 for command

and support services.51

The director of instruction for the newly formed WAC Center and School established

the Civilian Acquired Skills Program (CASP) in August to provide two weeks of

active duty training for reserve enlisted women in one of the basic training

companies.52

To get enlisted women into the replacement stream faster, TRADOC reduced the

length of women's basic training from eight to seven weeks beginning 2 July

1973 and focused training emphasis on learning "by doing" rather than

learning from lectures. That year WAC School initiated an instructor training

course and opened an Individual Learning Center in which trainees received remedial

instruction. In 1974, recruits began a sixteen hour basic rifle familiarization

course on the M16 rifle. Although firing the weapon was voluntary, trainees

attended and participated in the weapons training classes. Over 90 percent of

the women opted to fire. In the field training program, the day march increased

from one to two-and a-half miles; the night march from one to three miles. The

time devoted to physical training increased from twenty-five to thirty-five

hours. 53

WAC Center complied with expansion directives

to provide training for 7,000 basic trainees in FY 1973. But the original directives

and WAC Center's efforts were not enough; over 9,000 trainees arrived that year.

Shortages-housing, classrooms, trainers, and uniforms-again plagued the center.

Because the Army badly needed the additional WACs, the DCSPER, General Rogers,

had allowed the U.S. Army Recruiting Command (USAREC) to exceed its monthly

quotas. The overflow placed an

[353]

almost unbearable strain on the personnel

and facilities at WAC Center and School. Relocations provided additional housing

and classrooms in the WAC area, but problems mounted in maintaining high-quality

training and morale.

Higher headquarters placed a seemingly

unending stream of demands on the WAC Center and School staff for new and revised

plans, training programs, statistics, and reports. Colonel Clarke and her staff

developed a new expansion plan to accommodate 12,000 trainees annually. They

reorganized the WAC Center and School, revised or prepared new lesson plans

for enlisted and officer training courses, revised Role of the WAC for use in

male training courses, and provided countless statistical resumes and reports

to post, TRADOC, and ODWAC. When Colonel Clarke had an opportunity to ask TRADOC

to extend some of its short suspense dates and eliminate a few requirements,

she received some sympathy but no relief. The TRADOC commander replied, "As

you stated, considered singularly or as a group, your requirements are formidable

but I have no doubt that you will complete each task in an exemplary manner."54

As the expansion progressed, a drastic

shortage of uniforms developed. In particularly short supply was the three-piece

exercise suit worn by the trainees, but other uniform items were also affected.

Many women left the center without a complete issue of uniforms, dispersing

the problem to posts throughout the continental United States. The shortages

continued because the Recruiting Command exceeded its WAC enlistment objectives

in FY 1973, 1974, and 1975, and the DCSPER could not provide the Army Clothing

Depot at Philadelphia with adequate lead time to manufacture the thousands of

uniforms needed. And, as all these expansion-related problems were being resolved,

the effort at WAC Center and School attracted high-ranking visitors. They wanted

to see, firsthand, the results of the highly successful WAC recruiting and training

program. 55

By the fall of 1973, Colonel Clarke

had made progress in managing the heavy trainee input and the administrative

burdens by gradually realigning the organizational structure and by relocating

units. Hope for a respite, however, vanished in October 1973 when the chief

of staff approved a plan to double WAC enlisted strength by the end of FY 1979.

Because WAC Center had reached its capacity, General William E. DePuy, the TRADOC

commander, directed Maj. Gen. Robert C. Hixon, the commander of the U.S. Army

School/Training Center, Fort Jackson, South Carolina, to establish a WAC training

brigade with two battalions to train approximately 8,000 WAC recruits annually.

The post also received the mission of providing seven weeks of basic training

for approxi-

[354]

mately 3,000 reserve women recruits.

When basic training began at Fort Jackson, the 3d Basic Training Battalion at

WAC Center would be deactivated. TRADOC also began planning to conduct additional

basic training for WAC recruits at other Army training centers-Fort Leonard

Wood, Missouri, and Fort Dix, New Jersey.56

WAC training was quickly organized at

Fort Jackson. On 1 October 1973, the 17th Basic Training Battalion (WAC) was

activated with nine basic training companies and a Special Training Company

(remedial training). In honor of the occasion, General DePuy attended the command's

activation, unfurled the battalion's colors, and presented them to the commander

of the new battalion, Lt. Col. Joanalys A. Bizzelle. Training began 9 January

1974. The 5th Basic Training Brigade and the 18th Basic Training Battalion (WAC)

were activated on 1 July 1974. The 18th, commanded by Lt. Col. Doris L. Caldwell,

took four companies from its sister battalion and began training immediately.

The brigade provided command and control over the battalions. Its first commander

was Col. Edith M. Hinton. Fort Jackson conducted the women's basic training

course for three years. Then, in 1977, TRADOC combined basic training for men

and women and deactivated the women's brigades and battalions at Fort McClellan

and Fort Jackson .57

During the two years that Colonel Clarke

commanded WAC Center and School, its look and pace had changed significantly.

By the end of September 1974, she commanded a center with four battalions rather

than one, a school with two courses (WCOC and College Juniors) rather than seven,

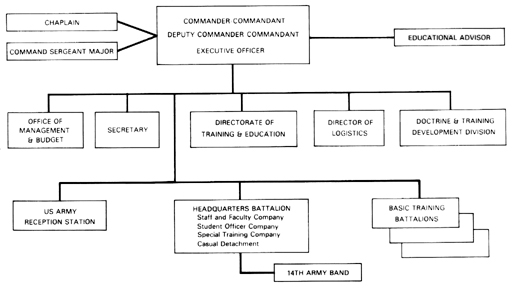

and an Army reception station. (See Chart 5. ) Command and operational control

of the 14th Army Band (WAC) had passed to the commander of the Special Troop

Command, Fort McClellan, on 1 May 1974. The commanders of the 1st and 2d Basic

Training Battalions had moved into new headquarters office buildings in February

1974, and the 3d Basic Training Battalion prepared for deactivation in December.

Construction was under way in the WAC area to enlarge the clothing issue warehouse,

the dispensary, and the post exchange and to build a small headquarters for

Headquarters Battalion. The post engineer was also renovating mess halls, barracks,

and classroom buildings so the WAC Center could accommodate twice as many recruits.

In September 1974, when Colonel Clarke prepared to leave Fort McClellan, she

wondered about the future of the WAC Center and School. Indications were still

that it would close and basic training would be reduced to two battalions. Her

fears were well founded. In November, the TRADOC commander

[355]

CHART 5- WAC CENTER AND SCHOOL, FORT McCLELLAN ORGANIZATION, 1974

Source: Historical Report, WAC C&S,

1974, p. ii.

ordered Fort McClellan to reorganize

and place all its activities under one command, eliminating WAC Center and School,

the Military Police School, and the U.S. Army School/ Training Center (USASTC).58

In 1975, the Army ended the 32-year

tradition of an all-female band in the Army and the unique career of the 14th

Army Band (WAC). Although other services had women's bands from time to time,

none had a long or continuous history. The 14th Army Band (WAC), activated on

16 August 1948, received title to the lineage and honors of the 400th Army Service

Forces Band (WAC) that had begun its career in 1943 as one of the five WAC bands

organized during World War II. After activation, the 14th Army Band (WAC) trained

for six months at Fort George G. Meade for its role as the WAC training center

band. On 5 March 1949, the band's first ten members and its warrant officer

bandmaster, Miss Katherine V. Allen, were welcomed to Camp Lee by the WAC training

center command. In the next three months, sixteen more bandswomen

[356]

DANCE BAND OF THE 14TH ARMY BAND (WAC),

WAC Center, Fort MCClellan, 1965.

joined the unit, and the band began

its routine of playing for parades, march-outs, orientations, graduations, receptions,

conferences, and dances. It also gave concerts on post, in the local community,

and at nearby Veterans Administration hospitals. When the unit acquired its

full complement of thirty-four women, Miss Allen, a graduate of the Juilliard

School of Music, formed a number of small internal groups-a dance band, a Dixieland

jazz combo, a barbershop quartet, and others-to provide a variety of musical

entertainment.59

[357]

THE 14TH ARMY BAND (WAC) in parade

formation, 1970.

In 1951, the 14th Army Band (WAC) began

touring. To assist the campaign to build WAC strength during the Korean War,

the band toured the First, Second, Fifth, and Sixth Army Areas in 1951; the

Third Army Area in 1952; and previously unvisited states in the Fifth Army Area

in 1953. After moving to Fort McClellan with the WAC Center in 1954, the band

continued to make special trips and conduct concert tours with community activity

program funds provided by the Army's Information Office, CONARC, Third Army,

or Fort McClellan. Its special trips ranged from appearances at the World's

Fair in New York in 1956 to marching in three presidential inaugural parades

(1953, 1957, and 1961). After the 269th Army Band at Fort McClellan was deactivated

in September 1960, the WAC band functioned as the post band, provided buglers

for military funerals in Alabama and Mississippi, performed its duties at WAC

Center, and continued to make tours. Tours between 1951 and 1973 took the band

through almost every state in the Union and, in November 1972, to Puerto Rico,

where it spent a week on a recruiting concert tour. On its travels, the band

played at high schools, colleges, civic centers, and for community events (festivals,

fairs, races, football games, parades). Personnel at Fort McClellan greatly

missed the band while it was on these trips; they had to endure recorded music

at parades and other ceremonies. Recruiters meanwhile welcomed the band into

[358]

their areas where its appearances increased

public awareness of the Corps and boosted WAC recruiting.

The bandmaster commanded the women and

was their musical instructor and director until 1964. After Miss Allen completed

her tour in 1952, she was replaced by 2d Lt. (later Captain) Alice V. Peters,

who remained in this position until 1961. A series of officers served in the

position thereafter, usually for a two-year tour. In 1964, after difficulty

finding a fully qualified warrant or commissioned woman officer, the grade and

nature of the position changed. The job of commander/bandmaster was upgraded

to captain, and an enlisted bandleader (E-7) was added to direct the band and

provide instruction and technical guidance. To fill this key bandleader position,

the center commander selected Sp6c. Ramona J. Meltz, an accomplished musician,

director, and instructor, and a nine-year veteran of the band. A natural leader,

Specialist Meltz quickly gained the respect and support of the other members

of the band. During the ten-year period she held the position, she continuously

sought promotions, awards, improved housing, and better equipment for the women.

At the same time, she was their severest critic and taskmaster in musicianship

and attention to duty. Her leadership developed an esprit de corps among the

members of the band that was unparalleled among WAC units. Because organizational

bands had no cadre positions authorized, the commanders usually assigned the

additional duty of first sergeant to the women who served consecutively as drum

major for the band between 1950 and 1973-M. Sgt. Janet Helker, Sgt. Eva J. Sever,

Sgt. 1st Cl. Jane M. Kilgore, Sgt. 1st Cl. Rosella Collins, and Sgt. 1st Cl.

Margaret R. Clemenson. In 1966, a bass horn musician with administrative skills,

Sgt. 1st Cl. Patricia R. Browning, accepted the additional duty of first sergeant

and held it until she transferred to another band in 1974.

Initially, the band was housed in a

combined barracks and rehearsal hall in the basic training area at Fort McClellan.

In 1967, when the WAC expansion for Vietnam began and the battalion needed more

room for recruits, the band moved into a building vacated by Headquarters and

Headquarters Company (WAC). This building was small, but the band remained there

until September 1973. It moved to a four-level building in the main post area

where, for the first time, it had adequate space for a rehearsal hall, library,

practice rooms, instrument repair room, administrative and supply offices, and

comfortable living quarters for the bandswomen.

Over the years, the band increased its

stature and prominence. In 1966, more women began to attend the bandsman's course

at the U.S. Naval School of Music. Up to then, only five women had attended,

primarily because the attendees' services were lost to the band for twenty-three

weeks. This situation was alleviated in 1968 when the band increased in size

from forty-three to sixty members. In the 1960s, the band appeared on national

television, in the movies, and in Army training and informa-

[359]

tion films. The band played at the White

House in 1967, when President Johnson signed the bill (PL 90-130) that removed

promotion restrictions on women officers and in the Rose Bowl Parade in January

1969. It also made a number of records and in 1973 won Best Military Band award

for the fifth consecutive year at the Veterans' Day Parade in Birmingham, Alabama.

Through the years, the band expanded its versatility by adding more special

groups-swing band, choral group, rock combo, country and western groups, and

a chamber music quartet.

At WAC Center, the band was an integral

part of life for recruits, students, and permanent party personnel. It was a

part of every official and unofficial ceremony that took place, and it boosted

morale by voluntarily initiating events like marching from unit to unit during

the Christmas season singing and playing carols, giving a spring and fall concert

for the trainees, and serenading various officers and NCOs on their birthdays.

Band members had a special place in the hearts and lives of the WACs at Fort

McClellan, and, for their part, band members developed such unit esprit that

few requested transfer. Women who auditioned for the band knew from the beginning

that they would serve continuously in the band unless they requested reenlistment

and training in another MOS. Most elected to remain with the 14th Army Band

(WAC) throughout their service.

The band was at the peak of its development

when, despite efforts to avert the change, the Army ordered the unit to be integrated

with male personnel. In July 1972, the WAC Center commander, Colonel Garrison,

moved to preserve its all-female status by requesting that it be designated

a Special Band. The intervening commands and the director of the WAC concurred,

but the Army staff disapproved because it could not spare the eighty-three additional

spaces required.60

The next year, an Army-wide reduction in force required the band to trim its

strength from sixty-four to an authorized twenty-eight members. The losses devastated

morale. Members went to other bands in CONUS and overseas; some retired. In

1974, several male bandsmen requested assignment to the band at Fort McClellan,

but the 14th Army Band (WAC) did not accept men. In 1975, the adjutant general

advised the Department of the Army's General Officer Steering Committee for

Equal Opportunity that "maintenance of the 14th Army Band (WAC) as a female-only

unit appears to be in conflict with EEO [Equal Employment Opportunity] policies

relating to discrimination based on sex."61

When asked to comment on integrating the band, the

[360]

Army's chief information officer had

no objection. The commander of TRADOC felt it should take place as a matter

of equity. The commander at Fort McClellan agreed in principle, but reminded

TAG that the band annually drew great public acclaim through hundreds of appearances.

It gave visibility to women serving in the Army, and its effectiveness in WAC

recruitment, especially during the current expansion, was unparalleled. If integrated,

the commander pointed out that "the 14th Army Band would become just another

installation band ... its uniqueness would cease."62

The WAC director agreed with those comments and recommended that integration

at least be delayed until 1977 to ensure "the least adverse impact on morale."63

The steering committee, therefore, directed that the band be fully integrated

by 1 January 1977, the day after the training brigade at Fort McClellan would

assume most of the functions of the WAC Center and School. After that edict,

integration of the band began, and the acronym WAC in parentheses was removed

from the band's title effective 1 July 1976.64

Other changes also occurred. Master

Sergeant Meltz, although she had been selected for promotion to sergeant major

(E-9) in 1973 after the position was raised to that grade, decided to retire.

She received the Legion of Merit for her performance of duty between January

1962 and November 1973. Lt. Paula M. Molnar became the last woman officer to

serve a full tour of duty as commander/bandmaster (1973-1975). After some temporary

commanders, a male warrant officer was assigned as bandmaster in September 1976,

and, thereafter, the band had male bandmasters and enlisted bandleaders.65

Beginning in 1971, the U.S. Army Field

Band included WAC vocalists in its tours, and in 1973, the first WAC was assigned

to the U.S. Army Band at Fort Myer, Virginia.66

Thereafter women served interchangeably in these special bands, the U.S. Army

Chorus, and in bands at other installations and activities. Deactivation of

the 14th Army Band (WAC) closed a chapter in the history of the Women's Army

Corps and left Corps members with fond memories of marching behind the band

at parades, Arbor Day plantings, Christmas caroling, torchlight processions,

concerts, orientations, and graduations at the WAC Center and School. The pride

of the WACs, the 14th Army Band (WAC), had had a long

[361]

and illustrious career as an all-female

band. And while its integration was both inevitable and unwelcome, the band

did survive the change.

When Col. Mary E. Clarke completed her

tour as commander of WAC Center, she exchanged positions with Col. Shirley R.

Heinze, who headed the WAC Advisory Branch (formerly WAC Career Management Branch)

in Alexandria, Virginia. The change of command ceremony was held on 4 September

1974 at Fort McClellan. Colonel Heinze was the first graduate of the Army War

College (Class of 1968) to command the center. Like Colonel Michl, she had completed

a tour of duty in Vietnam (1966-1967).

Because the expansion caused many women

to move into nontraditional jobs that required knowledge of defensive tactics

and weapons, these subjects became mandatory in WAC basic training. Even cooks

and bandsmen assigned to certain units and locations had the secondary mission

of helping their unit perform rear area security (guarding against enemy attack

or infiltration). On 25 March 1975, upon the recommendation of the DCSPER and

TRADOC, Secretary Callaway announced that this training would be mandatory for

women enlisting or reenlisting after 30 June 1975. At TRADOC's direction, Colonel

Heinze and her staff revised the basic training program and officer training

course to include weapons qualification and defensive techniques, such as digging

foxholes. Male trainees and student officers had to qualify on the M16 rifle

before they could graduate from basic training. Beginning in December 1976,

women had to do the same. During field exercises, an individual's entire unit

had to qualify on its basic weapons to pass readiness inspection.67

Earlier that year, at TRADOC's direction,

Colonel Heinze had expanded the weapons training program to include additional

small arms weapons. Up to this point, women had trained on the M16 rifle. In

July 1976, TRADOC added training on the light antitank weapon (LAW), the 40-mm.

grenade launcher, the Claymore mine, and the M60 machine gun. Women began training

on the hand grenade in the spring of 1977 after a test conducted at Fort Jackson

determined that women had the shoulder and arm strength to throw a hand grenade

accurately.68

To develop the

[362]

women's strength and stamina, physical

training was expanded to include more exercise, and the day march was lengthened

from two-and-a-half to six-and-a-half miles. Also, at a surprise point along

this march, the unit would receive a light dose of smoke that simulated tear

gas and required the women to put on their gas masks quickly and disperse in

the woods to hide. In 1976, helicopter familiarization added interest to the

field training course. With the increased emphasis on physical training, field

training, defensive techniques, and weapons training, the women's training duty

uniform at WAC Center changed from the familiar three-piece exercise suit to

the heavy-duty fatigues, helmet liners, and combat boots worn by men in basic

training.69

In September 1975, Army Chief of Staff

Frederick C. Weyand visited WAC Center and School to observe women's training.

Maj. Gen. Joseph R. Kingston, commander of all training activities at Fort McClellan,

suggested a consolidated basic training course for men and women. A trained

infantry officer, General Kingston had seen how quickly the women had adapted

to changes in their training program, had become proficient in weapons training,

and had increased their physical capabilities. He had seen their confidence