- Chapter XIII

- Women in the Army

- When General Clarke became director of the Women's Army Corps on 1 August 1975, the question concerning dissolution of the Corps was no longer if, it was when. In June, during hearings on the proposed Defense Officer Personnel Management Act (DOPMA), the Army had told Congress that it would no longer insist upon retention of a separate Corps and director. It would, however, need a "full-time senior female officer to act as advisor . . . and spokesman for women in the Army."1 When the Defense Department revised the bill after those hearings, it eliminated the WAC as a separate corps and the position of director of the WAC. The bill already deleted the separate WAC promotion list. It did not contain a provision for the senior woman adviser deemed necessary by the Army, but it did contain other highly controversial provisions which generally ensured that DOPMA would not be approved by Congress for several years.

- Mary Elizabeth Clarke entered the Army at age 20 and, in August 1945, attended the last World War II WAC basic training class at Fort Des Moines. In September 1949, she graduated from WAC OCS at Camp Lee. Her assignments into the 1960s included detachment commander, WAC recruiting, and staff positions in personnel and intelligence. After spending a year at the Office of Economic Opportunity, Washington, D.C. (1966), and two years as commander of the WAC Training Battalion (1967-1968), she was assigned to ODCSPER for three years (19681971). She then served as the WAC staff adviser at HQ, Sixth Army, until September 1972 when she assumed command of the WAC Center and WAC School. She was chief of the WAC Advisory Branch at the time of her selection as director of the WAC. In seniority, she was the third-ranking eligible officer, and, like her predecessors, she was selected to head the Corps based on her demonstrated leadership, executive ability, and public relations skills.2

- [367]

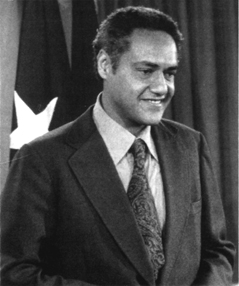

- COL. EDITH M. HINTON, DEPUTY DIRECTOR, WAC (1975-1978).

- On 1 August 1975, Acting Secretary of the Army Norman R. Augustine and Vice Chief of Staff Walter T. Kerwin, Jr., pinned general's stars on the ninth director while members of her family, friends, former directors, and members of the Army staff looked on. Adjutant General Verne R. Bowers administered the oath of office.3 That evening at the Fort McNair Officers Club, the chief of staff hosted a formal reception honoring the outgoing and incoming directors.

- General Clarke's staff was a mixture of new and old members. Well before her selection, two members had submitted their papers to retire on 31 August-Col. Maida E. Lambeth, the deputy director, and Lt. Col. Elizabeth A. Berry, the executive officer. General Clarke selected Col. Edith M. Hinton to be her deputy. A graduate of Army War College (1972), Colonel Hinton had been training director at WAC Center and School (1973-1975) and commander of the 5th Basic Training Brigade (WAC) at Fort Jackson (1974-1975). Lt. Col. Patricia A. McCord replaced Colonel Berry. 4

- [368]

- No stranger to the need for adequate planning, General Clarke had assumed command of the WAC Center and WAC School as the WAC expansion effort had begun. There she had seen the results of an oversupply of recruits and an undersupply of troop housing, cadre, instructors, uniforms, and classrooms. Now, as director of the WAC, with responsibilities as a top planner, she would spend a major proportion of her time working on the continued expansion and on studies dealing with the expansion's impact on the Army.

- During the first years of the expansion, the WAC Expansion Steering Committee's overriding concern had been recruiting. The committee directed the opening of more MOSS, enlistment options, and training courses to increase the attractiveness of enlistment and reenlistment in the WAC. They overcame shortages in uniforms, housing, and cadre by taking special actions-awarding bonuses to manufacturers to produce women's uniform items, sending teams Army-wide to find potential cadre members and to inspect housing. Policies that in the past had impeded utilization or assignment of women had been banished. The result, a steadily increasing number of WACs, convinced the committee that expansion was their best hope of eliminating the manpower shortage in the Army.

- In late 1974, Assistant Secretary of the Army (M&RA) M. David Lowe turned the committee's attention to the consideration of new concerns. He asked them to think about the effect that a higher percentage of women would have on the Army and on its ability to fight. He told the DCSPER, "We do not have a clear answer to the question, `how many women do we want in the Army-unit by unit, MOS by MOS?' . . . until we can nail this down, we may be setting objectives that are meaningless."5 The assistant secretary's representative on the committee, Clayton N. Gompf, warned members of the consequences of unrestricted WAC enlistments and assignments, saying, "A Category II unit, such as an MP company, could end up with 80 percent women."6 The implication, which no one disputed, was that this would render the unit unfit to accomplish its mission.

- After deliberation on the question, the members of the committee presented two recommendations upon which the DCSPER acted. First, he directed the commander of the Military Personnel Center (MILPERCEN) to develop a computer model to answer the question, "How many enlisted women do we need, MOS by MOS?" Second, he asked the commander of the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) to ana-

- [369]

- lyze the Army's manpower requirements to answer the question, "How many enlisted women can a unit hold without degrading its ability to perform its mission?"7

- To execute its task, MILPERCEN designed two computer models. The first, the Women's Enlisted Expansion Model (WEEM), was completed in October 1975. It determined women's MOS requirements by subtracting from total Army enlisted requirements all combat authorizations and developed a ratio of spaces for male promotion, rotation, grade distribution, length of overseas tour, and career development. This process revealed that up to 8 percent (54,400) of the Army's enlisted MOS spaces could be filled by women.8 The second model, the Women Officers Strength Model (WOSM), was patterned on WEEM and based in part on a

- TRADOC study. It showed that approximately 16 percent (26,400) of the officer spaces (including medical department officers) could be filled by women.9

- TRADOC completed its report, WAC Content in Units, in April 1975. This work established the percentage of women that could be assigned to TOE units (combat support and combat service support). The percentage, ranging from zero to 50 percent, was based on how close to the battlefield a unit normally operated. For example, a unit that would not leave the United States in time of war could have women filling 50 percent of its spaces; a unit that would operate within the combat zone could have no women at all. As distance from the battlefield increased, so did the percentage of women a unit could have. The system applied only to conventional war situations in which zones could be established. (In a nuclear war, it was assumed, whole continents would become the battlefield.) In forwarding the report, the TRADOC commander, General William E. DePuy, acknowledged its limitations: "There is no perfect way to arrive at a maximum ceiling on the number of women who can be assigned to TOE units .... The determination of specific percentages to express ceiling limitations is largely a subjective exercise."10

- The DCSPER, Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore, sent the TRADOC report to major commanders. He asked them to evaluate the recommended percentages against actual units of the same type then operating in the field. The commanders reported that the TRADOC-recommended percentages of women for TOE units appeared acceptable. They also indicated that women could occupy the majority if not all spaces in TD units. Several commanders, however, noted that in dealing with TOE units,

- [370]

- their comments should be considered conjecture because they had had little experience with sizable numbers of women in these units.11

- With this qualified acceptance of the TRADOC study, General Moore tried another tack. He asked MILPERCEN to use the TRADOC formula in the computer model WEEM to determine the requirements for enlisted women by MOS and by unit.12 The resulting figure, 91,000 enlisted women, was higher than the DCSPER anticipated or liked. He already believed that the DOD-directed expansion goal of 50,400 was too high and that a further expansion goal based on the new figure would outstrip the Army's ability to perform its mission. He had some support from General Clarke, who had kept close track of the reports, their review, and the comments returned by the commanders. She did not favor expanding WAC numbers to any extent that would require lowering WAC enlistment standards. When the DCSPER sent the estimate to Assistant Secretary Lowe's successor as ASA (M&RA), Donald G. Brotzman, he recommended that the results of the WEEM not be released to the news media. Time was needed, he wrote, to conduct a field test of the TRADOC formula. The results were not made public.13

- The task of field testing the TRADOC formula went to the Army Research Institute (ARI) and the U.S. Army Forces Command (FORSCOM). ARI spent a year designing and preparing the test entitled Women Content in Units Force Development Test and known as MAX WAC. In October 1976, forty combat service and combat service support units (Medical, Military Police, Maintenance, Signal, and Transportation) at nineteen posts in the continental United States and Hawaii participated in the first part of the test. During a three-day field exercise, ARI and FORSCOM representatives conducted interviews and tests to evaluate how well each unit, with a female content ranging from 10 to 35 percent, performed its mission. Six month later, the three-day field exercise and tests were repeated in the same units using a different percentage of women in the units.

- In January 1977, the preliminary findings indicated that a content of up to 35 percent women had no adverse effect on a unit's ability to perform its mission. Leadership, training, and morale were the factors that influenced results. The commander of the U.S. Army Operational Test and Evaluation Agency (OTEA), Maj. Gen. Julius W. Becton, Jr., however, had disputed those initial results. He thought that the methodol-

- [371]

- ogy was faulty and that the data did not support the findings.14 When the second test confirmed the initial findings, the chief of staff directed General Becton to analyze the methodology, design, and findings of MAX WAC. General Becton's study showed that the units could only support an upper limit content of 20 percent women, and he recommended that women's performance be tested in a two-or three-month field exercise under more realistic conditions.15

- The DCSPER, then Lt. Gen. DeWitt C. Smith, Jr., published the final results of the MAX WAC test in October 1977 and included OTEA's analysis as an appendix. In his foreword to the report, the DCSPER gave MAX WAC faint praise and noted that a further study would be conducted under prolonged field conditions. "The MAX WAC study was extremely useful and provides some insight to the U.S. Army in evaluating the role of women. The MAX WAC test in itself does not provide an empirical basis to objectively establish an upper bound on the potential number of women in support roles."16

- General Smith had also authorized ARI to test the TRADOC formula during the Army's annual REFORGER (Repositioning of Forces in Germany) exercise between July and October.17 Two hundred and twenty-nine women accompanied the REFORGER 77 troops to Europe where ARI observer teams closely evaluated the women's performance in their MOSS and their ability to adapt to field conditions. They were assigned to Signal, Transportation, Medical, Maintenance, and Military Police units. No unit had a female content higher than 10 percent. On 9 November, ARI reported its findings to the DCSPER and the Army staff. The team found that the addition of women had no adverse impact on unit missions. The women were proficient in their MOS duties and generally performed them as well as or better than men. The women, however, did not perform as well as men in the use of weapons or tactics, nor did they exhibit a desire to learn to fight. Some women had minor problems adapting to sanitation and billeting in the field, and, throughout the exercise, some men had difficulty accepting women's participation in the exercise.18

- [372]

- With the REFORGER report, REF WAC 77, the DCSPER now had three studies. Each recommended a different optimum percentage of women in units-35 percent, MAX WAC study; 20 percent, OTEA review; and 10 percent, REF WAC 77. While the next step could have been a study on the three studies, the DCSPER generally accepted the TRADOC's 35 percent maximum as a guide because both the MAX WAC and the REF WAC 77 studies had confirmed its basic premises.

- While the MAX WAC study was in progress (1975-1978), successive assistant secretaries of defense (M&RA)-William K. Brehm, John F. Ahearne, David P. Taylor, and John P. White-continued to press the Army to meet its numerical objectives and fill the manpower gap. At the end of December 1975, the Army was understrength by 16,200 enlisted men. Meanwhile, WAC numbers surpassed their FY 1975 goal by 5,800 women, and, by the end of the next fiscal year, the Corps exceeded its higher programmed strength by 3,000 enlisted women.19 It was not hard for General Moore, then the DCSPER, to guess that the continuing success of the WAC expansion would lead the Department of Defense to direct another big increase in women. He, however, was convinced that a higher density of enlisted women would undermine Army readiness, even though no study had proven this-the WEEM, TRADOC, and MAX WAC studies supported up to 35 percent in TOE units and almost 50 percent in TD units. On 6 January 1976, to prepare for another Defense Department request to increase WAC strength, General Moore directed his staff to "revalidate the program for the expanded utilization of women in the Army."20

- The study was published in December 1976 and was known as the Women in the Army (WITA) Study. It examined the expansion, women's policies and procedures, and research on women. The study group reviewed old opinion surveys and also sent major commanders a questionnaire on personnel policies that affected utilization of women. In their responses, the commanders reported that to date neither pregnancy nor single-parent policies had presented problems. They recommended that women be permitted as close to the battle zone as necessary to perform their noncombat duties. They also felt women needed additional physical, weapons, and tactical training. Some thought that women could fill MOSS in some of the Category I (combat) units-units that did not enter the battle zone. Only physical strength, in their opinion, appeared to be a differentiating factor between the performance of men and women. They

- [373]

- also agreed that men accepted women in leadership roles when they demonstrated supervisory and physical competence.21

- As part of the WITA studies, the Army Center of Military History (CMH) reviewed historical instances of women in combat and in combat leadership roles. Its report covered conventional as well as guerrilla wars and nine foreign countries, among them Russia, France, Italy, Great Britain, Israel, and Vietnam. Each of the countries chosen for the study had experienced times when women had entered combat to help their country repel attack or resist occupation by a foreign power. Russian and Israeli accounts showed that women had been successful leaders as tank commanders and infantry platoon leaders, but such instances were rare and no stories of unsuccessful female leadership could be found. In Israel, after the 1948 War of Independence, legislation had established a separate women's corps and also banned women from combat tasks on the battlefield. The legislation was based on statistics that showed higher casualty rates in mixed as opposed to all-male units. The CMH study concluded that insufficient evidence existed to determine whether women would be successful in combat or as combat leaders.22

- Completing its work in August 1976, the WITA study group found that the two computer models, WEEM and WOSM, provided "sound approaches" to establishing recruiting objectives, training, and MOS requirements for women. However, the issues of pregnancy and single parenting needed more data before any changes in policy could be considered, and additional research was needed to evaluate the physiological, psychological, and sociological factors affecting women in nontraditional roles and their reaction to combat stress. The group recommended that six of the MOSS involving combat support then open to women be closed to women and that thirteen others be temporarily closed until rotation and some long-range career programming problems could be resolved. The WITA report concluded that "while there is considerable work left to do, the Army is on the right track. The current [WAC expansion] plan for women is acceptable and will not lead to an organization which will be ineffective in time of war." In December 1976, General Moore distributed the 322-page report throughout the Defense Department, the Army, the other services, and interested former military personnel. He disbanded the WAC Expansion Steering Committee and, on 1 January 1977, replaced it with the WITA Review Committee.23

- [374]

- In November 1976, the WITA study helped General Moore convince Secretary of the Army Martin R. Hoffmann that the women's strength objective should remain at 50,400 enlisted women and 2,841 women line officers. However, incoming President James E. Carter brought in a new secretary of defense, Harold Brown, who ordered his assistant secretary for manpower and reserve affairs to determine where military personnel economies could be effected. Because past studies had shown that women cost less to sustain than men, the assistant secretary asked the services to study their utilization policies and to state whether they could double the strength of their women's components by the end of FY 1982.24

- Such an increase meant a WAC enlisted strength of approximately 100,000; women line and medical officer strength, 10,000. But the Army, reviewing its women's utilization policies and strength, decided that it had gone as far as it could on both counts. Noting that it had accomplished a fourfold increase in the number of women since 1972, the Army wanted time to evaluate the impact of that increase before initiating another major jump. Its ongoing research projects and field tests, to be completed in the next two years, would provide the data to guide further decisions on increasing enlisted women strength beyond the programmed 50,400 by the end of FY 1979. The Army, however, felt it could increase the total women officers program from 4,800 to 9,000 by the end of FY 1982.

- General Clarke did not concur in the reply that the DCSPER proposed to send to DOD. She now believed that the recruitment of enlisted women could sustain its momentum without lowering enlistment standards and that the Army's failure to increase its annual WAC accession targets and the five-year end strength would be a disaster. In fact, failure to increase accessions would result in WAC strength's being lower than 50,400 by the end of FY 1982. She wrote: "This has not been an effort to see if we could use 100,000 women; the effort has been to prove that we could not."25 General Moore noted General Clarke's nonconcurrence but overruled it, stating that to agree to any increase in the enlisted women's strength would compromise the strong position he wished to take on the assistant secretary's proposal. Though his own statistics and studies proved otherwise, the DCSPER believed a higher content of women would dilute the Army's ability to perform its missions. He told

- [375]

- the assistant secretary, "We should err on the side of national security until such time as we have confidence that the basic mission of the Army can be accomplished with significantly more female content in the active force."26

- Among the services, only the Marine Corps submitted a plan to double the size of its women's component by the end of fiscal year 1982. (See Table 29. ) However, the data presented by the Navy and Air Force convinced Secretary Brown that problems in managing rotation meant that the number of women in those services could not be doubled until Congress removed restrictions on women serving on ships and planes. The Army did not fare as well.

- [In Thousands]

- Source: DOD Rpt, Background Study, Else of Women in the Military, May 77, pp. 32, 40, 42, ODWAC Ref File, Studies, CMH.

- In evaluating the Army's plan, the assistant secretary of defense (M&RA) told Secretary Brown that he felt the Army could have programmed a gradual increase in enlisted women. To him, it appeared that the Army was "over-controlling" enlisted women's accessions and manpower positions through the Women's Enlisted Expansion Model (WEEM) and that relatively small adjustments in the WEEM ratios for promotion, rotation, and other factors could significantly increase projections for increased utilization of enlisted women. The WITA Study, enclosed in the Army's response, documented that women lost less time from duty than men for all causes except pregnancy and that women had higher retention rates than men. Preliminary reports from the MAX WAC study indicated that unit performance was not affected with up to 35 percent women. "It appears," the assistant secretary wrote, "the Army can use more enlisted women. They will help make the all-volunteer force succeed and will save money." Then he added, "but the growth

- [376]

- must be watched to ensure that the fighting capability of the Army is strengthened, not weakened by additional enlisted women."27

- At the time of the study, women constituted 5 percent of the total armed forces. Costs of recruiting female high school graduates were lower than those for recruiting male high school graduates. Women had higher overall retention rates than men, in addition to lower loss rates in their first year of enlistment. Even though involuntary discharge on pregnancy and parenthood had been eliminated by DOD two years earlier in 1975, pregnancy remained a major cause for discharge of women from military service. But studies showed that men lost more time from duty than women, considering all causes. Major causes of lost time for men included alcohol and drug abuse, AWOL, and desertion. Disciplinary problems among women were rare.28 "The average female recruit was about a year older than her male counterpart . . . had the same propensity to be married ... was less likely to be black (16.1% versus 18.5%), and more likely to have graduated from high school (91.7% compared with 62.9%). She scored about ten points higher on the entrance tests. Seventy percent of the women accessions during the period [FY 1973-76] were still on active duty at the end of June 1976, as compared with 64% of the male accessions."29

- After reviewing the information provided, the assistant secretary of defense made his recommendations-that the plans affecting growth presented by the Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps be accepted, but that the Army be directed to develop a plan to increase WAC enlisted strength gradually. He wrote, "In view of the reduction in the number of young men expected in the labor market in the 1980's and 1990's, it would seem prudent that the Army should pursue a more ambitious program to find ways to use more high quality women to meet their enlisted requirements. It would appear that more realistic constraints in their programs would permit significantly larger increases by 1982."30 Once again the DCSPER was overruled on plans for women in the Army.

- Few unclassified matters remain a secret very long in the Pentagon. The assistant secretary of defense's recommendations were not published until May 1977, but Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army (M&RA) Paul D. Phillips heard in March that the Defense Department would reject the Army plan and direct an increase in women's strength-to 100,000 by FY 1983. To be prepared to argue against this and to offer new alternatives, Secretary Phillips directed General Moore to develop the best possible estimates of the impact of such a decision. The

- [377]

- DCSPER promptly appointed Maj. Gen. Charles K. Heiden, commander of the Military Personnel Center (MILPERCEN), to head a general officer steering committee, which included General Clarke, that would direct the work of a task force in completing such a study by 30 June 1977.31

- The MILPERCEN task force was to evaluate the impact of expanding the numbers of women in the Army to three levels: 60,000; 80,000; and 100,000. Under an extensive data collection plan, the group evaluated information on recruiting, training, assignment, promotion, deployability, and unit readiness for the three force levels. In its report, the group stated that at the 100,000 level (85,000 enlisted, 15,000 officers), the Army could achieve the enlisted level by FY 1983 by increasing accessions from 15,000 to 26,000 annually. However, such a rapid expansion would, the task force warned, have the "most severe impact" by causing overages in year group strengths which, in turn, would create promotion, assignment, distribution, and rotation problems. Only by accessioning women at a steady rate of 15,000 annually could these consequences be avoided. The advent of more precise data, they admitted, might change this estimate of the situation. No problem was seen in increasing the strength of women officers, including those in the Medical Department, by 1983. The task force developed formulas that also showed how the numbers of women could be increased to 60,000 and to 80,000, but its final recommendation, made at the end of June, was that the Army should not commit itself to any specific force level for women.32

- The report seemed certain to arouse a dispute. Between July and November 1977, the task force's report was circulated through the Army staff and finally arrived in Secretary of the Army Clifford L. Alexander's office late in the year. By then, the secretary had also received the results of "The Content of Women in Units" field tests. In mid-December, Secretary Alexander avoided a confrontation with DOD by announcing new strength goals for FY 1983: 80,000 enlisted women and 15,000 women officers including those in the Army Medical Department. (See Table 30.) Within the Army staff, he circulated for comment the following new policies:

- -Men and women would be equally deployable.

- -Doctors could disqualify pregnant women from traveling.

- -Parents would file a child care plan that included temporary custodianship and care of minor dependents during absence from their home duty station.

- [378]

- SECRETARY OF THE ARMY CLIFFORD L. ALEXANDER, JR. (1977-1980).

- -Women who remained on active duty after pregnancy and its termination would be obliged to accept assignment anywhere in the world.

- -Men and women found to be nondeployable for unresolvable family problems would be involuntarily separated.

- These policies were staffed, approved and included in appropriate Army regulations.33

- Source: Rpt, Task Force, MILPERCEN, 30 Jun 77, sub: Final Task Force Report, Utilization of Women in the Army.

- Although it appeared to many that the Army had enough studies on women upon which to base decisions,

- General Moore directed prepara-

- [379]

- tion of still another study as soon as the task force submitted its report in June 1977. The DCSPER wanted a definitive study on how many women the Army could absorb without adversely affecting the accomplishment of its worldwide missions. In his statement of need for the study, he wrote: "There is great pressure on the Army significantly to increase the number of women in the Army. Therefore, the Army must evaluate its units to determine how many women by MOS (or specialty for officers) and grade can be assigned without reducing the units' or the Army's ability to accomplish its ground combat mission."34

- Chief of Staff Bernard W. Rogers assigned the new study, the Evaluation of Women in the Army (EWITA)

- Study, to Maj. Gen. William L. Mundie, the commander of the Army's Administrative Center (ADMINCEN), Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana. General Mundie appointed Lt. Col. Grace L. Roberts, a member of his staff, as study director with a team of twenty-eight military and civilian men and women to complete the project by 1 March 1978. General Rogers also named a twenty-member general officer steering committee, headed by General Mundie, to guide, review, and monitor the study group's progress. General Clarke was named to the steering committee.35

- For six months, the EWITA study group gathered information, reviewed policies, interviewed commanders overseas and in CONUS, and evaluated its data. Periodically, it briefed the general officer steering committee on its progress and obtained guidance in proceeding with the study. The group presented some interesting findings. Theoretically, women could fill 48,300 officer, 8,600 warrant officer, and 159,700 enlisted MOS positions, but this would require recruiting women with lower mental, physical, and educational qualifications. The study group adamantly opposed this. On the other hand, the study showed that the Army could achieve a strength of 75,000 enlisted women by FY 1983 without lowering standards. The study group recommended this course of action. It also recommended that the DCSPER establish gender-free strength requirements for each MOS; that a strength test be developed for use at the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Stations to determine MOS capability; and that physical fitness training for recruits be tailored to enhance MOS capability on a job. In lieu of using percentages to limit the number of women in units, as TRADOC proposed, normal supply and demand should be allowed to regulate the male/female personnel balance in units. The group offered other innovative proposals. It suggested that

- [380]

- expectant mothers be offered two choices-involuntary separation or a leave of absence without pay during pregnancy. It also recommended that the combat exclusion definition be simple-that women be excluded from positions whose primary function was the crewing or operation of direct and indirect fire weapons.36

- The study group's report thus contained creative solutions to the problems emerging as the content of women in Army units increased. But, at the final briefing, dissension grew. The group had considered the steering committee's guidance, but its recommendations were its own. For her part, General Clarke opposed the recommendation to offer only involuntary separation or leave of absence without pay to expectant mothers. "Neither of these options," she wrote, "is considered to be realistic or desirable. Both options are discriminatory and fail to recognize that pregnancy is a temporary disability."37

- The study's greatest foes, however, were Assistant Secretary of the Army (M&RA) Robert L. Nelson and the DCSPER, Lt. Gen. DeWitt C. Smith, Jr. Of the study's forty-nine recommendations, they nonconcurred or voted to defer action on nineteen. Army staff agencies objected to another twelve. Four of the recommendations were counter to policies announced by the secretary of the Army-his policies concerning discharge on pregnancy, combat exclusion, women's strength goals for FY 1983, and percentages of women in units. Nonetheless, the study group had been successful in presenting an objective report, and fourteen of its recommendations were approved for implementation. The report was released to the public on 22 May 1978.38

- Secretary Alexander's combat exclusion policy, a response to congressional interest, was developed during the same period that the EWITA study group was meeting. In May 1977, Senator William O. Proxmire proposed an amendment to the defense authorization legislation for FY 1978 that would allow women to serve on noncombat ships and give the secretary of defense, rather than Congress, the authority to decide whether and how women could be assigned to combat duty. Many senators

- [381]

- opposed the amendment because it raised controversial issues that could consume weeks of debate and impede passage of other key legislation. The amendment was therefore reworded to require the Defense Department to define the term "combat" and to propose any legislation needed to obtain wider utilization of military women by 30 January 1978. The latter was clearly an invitation to submit a bill that would eliminate the combat restrictions on women.39

- As the bill was being debated, Chief of Staff Rogers directed the DCSPER, General Moore, to begin work on a definition of "the combat role from which women would be excluded."40 The DCSPER staff developed the specification and sent it to the Army staff and the major commanders for review. It excluded women from

- positions in combat arms units with the function of participating in sustained armed conflict in a tactical role with the primary mission of killing, capturing or destroying an enemy force by fire and maneuver. Specifically, these combat arms units consist of Infantry and Armor battalions/squadrons, Armored Cavalry Regiments, and the support arms and services (assigned or attached) which operate in the same battlefield zone of responsibility to accomplish the aforementioned combat mission.41

- The DCSPER staff also proposed revising the definition of a Category I (combat) unit to break it into two categories: IA (Nonfemale) and IB (Interchangeable). Category IA units included: Infantry battalions, Armor battalions, Armored Cavalry regiments, direct support Field Artillery battalions, Air Defense Artillery CHAPARRAL/VULCAN battalions, Combat Engineer battalions, and Airborne divisions.42

- With few exceptions, the Army staff and major commanders concurred in the proposed definitions of combat exclusion and Category IA and IB units. General Clarke questioned excluding women from Airborne divisions, which had many positions women could fill in noncombat units that operated far from the battle zone. And, upon reconsideration, General Moore deleted Airborne divisions from the list.43

- Meanwhile, Assistant Secretary of Defense (MRA&L) John P. White sent the services two approaches to consider. Under the first, each service would define combat based on the nature of its mission (air, sea, or ground) and include an accompanying combat exclusion policy. Under

- [382]

- the second, the Defense Department would provide Congress with a general definition of combat and one of the following combat exclusion policies:

- -that no one be barred from combat based on sex (the services would use physical strength and other non-sex factors to determine eligibility for combat duty);

- -that the secretary of defense be authorized to determine which positions would be open to women subject to review by Congress (the services would support the needed legislation);

- -that the services submit a list of combat positions that Congress would close to women under a new law.44

- The Army elected to use the first option and forwarded Secretary Alexander's combat exclusion policy and this definition of combat:

- Any person serving in a combat zone designated by the Secretary of Defense is considered to be in combat. Female members of the Armed Forces of the United States may be assigned to duties in combat. They may not be assigned to job classifications where they would face the rigors of close-up combat as a regular duty and not as the incidental or occasional requirement of other duties.

- The Army further proposed that the secretary of defense designate job classifications from which women could be uniformly excluded by all services.45

- After receiving the replies from the services, Deputy Secretary of Defense Charles Duncan, on behalf of Secretary Brown, submitted the required definition to Congress. The term "combat" referred to "engaging an enemy or being engaged by an enemy in armed conflict." However, because the term involved geographic perimeters, hostile fire designations, and other complex factors, the deputy secretary recommended that the definition not be used as a basis for greater utilization of women. Army commanders, he wrote, "employ women to accomplish unit missions throughout the battlefield. The Army accepts the fact that women may be exposed to close combat as an inevitable consequence of their assignment, but does not now assign women to units where, as a part of their primary duties, they would regularly participate in close combat." The Air Force, he noted, assigned women in all its military occupations except aircrew member positions that were closed to them by law. "The Navy, however, is severely limited by current law .... The Navy cannot increase female [utilization or] strength . . . unless 10 U.S.C. 6015 is repealed or modified." In conclusion, the deputy secretary urged Congress to give the secretary of defense the authority to decide how military

- [383]

- women would be utilized and to repeal the current laws that prohibited women of the Air Force and Navy from serving on combat ships and planes.46

- Congress, however, did not approve Secretary Duncan's proposals. Instead, it passed H.R. 7431 which modified section 6015 of Title 10 to allow Navy women to serve, on permanent duty, on hospital ships and transports and to serve up to six months' temporary duty on other Navy ships not expected to be engaged in combat. The law continued to preclude women from assignment to ships or aircraft that participated in combat missions. Congress retained control over utilization of women in combat .47

- On 21 December 1977, a few days after he had sent his reply on the women-in-combat issue to the Department of Defense, Secretary of the Army Alexander officially announced the Army's exclusion policy. It applied to all women in the Army-Regular Army, Army Reserve, or Army National Guard. An all-Army message stated:

- Combat Exclusion Policy. Women are authorized to serve in any officer or enlisted specialty except those listed below, at any organizational level, and in any unit of the Army, except in Infantry, Armor, Cannon Field Artillery, Combat Engineer, and Low Altitude Air Defense Artillery units of battalion/ squadron or smaller size . 48

- The excepted list included those MOSS and specialties that had always been closed to women, such as infantryman, combat engineer, tank crewman, field artillery commander, combat aviation officer, etc. However, the changes now permitted enlisted women to serve as crew members at long-range missile and rocket sites (PERSHING, HAWK, HERCULES), as Smoke and Flame Specialists (MOS 54C), Field Artillery Surveyor (MOS 82C), and in nuclear security duties not involving recovery. Women officers could be assigned to specialties that involved long-range missiles and rockets and any aviation position except attack helicopter pilot. Both enlisted women and women officers could be assigned to some positions in the 82d Airborne Division-then an all-male division. Altogether the new policy opened fourteen new MOSs to enlisted women, eight specialties to women officers, and sixteen to women warrant offi-

- [384]

- cers. For the first time, women officers could be detailed in the Field Artillery and Air Defense Artillery branches of the Army.49

- Women still could not serve in battalion or lower units of Infantry, Armor, Cannon Field Artillery, Combat Engineers, or Low Altitude Air Defense Artillery, nor could they serve on Special Forces or Ranger teams. This prevented women from obtaining experience at the lowest working levels of the Army where men gained basic knowledge of an MOS or specialty. The rule kept women from acquiring some prerequisites for higher-level training and MOS assignments, and it effectively kept them from being exposed to direct contact with an enemy.

- In his policy guidance to the field, the DCSPER, General Smith, directed commanders to amend their manning documents so that women could promptly be assigned into new units and MOSS. He provided initial recruitment and training quotas for the new MOSS as well as procedures for women officers who wanted branch transfers to the Field Artillery or Air Defense Artillery. He asked the commander of the 82d Airborne Division to forward a plan for infusing women into his division beginning in February 1978.50

- While the new policy allowed women to be assigned to the 82d Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, a prerequisite for assignment to the division was airborne (parachute) training. Up to this time only women in MOS 43E, Parachute Rigger, had received that training, and another policy, issued in 1974, had barred MOS 43E as an interchangeable MOS.51 These rules had effectively kept women out of the 82d Airborne. After the new combat exclusion policy was issued, General Smith advised the division that only those MOS positions that actually required jump training could be identified as airborne positions. Non-airborne positions could and would be identified as interchangeable positions in combat support and combat service support units as in any other division.52 The decision was a blow to many associated with the 82d. A few retired general officer alumni of the division publicly voiced their objections to the new policy. One said he believed that casualties would increase in the division because women could not withstand the fatigue of a combat environment. Another declared, "When 12 percent of the Washington Redskins are female, I'll reconsider my decision." Despite

- [385]

- such objections, women were assigned to the 82d Airborne Division beginning in June 1978.53

- Dissension on the policy was not limited to the 82d Airborne Division. It was widespread. To quiet it, Chief of Staff Rogers sent a message to all commanders to emphasize "the Army's commitment to the integration of women." General Rogers made it clear that women would share the risks and hardships of the Army and that they would deploy and remain with their units to serve in the skills in which they had been trained. In the event of war, women would not be evacuated to CONUS. He closed with the words: "The burden which rests on leaders at every level is to provide knowledgeable, understanding, affirmative, and even-handed leadership to all our soldiers."54 Although the explanation eliminated public objection to the policy, few men in combat units reconciled themselves to the more liberal policies affecting assignment of women.

- Knowing she was the last director of the Women's Army Corps, General Clarke felt a deep sense of responsibility to the women she represented, past and present. She wanted to ensure that someone would follow her on the Army staff to speak for women's interests. Later she said, "I thought it imperative that the Army continue to have a senior military spokeswoman somewhere in the hierarchy to ensure that policies take into consideration women's status, special needs (particularly uniforms), and their opportunities to have viable careers."55 Therefore, soon after she took office in 1975, General Clarke had taken the initiative to establish a position for a woman general officer on the Army staff to serve as adviser and spokeswoman when the director's position vanished. The DCSPER, then Lt. Gen. Harold G. Moore, agreed to let her prepare a plan for this purpose.56

- General Clarke submitted several proposals for accomplishing her goal. Her first plan proposed establishing an additional position, that of deputy, with the rank of brigadier general, in the Directorate of Military Personnel Management, ODCSPER, to be filled by a woman officer. The primary, but not sole, duty of this deputy would be to head a Women's Advisory Branch located within the directorate that, like ODWAC, would assist the Army staff in preparing, advising, or speaking on women's issues, except those involving the special branches: the Medical

- [386]

- Department, Chaplain's Branch, and Judge Advocate General's Corps. This woman would also assist in developing personnel policies for both men and women. On women's matters, she would have direct access to the secretary of the Army and to the chief of staff. General Clarke's plan thus retained a women's adviser, involved the adviser in both men's and women's personnel management, and placed her in an ODCSPER directorate. If she had recommended the women's adviser be in a renamed directorate, little change from ODWAC would have been apparent. If she had recommended the position be located in the only other appropriate ODCSPER directorate, Human Resources, the adviser's duties could have become entangled with those of the director of Equal Opportunity Programs. To allow time to have the new arrangement in effect before DOPMA passed, she recommended the change take place on 1 October 1977-approximately twenty months away.57

- Before circulating her plan, General Clarke took it to Maj. Gen. John F. Forrest, the director of the Military Personnel Management Directorate. To her dismay, General Forrest did not want another deputy, and he said that if he did he "would have difficulty defending two brigadier general officers to subsequent manpower surveys." He recommended that the position of the senior military woman adviser be placed in the Directorate of Human Resources or be located in the Army's Military Personnel Center, Alexandria, Virginia.58 Without General Forrest's support, General Clarke knew that neither the other directorates nor the DCSPER would approve the plan. She withdrew the proposal.

- In a few months General Clarke came up with another plan. This time she proposed a senior woman officer and a small staff to be called the Office of the Adviser for Women in the Army to replace the WAC director and her staff. With only a change in title, the ODWAC would remain intact with its duties, responsibilities, and staff. General Clarke also considered merging ODWAC with the Office of Equal Opportunity or making the new office a separate division within the Human Resources Directorate, but she rejected these ideas because they diminished the role of the women's adviser.59 This time, she distributed copies of the plan to the ODCSPER directorates and the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (M&RA) for comment. It was not well received. The director of human resources called it an attempt "to perpetuate the myth that only a senior woman officer can advise on women's affairs" and said it negated

- [387]

- the Army's efforts to fully integrate women in the Army.60 The director of military personnel management said it simply continued ODWAC under another name, and he questioned the necessity and desirability of a full-time adviser for women in the post-DOPMA environment. Women's views would be considered equally with men's under the DCSPER's management system. Another director felt the new office would emphasize the adviser's preoccupation with women's affairs when she should be involved in actions regarding men and women. The Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army (M&RA) also dissented, but it did recommend a dual-hat position for a woman general officer as director or deputy director of a DCSPER directorate and as adviser to the Army staff on women's matters. By the end of 1976, the plan to replace ODWAC by renaming it had gathered so many nonconcurrences that General Clarke withdrew it.61

- The "lame duck" status of ODWAC made it progressively harder for General Clarke to influence action, and compounding that hindrance was the resentment many male staff officers felt toward women entering the U.S. Military Academy and other all-male bastions like the 82d Airborne. As study followed study on women in the Army, many officers felt too much of their time had to be devoted to women's actions, too little to men's. Nonetheless, General Clarke and her staff did influence a number of policy changes. One, in November 1975, declared that women who were pregnant were ineligible for overseas assignments as individuals or as members of a deploying unit. Another required commanders to provide formal counseling to pregnant women and to personnel with dependents to ensure they knew their options and responsibilities.

- By April 1977, the director's office was able to put together a purposeful symposium, "Women in the Army," during which representatives from all major commands, the other services, and the Office of the Secretary of Defense discussed women's issues and their resolution. As one result of such pressure, and the director's specific request, TRADOC initiated a complete review of requirements for women's field clothing and equipment, including sizing and modification of the current patterns. For the DCSPER, General Clarke and her staff helped develop a childcare program for implementation in the United States and overseas.

- On an even more fundamental issue, in 1976, the director had assisted TRADOC in developing a rape prevention lesson plan, which was later distributed to all major commands for presentation to female military

- [388]

- personnel along with a commercially produced training film, Rape, A Preventable Injury. TRADOC also developed Army policies and procedures for the treatment of rape victims with consideration for the legal, medical, and law enforcement aspects of these cases.

- The director's office also helped to establish a program for confinement of female felons with sentences of imprisonment for less than six months. Confinement locations for women included the U.S. Army Retraining Brigade, Fort Riley, Kansas. The program was later expanded to include women offenders sentenced to prison for six months or more. These women could be confined at the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, beginning in February 1978.62

- Despite interruptions for staff visits around the world, WAC recruiting, work on women's studies, and other policy matters, General Clarke continued her attempts to establish a general officer woman adviser to succeed her. After further deliberation with her staff about the placement of the adviser, General Clarke went back to her original proposal. Her original proposal had been rejected by the director of the Military Personnel Management Directorate, but she decided that, with a few revisions, it was the best plan. On 1 February 1977, she circulated the plan for comment. The plan recommended that her functions be transferred to the Directorate of Military Personnel Management and combined with those of the existing deputy director of that office. The deputy director, designated for "fill by a woman only," would be given the added title Senior Adviser on Army Women (except those in special branches), and a WAC Advisory Office, made up of the ODWAC staff, would assist the deputy in fulfilling these duties. In future years, when women's matters no longer occupied such a large share of the deputy director's time, the position could be declared interchangeable. General Clarke did not recommend that this deputy have direct access to the secretary of the Army and the chief of staff on women's matters.63

- The new proposal fared no better than the others. The new chief of military personnel management, Maj. Gen. Paul S. Williams, Jr., did not want his deputy director performing the functions of the director of the WAC nor did he want a Women's Advisory Office in his directorate. Instead, he recommended that the director's personal duties-giving speeches and representing the Army in women's matters-be assigned as an additional duty to the senior woman officer on the Army staff. The director's other functions could be distributed among appropriate branches within his directorate. General Clarke tried to dissuade him from the latter by advising him that the extensive work load of her office

- [389]

- could be managed more easily from a central point than if it were dispensed throughout a directorate. He was not convinced.64

- Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army (M&RA) Phillips recommended that a woman general officer fill the next vacancy in an appropriate general officer position in ODCSPER and that she be named Senior Adviser on Women in the Army (less those in the Medical Department). As the senior adviser's tour ended, the next woman general to be assigned to a directorate within ODCSPER would be named as the adviser. The Women's Advisory Office would follow her to whatever directorate she was assigned. Though the concept was good, it required moving the Women's Advisory Office, at least organizationally, to wherever the senior adviser was. General Clarke thought it was too risky to proceed with a plan dependent upon general officer vacancies that could disappear overnight.65

- General Clarke deliberated at length on the alternatives proposed but she would not revise her plan. She strongly believed the senior Army woman and her staff needed to be located in the Directorate for Military Personnel Management where personnel plans and policies were written. She regrouped and prepared a new campaign for her plan. Before she began, however, the chief of staff's management director, Maj. Gen. Richard G. Trefry, plucked the matter from her hands.

- General Trefry had been directed to review the general officer spaces on the Army staff with a view to reducing them. In early April 1977, he told the chief of staff that it was "difficult to rationalize or justify the continuance of the [DWAC] office as it is now constituted." He referred to the fact that all WAC officers had been transferred to other branches, that WAC detachments had been integrated with male units, that the WAC Center and School had been deactivated, and that most personnel and administrative procedures were alike for men and women. He believed that women general officers should not be confined to the ODWAC, that the time had come for the Army to "make more normal use of this general officer space," and that there were "several billets wherein a female general could be usefully employed."66 Chief of Staff Frederick C. Weyand agreed. On 23 April 1977, he directed the DCSPER to prepare legislation to eliminate the DWAC position. In his memo he noted that he believed that "the Army should now take the

- [390]

- positive actions necessary to officially lay the WAC to rest and formalize its members' integration in the Army. Gen. Kerwin is amenable."67 A former DCSPER and former commanding general of both TRADOC and FORSCOM, General Kerwin had been vice chief of staff since October 1974.

- The DCSPER, through the director of military personnel management (DMPM), asked the legislative liaison chief to prepare legislation to disestablish the Women's Army Corps and the offices of the director and the deputy director and to delete portions of the law that precluded women from being assigned to other branches of the Army and any other laws that impaired equal treatment of Army women. Surprisingly, the DCSPER now ignored earlier advice received from the Defense Department not to initiate any new legislation that was already included in DOPMA. To indicate the high priority on the project, the DMPM told the chief of legislative liaison, "During a staff principals meeting on 15 May 77, the Chief of Staff directed earliest feasible disestablishment of the WAC."68

- When the proposed legislation was sent to the Army's judge advocate general, Maj. Gen. Wilton B. Persons, for comment, he suggested a means to rapidly accomplish the goals of the legislation. He cited a law that permitted the secretary of defense to transfer or vacate a statutory position or function simply by notifying Congress of his intentions. If Congress did not object within 30 days while in session, the secretary's reorganization order was considered approved.69 Secretary of the Army Alexander passed the idea on to Secretary of Defense Brown. Secretary Alexander also noted that the director of the WAC and her staff would be transferred to other duties and that their functions and personnel spaces would be distributed within ODCSPER. A senior woman officer in ODCSPER would advise the Army staff on women's matters (except those in the special branches-Medical, Chaplain's, and JAG).70

- The Army's memo reached Secretary Brown at an opportune time. He had just prepared a reorganization order, using the procedure suggested by the JAG, to eliminate six assistant secretaries within the Department of Defense. He simply added the positions of the director and deputy director of the WAC to the order, attached legislation to eliminate the

- [391]

- WAC as a separate corps, and had an emissary discuss the entire package with members of the Senate Armed Services Committee. From this he learned that an overcrowded agenda would prevent the committee from considering the package before Congress adjourned in December 1977.71

- On 7 March 1978, Secretary Brown formally forwarded to Congress his reorganization order abolishing the eight positions. However, he withheld the legislation to eliminate the WAC. Regarding the WAC positions, he wrote: "This action which was recommended by the Secretary of the Army, reflects the integration of women in the Army's activities and is consistent with current arrangements in the Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. It recognizes the role of women as full partners in our national defense, with full opportunity to progress with their male counterparts." He also noted that the other services had abolished their women's director positions. 72

- On 20 April, thirty consecutive legislative days after Congress had received the reorganization order and during which time it had made no objection, the order went into effect. The Army immediately issued a general order abolishing the positions of the director and deputy director of the WAC and the Office of the Director, effective 20 April 1978. Secretary Alexander made the announcement on 24 April, and the director's office planned the disestablishment ceremony.73

- The ceremony was held on 28 April in the DOD press room at the Pentagon. Several members of Congress, three or four former directors of the WAC, members of the defense and Army staffs, and representatives of the news media attended. Secretary Alexander was the principal speaker. After a few remarks, he called on General Clarke. Her words carried the news that the change would increase opportunities for women. "This action today in no way detracts from the service of WACs who have been pioneers-in fact it honors them. I view this action today as the culmination of everything the members of the Women's Army Corps have been striving for for thirty-six years. The significance of the abolishment of the Office of the Director . . . is the Army's public commitment

- [392]

- . . . to the total integration of women in the United States Army as equal partners."74

- At the conclusion of her talk, Secretary Alexander took the floor. This time he announced that General Clarke would be reassigned as the commanding general of the Military Police School/Training Center at Fort McClellan on 18 May; it was the first time a woman had been named to command a major Army post. And because she would replace a major general, it appeared that she would also become the first two-star woman general in the Army or the other services. News of the assignment and anticipation of her promotion helped remove some of the sadness, if not resentment, felt by many WACs upon losing the director's position.

- Although no poll was taken, probably 50 percent of the WACs favored dissolution of the Corps and the office of the director. They believed this would free them from an inferior status and increase their value as career soldiers. Predictably, the older WACs held a more sentimental view. They wanted to retain their Corps, their insignia, their director, and their historical image as WACs. To them, the ceremony signaled the end of an era-their era.75

- In her End of Tour Report General Clarke praised the Army's continuing progress in obtaining and utilizing the services of women. She recounted progress in increasing the strength of women in both the active and reserve components, in assigning women to nontraditional MOSs, in opening ROTC and the U.S. Military Academy to women, in combining basic training for men and women and one-station unit training, and in developing combat exclusion guidelines. During her tenure the Army had standardized enlistment age, military obligations, overseas-tour lengths, housing criteria, and disciplinary and confinement policies. She had personally ensured the implementation of policies affecting pregnant women and women with dependents, including formal counseling and child-care programs.

- General Clarke's final recommendations to the chief of staff and the secretary of the Army reiterated her concerns. Catch-up training should be given women in defensive weapons training to overcome reported

- deficiencies. A new physical training program held promise of increasing

- [393]

- .

- women's fitness level, but it needed to be monitored. Many pregnancy and single-parent problems remained unsolved; more time was needed to develop innovative solutions to them. Men as well as women should receive instruction in sex education, birth control, and rape prevention to help lessen these particular problems. She also asked the secretary to be vigilant against a decline in women's command positions and a further limiting of the number of colonel and brigadier general promotions given women.76

- Upon General Clarke's departure, the DCSPER dissolved the director's office and transferred her staff. The personnel spaces went to the branches within the Directorate of Military Personnel Management that would perform the residual functions of the ODWAC staff. The chief of staffs management office reduced the grade of the director's space to colonel before transferring it to DMPM. The Army Uniform Branch in the Directorate of Human Resources Development received the enlisted (E-9) space and its incumbent, Sgt. Maj. Beverly E. Scott.77

- [394]

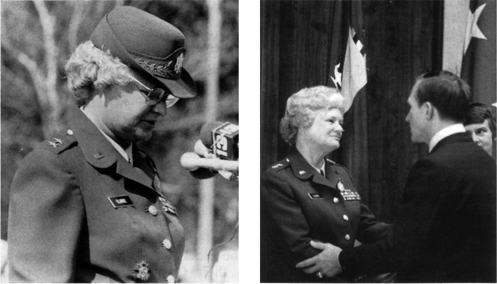

- The DCSPER did not appoint a senior woman officer as adviser on women's matters. The speaking engagements and representational duties formerly assigned the DWAC went to Col. Lorraine A. Rossi while she was in ODCSPER as director of the Army's equal opportunity programs (1977-1980). Several other women colonels assisted her.78 Meanwhile both the military and the civilian communities welcomed General Clarke back to Fort McClellan, this time as commander of the U. S. Army Military Police School/Training Center and Fort McClellan. Promoted to major general on 1 November 1978, she served as post commander for 27 months. In August 1980, she was transferred back to the Pentagon to be the director of the Human Resources Development Directorate in ODCSPER. When she retired on 31 October 1981, after serving over thirty-six years on active duty, she selected Fort McClellan, the former home of the Women's Army Corps, as the site for her retirement ceremonies. As friends, family, former WAC comrades, and over 3,000 soldiers and civilians at Fort McClellan participated in her retirement parade, Assistant Secretary of the Army (M&RA) Harry N. Walters presented General Clarke with the Distinguished Service Medal. "I am," she told the gathering, "a fortunate soldier. I have the same love for the Army today as I had the first day I put on my uniform as a private at Fort Des Moines in 1945 . . . . I leave the Army today feeling that I have been all that I could be." The Army's recruiting theme, "Be All That You Can Be in the Army," never had a more appropriate representative.79

- Between 1973 and 1978, separate WAC training and command elements had vanished so gradually from most Army posts that their absence was slightly noted. If these events, including the loss of the Office of the Director, WAC, had occurred within one year, they might have aroused an outcry by WAC members, but the lapsed time diffused the impact. Through correspondence and speeches, General Clarke, like her predecessor, kept the members of the Corps and the former directors advised of the Army's intentions and progress of those plans. In December 1975, she told a group of active and retired WAC and other branch officers, "Plans are being developed to phase out the Office of the Director, WAC, and to repeal the legislation which established the Women's Army Corps as a separate entity. This should occur within two years."80 Few women complained to General Clarke, wrote letters to their congressmen,

- [395]

- or to the service journals or newspapers. General Clarke had tried to obtain an official position for a women's adviser at the Pentagon but had been unable to do so. Later, in 1980, she initiated action to obtain a service ribbon for members of the WAC to wear who had served in the Corps. The chief of staff disapproved it because he felt that other existing service awards covered the same period and the proposed ribbon would duplicate them.81

- In July 1978, Secretary of Defense Brown sent Congress the draft legislation, which he had held back earlier, to discontinue the Women's Army Corps and delete related existing laws. The proposed DOPMA contained similar provisions, but that legislation had become controversial and its passage in the near future was doubtful. (It became law in 1981.) In an effort to hasten discontinuance of the Corps, Secretary of the Army Alexander wrote Senator William O. Proxmire on 23 September, urging action on the proposal. "This letter is to reconfirm my personal support for the proposed legislation to amend Title 10, United States Code, to abolish the Women's Army Corps (WAC). The WAC legislation is of greatest importance to the Army in achieving full utilization of men and women to the maximum extent of their talents."82

- With this strong encouragement, Senator Proxmire proceeded. He proposed an amendment to the FY 1979 Defense Procurement Authorization Bill which would delete the appropriate sections of Title 10 and accomplish the actions requested by Secretary Brown. Senator Proxmire reassured the Senate Appropriations Committee that the amendment would not permit women to be assigned to the combat arms or go into combat, but it would eliminate a long-existing unfairness in the law. "Imagine," he asked, "a separate personnel system for Blacks or Catholics or Chicanos. The country would not stand for such a thing .... The Women's Army Corps is the last vestige of a segregated Military Establishment .... There is no separate corps for female Naval personnel or Air Force personnel. All that the Army is asking is that it be allowed to streamline its system as the other services have done." The senator concluded his argument for the bill with praise for the members of the Corps. "WACs have served this country with great courage and effectiveness. Women will continue to serve our country in the military-but in the mainstream of the Services, without restrictions on their service, without special privileges, or special obstacles to their advancement." 83

- Senators John C. Stennis (Mississippi) and John G. Tower (Texas), members of the Armed Services Committee, objected to the WAC issue's

- [396]

- being lifted out of other pending legislation and being attached to the appropriations bill. A motion to table the amendment, however, was defeated. The committee, by voice vote, passed the amendment and it was added to the bill.84 The Senate approved the FY 1979 Defense Procurement Authorization Bill on 26 September, and the House approved it on 4 October 1978.85

- On 20 October 1978, President Carter signed the bill into law. PL 95584 abolished the Women's Army Corps as a separate corps, the positions of the director and deputy director, the separate WAC Regular Army promotion list, officer assignments only in WAC branch, and other policies and programs based on a separate women's corps. The Department of the Army then issued General Order 20 which discontinued the Women's Army Corps, effective 20 October 1978.86

- The elimination of the Women's Army Corps ended the charge against the Army that it discriminated against women by keeping them in a separate corps. The women no longer had a separate and distinctive identity with their own corps, their own directors, their own insignia the Pallas Athene. Thirty years after integrating women into the Regular Army, the women were fully assimilated into the permanent establishment.

- [397]

| Army | Navy | Air Force | Marine Corps | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual FY 76 | For FY 82 | Actual FY 76 | For FY 82 | Actual FY 76 | For FY 82 | Actual FY 76 | For FY 82 | |

| Officer | 4.8 | 9.0 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 8.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Enlisted | 43.9 | 50.4 | 19.2 | 28.5 | 29.2 | 48.2 | 3.1 | 6.7 |

| Total | 48.7 | 59.4 | 21.7 | 33.3 | 34.0 | 56.8 | 3.4 | 7.3 |

| Fiscal Year | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Officers (All branches) | 8,890 | 10,178 | 12,702 | 13,842 | 15,000 |

| Enlisted Women | 51,132 | 58,620 | 67,566 | 77,218 | 80,000 |

| GENERAL CLARKS Speaks at her retirement review, WAC Center, Fort McClellan, 31 October 1981 | ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF THE ARMY (M&RA) HARRY N. WALTERS at retirement ceremonies for General Clarke, 31 October 1981 |