COL. ELIZABETH

P. HOISINGTON, DIRECTOR, WAC, meets with her predecessors at the Pentagon

to make a film commemorating the 25th anniversary of the WAC Left to right:

Cols. Oveta Culp Hobby, Westray Battle Boyce Long, Elizabeth P. Hoisington,

Emily C Gorman, Mary A. Hallaren, and Mary Louise Milligan Rasmuson, 14

March 1967.

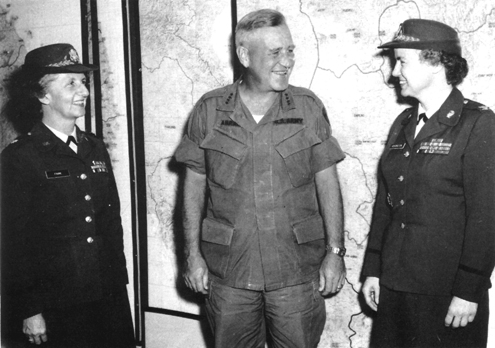

THE FIRST TWO

MILITARY WOMEN TO ACHIEVE GENERAL OFFICER RANK, Brig. Gen. Anna Mae

Hays, Chief of the Army Nurse Corps (left), and Brig. Gen. Elizabeth

P. Hoisington, Director, WAC (right), with Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower

on their promotion day, 11 June 1970.

In 1969, a national political

force that had appeared to be spent revived, and the women's rights

movement again began to achieve prominence. Three years after women

won the right to vote in 1920, proposals for an Equal Rights Amendment

began to be discussed in Congress. Although the draft amendment made

little progress over the decades, federal legislative and executive

branch actions in the 1960s eliminated some forms of gender

discrimination. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 ensured equal pay for equal

work for women employed in jobs controlled by interstate commerce

laws. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited sex

discrimination in employment unless gender was a bona fide

occupational qualification. Executive Order 11246, 24 September 1965,

prohibited sex discrimination in the federal government or in

employment generated by federal contracts.

As the women's movement grew,

it attracted wide public interest and began to change some American

attitudes and social customs. The mill-

[232]

tant leaders of the movement

sought media attention by organizing women to strike against housework

and waiting on spouse and children, to seek entry into all-male clubs

and meetings, and to boycott businesses and cities that discriminated

against women in employment or promotion. These women demanded that

laws and customs that restricted their opportunities, roles, and

freedom be eliminated. Women in all walks of life joined the movement,

and its political influence grew. Even those who had initially laughed

at the attention-getting antics of some feminists were compelled to

take note when the courts upheld many of their claims. The courts

forced businesses and governments to amend discriminatory laws,

policies, customs, and regulations and to compensate women

retroactively when sex discrimination had deprived them of promotion

and pay. This side of the women's movement appealed to many,

particularly the younger, members of the women's services.

The women's movement had a

decided influence on American life. It presented society with more

liberal ideas regarding women's work, dress, and legal status. Society

accepted those ideas and, with them, changes in long-standing social

customs, relationships, and moral standards. By the late 1960s, many

Americans accepted unwed mothers, illegitimate children, and couples

who lived together without being married.

Few women in the country could

have been considered more likely to reject many of these developments

than the conservative, traditionminded WAC leadership. To them,

changes that appeared to make women more like men meant a decline, not

an improvement, in the status of women. But there was no escaping the

momentum of the women's movement and the acceptance of its goals by

most politicians.

WAC entry and retention

standards came under examination in 1970. The commander of the Army

Recruiting Command, Maj. Gen. Donald H. McGovern, wrote in May 1970,

"The movement for more liberal moral standards and the rising

emphasis toward equality of the sexes require that this command be

prepared to answer an increasing number of questions and charges

concerning the validity of allegations of discrimination against

female applicants for enlistment."39

He asked the DCSPER why

waivers could not be considered for women who had illegitimate

children or a record of venereal disease (VD) when these factors did

not bar men from enlistment or even require submission of a waiver.

The director of the WAC and

the director of procurement and distribution, ODCSPER, Brig. Gen.

Albert H. Smith, Jr., prepared the reply to General McGovern. Arguing

that American society demanded higher moral character in women, they

wrote, "Having a history of venereal

[233]

disease or having had a

pregnancy while unmarried is an indication of lack of discipline and

maturity in a woman." WAC enlistment standards, their reply

continued, were designed to ensure that the Corps accepted as few

risks as possible in mental, physical, and moral qualifications.

Employers in industry tailored employment qualifications to fit job

requirements, and the WAC established enlistment qualifications

"based on our requirements for service, wearing the uniform, and

the necessity to maintain an impeccable public image." 40

While General Hoisington

believed that granting the first waiver would open the door to endless

requests for others, she also believed that if a regulation were no

longer valid, it should be rewritten. In August 1970, Maj. Gen. Leo E.

Benade, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve

Affairs (DASD M&RA), reintroduced the subject. He had received

complaints from members of Congress, pressure groups, and ordinary

citizens, alleging that the military services discriminated against

women by barring them, but not men, from enlistment or retention if

they had had unwed pregnancies or a history of VD. Several court

actions involving the pregnancy rules had been initiated. In one

publicized case, an unmarried, pregnant Air Force nurse obtained a

court order that prevented the Air Force from involuntarily

discharging her. The Air Force appealed, but over a year passed before

the court ruled that the service could discharge her on grounds of a

compelling public interest in not having pregnant female soldiers in a

military unit. When the officer appealed that decision, the Air Force

did not fight the case by then it had decided to allow pregnant women

to submit waivers to remain on duty. The officer's request for a

waiver was subsequently approved, and she remained on duty.41

General Benade met with his

service counterparts to discuss these developments. He asked their

opinions on whether the services discriminated by barring a woman from

enlistment or retention if she had had a child out of wedlock, but did

not bar the putative father. General Benade hinted at his position,

"Congress provided that we cannot enlist the insane, the

intoxicated, the deserter, or the convicted felon. But beyond that

perhaps we should not include, as a class, the unwed mother."42

Deputy Assistant Secretary of

the Army for Personnel Policy and Programs John R. Kester, who was a

lawyer, reviewed the issues presented. He believed that, as a matter

of equity, the Army should not bar

[234]

married women or unwed mothers

from initial enlistment or appointment or from retention. Nor should

pregnancy and parenthood cause automatic dismissal from the service.

On 8 October, he directed the DCSPER "to amend and standardize

Army Regulations pertaining to ... enlistment, appointment, retention,

and separation of female members" on marriage, pregnancy, and

parenthood.43

He further asked that the proposed changes be on his

desk within a week. The DCSPER, Lt. Gen. Walter T. Kerwin, Jr., asked

for time to study the impact of the proposed changes on the budget,

housing, medical care, morale, and personnel management. In addition,

the proposal required coordination with the surgeon general, the chief

of the reserve components, the Office of Personnel Operations, the

director of the WAC, and the judge advocate general. He promised a

report on 15 January 1971 and appointed a task force of

representatives from those offices to prepare the study.44

Before the task force held its

first meeting, Under Secretary of the Army Thaddeus R. Beal asked the

DCSPER to revise Army regulations immediately to allow waivers for

some moral and administrative disqualifications affecting the

enlistment and retention of women: history of VD; civilian court

conviction; more than 30 days' lost time for being AWOL; illegitimate

pregnancy; marriage prior to an initial enlistment in the Army; or

responsibility for a child under 18 years old. Mr. Beal rejected the

idea of a new study, saying, "Although I understand that the

Staff has suggested a study in this area, I do not believe such an

effort would add significantly to what we already know; in any event,

the matter is urgent." As director of the Army Council of Review

Boards, Mr. Beal supervised the boards that decided on appeals of

discharges and other separation actions. He asked for the regulatory

changes so that the Army could avoid future embarrassment and possible

adverse court rulings and could keep its polices in line with those of

the other services. "This would not," he said, "require

any radical change in policy but would allow the Army to decide each

case individually."45

In the midst of much internal

controversy, the task force revised the regulations following Mr.

Beal's directions. General Hoisington strongly disagreed with almost

every revision. Regarding waivers that would allow married women

without previous service to enter the WAC, she wrote, "The Army

is not a suitable side job for a woman who is already

[235]

committed to maintaining a

home, a husband, or a child." Women who had unmarried pregnancies

were, she said, "likely to be disciplinary or adjustment

problems." She would not allow waivers for women with children

under eighteen and maintained that "a woman with children is a

liability to the Army because she is not free to travel."46

Maj.

Gen. Frank M. Davis, Jr., the director of military personnel policies,

also disapproved waivers to enlist unwed mothers and women with a

history of VD. He felt waivers condoned permissive personal behavior .47

And, despite his agreement with the objections, the acting

director of procurement and distribution, Col. J. K. Gilham,

recommended to General Kerwin, the DCSPER, that the Army "comply

with a second firm directive from Secretarial level."48

With one exception, the DCSPER

included in the revised regulations all the waiver provisions that Mr.

Beal had requested. Vice Chief of Staff Bruce Palmer, Jr., concurred

and withheld the waiver provision that would allow women without

previous service to enter the Army if they had responsibility for

minor children. For equity, he recommended that the provision also

apply to males without prior service. "Certainly, the Army would

be a more flexible, mobile, and responsive organization if E-1

enlistments are not burdened with responsibility for children under 18

years of age."49

He also forwarded General Hoisington's

comments, which said in part:

The recent acceleration of the

women's liberation movement and the publicity it attracts from the

news media, in my opinion, threatens to overwhelm good sense and

perspective in the management of Women's Army Corps personnel. Several

decisions have already been made on individual cases and others are

under consideration which directly undermine the effective employment

of women in the WAC and which are counter to our reason-for-being in

the United States Army.

I feel obliged, therefore, to

warn against any rash, unwarranted, and unsound decisions affecting

the enlistment, utilization, retention, and cost effectiveness of

women in the Army.

The Army has an obligation to

its current and former WAC members, to parents who have entrusted

their daughters in our keeping, and to itself, to advance the

standards of morality, the effective utilization, and morale of WAC

personnel. As Director of the Women's Army Corps, and as the spokesman

for thousands of

[236]

women who have served and are

serving in our Corps today, I feel a deep moral conviction and

obligation to make my objections known and understood. I cannot be

silent on issues and decisions affecting the Women's Army Corps that

do not consider twenty-eight years of experience we have had in

judging the morale, utilization, and discipline of Women's Army Corps

personnel. For this reason, I desire my comments be forwarded to the

Chief of Staff and the Secretary of the Army for consideration and I

stand ready for a personal audience to present further arguments

supporting the actions below which are vital to the existence of the

Women's Army Corps.50

Since senior officials usually

resolve differences of opinion in conferences, General Hoisington

expected a summons to meet with Mr. Beal or Mr. Kester. Several weeks

passed without a call. With General Kerwin's permission, she wrote

directly to Mr. Beal on 24 November 1970. Her apprehension had been

heightened by the news that the funds and spaces would soon be

authorized for an 80 percent WAC expansion to support President

Nixon's call for an all-volunteer Army. Such an expansion could lead,

as it had in World War II, to a dispensation of waivers so liberal

that the quality of WAC recruits would fall. In her memo to Mr. Beal,

she argued that women's standards did not discriminate simply because

they did not parallel men's. They differed because the WAC needed

recruits of a quality higher than that needed in most of the men's

branches. "These standards," she wrote, "were set to

sustain and improve the development of a women's force whose members

exemplify the highest standards of professionalism, integrity, and

moral character in the Armed Forces." Experience had shown, she

continued, that in the stress of a buildup, quality falls, and she

could no longer concur in the proposed WAC expansion unless she could

"be assured that the quality of women in the Army would not be

adversely affected by changes made in entry, retention, and separation

policies for members of the Women's Army Corps."51

When General Hoisington's memo

arrived, Mr. Kester and Mr. Beal were reviewing the revised waiver

regulations. The memo delayed their response to the revisions, and

they met with the director on 2 December. At the meeting, she urged

them to maintain WAC standards as the regulations stood, without

waiver and without change. Unsuccessful in this, she reluctantly

proposed a compromise. She would accept the submission of waivers for

a history of VD and for thirty days of lost time, if they did not

insist on waivers for women desiring entry or retention with children

born out of wedlock or with children under eighteen. This effort, too,

failed. General Hoisington recalled the conference: "It took only

a few minutes to discover they had their minds made up to allow

[237]

waivers for everything. Still,

I gave forth my best arguments and pleaded with them not to begin the

degradation of WAC standards. We went back and forth on the

qualifications and they discarded every reason I had for keeping

them." Finally, when they would not consider how many unwed

pregnancies should disqualify a woman for entry or retention, General

Hoisington gave up, and the meeting ended.52

The next day, 3 December, Mr.

Beal directed the DCSPER to authorize waivers for moral , and

administrative disqualifications for women entering the Army. He also

vetoed Vice Chief of Staff Palmer's request to defer the decision to

provide waivers for men as well as women with minor children.53

The outcome reflected a

fundamental divergence, not only between older and newer ideas on

women's military role, but also between military and civilian

officials. Being lawyers, Mr. Beal and Mr. Kester differed with

General Hoisington on the use and enforcement of Army regulations.

They wanted the regulations to protect the Army from lawsuits and to

give the service the greatest amount of flexibility in accepting and

retaining personnel. Their roles required them to uphold the rights of

individuals who were, had been, or wanted to become members of the

Army, Navy, or Air Force. To achieve those goals in the environment of

the early 1970s, they needed the authority to waive disqualifications

for entry and retention-except for insanity, drunkenness, desertion,

or felony convictions, as already provided by law.

After the DCSPER received Mr.

Beal's order, the Directorate of Military Personnel Policies, ODCSPER,

circulated its proposed policies.54

General Hoisington again refused

to concur. In a memo addressed to Mr. Beal, she wrote: "In

reviewing the DCSPER proposals on separation regulations for women in

the Army, I can only conjecture that they are based on the notion that

the Army discriminates against women by requiring their separation

when they become pregnant. It is a fact that a woman has freedom of

choice in deciding whether or not she will become pregnant. If she

elects, therefore, to become pregnant and deliberately incapacitates

herself for retention, how has the Army discriminated against

her?" Knowing that her objections would be ignored, she asked the

under secretary at least to establish firm guidelines on approving

waivers for retention of unwed mothers and to continue mandatory

discharge of women who were pregnant upon entry into the service or

[238]

who had abortions or

miscarriages while on active duty. She did not believe that a woman

should be rewarded by retention in the service after she had an

abortion, when women who rejected abortion and proceeded with their

pregnancies were mandatorily discharged. To her, this was

discrimination, even though women forced out of the service on account

of pregnancy could apply for reenlistment after two years.55

A few weeks later, General

Palmer asked for a conference with the DCSPER and the DWAC to discuss

WAC standards. At issue was a request for retention submitted by an

unmarried enlisted woman who had had an abortion. The woman's WAC

detachment commander had recommended discharge, based on the woman's

poor performance of duty; her battalion commander had recommended

retention. When General Hoisington reviewed the case, she agreed with

the detachment commander. In the director's opinion, it was better to

discharge the woman immediately because the woman was a combined poor

risk (performance of duty and moral character) and retention set a

precedent for similar cases. The director also knew the Army did not

want to rule on how many abortions should be allowed before discharge.

Mr. Kester overruled General Hoisington and approved the woman's

request for retention.

On 29 March 1971, at the

conference requested by General Palmer, General Hoisington once again

explained her view of the impending changes in the regulations. She

expressed concern that the quality of women entering and being

retained in the Corps would decline and that this decline would

diminish the Corps' image and its ability to recruit women of high

mental, moral, and physical qualifications. The vice chief listened to

General Hoisington's views and agreed with her insistence upon

retaining high standards. Nonetheless, he felt that the social and

political environment would, today or tomorrow, require the Army to

change its policies. He could not, therefore, recommend that Chief of

Staff Westmoreland initiate a challenge to the policies directed by

Under Secretary Beal. He concluded by assuring General Hoisington that

WAC requests for waivers would be sent to her for review and that her

recommendations would receive full support under the new regulations.

This assurance was faint comfort to the director, who had just seen

Mr. Kester overrule one of her decisions. 56

A message to major commanders

announced the new policies. Effective 9 April 1971, women could

request waivers for disqualification from entry and retention because

of pregnancy, terminated pregnancies, and

[239]

parenthood.57

The new

policies also affected women in the Army Medical Department, where the

views of the leadership differed markedly from those of the WAC.

Surgeon General Hal B. Jennings, Jr., had not opposed the new

policies, declaring that waivers recognized "the principles of

equality" and eliminated "an inflexible attitude toward

changing societal patterns."58

Following the Army's lead, the

other services implemented similar waiver policies.

Between 1950 and 1970, the

number of illegitimate births in the United States had almost tripled,

indicating a change in American social and moral standards.59

In line

with this trend, on 16 July 1970, the assistant secretary of defense

for health and environment transmitted a new policy on abortion to the

services. The assistant secretary advised the services' surgeons

general that abortions could be performed in their hospital

facilities, regardless of the laws of the state in which they were

located. A woman needed only to prove to a doctor's satisfaction that

the abortion was necessary for her long-term mental or physical

health.60

The 1970 policy did not affect

the WAC. Army regulations still provided that women would be

involuntarily discharged as soon as they became pregnant. If an unwed

woman had an abortion before her discharge date, she was mandatorily

discharged; a married woman could request retention on duty. General

Hoisington became deeply interested in the abortion issue when it

appeared that the new waiver policies would allow any woman who had

had an abortion to request retention. In February 1971, she asked

Judge Advocate General Kenneth J. Hodson for an opinion on whether the

Army could prohibit abortions for unmarried WACs under 21, could

require their parents' consent to the operation, or could deny a woman

an abortion if her pregnancy predated her entry into the Army. General

Hodson decided that after parents had given their consent to the

initial enlistment, a woman could make her own medical decisions. A

woman who was pregnant upon entry, howev-

[240]

er, could be discharged and

denied an abortion because she did not meet one of the basic

qualifications for enlistment. That same month the Army's surgeon

general disseminated that information as guidance to hospital

commanders.61

On 3 April, however, President

Nixon abruptly changed Defense Department policies on abortion. He

directed the services to comply with the laws of the state where their

military bases were located.62

Accordingly, abortions could only be

performed as elective surgery in military hospitals in Arkansas,

California, Colorado, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Georgia,

Kansas, Maryland, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina,

and Virginia. The other states permitted abortions only when the life

or health of the mother was imperiled, and military hospitals there

were obliged to follow more stringent rules.

Abortion laws changed after

1973. That year, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that

abortion was not a crime and that the states could not restrict or

prohibit a woman's right to an abortion during her first three months

of pregnancy. The ruling put the services' abortion policy out of step

with the law of the land. After waiting for the states to change their

laws (many did so slowly, hoping the decision would be reversed), the

Department of Defense again authorized military hospitals to perform

abortions regardless of state laws, beginning in September 1975.63

Then, in November 1978, Congress banned the use of federal funds for

abortions except when pregnancy was the result of rape or incest or

when the mother's life was in danger.64

Subsequent acts continued this

prohibition.

During the 1960s, as the

director and her staff struggled with improving WAC career potential

and expanding WAC strength while maintaining standards, the situation

in Vietnam intensified. In 1964, the personnel officer at

Headquarters, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), in Saigon

wrote to the director, then Colonel Gorman, that the Republic of

Vietnam was organizing a Women's Armed Forces Corps (WAFC) and wanted

U.S. WACs to assist them in planning and developing it. The MACV

commander, then General Westmoreland, authorized

[241]

spaces for two WAC advisors.65

Before the requisitions arrived at the Pentagon, the MACV personnel

officer, Brig. Gen. Ben Sternberg, wrote Colonel Gorman, offering some

friendly advice: "The WAC officer should be a captain or major,

fully knowledgeable in all matters pertaining to the operation of a

WAC school and the training conducted therein. She should be extremely

intelligent, an extrovert and beautiful. The WAC sergeant should have

somewhat the same qualities . . . and should be able to type as

well."66

Colonel Gorman replied that the WAC would

"certainly try" to send women with "the qualifications

you outline." Then, she added, "The combination of brains

and beauty is, of course, common in the WAC."67

By the time the requisitions

arrived at the Pentagon in November 1964, the director had selected

Maj. Kathleen I. Wilkes and Sgt. 1st Cl. Betty L. Adams to fill the

positions. Both had extensive experience in WAC training, recruiting,

administration, and command. On 15 January 1965, they arrived in

Saigon and were met by Maj. Tran Cam Huong, director of the WAFC and

commandant of the WAFC training center and her assistant, Maj. Ho Thi

Ve.68

The first WAC advisors to the

Women's Armed Forces Corps set the pattern of duties for those who

replaced them every year. They advised the WAFC director and her staff

on methods of organization, inspection, and management in recruiting,

training, administering, and assigning enlisted women and officer

candidates. Time did not permit the first two WAC advisors to attend

language school before they went to Saigon, but those who followed

attended a twelve-week Vietnamese language course at the Defense

Language Institute, Monterey, California. Although Major Huong and her

key staff members spoke English, a knowledge of Vietnamese was helpful

to the WAC advisors. In 1968, an additional WAC officer advisor was

assigned to the WAFC training center located on the outskirts of

Saigon. The senior WAC advisor, then a lieutenant colonel, and the NCO

advisor, then a master sergeant, remained at WAFC headquarters in the

city and continued to help the director of the WAFC to develop

Corps-wide plans and policies. For additional training, members of the

WAFC traveled to the United States. Between 1964 and 1971, fifty-one

Vietnamese women officer candidates completed the WAC Offi-

[242]

MAJ. KATHLEEN

1. WILKES AND SGT. 1ST CL. BETTY L. ADAMS, the first WAC military

advisors in Vietnam, observe the issue of uniforms to members of the

Women's Armed Forces Corps, Republic of Vietnam, 9 March 1965.

cer Basic Course at the WAC

School; one officer completed the WAC Officer Advanced Course.69

Another group of WACs was

assigned to Saigon beginning in 1965. That year General Westmoreland

requisitioned fifteen WAC stenographers for MACV headquarters. Six

arrived by December; the balance reported in over the next few months.

Women in grades E-5 and higher with excellent stenographic skills,

maturity, and faultless records of deportment filled these positions

for the next seven years. Peak strength reached twenty-three on 30

June 1970. The senior among them acted as

[243]

NCO-in-charge and the senior

WAC advisor to the WAFC was their officer-in-charge. Initially, the

women were billeted in the Embassy Hotel, but they later moved to

other hotels in Saigon. Their minimally furnished rooms were usually

air-conditioned, and they ate in cafeterias in their hotels. Saigon,

subject to frequent terrorist attacks by the Viet Cong, was a

dangerous place to live and work. Soon after the first group arrived,

the bus that took them to work was fire-bombed, but, by luck, it was

empty at the time. The incident made walking to work attractive, but

the Viet Cong were also known to plant antipersonnel bombs in

sidewalks, steps, and doorways.70

The WAC stenographers served at

MACV headquarters and in support commands throughout the metropolitan

area. Like everyone else, they worked six-and-a-half to seven days a

week, ten to fifteen hours a day, and had little time for recreation

or socializing. Nonetheless, several extended their tours in Vietnam,

and a few returned for second and third tours of duty.71

Early in 1965, General

Westmoreland had also requisitioned a dozen WAC officers. They filled

administrative positions at MACV headquarters, in the support

commands, and in the headquarters of a new command-U.S. Army, Vietnam

(USARV), located at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, Saigon. Maj. Audrey A.

Fisher, the first to arrive, was assigned to the adjutant general's

office. Like the enlisted women, the WAC officers lived in hotels in

Saigon, walked or rode Army buses to their offices at MACV, USARV,

Headquarters Area Command, Civil Operations and Rural Development

Support Agency, 1st Logistical Command, 519th Military Intelligence

Group, and others. They worked in personnel, administration, public

information, intelligence, logistics, plans and training, and military

justice. A few WAC officers served with the U.S. Army Central Support

Command at Qui Nhon and Cam Ranh Bay.

Until 1968, WACs in Vietnam

wore the green cord uniform on duty. But, after the Tet offensive of

that year, and particularly when alerts were frequent, they wore

lightweight fatigues. During nonduty hours, they could wear civilian

clothing. In Saigon, as elsewhere in Vietnam, military personnel

converted their U.S. dollars to Military Payment Certificates, the

medium of exchange in the country. Enlisted personnel were exempt from

paying income tax on their pay while assigned to Vietnam; officers

received a $500 exemption.

Representatives of the other

women's services began arriving in Saigon in 1967. Like the WACs, they

worked at Headquarters, MACV, a joint command; at Headquarters, Naval

Forces, Vietnam; and at Head-

[244]

quarters, Seventh Air Force.

Air Force women stationed in Vietnam numbered twenty-nine officers and

twenty-two enlisted women at their peak strength in June 1971. WAVES

filled one officer position in Saigon between 1967 and 1971, but no

enlisted positions. Women Marines had a continuing complement of two

officers and nine enlisted women on duty in Saigon between 1967 and

1972.72

Approximately 5,000 Army nurses and medical specialists (men

and women) served in Vietnam between March 1962 and March 1973. Eight

nurses died there, but only one perished as a result of an enemy

attack-Lt. Sharon A. Lane.73

No other women service members died in

Vietnam.

In April 1966, the USARV

deputy commanding general, Lt. Gen. Jean E. Engler, requested that a

WAC detachment be assigned to his headquarters. He asked for 50 (later

100) clerk-typists and other administrative workers, plus a cadre

section of an officer and 5 enlisted women to administer the unit.74

Some officers in USARV opposed

the idea. They believed that the additional security required for

women would outweigh the advantages of having the WACs serve in

Vietnam. However, General Engler won over the critics when he decided

to house the WACs inside the U.S. military cantonment area at Tan Son

Nhut rather than in the city, eliminating the need for additional

guards. General Engler realized that the WACs would be exposed to

risk, but he did not consider it great enough to exclude WACs, and he

did not request that women being assigned to USARV learn to fire

weapons. However, he privately decided that if they were ever assigned

to field installations there, he would recommend that they receive

small weapons training.75

General Engler's request for a

WAC unit was approved by command channels in the Pacific area and at

the Pentagon, including the director of the WAC, and, finally, by the

chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Earle C. Wheeler.

General Engler was notified on 25 July 1966 that his request had been

approved.76

[245]

CAPT. PEGGY

E. READY, COMMANDER, WAC DETACHMENT, VIETNAM, and Lt. Gen. Jean E.

Engler, Deputy Commander, U.S. Army, Vietnam, cut the ribbon opening

the new WAC barracks area, January 1967.

The WAC cadre arrived in the

fall of 1966.77

First to arrive were 1st Sgt. Marion C. Crawford and

the administrative NCO, Sgt. 1st Cl. Betty J. Benson. The commander,

Capt. Peggy E. Ready, the supply sergeant, S.Sgt. Edith L. Efferson,

and unit clerks Pfc. Rhynell M. Stoabs and Pfc. Patricia C. Pewitt

followed. They participated in a ground-breaking ceremony on 2

November for construction of the WAC barracks. Two months later, Army

engineers completed eleven quonset huts, called hootches, for living

quarters and unit offices. On 12 January 1967, 82 enlisted women who

were to serve that first year at Headquarters, USARV, arrived. They

were welcomed by the USARV band, the press, photographers, officer and

enlisted men from the command-and the sound of mortar fire in the

distance. The first sights and sounds of Vietnam awed the women, most

of whom had little more than twelve months' service and were between

nineteen and twenty-three years old. After their arrival, the first

sergeant wrote that the WAC area became

[246]

1ST. SGT. MARION

C. CRAWFORD, WAC DETACHMENT, VIETNAM, stands retreat with the detachment,

January 1967.

alive with activity: "The

main route or shortcut to everywhere all of a sudden went right past

the WAC detachment."78

On 21 January, the detachment celebrated

its arrival by inviting 200 guests to an open house in the WAC area.

News of the party spread, and before the evening ended the WACs had

welcomed and fed over 1,800 guests.79

Six months later, along with

the entire USARV command, the detachment moved to Long Binh post,

approximately twenty-seven miles northeast of Saigon. While the

engineers readied new barracks, the women lived in a building typical

of the tropics, with openings between the outer wallboards and no

windows. Red dust covered their rooms during the dry season, and rain

soaked them during the wet season. Because of these conditions, the

USARV commander allowed the women to wear either lightweight fatigues

or the green cord uniform before that option was authorized for all

WACs in Vietnam. Most WACs chose to wear fatigues.80

Soon after the move to Long

Binh in September 1967, the director of the WAC, then Colonel

Hoisington, arrived to visit the unit. She was eager to see the women,

gauge their morale, inspect their housing, and ensure that they were

being properly used. She was accompanied by the

[247]

WAC Staff Adviser,

Headquarters, U.S. Army, Pacific, Lt. Col. Leta M. Frank. En route to

Saigon, the director had visited the WACs in Alaska, Japan, Korea, and

Okinawa; on her return trip she spent several days with the WACs at

Fort Shafter, Hawaii. Her interest in the region reflected the rapid

increase in the number of WACs serving there.

Before WACs were assigned to

Vietnam, only 44 WAC officers and 229 enlisted women were stationed in

the Pacific area-Hawaii, Japan, Korea, and Okinawa. As the war in

Vietnam intensified, however, the WAC detachment in Japan almost

doubled in size as WAC medical specialists arrived for duty in the

hospitals that received the sick and wounded from Vietnam. The

strength of the detachments in Hawaii and Okinawa remained about the

same throughout the war. A few officers and married, accompanied,

enlisted women rotated in and out of Korea, but no WAC detachment was

activated there. In January 1970, the WAC reached its peak strength in

Vietnam with 20 officers and 139 enlisted women; there were 54

officers and 393 enlisted women in the Pacific area.81

Colonel Frank

visited the WAC units annually, monitored their activities, kept the

director advised of their status, and forwarded to her a monthly

report received from each unit or contingent, complete with personnel

statistics and items of interest.82

The director spent a week in

Vietnam, conferring with General Westmoreland and the MACV deputy

commander, General Creighton W. Abrams; with members of the MACV

staff; and with commanders of subordinate activities. She talked with

the eight WAC officers and seventeen enlisted women then living in

Saigon and inspected their living and working quarters. She called on

now Col. Tran Cam Huong at Headquarters, WAFC, and toured the WAFC

training center.

Colonel Hoisington then went

to Long Binh. She conferred with Lt. Gen. Bruce Palmer and his

personnel officer, Brig. Gen. Earl F. Cole, who praised the

performance of the women and asked her advice about requisitioning

more. The director recommended that they authorize and requisition

enlisted women in higher grades. After she returned to the Pentagon

and reviewed the availability of volunteers, she wrote, "I think

we can settle on a figure between 120 and 150 if we can improve the

grade spread and add some MOS." And she added, "I don't want

to promise more than we can reasonably expect to receive in qualified

volunteers." At the time of the director's visit, the unit had 82

enlisted women with only one E-8 (the first sergeant), three E-7s, and

one E-6. By January 1970, the unit would have a strength of 139, with

45 women in grades E-8 through E-6. Although most of the women would

continue to be assigned in clerk-typist positions, the variety of MOSs

was widened

[248]

UPON ARRIVING IN VIETNAM to

inspect WAC units and personnel, Colonel Hoisington and her escort, Lt.

Col. Leta M. Frank, WAC Staff Adviser, U.S. Army, Pacific, are welcomed

by General Creighton W. Abrams, Deputy Commander, MACV, 21 September 1967.

to include specialists in

communications, personnel, finance, automatic data processing, and

intelligence.83

The enlisted women at Long

Binh greeted their director enthusiastically. Most of them had

graduated from basic training during the years when she commanded the

WAC Center and the WAC School (19641966). She visited their work

sections, talked to their supervisors, and inspected their barracks

and dining facilities. In a group session, she complimented their

excellent record of performance and discipline, passing along the

glowing praise of their supervisors, and, later, she allotted time to

individual discussions.84

On one of her last days in

Vietnam, Colonel Hoisington visited Army men at several outposts

beyond Long Binh. Traveling by helicopter in

[249]

COLONEL HOISINGTON

meets cadre members of the WAC Detachment, Vietnam, October 1967.

Left to right: Sp4c. Rhynell M. Stoabs, Sgt. 1st CL Betty J. Benson

(Acting 1st Sgt.), Colonel Hoisington, Captain Ready, SSgt. Edith L.

Efferson, and Pfc. Patricia C Pewitt.

the Army green cord uniform

(she shunned the offer of fatigues), she visited the 9th Division,

commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. O'Connor, at Camp Bearcat and talked

to men of the 4th Battalion, 39th Infantry. Lt. Gen. Frederick C.

Weyand, Commander, II Field Force, Vietnam, joined the group at noon.

From Bearcat, she went to base camps at Xuan Loc, Dinh Quan, and Gia

Ray to observe the work performed by field detachments of the Women's

Armed Forces Corps.85

Before leaving Long Binh and

later Saigon, Colonel Hoisington reported her findings to General

Palmer and General Westmoreland. In her opinion, the morale of the

WACs in Vietnam was high, their work was satisfying to them, their

commanders and supervisors were interested in their welfare, and they

were well housed, clothed, and fed. Though she preferred the women to

wear the green cord uniform to look neat and feminine, from

observation she knew this was not possible, at least until the

engineers completed the WAC barracks at Long Binh. Her trip enhanced

the morale of the women, reassured their parents, gave her

[250]

COLONEL HOISINGTON

visits with members of the WAC Detachment, Vietnam, in the unit's

courtyard at Long Binh, October 1967.

information about the unit,

and resulted in assignment of more WACs to Vietnam.86

Few problems of significance

arose during the seven years that WACs served in Vietnam; even losses

due to disease or injury were minimal. During the Tet offensive of

1968, when American casualties mounted, no WAC received a serious

injury. Many, however, did receive scrapes and bruises diving for

cover from incoming artillery fire since the ammunition depot at Long

Binh was a major target of the enemy. Captain Ready's replacement,

Captain Joanne Murphy described a scene in her orderly room:

Pay day, 31 January 1968, will

long be remembered by all of us. I had just started to pay and handed

SP5 [Delores A.] Balla her money when a deafening explosion went off

at the ammo dump. Glass, gravel and dust were flying. We couldn't see

for more than a few yards .... Meanwhile, SP5 Balla was lying in front

of my desk counting her money. A couple of times she called to SSG

Efferson [the acting first sergeant] asking if she should sign her

voucher.'No, child, just stay down,' Sergeant Efferson said.87

[251]

In February, Captain Murphy

wrote Colonel Hoisington: "We had another exciting evening on 18

February when the VC again hit our ammo dump, two very spectacular

explosions, and much more dramatic than the one on pay day. The first

blast at about 0100 hours, actually bounced some women out of their

beds .... I marvel at the calm of the women." For her part,

Colonel Hoisington was constantly concerned about their safety. She

told Captain Murphy, "That Saturday (Sunday for you) when the

news began coming through, I was worried all over again and didn't

rest well until news from there sounded more peaceful .... I'm proud

of you, Sergeant Efferson, and the rest of the women for keeping cool

heads through that period."88

A unique predicament arose

over the policy of assigning married WAC volunteers to Vietnam. As the

number of American servicemen in Vietnam grew, it was inevitable that

some would be married to WACs and that the women would do their best

to be assigned to Vietnam to be near their husbands. Unfortunately,

married WACs arriving in Saigon or Long Binh usually found that their

spouses were miles away. Even if their husbands were assigned to the

same area, no family housing existed. In either case, a morale problem

resulted. In April 1968, Lt. Col. Frances V. Chaffin, Senior WAC

Advisor, MACV, asked if anything could "be done about stopping

the assignment to Vietnam of WAC personnel whose husbands are

stationed here?" She explained that they were "causing a

problem for both the Long Binh WAC Detachment and HQ, MACV . . . .

There are just no [housing] facilities."89

Civilian wives who

had soldier husbands in Vietnam also complained to their

congressmen-married WACs could be assigned to Vietnam, but civilian

wives could not even travel there. Colonel Hoisington requested a

change in policy, and the DCSPER approved a change, effective 28 May

1969, that barred the assignment to Vietnam of married enlisted women

whose husbands were serving in Vietnam because of the nonavailability

of housing for married personnel.90

As a matter of equity, the same

policy applied to WAC officers. A few WACs evaded the policy by not

reporting their marriages.91

Few WACs left Vietnam because

of pregnancy. Of 14 married women assigned to Vietnam between 1967 and

1973, 8 were pregnant upon arrival and were promptly sent home for

discharge. Between January 1967 and September 1968, 225 single WACs

arrived in Vietnam; 5 became pregnant during their tour and went home

for discharge.92

[252]

In Vietnam, as in almost every

foreign country to which they were assigned, WACs found charitable

work to do. Soon after the detachment moved to Long Binh, the women

learned that a Catholic orphanage located at nearby Tan Heip needed

assistance. They soon adopted the orphanage, and, between 1967 and

1972, detachment personnel visited the institution weekly, providing

food and clothing as well as care and attention for the children.93

In December 1968, the WAC

detachment moved into its permanent barracks at Long Binh. The new

compound consisted of four two-story wooden buildings with cooking and

laundry facilities and a swimming pool, donated by the National WAC

Veterans Association. With housing for 130 women, the new barracks

provided ample room, and according to the detachment commander, Capt.

Nancy J. Jurgevich, was "more secure, which also makes for

privacy." She described the buildings as "new and clean. The

rooms average 20'x36', normally four or five women to a room. We have

a beautiful covered patio with a built-in stage and movie screen.

Eventually our buildings will be air conditioned."94

The strength of the WAC

detachment continued to increase. In February 1970, with 136 women

assigned, the unit was 6 over its maximum housing capacity. The

situation, however, soon changed. The withdrawal of U.S. forces from

Vietnam had begun. Within a few months, USARV could note requisition

WAC replacements to fill vacancies created by rotation. By the end of

December 1970, the WAC detachment numbered 72; by 31 December 1971,

only 46.95

In early 1972, a new WAC

director, Brig. Gen. Mildred I. C. Bailey, visited the women in

Vietnam on her tour of WAC units in the Pacific area. At the time, the

USARV WAC detachment had 35 enlisted women and was scheduled for

deactivation later in the year. General Bailey's evaluation was that

their morale and living and working conditions remained excellent.96

Two years earlier, in 1970,

the antiwar and antidraft movements had gained momentum, reaching a

crescendo when the president ordered U.S. troops into Cambodia to

destroy Viet Cong sanctuaries and supply routes. Many Americans

believed the president intended to escalate the war, and his action

was severely criticized by members of Congress, by peace groups, and

by students on college campuses from Maine to California. A student

demonstration at Kent State University brought Ohio National Guardsmen

to that campus. In the ensuing melee, guardsmen shot and

[253]

killed four students. The

incident generated mass protests and violent demonstrations at other

campuses and in cities throughout the country. The protestors

frequently burned or damaged Army recruiting offices, ROTC

installations, and federal offices. The president ended the unrest by

withdrawing more troops from Vietnam and announcing that the draft

would end on 30 June 1973.97

When a unit was deactivated in

Vietnam, the event was called a "stand down." The last

commander of the Long Binh WAC detachment, Capt. Constance C.

Seidemann, the first sergeant, 1st Sgt. Mildred E. Duncan, and the

twelve women remaining on 21 September 1972 had a stand-down party.

Captain Seidemann described the party: "We had invited 150 guests

and about 350 came . . . . We had a special three-tiered cake with

everyone's name on it, some beautiful hand-made silk flower table

decorations, and great volumes of food and two bands."98

After

the party, the women moved to Saigon and then left for the United

States. At the end of December, two WAC officers and seventeen

enlisted women remained in Saigon at Headquarters, MACV, or

subordinate commands. By the end of March 1973, all the WACs had left

Vietnam.99

WACs served successfully in

Vietnam between 1966 and 1972. Approximately 700 WACs served there;

none died there. Nor were any taken prisoner or reported missing. One

woman, Sp5c. Sheron L. Green, received the Purple Heart-the only WAC

to receive that medal since World War 11.100

Many WACs received meritorious

service awards for their contributions during the Vietnam War. Among

such awards were the Legion of Merit, Bronze Star Medal, Army

Commendation Medal, Air Medal, Meritorious Service Medal, and Joint

Service Commendation Medal. Capt. Catherine A. Brajkovich received the

Army Commendation Medal for heroism; she had alerted residents of a

bachelor officers hotel in Saigon of a fire in the building. Maj.

Gloria A. S. Olson, a journalist and photographer with the Office of

the Chief of Information, MACV, received the Air Medal for having

flown in the equivalent of 127 aerial combat missions totaling 198 air

hours during her tour in Vietnam. Maj. Sherian G. Cadoria received the

Air Medal for meritorious achievement.101

[254]

The WAC Detachment, USARV,

received unit service awards for its service in Vietnam during the

Vietnam Counter-Offensive Phase II (1 July 1966-31 May 1967) and the

Tet Offensive Campaign (30 January 1968-1 April 1968).102

In

retrospect, General Engler characterized the participation of the WACs

in Vietnam as "superb." He continued, "They handled

clerical and management assignments in headquarters Vietnam in an

outstanding manner. It would have been a serious mistake not to use

their skills. The decision to deploy the WAC's to Vietnam was

correct."103

The war in Vietnam would be the last in which women

would participate as members of a separate Women's Army Corps of the

United States Army.

In April 1971, General

Hoisington announced she would retire on 31 July of that year. The

annual brigadier general promotion board met in May and selected Col.

Mildred Inez Caroon Bailey. Secretary Resor then announced that she

would be the eighth director of the Women's Army Corps.104

Because of the standards

controversy, General Hoisington left the directorship with ambivalent

feelings about her tour. Many positive events had occurred: the

promotion of twelve WAC officers to full colonel and one to brigadier

general; the attendance of WAC officers at the senior service

colleges; initiation of the WAC Student Officer Program; establishment

of a WAC NCO Leadership Course, and a WAC Personnel Specialists Course

at WAC School. WAC strength had expanded from 9,958 in 1966 to 12,781

in 1971.105

A WAC unit had served successfully in Vietnam. Discharge

on marriage was reinstated. A fundraising drive had been initiated to

build a WAC Museum. The WAC Journal had begun quarterly publication.

General Hoisington, however,

was sorely disturbed by the Army's decision to grant waivers for

enlistment, appointment, and retention on duty in cases of pregnancy,

parenthood, and other disqualifications. To her, such changes signaled

the beginning of the end-the disintegration of the high standards the

Corps had upheld since 1942. In the closing days of her tour, she said

to her staff, "I would trade the stars today to recover what we

have lost this year."106

[255]

GENERAL HOISINGTON

shares a moment at her retirement review at WAC Center, Fort McClellan,

with her mother, Mrs. Gregory Hoisington, 30 July 1971.

The director set aside her

personal disappointment and completed her last few months in office

with typical energy and diligence. She oriented General Bailey and

participated in farewell parties and ceremonies for her retirement. On

Friday, 30 July, she went to Fort McClellan for a formal retreat

ceremony followed by a reception and dinner party at the Officers

Club. The next morning, a retirement review was held in her honor at

the Marshall Parade Ground. Army Chief of Staff Westmoreland attended

the ceremony and presented her with the Distinguished Service Medal

the

third WAC to receive it. In his remarks, General Westmoreland said:

"Elizabeth Hoisington's associates in the Army will long remember

her as the zealous guardian of the standards of the Women's Army

Corps. In her we found our modern-day Pallas Athene and, like Pallas

Athene, she is renowned and respected for her courage and

wisdom."107

[256]