| Author: | Greene, Evarts Boutell |

| Title: | Provincial America, 1690-1740. |

| Citation: | New York, N.Y.: Harper and Brothers, 1905 |

| Subdivision: | Front Matter |

| HTML by Dinsmore Documentation * Added February 3, 2003 |

|

ix

PROVINCIAL AMERICA x

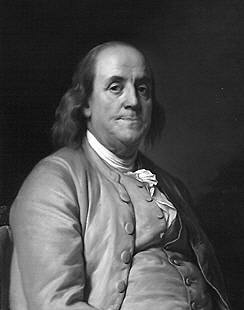

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN From the painting by Duplessis, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; painted for the Vicomte De Buissy, and presented to the Museum in 1895 by George A. Lucas xi PROVINCIAL AMERICA 1690-1740 Evarts Boutell Greene, Ph.D. New York

xii Copyright 1905 by Harper & Brothers. xiii CONTENTS

MAPS

xv EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION TO the period between 1689 and 1740 has been applied the term “The Forgotten Half-Century.” Most of the writers on colonial history in detail give special attention to the seventeenth century, the period of upbuilding; and the general historians like Bancroft and Hildreth sweep rather lightly over the epoch between the English Revolution and the forerunnings of the American Revolution. In distributing the parts of The American Nation, this period has been selected for especial treatment, because within it are to be found the roots of many later institutions and experiences. The external side of provincial history, especially in its relations with France, has been reserved for Thwaites’s France in America (vol. VII. of this series), except so far as it affected the internal development of the colonies previous to 1713. Space is thus available for a constitutional treatment which shall bring out the general imperial system of Great Britain, the organs and methods of colonial control, and the principles of domestic government in America; and to put the subject in a proper relation with the economic and social life of the time. xvi The book begins with an account of imperial conditions in 1689 (chap. i); the next four chapters are devoted to various phases of colonial government, and bring into relief the disposition of the English authorities to tighten the reins of colonial control. The establishment of the English Church in some of the colonies and the attempt to bring the colonies into the English “system,” ecclesiastically as well as politically, is the theme of chapter vi. Chapters vii. to x. summarize the military struggle in the colonies brought on by the world rivalry between France and England; but this war is treated in its relations with American colonial history, leaving out the extensions of Canada and Louisiana beyond the reach of the colonists, and also avoiding the European side of the story. Chapters xi. to xiii. develop the changes in imperial and local government during the first third of the eighteenth century, and also deal with the important subject of the beginnings of political organization in America. Chapters xiv. to xviii. are devoted to the social and economic development of the Continental colonies, including the movement of new masses and new race elements across the ocean; the filling-in of the settled area; and the pushing backward to the mountains, and southward to the southern boundary, of the new colony of Georgia. Special stress is laid upon the extension of the Navigation Acts to xvii the West India and to over-sea trade, thus supplementing the treatment of that subject in Andrews’s Colonial Self-Government (vol. V., chap. i.). Within the last chapter of text the author deals with the intellectual and literary life of the people. The Critical Essay on Authorities ranges in order the most valuable part of the confusing literature of the period. The service of the book to the series is to build a bridge between the founding of the colonies, described in the fourth and fifth volumes of The American Nation, and the separation of the colonies, which is the subject of Howard’s Preliminaries of the Revolution (vol. VIII.). Its theme is the essential difficulty of reconciling imperial control with the degree of local responsibility which had to be accorded to the colonists. xix AUTHOR’S PREFACE THE half-century of American history which follows the English revolution of 1689 presents peculiar difficulties of treatment. The historian must deal with the experience of thirteen different colonies which were, however, ultimately to become one nation, and which even then possessed important elements of unity. Within the limits of a single volume it is obviously impossible to tell the story of each individual colony, and at the same time to discuss the general movements of the time. It is the author’s conviction that the most instructive method for the student of this period is to emphasize the general movements. The history of this provincial era is comparatively deficient in dramatic incidents; and the interest lies rather in the aggregate of small transactions, constituting what are called general tendencies, which gradually and obscurely prepare the way for the more striking but not necessarily more important periods of decisive conflict and revolution. First of all, this was a time of marked expansion the seventeenth century stocks were reinforced by large numbers of immigrants; the areas of settlement xx were extended; and there was also an important development of industry and commerce. This material expansion led up gradually to the struggle for the mastery of the continent, which will be described in the next volume. A second important feature of the time is the interaction of imperial and provincial interests. After the violent and radical movements of the years from 1684 to 1689, there was worked out for the first time a fairly complete system of imperial control. In the efforts of the colonists to preserve within that system the largest possible measure of self-government, principles were involved which were brought to more radical issues in the revolu tionary era. In the political conflicts of this period such men as Thomas Hutchinson and Benjamin Franklin were trained for the larger posts assigned to them in later years. Finally, with all due allowance for divisive forces, there was a growing unity in provincial life. Material expansion was gradually filling the wilderness spaces which divided the colonies; a broader, though still provincial, culture was increasing the points of intellectual contact; under various forms of government, the Americans of that time cherished common ideals of personal liberty and local autonomy. Scholars generally agree that the subject-matter of this volume has never been adequately treated as a whole, though there are some good monographs and an almost bewildering mass of local and xxi antiquarian publications. It is hardly possible even now to write a history which can be called in any sense definitive; certainly, no such claim is made for the present work. In the main, the author’s purpose has been to state fairly, and to correlate, conclusions already familiar to special students in this field. Mr. David M. Matteson prepared the preliminary sketches for the maps in this volume. The author desires also to express his more than usual obligations to the editor for helpful suggestions both as to matter and form. EVARTS BOUTELL GREENE. xxii xxiii PROVINCIAL AMERICA

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dinsmore Documentation presents Classics of American Colonial History